Coxa saltans is a term popularized by Allen and various co-authors.1

Encompasses three types

• Internal type (iliopsoas tendon)

• External type (iliotibial band)

• Intra-articular type was originally attributed to diverse intra-articular pathology (ie, loose bodies, labral tears, etc.).

Today, there is more accuracy in the description and diagnosis of intra-articular hip pathology, therefore it is no longer referred to as snapping hip.

Today, there is more accuracy in the description and diagnosis of intra-articular hip pathology, therefore it is no longer referred to as snapping hip.

ANATOMY

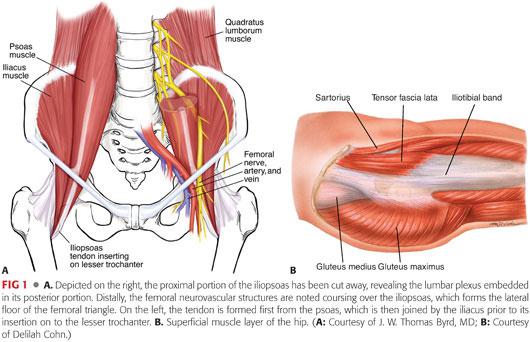

The iliopsoas complex, a powerful hip flexor, is formed from the psoas major and iliacus muscles (FIG 1A).

The iliopsoas complex, a powerful hip flexor, is formed from the psoas major and iliacus muscles (FIG 1A).

The psoas major originates from the lumbar transverse processes and the lateral surfaces of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs from T12 to L5; the iliacus originates from the superior two-thirds of the iliac fossa, the sacral ala, and the anterior sacroiliac ligaments.

The tendon forms first from the psoas proximal to the inguinal ligament and then rotates such that its anterior surface comes to lie medial and its posterior surface lateral.

The tendon broadly inserts over the lesser trochanter.

It is joined by an accessory tendon from the iliacus, and the tendons then fuse together before forming the enthesis of the iliopsoas. Some muscle fibers of the iliacus remain separate, attaching directly to bone.

In the sagittal plane, as the iliopsoas exits the pelvis, it is redirected 40 to 45 degrees over the pectineal eminence toward its insertion site.

The iliotibial band and its associated muscles act to flex, abduct, and internally rotate the hip (FIG 1B): The fascia lata covers the entire hip region, encasing its three superficial muscles, that is, the tensor fascia lata, sartorius, and gluteus maximus.

The iliotibial band and its associated muscles act to flex, abduct, and internally rotate the hip (FIG 1B): The fascia lata covers the entire hip region, encasing its three superficial muscles, that is, the tensor fascia lata, sartorius, and gluteus maximus.

A confluence of the tensor fascia lata and gluteus maximus forms the iliotibial band.

A confluence of the tensor fascia lata and gluteus maximus forms the iliotibial band.

The gluteus maximus also partly inserts into the proximal femur at the gluteal tuberosity.

This fibromuscular sheath was described by Henry12 as the “pelvic deltoid,” reflecting on the fashion in which it covers the hip, much as the deltoid muscle covers the shoulder.

PATHOGENESIS

Internal Type

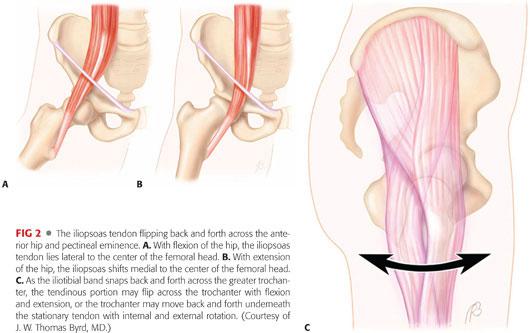

The snapping occurs as the iliopsoas tendon subluxes from lateral to medial while the hip is brought from a flexed, abducted, and externally rotated position into extension with internal rotation (FIG 2A,B).

The snapping occurs as the iliopsoas tendon subluxes from lateral to medial while the hip is brought from a flexed, abducted, and externally rotated position into extension with internal rotation (FIG 2A,B).

It has been theorized that the anterior aspect of the femoral head and capsule, the pectineal eminence, the iliopsoas bursa, or some combination of these are responsible for transiently impeding the tendon and creating the snapping.

Incidental, asymptomatic snapping of the iliopsoas tendon is estimated to be present in at least 10% of a normal, active population.5

Painful snapping may be precipitated by macrotrauma or repetitive microtrauma in patients with a predilection for certain activities such as ballet.

The exact structural alteration that occurs when symptomatic snapping develops has not been defined.

External Type

The external snapping hip originates as the iliotibial band snaps over the prominence of the greater trochanter and often is attributed to a thickening of the posterior part of the iliotibial band or anterior border of the gluteus medius (FIG 2C).

The external snapping hip originates as the iliotibial band snaps over the prominence of the greater trochanter and often is attributed to a thickening of the posterior part of the iliotibial band or anterior border of the gluteus medius (FIG 2C).

The thickened portion lies posterior to the posterior edge of the greater trochanter in extension and slides and snaps into an anterior position as the hip begins to flex.

The greater trochanteric bursa lies between the iliotibial band and greater trochanter. It overlies the tendinous insertion of gluteus medius and vastus lateralis origin. In some instances, it may become inflamed and painful secondary to snapping.

Coxa vara and reduced bi-iliac width have been proposed as predisposing anatomic factors.

Tightness of the iliotibial band also may be an exacerbating factor.

Like snapping of the iliopsoas tendon, snapping of the iliotibial band may be an incidental finding without precipitating cause or symptoms.

Painful snapping may occur following trauma but is more commonly associated with repetitive activities, classically being described in the downhill leg of runners training on a sloped roadside surface.

It also has been reported as an iatrogenic process following surgical procedures that leave the greater trochanter more prominent, or reconstructive procedures around the knee that alter the iliotibial band.

NATURAL HISTORY

For most people, the snapping hip remains asymptomatic, never requiring treatment.

For most people, the snapping hip remains asymptomatic, never requiring treatment.

In patients in whom the snapping hip is symptomatic, the course is variable, but there are no apparent long-term consequences of a chronic snapping hip.

In patients in whom the snapping hip is symptomatic, the course is variable, but there are no apparent long-term consequences of a chronic snapping hip.

Spontaneous resolution may occur but is uncommon.

Spontaneous resolution may occur but is uncommon.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Iliopsoas Tendon

The history of onset of symptoms is variable and may be insidious, owing to specific repetitive maneuvers or an acute injury.

The history of onset of symptoms is variable and may be insidious, owing to specific repetitive maneuvers or an acute injury.

Symptomatic internal coxa saltans presents with anterior groin pain and associated snapping, which is often audible.

Patients often report snapping with climbing stairs or rising from a chair.

Although the symptoms typically are referred to the anterior groin, some patients may describe flank or sacroiliac discomfort, reflecting irritation around the origin of the psoas and iliacus muscles.

Physical examination is performed with the patient supine, hip flexed greater than 90 degrees, abducted and externally rotated, then passively brought into extension with internal rotation; this recreates the snap.

In some instances, this is a dynamic process that the patient can demonstrate actively better than the examiner can elicit on physical examination. Although often prominent, it may be subtle and may occur more as a sensation experienced by the patient rather than one that the examiner can observe objectively.

Applying pressure over the anterior joint can block the tendon from snapping and assist in confirming the diagnosis.

Iliotibial Band

As with the iliopsoas tendon, patients may describe the onset of symptoms as being insidious due to specific repetitive activities or in response to acute trauma.

As with the iliopsoas tendon, patients may describe the onset of symptoms as being insidious due to specific repetitive activities or in response to acute trauma.

Whereas snapping of the iliopsoas tendon often can be heard from across the room, snapping of the iliotibial band can be seen from across the room.

Clinical presentation is typical in two forms:

• The “hip dislocator,” characterized by the patient asserting the ability to dislocate the hip without a correlating pain elicitation. This action is typically reproducible by the patient on bilateral weight bearing while tilting and rotating the pelvis with lateral displacement of the affected side.

• This pseudosubluxation/pseudodislocation gives the visual appearance of the hip displacing, but radiographs uniformly demonstrate that the hip remains concentrically reduced.

• “True” external snapping hip is characterized by snapping phenomenon at the greater trochanteric region with hip flexion and extension.

The patient nearly always relates a snapping or subluxation-type sensation. The symptoms are located laterally, and patients typically can illustrate this while standing.

As with the iliopsoas, this often is a dynamic process, better demonstrated by the patient than produced by passive examination. It may be detected with the patient lying on the side and then passively flexing and extending the hip.

The snap can be palpated over the greater trochanter, and its origin is confirmed by applying pressure, which can block the snap from occurring.

The Ober test evaluates for tightness of the iliotibial band, which may accompany symptomatic snapping.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The diagnosis of a both external and internal snapping hip is based primarily on history and physical examination, and investigative studies offer little aid in substantiating or discounting the diagnosis.

The diagnosis of a both external and internal snapping hip is based primarily on history and physical examination, and investigative studies offer little aid in substantiating or discounting the diagnosis.

Nonetheless, plain radiographs remain an essential tool in the assessment of any hip problem.

Nonetheless, plain radiographs remain an essential tool in the assessment of any hip problem.

Plain radiographs consist of an anteroposterior (AP) pelvis, AP hip, and lateral radiographs. Although these films are usually normal, some cases may show evidence of cam femoroacetabular impingement.

Plain radiographs consist of an anteroposterior (AP) pelvis, AP hip, and lateral radiographs. Although these films are usually normal, some cases may show evidence of cam femoroacetabular impingement.

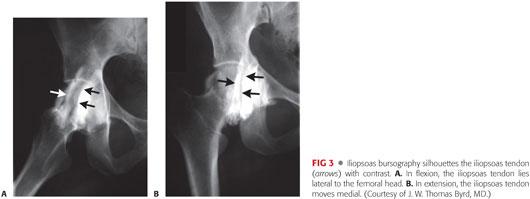

Iliopsoas bursography and fluoroscopy may dynamically document the phenomenon and be helpful to rule in, but not rule out, the diagnosis (FIG 3).

Iliopsoas bursography and fluoroscopy may dynamically document the phenomenon and be helpful to rule in, but not rule out, the diagnosis (FIG 3).

Ultrasonography of the iliopsoas is a dynamic noninvasive study that may document snapping phenomenon as well as pathologic changes of the iliopsoas tendon and its bursa.

Ultrasonography of the iliopsoas is a dynamic noninvasive study that may document snapping phenomenon as well as pathologic changes of the iliopsoas tendon and its bursa.

The limiting factor with these dynamic imaging modalities is the technical proficiency of the test provider and their experience and ability to reproduce the snapping while examining hip motion.

With consideration that almost half of patients with internal snapping hip syndrome have associated intra-articular pathology,4,10,15 magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) may be performed to demonstrate any intra-articular pathology and report changes related to the iliopsoas tendon or bursa.

With consideration that almost half of patients with internal snapping hip syndrome have associated intra-articular pathology,4,10,15 magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) may be performed to demonstrate any intra-articular pathology and report changes related to the iliopsoas tendon or bursa.

An image-guided intra-articular injection of lidocaine or cortisone can have significant benefit in distinguishing between extra and intra-articular hip pathology.

An image-guided intra-articular injection of lidocaine or cortisone can have significant benefit in distinguishing between extra and intra-articular hip pathology.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Snapping iliotibial band

Snapping iliotibial band

Hip instability

Hip instability

Snapping iliopsoas tendon

Snapping iliopsoas tendon

Intra-articular pathology

Intra-articular pathology

Pelvic instability (eg, sacroiliac joint or symphysis pubis)

Pelvic instability (eg, sacroiliac joint or symphysis pubis)

Osteochondroma

Osteochondroma

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Treatment often involves little more than establishing the diagnosis and assuring the patient that the snapping is not harmful or indicative of future problems.

Treatment often involves little more than establishing the diagnosis and assuring the patient that the snapping is not harmful or indicative of future problems.

Oral anti-inflammatory medications may be helpful in addition to a flexibility and stabilization exercise program.

Oral anti-inflammatory medications may be helpful in addition to a flexibility and stabilization exercise program.

For recalcitrant cases

For recalcitrant cases

A period of activity modification to diminish symptoms may be necessary.

Judicious use of corticosteroid injections may be appropriate, with the goal of providing transient improvement to supplement the effect of other therapeutic modalities.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Iliopsoas Tendon

Traditionally, open surgical procedures have been described for releasing or lengthening the tendinous portion of the iliopsoas, with generally favorable results.1,7,11,19

Traditionally, open surgical procedures have been described for releasing or lengthening the tendinous portion of the iliopsoas, with generally favorable results.1,7,11,19

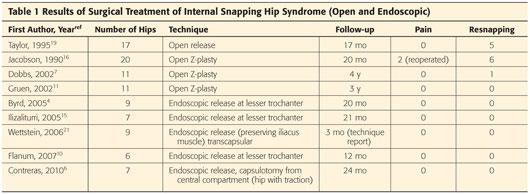

Recently, successful endoscopic release has been reported and compares well with the results reported for open release or open lengthening techniques (Table 1).

Recently, successful endoscopic release has been reported and compares well with the results reported for open release or open lengthening techniques (Table 1).

Studies have demonstrated that nearly half of the patients with internal snapping hip syndrome have associated intra-articular pathology.4,10,15

Studies have demonstrated that nearly half of the patients with internal snapping hip syndrome have associated intra-articular pathology.4,10,15

Failure to inspect the interior of the hip joint and address associated pathology may be a significant contributing factor to less optimal results with traditional open techniques.

Failure to inspect the interior of the hip joint and address associated pathology may be a significant contributing factor to less optimal results with traditional open techniques.

Iliotibial Band

Various techniques have been described for correcting snapping of the iliotibial band.

Various techniques have been described for correcting snapping of the iliotibial band.

One complex procedure is a Z-plasty lengthening, the results of which have ranged from poor to good.2,17,18

One complex procedure is a Z-plasty lengthening, the results of which have ranged from poor to good.2,17,18

Several techniques have employed a simpler approach, creating a relaxing incision in the portion of the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter, and these have shown to be effective at eliminating the snapping in most cases.5,22 Violation of the tendon structure is minimized, which diminishes the morbidity of the procedure and facilitates the postoperative recovery.

Several techniques have employed a simpler approach, creating a relaxing incision in the portion of the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter, and these have shown to be effective at eliminating the snapping in most cases.5,22 Violation of the tendon structure is minimized, which diminishes the morbidity of the procedure and facilitates the postoperative recovery.

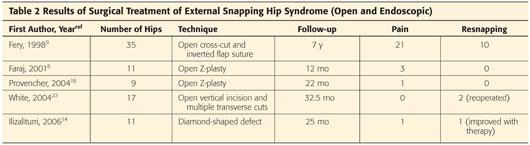

Endoscopic methods have been developed that may accomplish this same goal, comparing well with open techniques (Table 2).

Endoscopic methods have been developed that may accomplish this same goal, comparing well with open techniques (Table 2).

Preoperative Planning

Clinical assessment of the snapping iliopsoas tendon and iliotibial band is relatively straightforward.

Clinical assessment of the snapping iliopsoas tendon and iliotibial band is relatively straightforward.

However, careful assessment is necessary to ensure that the snapping is clearly the source of the patient’s symptoms and also to evaluate other associated conditions, especially concomitant intra-articular pathology.

However, careful assessment is necessary to ensure that the snapping is clearly the source of the patient’s symptoms and also to evaluate other associated conditions, especially concomitant intra-articular pathology.

Perhaps, most important is a careful assessment of the patient’s motivation, understanding, and goals of recovery.

Perhaps, most important is a careful assessment of the patient’s motivation, understanding, and goals of recovery.

It is important to bear in mind that coxa saltans often is encountered in asymptomatic individuals.

It is important to bear in mind that coxa saltans often is encountered in asymptomatic individuals.

Surgery is considered only if the patient has exhausted efforts at conservative treatment and demonstrates sufficient motivation for the postoperative recovery.

Surgery is considered only if the patient has exhausted efforts at conservative treatment and demonstrates sufficient motivation for the postoperative recovery.

Positioning

Iliopsoas tendon

Iliopsoas tendon

Endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon is performed in conjunction with routine arthroscopy of the joint.

Arthroscopy can be performed with the patient in either the supine or lateral position, with each having their advantages.

Iliotibial band

Iliotibial band

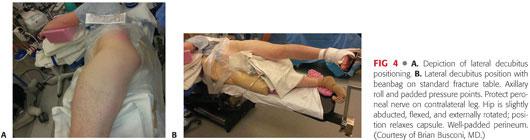

Open procedures employ the lateral decubitus position, and this also has been the preferred orientation for endoscopic methods (FIG 4).

Approach

Iliopsoas tendon

Iliopsoas tendon

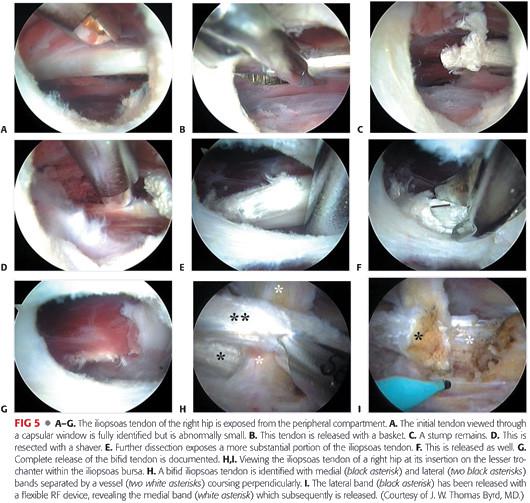

Most endoscopic reports have described releasing the tendon from its insertion on the lesser trochanter within the iliopsoas bursa.3,15

This is the endoscopic counterpart to the open method described by Taylor and Clarke.19 For the occasional case of a snapping iliopsoas tendon associated with a total hip arthroplasty, it clearly is the preferred approach.

Another endoscopic technique, in which the iliopsoas tendon is approached from the peripheral compartment, seems to provide a comparable effect of releasing the tendon.15 The method is analogous to the open method described by Allen et al.1 Theoretically, it may have an advantage of reduced morbidity and can be performed without traction.

Endoscopic release of the iliopsoas at the central compartment has been recently reported and demonstrated excellent results.6 This technique is performed while viewing with a 70-degree arthroscope under traction.

Iliotibial band

Iliotibial band

The various open approaches use a common, lateral, longitudinal incision over the greater trochanter.

Endoscopic methods employ laterally based portals, approaching the tendon from its superficial subcutaneous surface.

TECHNIQUES

Endoscopic Iliopsoas Release

Endoscopic Iliopsoas Release

Lesser Trochanter (Iliopsoas Bursa)

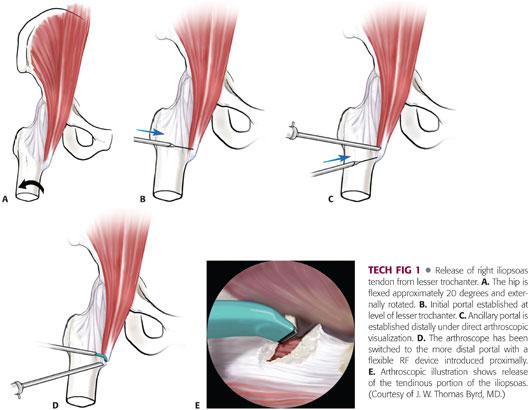

After completing routine hip arthroscopy, including intra-articular and peripheral compartments, traction is removed and the leg is repositioned in 20 degrees of flexion and full external rotation.

Slight flexion partially relaxes the tendon but maintains some tension.

External rotation brings the lesser trochanter more anterior for access from the laterally based portals (TECH FIG 1A).

A portal is established distal to the standard anterolateral hip portal at the level of the lesser trochanter using fluoroscopic guidance (TECH FIG 1B).

This exposes the tendon within the iliopsoas bursa, which is the largest bursa in the body.

Another portal is then placed distally, converging toward the lesser trochanter (TECH FIG 1C).

The arthroscope and instruments are switched between these two portals for thorough visualization and instrumentation of the iliopsoas tendon (TECH FIG 1D).

Adhesions within the bursa can be cleared, providing excellent visualization of the iliopsoas tendon.

The tendinous portion of the iliopsoas is transected adjacent to its insertion on the lesser trochanter (TECH FIG 1E).

This is facilitated with the use of a flexible radiofrequency (RF) device.

For safest technique, the medial side of the tendon is fully visualized, and the tendon is then released from medial to lateral. Its fibers will separate 1 to 2 cm.

Muscular attachments of the iliacus muscle are preserved.

Peripheral Compartment

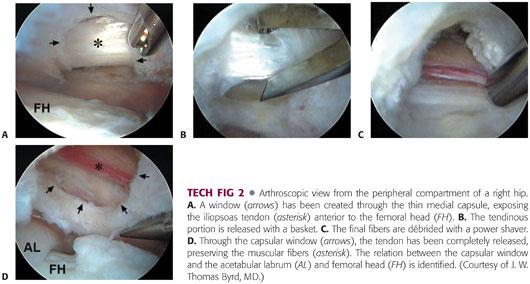

After completing arthroscopy of the intra-articular compartment, traction is released, hip is flexed to 45 degrees, and standard portals are established in the peripheral compartment (TECH FIG 2).

An anterior hip capsulotomy is performed between the labrum and zona orbicularis, establishing a communication between the capsule and the iliopsoas bursa.

The iliopsoas tendon is identified at this level and released via a thermal device, hand biter, or power shaver, being sure to leave the iliacus muscle intact just beyond the tendon.

The muscular portion separates the tendon from the femoral nerve, which is the most lateral of the femoral neurovascular structures.

Central Compartment

This technique is performed under traction with a 70-degree arthroscope.

A capsulotomy is performed anteriorly between the anterior labrum and anterior femoral head at the 2 to 3 o’clock position of the labrum, via the direct anterior portal.

The iliopsoas tendon is exposed through this capsulotomy and released at that level while the fibers of the iliacus are preserved.

Tendoplasty of the Iliotibial Band

Tendoplasty of the Iliotibial Band

Open Technique

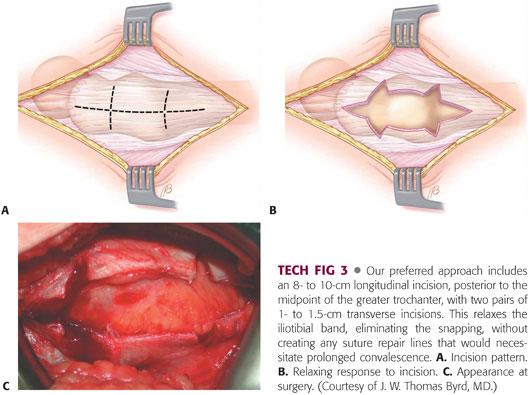

A straight, lateral longitudinal incision is centered over the greater trochanter (TECH FIG 3).

The length is dictated by the amount of exposure needed to precisely accomplish the tendoplasty.

A smaller incision is more cosmetic and can be accomplished with dissection of the subcutaneous tissues and selective retraction but should not compromise visualization for the procedure.

Several authors have described variations of a similar method for relaxing the tendon. These are based on an 8- to 10-cm longitudinal incision just posterior to the mid part of the greater trochanter in the thickest portion of the iliotibial band.

Relaxation of the tendon is completed with paired or staggered 1- to 1.5-cm transverse incisions.

The field is relatively bloodless, but meticulous hemostasis should be maintained and the subcutaneous tissues closed in layers to avoid formation of a hematoma.

Endoscopic Technique

With the patient in lateral decubitus, care is taken to drape the patient to allow for free range of motion of the extremity; this is to ensure snapping phenomenon can be recreated intraoperatively.

Traction is not required.

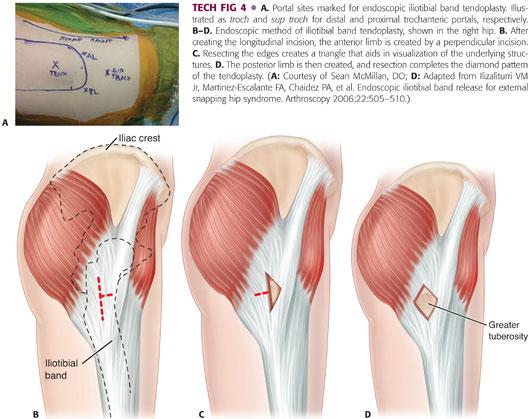

Two portals are used: one just proximal to the tip of the greater trochanter and one distal to the greater trochanter, with area of snapping between both portals (TECH FIG 4A).

The space under the iliotibial band can then be infiltrated with 40 to 50 mL of saline.

The distal trochanteric portal is established with standard arthroscopic cannula introduced subcutaneously and directed proximally toward proximal trochanteric portal, using the blunt obturator to establish a working space above the iliotibial band.

Then, with arthroscopic visualization, the proximal portal is established for dissection to release the subcutaneous tissue from the superficial surface of the tendon, maintaining careful hemostasis throughout (TECH FIG 4B–D).

A 4- to 5-cm longitudinal retrograde incision within the tendon is created using a shaver and/or an RF probe, beginning at the level of the distal viewing portal.

An anteriorly based 2-cm transverse incision is then made at midpoint of vertical cut and the flaps resected, creating a long, obtuse triangle.

This provides better visualization to determine the relation of the iliotibial band and the underlying greater trochanter.

Lastly, a posterior transverse incision is made at the same level as the anterior incision and the flaps excised, creating a diamond-shaped pattern of resection.

This release is most important and performed until snapping has ceased.

The greater trochanteric bursa can be removed through the defect and abductor tendons inspected for tears.

A compressive dressing is applied to minimize the formation of a hematoma.

PEARLS AND PITFALLS | |

Visualization |

|

Violation of iliopsoas tendon |

|

Failure to fully release tendon |

|

Inadequate tendoplasty |

|

Proper diagnosis |

|

| |

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

After these procedures, the patient is capable of full weight bearing, but crutches are used for about 2 weeks until the gait pattern is normalized.

After these procedures, the patient is capable of full weight bearing, but crutches are used for about 2 weeks until the gait pattern is normalized.

Gentle range-of-motion, closed-chain, and stabilization exercises are introduced as symptoms allow.

Gentle range-of-motion, closed-chain, and stabilization exercises are introduced as symptoms allow.

For iliopsoas release, aggressive hip flexion strengthening is avoided for the first 6 weeks; for the iliotibial band, aggressive stretching generally is not necessary.

For iliopsoas release, aggressive hip flexion strengthening is avoided for the first 6 weeks; for the iliotibial band, aggressive stretching generally is not necessary.

The patient should not anticipate returning to vigorous activities for at least 3 months.

The patient should not anticipate returning to vigorous activities for at least 3 months.

OUTCOMES

For endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon, several studies have reported highly predictable results in terms of eliminating the snapping and patient satisfaction.3,13

For endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon, several studies have reported highly predictable results in terms of eliminating the snapping and patient satisfaction.3,13

Heterotopic ossification has been observed following arthroscopic release of the iliopsoas from the lesser trochanter.13

Heterotopic ossification has been observed following arthroscopic release of the iliopsoas from the lesser trochanter.13

These observations are consistent with reports in the literature on open techniques of the iliopsoas tendon that have noted a propensity for heterotopic bone formation.18

These observations are consistent with reports in the literature on open techniques of the iliopsoas tendon that have noted a propensity for heterotopic bone formation.18

For snapping of the iliotibial band, tendon-relaxing procedures that maintain the structural integrity of the abductor mechanism, whether performed open or endoscopically, have predictably corrected the snapping with minimal morbidity.5,9,20

For snapping of the iliotibial band, tendon-relaxing procedures that maintain the structural integrity of the abductor mechanism, whether performed open or endoscopically, have predictably corrected the snapping with minimal morbidity.5,9,20

COMPLICATIONS

No reports have been published of complications with endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon.

No reports have been published of complications with endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon.

Cases of heterotopic ossification have been observed, for which Ilizaliturri has recommended pharmacologic prophylaxis.13

Cases of heterotopic ossification have been observed, for which Ilizaliturri has recommended pharmacologic prophylaxis.13

Potential complication due to damage to surrounding structures (eg, femoral neurovascular bundle)

Potential complication due to damage to surrounding structures (eg, femoral neurovascular bundle)

No complications have been reported in conjunction with the less extensive tendon-relaxing procedures for a snapping iliotibial band. Careful attention to the precision of the release can help avoid inadequate or excessive tendoplasty. Inadequate release could result in residual symptoms, whereas excessive release could result in a virtually unsalvageable compromise of the abductor mechanism.

No complications have been reported in conjunction with the less extensive tendon-relaxing procedures for a snapping iliotibial band. Careful attention to the precision of the release can help avoid inadequate or excessive tendoplasty. Inadequate release could result in residual symptoms, whereas excessive release could result in a virtually unsalvageable compromise of the abductor mechanism.

REFERENCES

1. Allen WC, Cope R. Coxa saltans: the snapping hip revisited. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1995;3:303–308.

2. Brignall CG, Stainsby GD. The snapping hip, treatment by Z-plasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991;73B:253–254.

3. Byrd JWT. Evaluation and management of the snapping iliopsoas tendon. Instr Course Lect 2006;55:347–355.

4. Byrd JWT. Evaluation and management of the snapping iliopsoas tendon. Tech Orthop 2005;20:45–51.

5. Byrd JWT. Snapping hip. Oper Tech Sports Med 2005:13:46–54.

6. Contreras ME, Dani WS, Endges WK, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of the snapping iliopsoas tendon through the central compartment of the hip. A pilot study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010;92:777–780.

7. Dobbs MB, Gordon JE, Luhmann SJ, et al. Surgical correction of the snapping iliopsoas tendon in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84A:420–424.

8. Faraj AA, Moulton A, Sirivastava VM. Snapping iliotibial band. Report of ten cases and review of the literature. Acta Orthop Belg 2001;67:19–23.

9. Fery A, Sommelet J. The snapping hip. Late results of 24 cases. Int Orthop 1988;12:277–282.

10. Flanum ME, Keene JS, Blankenbaker DG, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of the painful “internal” snapping hip: results of a new endoscopic technique and imaging protocol. Am J Sports Med 2007:35:770–779.

11. Gruen GS, Scioscia TN, Lowenstein JE. The surgical treatment of internal snapping hip. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:607–613.

12. Henry AK. Extensile Exposure, ed 2. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1973.

13. Ilizaliturri VM, Camacho-Galindo J. Endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon and iliotibial band. Oper Tech Sports Med 2011;19:114–124.

14. Ilizaliturri VM Jr, Martinez-Escalante FA, Chaidez PA, et al. Endoscopic iliotibial band release for external snapping hip syndrome. Arthroscopy 2006;22:505–510.

15. Ilizaliturri VM Jr, Villalobos FE Jr, Chaidez PA, et al. Internal snapping hip syndrome: treatment by endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon. Arthroscopy 2005;21:1375–1380.

16. Jacobson T, Allen WC. Surgical correction of the snapping iliopsoas tendon. Am J Sports Med 1990; 18:470–474.

17. Kim DH, Baechler MF, Berkowitz MJ, et al. Coxa saltans externa treated with Z-plasty of the iliotibial tract in a military population. Mil Med 2002;167:172–173.

18. Provencher MT, Hofmeister EP, Muldoon MP. The surgical treatment of external coxa saltans (the snapping hip) by Z-plasty of the iliotibial band. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:470–476.

19. Taylor GR, Clarke NMP. Surgical release of the “snapping iliopsoas tendon.” J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995;77B:881–883.

20. Velasco AD, Allan DB, Wroblewski BM. Psoas tenotomy and heterotopic ossification after Charnley low-friction arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;291:93–95.

21. Wettstein M, Jung J, Dienst M. Arthroscopic psoas tenotomy. Arthroscopy 2006;22:907.e1–e4.

22. White RA, Hughes MS, Burd T, et al. A new operative approach in the correction of external coxa saltans: the snapping hip. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1504–1508.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>