Facial Bipartition

Jessica A. Ching

Christopher R. Forrest

DEFINITION

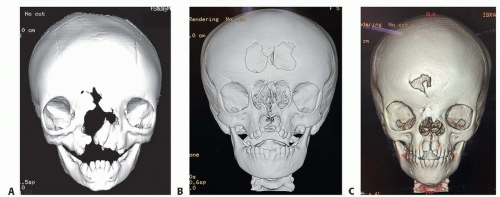

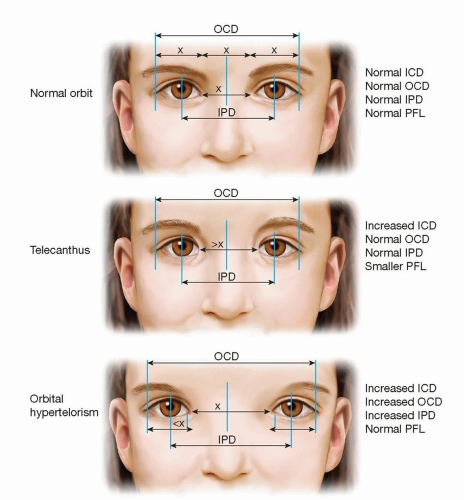

Orbital hypertelorism, or hypertelorbitism, is increased distance between the bony orbits and represents true lateralization of the orbits (FIG 1).

Interorbital hypertelorism is defined as increased distance between the medial orbital walls.

Telecanthus is an increased distance between the medial canthi with a normal interorbital distance and associated with a normal interpupillary distance.

The severity of hypertelorism may be interpreted according to patient age.

The presence of an epicanthal fold can give the illusion of hypertelorism and may be termed pseudohypertelorism.

Hypertelorism is a clinical finding, not a diagnosis, and is etiologically heterogeneous.

It may be surgically corrected through facial bipartition, 360-degree box orbital osteotomy, segmental orbital osteotomy, or a camouflage rhinoplasty.

Facial bipartition is a complex craniofacial osteotomy developed by Paul Tessier after first being described by van der Meulen.1,2 This technique separates the frontal-orbital-zygomatic-maxillary complex from the skull base and removes a segment of bone between the medial nasal-orbital region and splits the palate down the middle—mobilization allows for a medialization and rotation of the orbits with lateralization and expansion of the maxillary arch and lengthening of the midface.

It is traditionally performed for less severe cases of hypertelorism.

Facial bipartition may be performed in conjunction with a frontofacial monobloc advancement procedure.

Facial bipartition can be performed in the young patient, whereas 360-degree box orbital osteotomies are usually performed in older children when the maxillary sinuses have developed, tooth buds descended and orbits have near-completed growth around age 7 years.

ANATOMY

The degrees of hypertelorism may be measured using soft tissue and bony landmarks.

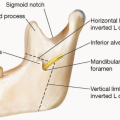

The dacryon is the most medial portion of the bony orbit, lying at the intersection of the frontal, lacrimal, and maxillary bones. This is the most common landmark for measuring interorbital distance (IOD).

Important bony landmarks are used to measure the inner canthal distance (ICD) between the two medial canthi measured at the level of the posterior lacrimal crest and the outer canthal distance (OCD) measured between the two lateral canthi.

The interpupillary distance (IPD) between the two midpupillary regions in front gaze is a useful measure, but taken by itself, increased IPD may not be indicative of hypertelorism. It may be seen in post-traumatic cases or in cases of exophoria due to extraocular muscle imbalance.

ICD, OCD, and IPD are always increased in cases of true hypertelorism (FIG 2).

Hypertelorism exhibits an increased IOD due to intervening excess bone and soft tissue.

IPD will be increased, and orbital aperture dimensions (height and width) are usually normal.

For children, the average interorbital distance increases with age3:

1 year old: 18.5 mm

2 years old: 20.5 mm

3 years old: 21 mm

5 years old: 22 mm

7 years old: 23 ± 4 mm

10 years old: 25 ± 2 mm

12 years old: 26 ± 1 mm

For adults, average interorbital distance is 25 mm in women and 28 mm in men.3

Degree or severity of hypertelorism is graded in children and adults by the amount of deviation from the average interorbital distance (Table 1).

PATHOGENESIS

During embryologic development, lateral optic placodes move medially during weeks 5 to 9 and become the orbits and associated ocular structures.

A persistent divergence of the orbital axes reflects early developmental arrest.

Mechanisms of arrest include the following:

Deficient growth affecting the brain and eyes

Deficient closure of the rostral neuropore with the development of sincipital encephaloceles

Deficient differentiation of the nasal capsule

Compensatory accommodation of the cranial base to the growing brain

Hypertelorism may result from syndromic and nonsyndromic etiologies, such as

Encephalocele (nasofrontal, nasoethmoidal, naso-orbital, and combined)

Craniofrontonasal dysplasia

Median facial clefting or frontonasal dysplasia

Syndromic craniofacial dysostoses (ie, Apert, Crouzon, Pfeiffer)

Tumors

Vascular malformations

NATURAL HISTORY

Hypertelorism may remain stable or worsen with growth, depending on the etiology, but it does not improve over time.

Relapse is common when surgery is performed in young children (under 8 years of age).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The preoperative evaluation includes assessment of prenatal and birth history, general development, medical diagnoses, genetic findings, family history of similar conditions, the level of patient’s and parents’ concern regarding the hypertelorism, psychosocial issues, and eagerness to undergo surgical correction for hypertelorism.

A history of sleep disordered breathing may suggest the need for a frontofacial advancement to increase the size of the airway.

Previous intracranial surgical history is important to document including cranio-orbital reshaping and insertion of a VP shunt.

Physical examination: a basic examination of the head and neck is mandated with specific attention paid toward the cranio-orbital and midface region.

Soft tissue measurements including ICD, OCD, and IPD are documented recognizing that soft tissue intercanthal measurements can be increased greater than 10 mm over underlying bone measurements.5

Presence or absence of midface and zygomatic hypoplasia

Nasal appearance recognizing that hypertelorism may be masked by surgical augmentation of a depressed nasal dorsum

Other contributors to the appearance of hypertelorism should also be assessed, such as exotropia, dystopia canthorum, epicanthal folds, narrow palpebral fissures, and widely spaced eyebrows.

Extraocular muscle function, gross vision, presence of exorbitism, and degree of corneal protection should be noted.

Evaluate for soft tissue excess that may be present or be created by medialization of the orbits.

In assessing the need to correct hypertelorism, a technique to obscure the naso-orbital region can help determine whether the lateral orbital wall distances are abnormal and if so, would necessitate either facial bipartition or box osteotomies. If not, then medial wall osteotomies or camouflage rhinoplasty procedures would be effective (FIG 3).

The cranial shape and fontanelle patency should be assessed for associated craniosynostosis in cases of craniofrontonasal dysplasia and craniofacial dysostoses, which may alter surgical planning.

Further examination should identify other findings suggestive of an underlying syndromic diagnosis, which may influence treatment planning and timing such as midface retrusion, severe exorbitism, and indications of elevated intracranial pressure.

Preoperative consultations are routinely obtained from ophthalmology, neurosurgery, and anesthesia.

IMAGING

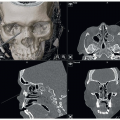

Preoperative imaging with computed tomography (CT) scans (axial, sagittal, and coronal) of the craniofacial skeleton should be obtained, preferably with a low-dose, bone-only window radiation protocol to obtain a 3D reconstruction for full visualization of the craniofacial region.

MRI is indicated for assessment of midline tumors and encephaloceles and to assess the hypothalamic-pituitary system in specific cases.

Vascular studies (CT angiogram/venogram, MR angiogram). A CT arteriogram and venogram of the head and neck, or comparable vascular study, may be indicated in select cases for the purpose of identifying cerebral venous drainage anomalies commonly found in these patients as well as the vascular pathways in cases of encephaloceles.

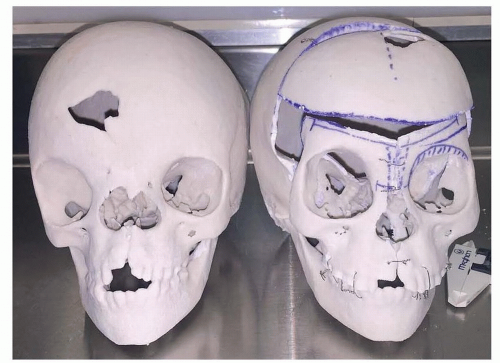

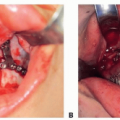

Printing of 3D surgical models from CT scans is of great benefit in surgical planning and mock surgery (FIG 4).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The following conditions should be considered when assessing a patient with hypertelorism for a facial bipartition procedure.

Sincipital encephaloceles (nasofrontal, nasoethmoidal, naso-orbital, and combined)

Craniofrontonasal dysplasia

Facial clefting and frontonasal dysplasia

Craniofacial dysostoses (eg, Apert, Crouzon, Pfeiffer)

Tumors

Vascular malformations

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Hypertelorism does not always necessitate operative intervention.

A mild degree of hypertelorism is considered attractive and may not warrant extensive surgical procedures for correction.

Surgical management of hypertelorism may be directed toward the nose as a camouflage procedure such as nasal dorsal augmentation and correction of epicanthal folds.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications

Facial bipartition is indicated to simultaneously correct mild to moderate hypertelorism and maxillary arch constriction with anterior open bite deformity.

Hypertelorism with concomitant intracranial hypertension and/or airway compromise due to midface retrusion are indications to combine the facial bipartion with a frontofacial monobloc advancement procedure.

Facial bipartition when performed as a distraction advancement is effective in “unbending” the facial concavity associated with Crouzon, Pfeiffer, and Apert syndromes.

Facial bipartition works best with symmetric conditions.

Facial bipartition may be performed safely in young (less than 5 years) children but can be associated with high rates of relapse when performed at this age.

Surgical timing of facial bipartition requires consideration of several factors.

The older the patient, the less likely there will be postoperative relapse of hypertelorism.

Some studies indicate performing facial bipartition in children less than 6 to 8 years old has a high degree of relapse on long-term follow-up.6,7

Timing of surgery must account for the child’s psychosocial development and interaction with peers.

A midline cleft or encephalocele may leave the brain vulnerable to injury.

Surgical management of sincipital encephaloceles is out of the scope of this chapter but is best performed in infancy.

Severe hypertelorism may affect development of stereotactic vision if treatment is delayed; however, this is not well substantiated.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree