The seventh version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Melanoma Staging guidelines, published in 2009, has significant revisions compared with the previous version. The current schema was based on the largest melanoma patient cohort analyzed to date and is the result of a multivariate analysis of 30,946 patients with stages I, II, and III melanoma and 7972 patients with stage IV melanoma. This article summarizes the findings and the new definitions included in the 2009 AJCC Melanoma Staging and Classification. The TNM categories and the stage groupings are defined. Changes in the melanoma staging system are summarized.

- •

Dermal primary melanoma mitogenicity is considered one of the 3 most powerful prognostic factors, along with ulceration and tumor thickness, in patients with localized melanoma.

- •

Tumor thickness remains the primary determinant of T staging and should be measured using the method described by Breslow.

- •

Dermal mitotic figures are counted using the hot spot method and are reported as the number of mitoses per squared millimeter.

- •

Ulceration is reported in the primary melanoma only if there is absence of epidermis with an underlying inflammatory infiltrate and traumatic ulceration has been ruled out.

- •

The presence of a single melanoma cell in a sentinel lymph node, visualized by hematoxylin-eosin stain or by one of the melanocytic markers, upstages the patient to IIIb.

- •

The most powerful predictors of survival in patients with regional disease are the number of lymph nodes affected, metastatic tumor burden, ulceration, and thickness of the primary tumor.

This article summarizes the findings and the new definitions included in the 2009 AJCC Melanoma Staging and Classification. The TNM categories for this seventh edition of the AJCC Staging Manual are defined in Table 1 , and the stage groupings are defined in Table 2 . Changes in the melanoma staging system are summarized in Table 3 .

| T | Thickness (mm) | Ulceration Status and Mitoses |

|---|---|---|

| T is | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| T1 | ≤1.00 | T1a: without ulceration and mitoses <1/mm 2 T1b: with ulceration or mitoses ≥1/mm 2 |

| T2 | 1.01–2.00 | T2a: without ulceration T2b: with ulceration |

| T3 | 2.01–4.00 | T3a: without ulceration T3b: with ulceration |

| T4 | ≥4.01 | T4a: without ulceration T4b: with ulceration |

| N | No. of Metastatic Nodes | Nodal Metastatic Burden |

|---|---|---|

| N0 | 0 | Not applicable |

| N1 | 1 | N1a: micrometastasis a N1b: macrometastasis b |

| N2 | 2–3 | N2a: micrometastasis a N2b: macrometastasis b N2c: in transit metastases/satellites without metastatic nodes |

| N3 | 4+ metastatic nodes, or matted nodes, or in transit metastases/satellites with metastatic nodes |

| M | Site | Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase |

|---|---|---|

| M0 | No distant metastases | Not applicable |

| M1a | Distant skin, subcutaneous, or nodal metastases | Normal |

| M1b | Lung metastases | Normal |

| M1c | All other visceral metastases | Normal |

| Any distant metastasis | Increased |

a Micrometastases are diagnosed after sentinel lymph node biopsy.

b Macrometastases are defined as clinically detectable nodal metastases confirmed pathologically.

| Clinical Staging a | Pathologic Staging b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | N | M | T | N | M | ||

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| IA | T1a | N0 | M0 | IA | T1a | N0 | M0 |

| IB | T1b T2a | N0 N0 | M0 M0 | IB | T1b T2a | N0 N0 | M0 M0 |

| IIA | T2b T3a | N0 N0 | M0 M0 | IIA | T2b T3a | N0 N0 | M0 M0 |

| IIB | T3b T4a | N0 N0 | M0 M0 | IIB | T3b T4a | N0 N0 | M0 M0 |

| IIC | T4b | N0 | M0 | IIC | T4b | N0 | M0 |

| III | Any T | N >N0 | M0 | IIIA IIIB IIIC | T1-4a T1-4a T1-4b T1-4b T1-4a T1-4a T1-4a T1-4b T1-4b T1-4b Any T | N1a N2a N1a N2a N1b N2b N2c N1b N2b N2c N3 | M0 M0 M0 M0 M0 M0 M0 M0 M0 M0 M0 |

| IV | Any T | Any N | M1 | IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

a Clinical staging includes microstaging of the primary melanoma and clinical/radiologic evaluation for metastases. By convention, it should be used after complete excision of the primary melanoma with clinical assessment for regional and distant metastases.

b Pathologic staging includes microstaging of the primary melanoma and pathologic information about the regional lymph nodes after partial (ie, sentinel node biopsy) or complete lymphadenectomy. Pathologic stage 0 or stage IA patients are the exception; they do not require pathologic evaluation of their lymph nodes.

| Factor | Sixth Edition Criteria | Seventh Edition Criteria | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness | Primary determinant of T staging | Same | Thresholds of 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mm |

| Level of invasion | Used only for defining T1 melanomas | Same | Used as a default criterion only if mitotic rate cannot be determined |

| Ulceration | Included as a secondary determinant of T and N staging | Same | Signifies a locally advanced lesion; dominant prognostic factor for grouping stages I, II, and III |

| Mitotic rate per mm 2 | Not used | Used for categorizing T1 melanoma | Mitosis ≥1/mm 2 used as a primary criterion for defining T1b melanoma |

| Satellite metastases | In N category | Same | Merged with in transit lesions |

| Immunohistochemical detection of nodal metastases | Not included | Included | Must include at least 1 melanoma-associated marker (eg, HMB-45, Melan-A, MART-1) unless diagnostic cellular morphology is present |

| 0.2 mm threshold of defined N+ | Implied | No lower threshold of staging N+ disease | Isolated tumor cells or tumor deposits <0.1 mm meeting the criteria for histologic or immunohistochemical detection of melanoma should be scored as N+ |

| Number of nodal metastases | Primary determinant of N staging | Same | Thresholds of 1 vs 2–3 vs 4+ nodes |

| Metastatic volume | Included as a second determinant of N staging | Same | Clinically occult (microscopic) nodes are diagnosed at sentinel node biopsy vs clinically apparent (macroscopic) nodes diagnosed by palpation or imaging studies, or by the finding of gross (not microscopic) extracapsular extension in a clinically occult node |

| Lung metastases | Separate category as M1b | Same | Has a better prognosis than other visceral metastases |

| Increased serum LDH level | Included as a second determinant of M staging | Same | Recommend a second confirmatory LDH level if increased |

| Clinical vs pathologic staging | Sentinel node results incorporated into definition of pathologic staging | Same | Large variability in outcome between clinical and pathologic staging; sentinel node staging encouraged for standard patient care, should be required before entry into clinical trials |

Localized melanoma: stages I and II

Mechanics of Primary Melanoma Staging

For patients with T1 cutaneous melanoma (primary tumor thickness <1.0 mm), thickness, mitotic count, and ulceration of the primary tumor are the most powerful predictors of survival.

Primary tumor thickness

The staging thresholds of melanoma thickness are unchanged from the sixth edition of the AJCC. A cutaneous melanoma staged as T1 is 1.0 mm thick or less. T2 includes tumors from 1.01 to 2.0 mm thick. T3 measures from 2.01 to 4.0 mm, and a T4 lesion is more than 4.0 mm thick. Because primary tumor thickness is the most powerful predictor of melanoma survival, it remains the cornerstone for patient management. It is therefore a critical component of the pathology report and it must be determined with accuracy. The objective measurement of tumor thickness, as originally described by Breslow, requires the use of an intraocular micrometer. A calibration table should be used to ensure accurate measurement across different brands and models of microscopes. The measurement is taken from the top of the granular cell layer to the deepest invasive melanoma cell. When ulceration is present, the measurement is taken from the base of the ulcer to the deepest point of tumor cell invasion. Deep tumoral cells along perineural and periadnexal (adventitial) dermis, as well as perivascular or intravascular extension, are not included in the primary tumor thickness measurement. When the primary tumor has a polypoidal architecture, the Breslow thickness is obtained by measuring across the largest diameter of the lesion perpendicular to the skin surface.

Mitotic count

One of the most important changes in the revised staging system is the introduction of mitotic count as a criterion for category T1. The mitotic count, expressed as number of dermal mitoses/mm 2 (n/mm 2 ), represents a strong and independent prognostic factor in this patient subset. The conclusion of various statistical analyses was that the most significant correlation with survival was at a threshold of 1/mm 2 or more. A highly significant correlation between increasing mitotic count and declining survival rates has also been shown. The identification of mitoses as an important independent predictor of survival in patients with thin primary tumors led to the inclusion of dermal mitotic activity of the primary tumor as a new component of the seventh edition of the melanoma staging system. For the staging system to be uniformly and universally applied, it is critical that the assessment and reporting of the pathologic variables are consistent. Because the studies that revealed mitoses as clinically significant were retrospective studies that used the hot spot technique of evaluating tumor mitogenicity, the AJCC Melanoma Staging Committee recommends that mitotic count be determined by this approach and reported as the number of mitoses per square millimeter of the primary tumor. This measurement is accomplished by examination of routine hematoxylin-eosin–stained tissue sections of the most representative profile of the tumor. It is not necessary to perform exhaustive tissue sectioning. Once the area with the most mitotic figures (hot spot) has been identified, the count starts using a standard 10× ocular and a high power objective (40×). After determining the number of mitoses in the first high power field, the count is extended to adjacent fields until an area of 1 mm 2 is assessed. To ensure accuracy across observers, individual microscopes must be calibrated to determine the number of high power fields (400×) that correspond to 1 mm 2 . The most common microscopes are sized such that 1 mm 2 equals approximately 4 high power fields. The final mitotic count must be reported as n/mm 2 . If only 1 mitosis is found, this should be reported as 1/mm 2 . If no dermal mitoses are identified, the count should be reported as 0/mm 2 . In cases in which dermal mitotic figures are uniformly distributed or scarce, and do not aggregate in a hot spot, the count starts with a randomly selected mitotic figure and proceeds to adjacent fields, as outlined earlier. When the invasive component of the tumor measures less than 1 mm 2 the count should be performed on all of the dermal tumor and reported as n/mm 2 . In small biopsies, one can also encounter partial sampling of the invasive component amounting to less than 1 mm 2 ; in these cases, the AJCC recommends that the count be recorded as at least n/mm 2 . Alternatively, when the invasive tumoral compartment is extensive, encompassing several square millimeters, if only 1 mitotic figure is found, the count is reported as 1/mm 2 . The AJCC Melanoma Staging Committee strongly discourages the use of <1/mm 2 in reporting melanoma. It is important to distinguish between the reporting function, which should always be in a whole number/mm 2 , and the staging language, which is described as a range (eg, greater than or equal to 1/mm 2 ).

With regards to special stains, the detection of Ki-67 in more than 20% of dermal melanoma cells is associated with an increased risk of lymph node metastasis in patients with thin, less than 1 mm, primary melanoma. If this test is performed on primary cutaneous melanomas, it is recommended that it is reported as the percentage of dermal tumor cells staining, using a threshold of 20%. Another immunohistochemical stain that holds promise is antiphosphohistone H3 (anti-PHH3). By highlighting mitotic figures at any stage of mitosis, this is a highly sensitive detection method. Additional studies that identify appropriate quantitative thresholds for reporting the results of anti-PHH3 are needed before its use in routine reporting of primary melanoma. The current recommendation is to examine a limited number of hematoxylin-eosin–stained tissue sections and to report the number of mitoses identified in 1 mm of tumor based on the hot spot technique.

Ulceration

The presence of ulceration in the primary tumor was described as a highly significant poor prognostic indicator as early as 1953. However, it came to occupy its rightful place in the TNM classification and melanoma staging only after the thorough review that led to the sixth edition of the AJCC melanoma staging system. Similar to tumor thickness, the current edition is unchanged with regards to ulceration. The presence of ulceration upgrades the corresponding T classification from Ta to Tb. For T1 melanomas, ulceration is used along with the presence or absence of dermal mitoses. A T1 melanoma without ulceration and with no dermal mitoses is designated as T1a. However, the presence of ulceration alone is enough to upgrade a thin melanoma from T1a to T1b, regardless of the mitogenicity of the tumor. Ulceration is defined as full-thickness interruption of the epidermis by tumor without previous history of mechanical trauma or surgery at the site. This finding must be accompanied by reactive changes (ie, fibrin deposition, granulation tissue, and mixed inflammatory infiltrate).

Other Important Factors not in the Schema

Clark level

In the sixth edition of the AJCC staging system, the anatomic level of invasion as described by Wallace Clark was discontinued as the primary determinant of T staging; nevertheless, this parameter was still used to stratify patients with a Breslow thickness of less than 1 mm. However, the latest results showed that the level of invasion is no longer statistically significant when mitotic count and ulceration are included in the analysis. Hence, the new recommendation is that the mitotic count be used as the primary criterion for considering a melanoma as T1b. The level of invasion is used only when the mitotic count cannot be reliably determined because of poor preparation of the histology slides. For example, on rare occasions, the histologic sections are too thick or overstained and mitotic figures cannot be distinguished in a dark cellular background. In such cases, the level of Clark can be used in place of the mitotic count, as described in the sixth edition.

Regression

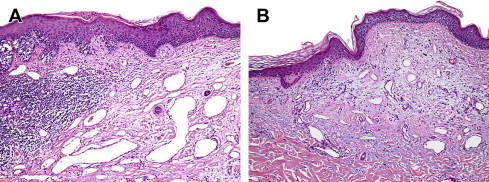

The phenomenon of regression was described by Clark and colleagues as an important prognostic indicator and it has been associated with increased likelihood of metastasis, even in thin melanomas. Regression is defined as the focal absence of tumor within or immediately adjacent to an otherwise viable melanoma. The regressed area is characterized by complete absence of melanoma cells in the epidermis and dermis, flanked on one or both sides by viable melanoma cells. Histologically this area can show a thin epidermis with underlying fibroplasia, increased vascularity, chronic inflammation, and melanophages ( Fig. 1 ). When the criteria described earlier are strictly applied the presence of regression is indeed an important prognostic indicator. However, in many instances, there is an overcall of regression in primary melanomas and this is one of the main reasons why this phenomenon has not yet been validated in larger patient cohorts. Several secondary changes are commonly misinterpreted as regression, such as the presence of fibrosis, chronic inflammation, or melanophages in a background of viable melanoma cells, as well as the presence of focal reactive fibrosis as a result of trauma. As mentioned earlier, all these reactive changes are part of regression, but only when accompanied by a complete lack of viable tumor cells in the relevant area.