Juvenile Hypertrophy

Dennis C. Hammond

Eric Yu Kit Li

ANATOMY

At thelarche, the breast develops into glandular tissue composed of lobules and ducts and supporting stromal tissue.

Breast development continues until the age of 18 to 20, at which point growth is complete.

The arterial supply of the breast is derived from numerous sources, including perforators from the internal thoracic, external thoracic, thoracoacromial, and anterior and posterior branches of intercostal arteries.

The internal thoracic artery is the dominant source.

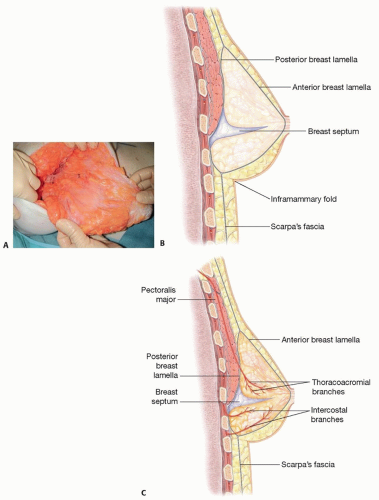

The blood supply to the nipple-areolar complex (NAC), in particular, is augmented by a rich vascular arcade that travels in a distinct fascial septum known as Wuringer septum3 (FIG 1A).

The arcade takes origin from the thoracoacromial, external thoracic, and intercostal arteries.

The septum arises approximately at the level of the 5th rib, dividing the breast into a superior two-thirds and inferior one-third, and courses from the pectoralis major fascia to the NAC (FIG 1B,C).

Preservation of the septum and its vascular arcade is key to maintaining a robust NAC during pedicle dissection in breast surgery.

The venous drainage of the breast parallels the arterial supply.

The lymphatic drainage of the breast is generally to the axillary and internal mammary lymph nodes.

A variety of sensory nerves innervate the breast, including the anterior and lateral branches of the 2nd through 6th intercostal nerves and supraclavicular nerves.

The NAC is predominantly innervated by the lateral branch of the 4th intercostal nerve.

The breast is enveloped by the Scarpa fascia, which forms anterior and posterior lamellae.

Cooper ligaments are intraparenchymal fibers, which span both lamellae and confer structural support to the breast.

The inframammary fold (IMF) is the foundation of the breast and is the point of convergence of the Scarpa fascia of the abdomen inferiorly with the anterior and posterior lamellae of the breast superiorly.4

The fat layer above the Scarpa fascia is thicker, denser, and more compact than the fat layer below it.

Avoidance of downward deforming pressures on the subscarpal fatty layer/space, whether by an implant or parenchyma, is key to preventing “bottoming out” of the breast and undesired lowering of the IMF.

PATHOGENESIS

Theories include either increased end-organ sensitivity to normal levels of gonadal hormones or increased levels of gonadal hormones, although previous studies have identified normal hormone levels in juveniles diagnosed with this disease.

NATURAL HISTORY

Juvenile hypertrophy is characterized by rapid and atypical breast growth during puberty.

Initial growth over the first 6 months may be extreme, followed by a longer period of slower growth.

Disease onset can be anytime during puberty, but in most cases, it is shortly after thelarche (ages 9 to 13).

Involvement can be either unilateral, which is more common, or bilateral.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Juveniles with the suspected diagnosis should be evaluated for both signs and symptoms related to rapid breast growth.

A detailed history should inquire about:

The onset and velocity of breast growth

The onset of puberty and ongoing pubertal development

Associated symptoms, including headaches; neck, shoulder, or back pain; shoulder grooving from brassiere straps; and skin irritation or intertrigo along the IMF

Any social, vocational, or avocational dysfunction due to the hypertrophied breasts

The effect of the breasts on the patient’s psychological well-being and self-esteem

Any personal or family history of breast cancer or disorders

A detailed physical should examine

The patient’s height, weight, and body mass index

For signs related to hypertrophied breasts, including skin striae or hyperemia, peau d’orange skin, dilated subcutaneous veins, or, in severe cases, tissue necrosis involving the breast

For specific masses, irregularities, or deformities involving the breasts or chest wall

Overall breast aesthetics, including the shape and size of the breasts and NACs, the degree of ptosis, and the position and symmetry of the IMFs

Standard breast measurements to highlight asymmetries, including the sternal notch to nipple, midclavicular to nipple, nipple to midline, and nipple to IMF distances

IMAGING

Mammography tends to be of limited value because of the density of the breast tissues in juvenile hypertrophy.

Ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in select situations, especially if masses or irregularities are identified on examination and the diagnosis is in question.

Ultimately, diagnosis of juvenile hypertrophy is often clinical and based on history and examination.2

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS5

Physiologic breast hypertrophy (including normal growth or pregnancy-related growth)

Benign breast tumors (eg, fibroadenoma, giant fibroadenoma, phyllodes tumor, or cysts)

Malignant breast tumors (eg, ductal or lobular carcinoma, lymphoma, or metastases)

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Pharmacologic therapies, including tamoxifen, dydrogesterone, danazol, and bromocriptine, have been used as both primary treatment options or in combination with surgery, in either a neoadjuvant or adjuvant fashion.6

The safety and efficacy of these therapies are not well established, however, due to the scarcity of reported cases.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical treatment of juvenile hypertrophy is reduction mammoplasty.

Surgery is ideally performed once breast size has stabilized for 6 to 12 months, but earlier intervention may be necessary if there are overriding functional, medical, or psychosocial concerns.2,7

All resected breast tissues should be sent for histopathological examination to rule out breast pathologies.

Reduction mammoplasties are completed using the short scar periareolar inferior pedicle (SPAIR) technique.8,9

The SPAIR technique is advantageous over other techniques for numerous reasons:

It is versatile and can be used for breast reductions of varying size.

Most plastic surgeons have been trained and are comfortable using the inferior pedicle.

The circumvertical skin resection pattern minimizes scar burden, creates a more rounded breast shape, and improves breast projection while avoiding wound healing difficulties at the T junction or vertical segments associated with other breast reduction techniques.

Lessening the scar burden is a significant priority in young female patients.

The breast can be actively shaped with various intraoperative maneuvers to achieve the final desired contour.

The IMF is preserved, thus minimizing the risk of long-term “bottoming out” of the breast.

Preoperative Planning

The patient should be seen preoperatively 1 to 3 days before surgery to achieve several objectives:

To review the procedure in detail and revisit goals and expectations of surgery with the patient

To complete all perioperative paperwork, including orders, prescriptions, and instruction sheets

To mark the patient in an unrushed, quiet, and controlled environment

To obtain preoperative photographs of the marked patient

Preoperative markings can be done with a variety of colored markers, each representing a specific surgical step.

The patient is marked in a standing position with arms at the sides.

A laser leveler can be used to confirm the horizontal plane across the chest.

The midsternal line, IMF, lateral breast contour, and breast meridian are first marked (FIG 2A).

The IMF is drawn across the chest so that it can be visualized with the breasts at rest (FIG 2B).

The periareolar pattern is outlined next:

The top point is the intersection of a line 2 to 4 cm above the IMF with the breast meridian (FIG 2C).

The bottom points are the top points of a rectangle, which is drawn 8 cm wide, centered on the breast meridian and arising from the IMF, with a height of 8 to 10 cm (FIG 2D).

The lateral and medial points are identified by lifting the breast up and outward and up and inward with just enough tension to create a rounded contour and transposing the breast meridian onto the breast (FIG 2E,F).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree