CHAPTER 74 Hyaluronic acid injectable filler

History

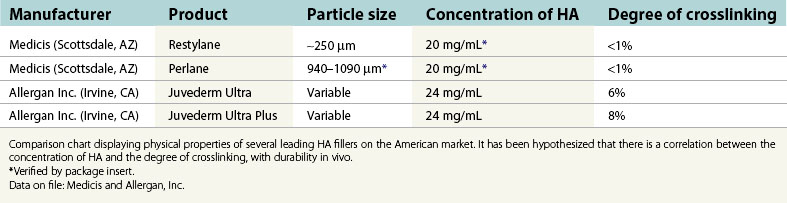

In 1996, non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) was placed on the European market under the trade name Restylane and was well received due to its increased longevity over collagen fillers. In a randomized study reported in 2003, Restylane was compared to Zyplast (bovine collagen; Inamed Aesthetics, Inc. Santa Barbara, CA.). The study indicated “superiority” of Restylane over Zyplast employing the Wrinkle Severity Rating Scale (WSRS) “at all time points and at 6 months” (Narins et al., 2003). This research also demonstrated a comparable safety profile and was instrumental for FDA approval within the United States later that year. According to a statistical analysis by the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, there were 1,593,554 HA injection procedures performed in the United States during 2006, making it the second most popular cosmetic procedure within our specialty. Currently, both NASHA as well as animal-derived HA are marketed by multiple sources throughout the world. Individual products vary in regard to particle size, concentration of HA as well as the degree of cross-linking. These attributes correlate with the product’s corrective abilities, flow characteristics, and, presumably, duration (Table 74.1).

Physical evaluation

• Possible contraindication to treatment such as uncontrolled bleeding disorders, history of keloids, relevant allergies, etc.

• The use of NSAIDs and certain herbal products may create increased bruising, and should be avoided if at all feasible.

• What are the patient’s goals and expectations?

• What are the patient’s limitations in terms of “down time”

• Can this be achieved by means of a hyaluronic acid (HA) based filler?

• Type and depth of defect (determines product placement).

• Size of defect (determines volume of product).

• Anesthesia requirements – topical, infiltration, and/or nerve block.

Anatomy

Facial aging is commonly characterized by the loss of cutaneous and subcutaneous volume. This is attributable to resorption of the facial skeleton and atrophy of subcutaneous fat. In addition, there is thinning of the dermis with pronounced elastosis and a progressive reduction of HA. These factors combine to produce the aesthetically recognizable stigmata of the aged face, such as sagging and wrinkling of the skin, as well as increased prominence of the bony landmarks and vascular structures (Fig. 74.1).

Traditionally, these anatomical changes were most commonly corrected via exclusively surgical modalities (e.g. rhytidectomy), and we truly believe the surgical facelift remains the gold standard for addressing lax and aged skin of the face. More recently, however, a “synergistic” approach addressing skin laxity and excess, as well as the loss of volume is becoming favorable. It is within this philosophy of volumetric restoration that HA fillers have found a well-defined niche. In addition, injectable therapies offer a treatment option for patients who are not candidates for, or are unwilling to undergo elective aesthetic surgery.

Technical steps

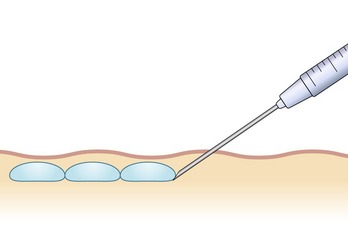

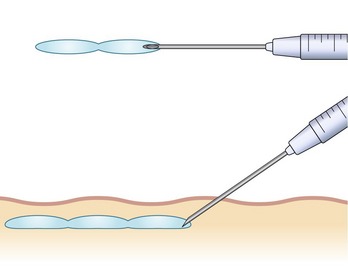

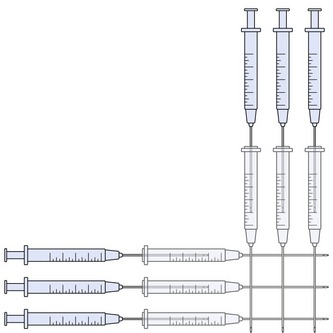

There are numerous techniques that can be used for injection of HA products. These methods vary depending upon the area being addressed, as well as the preferences of the injector. Most commonly, “serial puncture” or a “linear threading” technique are employed, especially when treating the nasolabial folds, specific rhytides or the lip border. By fully inserting the needle and injecting while it is being withdrawn, as in threading, we have the added benefit of fewer puncture sites. We often combine both methods in a “serial threading” approach, which also requires less injection points, yet allows precise placement of the filler product (Figs 74.2, 74.3). By always keeping the needle moving during injection, a smooth and predictable deposition of product is achieved.

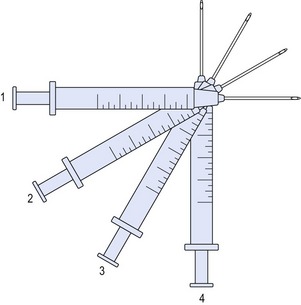

For larger flat areas such as the malar prominence or cheek, a “fanning” pattern of injection is often beneficial. As in threading, the needle is inserted fully, and the filler is extruded upon withdrawal. Prior to removal from the injection site, the trajectory is redirected in a radial pattern and repeated, not unlike the cannula movements in a suction lipectomy procedure. This configuration may be overlaid at 90 degrees, in a variation of the “cross-hatch” technique, providing volumization in a uniform manner (Figs 74.4, 74.5).

The most commonly treated areas for soft tissue augmentation with HA are the nasolabial folds, which is currently the only site specifically approved and labeled for injection by the FDA. This is also a reasonable area for the novice injector to gain experience in the use of HA fillers, as it is fairly forgiving. Correction is typically achieved with 1–3 mL injected bilaterally, depending upon severity. Often, there is a asymmetry in these folds, which must be addressed in the treatment plan in order to optimize results. Overcorrection, however, is discouraged, as it may produce an unnatural appearance which is accentuated with muscular contraction. It is of key importance that the product be placed in the deep dermis to avoid being visible and is injected slightly inferomedial to the folds themselves to prevent exacerbation of the deformity. An overlaid fanning technique works well in the superior aspects for this application, where the most volume is generally required (Figs 74.6–74.9).

Figs 74.6 & 74.7 Plan for injection of tear troughs, bilateral inframalar hollows and nasolabial folds in a 38-year-old woman who complains of volume deficiency of her face.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree