Monobloc and bipartition advancement by external distraction plays a major role in the treatment of syndromic craniosynostosis. They can reverse the associated facial deformity and play a role in the management of ocular exposure, intracranial hypertension, and upper airway obstruction. Facial bipartition distraction corrects the intrinsic facial deformities of Apert syndrome. Both procedures are associated with relatively high complication rates principally related to ascending infection and persistent cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Modern perioperative management has resulted in a significant decline in complications. External distractors allow fine tuning of distraction vectors and improve outcome but are less well tolerated than internal distractors.

Key points

- •

Monobloc and bipartition advancement by external distraction plays a major role in the treatment of syndromic craniosynostosis. Bipartition distraction was developed to address the midfacial deformities of Apert syndrome.

- •

These techniques can reverse the deformity associated with syndromic craniosynostosis and mitigate complications associated with ocular exposure, intracranial hypertension, and upper airway obstruction.

- •

The procedure is associated with relatively high complication rates principally related to ascending infection and persistent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks. Distraction protocols should be used to mitigate risks of CSF leak, infection, and relapse.

- •

Distraction allows greater stable advancements than conventional osteotomies.

- •

External distractors allow fine tuning of distraction vectors and improve outcome but are less well tolerated that internal distractors.

Introduction

The monobloc osteotomy effectively cleaves the entire midfacial skeleton from the skull base and mobilizes the forehead, allowing these segments of bone to be advanced in relation to the rest of the skull. It is particularly useful in treating many types of syndromic craniosynostosis. The monobloc enlarges orbital and intracranial volume, increases the size of the nasopharynx, and corrects deformity thus producing functional and aesthetic benefits. Facial bipartition is a modification of the monobloc osteotomy that cleaves the face into 2 segments through a midline osteotomy. Its main indication is to treat hypertelorism, but the bipartition also enables a differentially greater advancement of the midface, which has greatly improved the treatment of Apert syndrome.

Monobloc advancement remains a major operation with a relatively high complication rate. A monobloc osteotomy includes both a transcranial and a transfacial procedure and thus creates a potential connection between the nasopharynx and intracranial cavity. Unless great care is taken to repair this connection, there is significant risk of ascending infection and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak.

The advent of distraction has made frontofacial advancement both safer by reducing the risk of ascending infection and more predictable by allowing in treatment adjustments to the degree and vector of advancement. Both internal and external distractors are used, each with their pros and cons. Internal distractors are more convenient for the patient and allow prolonged fixation in the consolidation period but is difficult to adjust distraction vectors and distractor removal requires a second operation. External distractors are more cumbersome but allow fine tuning the distraction advancement.

History of external distraction and frontofacial advancement

Distraction osteogenesis, the technique of bone lengthening by gradual tensile stress across a bone gap, was first described in the early 1900s. Initially implemented in orthopedic surgery by Illizarov in lower extremity reconstruction, its application has since been broadened to include distraction of the craniofacial skeleton.

External craniofacial distraction was first reported by Synder (1973) in a canine mandibular model. The technique entered general clinical use after McCarthy published his experience with mandibular distraction in 4 children. In these early reports, distraction was performed using external distractors anchored into the bone using 4 screw half-pins. The external fixator remained in place for 8 to 10 weeks postdistraction without reported complications.

Internal devices were soon developed in an attempt to provide greater stability, decreased facial scarring, and less cumbersome hardware leading to greater patient comfort. Initially used in the mandible by Diner in 1996 these devices have been developed for use in the midface and other parts of the craniofacial skeleton. Over the past 3 decades, however, numerous advances have refined skeletal advancement techniques. Its utilization in the craniofacial skeleton has increased significantly, with most centers performing some form of craniofacial distraction.

Frontofacial advancement has been enhanced significantly by the implementation of external distraction osteogenesis. , The initial description of monobloc advancement by Ortiz Monasterio in 1978 and the modification to include facial bipartition by van der Meulen resulted in midface correction but with a high complication rate. , , These techniques were built on the early techniques of Gillies and Tessier. , Facial bipartition allows for the correction of the central concavity that is seen in Apert syndrome and represents an early attempt to both advance the midface and correct intrinsic bony deformities. , Because of the high morbidity and risk, this procedure was initially performed in only limited centers, but with the advent of craniofacial distraction, these transcranial frontofacial advancements have been performed more widely with reduced morbidity.

Indications

The precise indications for craniofacial distraction remain controversial. , Frontofacial advancement by distraction may be indicated in syndromic craniosynostosis to correct deformity or treat functional problems including the following:

- •

Intracranial hypertension by correcting craniocerebral disproportion

- •

Exorbitism by enlarging the orbits

- •

Airway, speech, and feeding difficulties by advancing the midface

Frontofacial advancement can be used to treat any of these functional problems, but there are often simpler less extensive alternatives. In view of the magnitude of the procedure, it is commonly used only where there is a combination of functional problems or where an individual problem is so severe that there is no other realistic alternative.

Frontofacial distraction may be performed at any age from early infancy to adulthood, and the indications vary with age with a focus on function in the young and deformity in older patients ( Fig. 1 ). Monobloc advancement in infancy is challenging. The fragility and pliability of the infant skull make stable advancements problematic particularly in the central part of the midface. External distraction provides stable fixation with central pull, which differentially advances the midface producing a better correction of deformity and greater enlargement of the airway. Internal distractors by contrast push laterally to move the midface and thus bend the face unfavourably. Monobloc is favored over bipartition in the very young, as the midline osteotomy of the bipartition increases instability. Monobloc advancement in very young children is indicated where there is vision-threatening exorbitism characterized by globe subluxation and exposure keratopathy and in cases of severe midface retrusion with airway compromise and raised intracranial pressure.

Timing of surgery

The timing for frontofacial advancement is determined by the functional and aesthetic goals of the procedure. For an infant with recurrent globe subluxation and severe midface hypoplasia, the frontofacial advancement can be performed at a young age (see Fig. 1 ).

Some surgeons feel that young children do not tolerate the consolidation period when wearing an external device. The experience at Great Ormond Street Hospital is that young children adapt and cope very well with the external, halo-type frame. An increasing number of units are performing frontofacial distraction at a younger age. ,

Some centers do limit the use of frontofacial advancement to later childhood and teenage years. The rationale is that there is an increased rate of relapse and requirement for secondary midface advancement when performed in children younger than 9 years. , Anterior midfacial growth is arrested after advancement, and with ongoing mandibular growth there is a risk for mandibulo-maxillary disproportion. Undertaking surgery toward the end of facial growth reduces this risk and overcorrection of midface advancement is recommended in the growing child. Disadvantages of later surgery include the fact that bone regeneration is more complete at a younger age and that complication rates increase with age. The authors’ current philosophy on timing is as follows:

- •

Surgery for functional reasons when indicated at any age

- •

To correct severe deformity

- •

Surgery at 8 to 12 years when upper midfacial growth is almost complete

- •

Accept that Le Fort I or bimaxillary osteotomy may be needed at 18 years

Surgical planning and choice of procedure

Midfacial advancement may be achieved using transcranial procedures (monobloc, bipartition) or subcranial procedures (Le Fort II with zygomatic osteotomies, Le Fort III). Advancement may be obtained either conventionally, using bone grafts, or by distraction. The best form of correction will achieve the maximum functional anesthetic gains with the fewest complications and minimum inconvenience to the patient and family. To achieve these aims, static procedures (midface advancement with or without bone graft) are preferred to distraction and subcranial procedures to transcranial operations.

The limitations of static and subcranial procedures often make them unsuitable for the treatment of severe midfacial retrusion. It is difficult to achieve stable advancements greater than 1 cm with conventional advancement, and harmonious correction of the orbits and forehead often mandates transcranial corrections.

All children undergoing frontofacial advancement, whether subcranial or dura exposing, should undergo a computed tomography (CT) scan preoperatively. The predicted amount of advancement required at the orbital level determines whether advancement is performed in a static fashion using bone graft or using distraction osteogenesis. Any patient requiring more than 10 mm of advancement will undergo advancement via distraction. Distraction is also indicated in the very young where facial bones are too pliable to achieve stable fixation. It is also useful to allow fine tuning of the endpoint of advancement.

Operative technique

A summary of the authors’ approach to frontofacial advancement by distraction is as follows:

Positioning

- •

Supine

- •

Head ring and a shoulder roll is placed to ensure mild neck extension to prevent compression of neck veins

- •

he head of bed facilitates venous drainage

Setup

- •

Circummandibular wire to secure the armoured endotracheal tube

- •

Temporary tarsorrhaphies to protect the corneas

- •

The nares and oral cavity washed with betadine

- •

Intraoperative cell salvage to reduce blood product donor exposure

- •

Tranexamic acid is given at the start of each case

Exposure

- •

Bicoronal incision and upper buccal sulcus incision

- •

kin is incised using monopolar cautery and raised in a subgaleal plane

- •

An anteriorly based pericranial flap is preserved and used later in the anterior cranial fossa floor reconstruction

- •

The coronal flap is taken down to expose the nasal bones, entire orbit, and zygomatic arch. It is our preference to leave the medial canthi attached to prevent postoperative telecanthus. With the soft tissue protected, a reciprocating saw is used to complete the osteotomy cuts. A detailed technical summary of the techniques is presented elsewhere.

An alternative to the coronal incision has been proposed by Maercks and colleagues. They have described a minimal access technique of monobloc osteotomy. They used an ultrasonic scalpel and endoscope to perform the osteotomies while minimizing soft tissue dissection.

Midface Osteotomies and Disimpaction

- •

Monobloc osteotomies are undertaken in the following order:

- ○

Division of zygomatic arch

- ○

Circumorbital osteotomies

- ○

Completion of anterior skull base cut across the midline

- ○

Pterygomaxillary osteotomy

- ○

Separation of nasal septum from skull base

- ○

- •

Our preference is to perform the pterygomaxillary disjunction from an intraoral approach, which gives better control and reduces the risk of significant hemorrhage.

- •

The monobloc osteotomy is then mobilized.

- •

A facial bipartition may now be completed if indicated by removing a midline wedge of bone superiorly and dividing the hard palate and maxillary alveolus in the midline. The bipartition fragments are then mobilized and fixed with a titanium plate placed in the glabella region.

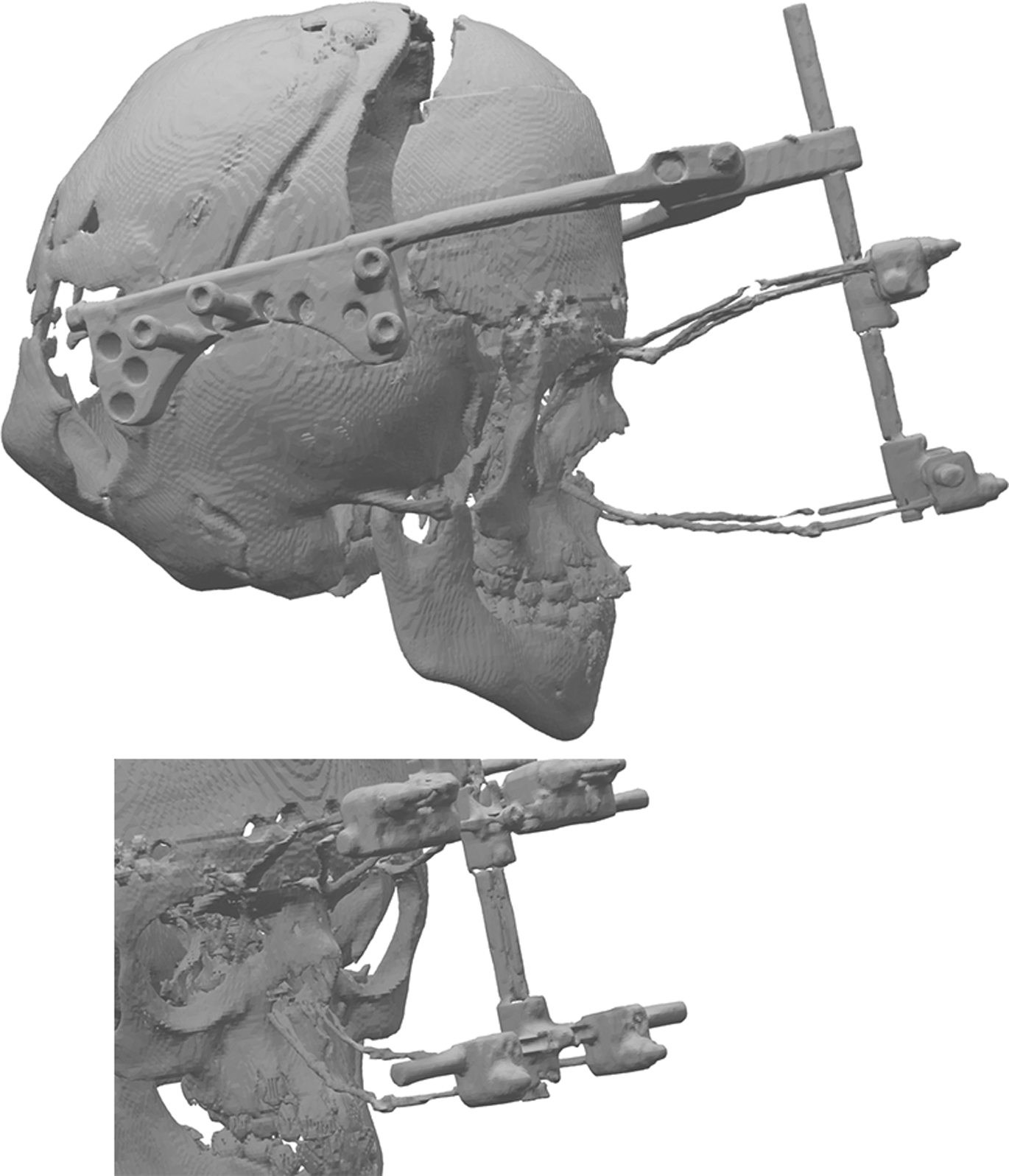

Attachments for the distractor wire are now placed using a combination of drill holes and titanium plates. Our preference is generally to place 3 fixation points above the orbit positioned in the midline and just lateral to the supraorbital notch. Fixation at the lower maxillary level is through drill holes in the inferior lateral part of the piriform aperture ( Fig. 2 ). Many clinicians prefer the use of a fixation to the upper dental arch using a splint, which is an effective method, but, in our experience, the pyriform aperture wires are more comfortable for the patient.