Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most successful operations performed today.3

This elective procedure provides significant pain relief and improved functional status to millions of patients globally every year.

This elective procedure provides significant pain relief and improved functional status to millions of patients globally every year.

Due to its elective nature, careful preoperative screening, evaluation, and medical workup are important to continue to reproduce or improve on the historical success of this operation.

Due to its elective nature, careful preoperative screening, evaluation, and medical workup are important to continue to reproduce or improve on the historical success of this operation.

PATHOGENESIS

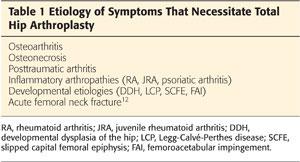

There are many varied causes of hip pain or limited function that makes a patient a good candidate for THA (Table 1).

There are many varied causes of hip pain or limited function that makes a patient a good candidate for THA (Table 1).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A detailed history and examination is necessary to delineate the etiology of the pain and functional limitations.

A detailed history and examination is necessary to delineate the etiology of the pain and functional limitations.

The history of the present illness should include, but is not limited to, the following:

The history of the present illness should include, but is not limited to, the following:

Evaluation of pain severity, quality, location, and duration

• Attention should be paid to mitigating and exacerbating factors.*

• Hip-related pain typically is felt in the groin but may present atypically as anterior thigh or knee pain.

• Functional limitations such as inability to engage in activities of daily living (ADLs), work, exercise, or have a problem with travel. Some of these patients may also be at risk of falls due to gait problems.*

Interventions attempted to date and their effectiveness

• Modification of activities

• Medications

• Injections*

• Use of assistive devices*

• Physical therapy and associated modalities*

• Weight loss*

Specific questions should be asked to differentiate true hip pain from lateral thigh pain or sciatica; for example, asking about the primary location of the pain (groin versus thigh or buttock) and associated symptoms such as radiation past the knee, distal weakness, or paresthesias.

The past medical history should include the following:

The past medical history should include the following:

Disease processes that require more extensive preoperative workup and clearance prior to surgery, such as coronary and pulmonary disorders, diabetes, and immune-related diseases, may affect surgery, anesthesia, recovery, and healing time.

Medications, especially blood thinners, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and steroids, which may need to be stopped in the perioperative period

Allergies to medication, especially antibiotics and analgesics, as well as latex allergies. For example, a patient with a documented penicillin allergy will need to have either vancomycin or clindamycin administered pre- and postoperatively for prophylaxis.4

A physical examination is important to document the preoperative status of the affected hip and ipsilateral lower extremity. It also helps identify other causes of symptoms that patients perceive as hip pain, such as back pain, where a significant number of patients have compounding pathologies.6

A physical examination is important to document the preoperative status of the affected hip and ipsilateral lower extremity. It also helps identify other causes of symptoms that patients perceive as hip pain, such as back pain, where a significant number of patients have compounding pathologies.6

A thorough neurovascular examination documents preoperative status and can indicate patients who may require more intensive preoperative testing. The examination should include the following:

A thorough neurovascular examination documents preoperative status and can indicate patients who may require more intensive preoperative testing. The examination should include the following:

Pedal pulses—if absent, ankle–brachial indices and a vascular surgery evaluation may be needed.

Distal motor strength, noting any grade of preexisting foot drop

Distal sensation

Notation of edema, skin changes, or hair loss that may indicate severe vascular dysfunction and increased risk for wound healing problems and infection

Evaluate hip range of motion in the affected leg as well as the patient’s gait.10

Evaluate hip range of motion in the affected leg as well as the patient’s gait.10

Note any preexisting limb length inequality, which will need to be addressed in the preoperative planning for correction.

Note any preexisting limb length inequality, which will need to be addressed in the preoperative planning for correction.

Evaluate the planned surgical site for preexisting scars, rashes, or plaques that may affect the approach. For example, psoriatic plaques may need to be treated and resolved prior to surgery as they present greater potential for wounds and infectious complications.1,2

Evaluate the planned surgical site for preexisting scars, rashes, or plaques that may affect the approach. For example, psoriatic plaques may need to be treated and resolved prior to surgery as they present greater potential for wounds and infectious complications.1,2

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Initial diagnostic investigation should begin with x-rays. A standard set that includes an anteroposterior (AP) pelvis, AP hip, and frog-leg lateral versus cross-table lateral should be obtained.

Initial diagnostic investigation should begin with x-rays. A standard set that includes an anteroposterior (AP) pelvis, AP hip, and frog-leg lateral versus cross-table lateral should be obtained.

In addition to evaluating the extent of arthritis, imaging studies are used for preoperative planning via digital or acetate templating. A standardized marker should be placed at the level of the joint to allow for correction of magnification. In the case of dysplasia, x-rays of the contralateral hip can be helpful in templating for the size of components.13 If initial x-rays appear inconsistent with the extent of the patient’s complaints, further investigation may be undertaken.5

In addition to evaluating the extent of arthritis, imaging studies are used for preoperative planning via digital or acetate templating. A standardized marker should be placed at the level of the joint to allow for correction of magnification. In the case of dysplasia, x-rays of the contralateral hip can be helpful in templating for the size of components.13 If initial x-rays appear inconsistent with the extent of the patient’s complaints, further investigation may be undertaken.5

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can demonstrate preradiographic avascular necrosis, transient osteoporosis, labral pathology, and occult hip fractures.

Bone scan can be used when a patient is not able to undergo MRI.

Computed tomography scan can be used to evaluate bony morphology in cases of congenital or posttraumatic deformity.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Healthy patients with functional limitations related to their pathology who have failed conservative management are good candidates for THA.

Healthy patients with functional limitations related to their pathology who have failed conservative management are good candidates for THA.

Young, healthy patients with bilateral disease in which both hips are indicated for surgery may undergo a one-stage bilateral THA, a procedure that has been proven to have lower complication rates and significant cost savings compared to two-stage procedures.7

Young, healthy patients with bilateral disease in which both hips are indicated for surgery may undergo a one-stage bilateral THA, a procedure that has been proven to have lower complication rates and significant cost savings compared to two-stage procedures.7

Absolute contraindications for surgery

Absolute contraindications for surgery

Patients with active infections

Patients not medically cleared should be managed with nonoperative measures until the underlying disease preventing operative candidacy is treated.

Relative contraindications for surgery

Relative contraindications for surgery

Morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI] >40 kg/m2)9

Uncontrolled diabetes8

Narcotic dependence

Active smokers11

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Various approaches and techniques for fixation will be discussed in the following chapters.

Various approaches and techniques for fixation will be discussed in the following chapters.

Preoperative Planning

Consent: After determining a patient is a satisfactory candidate for THA, a detailed discussion must be had that details the diagnosis and prognosis for the patient’s condition. Risks, benefits, and alternatives to surgery (including their inherent risks and benefits) should be discussed with the patient at this time.

Consent: After determining a patient is a satisfactory candidate for THA, a detailed discussion must be had that details the diagnosis and prognosis for the patient’s condition. Risks, benefits, and alternatives to surgery (including their inherent risks and benefits) should be discussed with the patient at this time.

The surgeon and patient should approach informed consent from a shared decision-making perspective. This leads to greater patient investment in and cooperation with the plan of care, improved outcomes, and decreased risk of medical malpractice claims.14

The surgeon and patient should approach informed consent from a shared decision-making perspective. This leads to greater patient investment in and cooperation with the plan of care, improved outcomes, and decreased risk of medical malpractice claims.14

Once a patient has elected to undergo surgery, there are several steps that must be completed prior to conducting the procedure. The protocol committee at our institution recommends the following as part of the preoperative assessment for primary joint replacement candidates:

Once a patient has elected to undergo surgery, there are several steps that must be completed prior to conducting the procedure. The protocol committee at our institution recommends the following as part of the preoperative assessment for primary joint replacement candidates:

Routine preoperative testing consists of a complete blood count (CBC) and chem-7 panel. In diabetic patients, hemoglobin A1c may be evaluated at the discretion of the surgeon.

Urinalysis should be considered for symptoms consistent with a urinary tract infection (UTI), a UTI in the past 6 months, a history of diabetes mellitus, a history of prostate disease, or a history of urologic surgery requiring instrumentation.

Preoperative clearance must be obtained from appropriate medical doctors as the patient’s past medical history dictates.

Dental evaluation should be undertaken to ensure there are no active infections prior to surgery.

For patients with a BMI greater than 40, weight reduction should be attempted prior to surgery. For those who are unable to meet this goal, a discussion regarding the increased risk for perioperative complications should be conducted.

Patients on aspirin should not stop taking it prior to surgery due to increased cardiac risk.

Patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should not stop these medications prior to surgery as the increase in preoperative pain can make postoperative pain control more difficult. However, the surgeon must accept the potential for increased perioperative bleeding.

Plavix, Aggrenox, and Coumadin should all be stopped 1 week prior to the planned surgery and Pradaxa and Xarelto stopped at least 3 days before. If the patient is not an appropriate candidate for neuraxial anesthesia and general anesthesia is planned, the patient may continue these medications as indicated by his or her medical consultants.

Patient education programs are a valuable resource to help a patient prepare his or her expectations related to the surgery, hospitalization, and subsequent recovery.

Preoperative skin cleansing should begin at home prior to the day of surgery. The International Consensus on Periprosthetic Joint Infection (http://www.msis_na/internationalconsensus) recommends the use of over-the-counter Hibiclens for 2 days preoperatively.

* = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service requirements

REFERENCES

1. Day MS, Nam D, Goodman S, et al. Psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012;20:28–37.

2. Della Valle C, Parvizi J, Bauer T, et al. The diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infections of the hip and knee. Guideline and evidence report. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Web site. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/PJIguideline.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2014.

3. Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. Lancet 2007;370:1508–1519.

4. Matar WY, Jafari SM, Restrepo C, et al. Preventing infection in total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:36–46.

5. Newberg AH, Newman JS. Imaging of painful hip. In: McCarthy JC, ed. Early Hip Disorders: Advances in Detection and Minimally Invasive Treatment. New York: Springer, 2003:17–43.

6. Parvizi J, Pour A, Hillibrand A, et al. Back pain and total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:1325–1330.

7. Parvizi J, Tarity TD, Sheikh E, et al. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty: one-stage versus two-stage procedures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 453:137–141.

8. Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Johnsen SP, et al. Risk of revision of a total hip replacement in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010;92-B:929–934.

9. Rajopal R, Martin R, Howard JL, et al. Outcomes and complications of total hip replacement in super-obese patients. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B:576–763

10. Roder C, Staub L, Eggli S, et al. Influence of preoperative functional status on outcome after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:11–17.

11. Singh J. Smoking and outcomes after knee and hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1824–1834.

12. Tidermark J, Ponzer S, Svensson O, et al. Internal fixation compared with total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003;85-B:380–388.

13. Unnanuntana A, Wagner D, Goodman S. The accuracy of preoperative templating in cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2009;24:180–186.

14. Youm J, Chenok KE, Belkora J, et al. The emerging case for shared decision making in orthopaedics. Instr Course Lect 2013;62: 587–594.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>