Fig. 17.1

(a) Thirty-nine-year-old female with right breast invasive ductal carcinoma , following right nipple-sparing mastectomy, tissue expander placement, and postmastectomy radiation therapy. The right breast has healed and the nipple has tolerated postmastectomy radiation therapy. (b) The patient 2.5 years after exchange of her right breast tissue expander for permanent silicone implant, and small left breast augmentation

These findings clearly illustrate the higher complication rates of prosthetic breast reconstruction following NSM, in the setting of postmastectomy radiation therapy. However, the 17.7 % explantation rate in this population is a reduction from the 40 % explantation rate reported previously by other groups radiating tissue expanders prior to implant exchange [18]. The improvement in the author’s outcomes over time, is largely attributed to the increased experience of surgical oncologists performing NSM. With this increased experience, the ability to adequately remove the nipple parenchyma while preserving vascularity of the NAC skin has improved, thus offering enhanced resistance to complications in the setting of radiation.

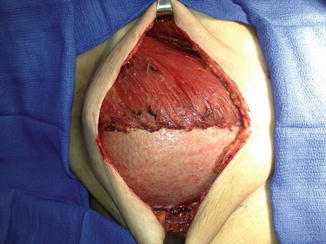

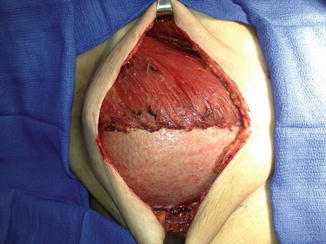

Use of ADM in the Setting of NSM and PMRT

An additional protective effect in reduction of complications in the setting of XRT, even with the addition of NSM, is seen with the addition of acellular dermal matrix (ADM) to assist in coverage of the tissue expander at time of placement [23]. These matrices are aseptically processed sheets of human cadaveric dermis that retains its collagen matrix and allows for host cell repopulation and revascularization [24]. The use of ADM to fully or partially cover the tissue expander at time of placement following mastectomy, particularly along the lower pole of the device for support and stability, has become a common technique among reconstructive surgeons (Fig. 17.2). Numerous studies have now illustrated that the use of these devices carries a safety profile similar to those achieved with traditional full submuscular coverage of the prosthetic device s [25, 26].

Fig. 17.2

Acellular dermal matrix placed at time of mastectomy over tissue expander , for lower pole coverage and support of the tissue expander

It has previously been established that ADM maintains integrity and functions well in the setting of radiation therapy [24]. Additional data has now shown that the use of ADM for assistance in tissue expander coverage following NSM, offers a reduced complication rate in the setting of postmastectomy radiation [22]. When compared to the population of NSM patients undergoing tissue expander placement and radiation without ADM coverage of the device, those with ADM assisted device coverage exhibited lower rates of infections requiring operative intervention (RR 4.30 vs. .48, p = 0.041) and lower rates of expander/implant loss (RR 4.46 vs. 2.41, p = 0.262).

This clinically protective effect of ADM in the setting of XRT is likely multifactorial, and related in part to the improved physical support of the expander along the lower pole, in the area where it places the most weight and tension on the skin flaps during radiation, once it has been filled. This hammock of ADM likely offloads some of the weight of the expander, thus resulting in less pressure on the lower pole skin flaps, and thus less risk of breakdown or wound dehiscence, and resulting prosthetic device exposure.

This reduction in complication and explantation rates of prosthetic devices conferred by ADM in the setting of NSM and XRT has also been illustrated by other high volume centers performing these procedures [27, 28]. When comparing immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction with the use of ADM assisted tissue expander coverage vs. no ADM use, Seth et al. reported a statistically significant reduction in total complications and infection with the use of ADM [27]. When performing immediate tissue expander coverage with ADM in breasts undergoing postmastectomy radiation therapy, Spear et al. reported a 21.4 % explantation rate [28]. Again, this is lower than the findings reported by Nava et al. (40 % explantation rate) when using full submuscular coverage without ADM assistance, prior to radiation delivery [18].

In all cases, consistent and reproducible results have been achieved in this setting. These findings have led the author’s group to consistently utilize ADM for tissue expander coverage at the time of mastectomy in all cases in which postmastectomy radiation is known or anticipated.

Effect of Mastectomy Incision Location on Outcomes

Another technical aspect of surgery, in the setting of postmastectomy radiation, that has been found to significantly affect outcomes, is the mastectomy incision location. Clinical evidence has shown that the inframammary incisions used for NSM and reconstruction result in a higher wound dehiscence and complication rate when subjected to radiation therapy, relative to all incisions on nondependent locations of the breast [29]. These include periareolar and lateral/radial incisions.

The increased rate of complications seen with the inframammary (IMF) approach, in the setting of radiation, is likely due to the weight of the full tissue expander or implant sitting directly on the incision. This increased weight places additional stress directly on the IMF incision. Furthermore, with the IMF incision, the mastectomy skin just above the incision, on the lower pole of the breast, is relatively poorly perfused, given its distance from branches of the internal mammary artery perforators. Furthermore, the skin in this location receives minimal perfusion from the abdominal perforators, given the interruption of this blood supply by the incision location.

These factors account for the reduced ability of the inframammary incision to withstand complications relative to other incision locations, in the setting of radiation. For this reason, the author’s preference is a periareolar or lateral radial incision for mastectomy and reconstruction, when postmastectomy radiation is anticipated.

Timing of Expander Exchange for Permanent Implant

The timing of tissue expander exchange for permanent breast implant, following completion of radiation therapy, must also be carefully considered. There are proponents of performing this exchange operation early after completion of radiation therapy, before radiation fibrosis fully occurs. Surgeons in favor of this timing maintain that the skin and capsule are still soft and malleable at this point, allowing for improved tissue handling and healing.

However, the skin in this acute period following completion of radiation therapy is in an acute inflammatory state [30]. This state is not conducive to healing following surgery. Published evidence has supported this finding. It has been shown in clinical series, that waiting at least 6 months following completion of radiation, prior to performing the expander exchange for implant, reduces complication rates from 22.4 to 7.7 % in this population [31]. The most common complications encountered are wound dehiscence and cellulitis.

These reduced complications with prolonged waiting periods greater than 6 months following radiation completion, are likely explained by two major factors. First, in vivo studies have shown that endothelial damage from radiation, causing reduced dermal blood flow, occurs between 2 and 6 months after radiation, and levels off after this [32]. Second, imaging studies have shown that the breast edema and skin thickening induced by radiation therapy, peak at 6 months after treatment initiation, then reduce from this point forward [33].

As a result, it is advisable to wait 6 months or longer, following completion of radiation therapy, before performing the implant exchange operation. At that time, a second consideration in operative planning is incision placement. The original mastectomy incision will consist primarily of radiated scar tissue, which will offer reduced healing potential over the prosthetic device. It is advisable at this operation to consider a new counter incision in a separate location of the breast.

The optimal incision location following radiation is the lateral breast, approximately 5 mm below the inframammary fold. In this area, the tissue is of abdominal origin. Thus, there is a thicker area of fascia, subcutaneous tissue, and skin, that may be used in closure. Although this area is usually in the radiation field, it has not been previously incised, so is devoid of scar tissue. Furthermore, the multilayer closure is more durable to withstand full thickness dehiscence. Reusing the original mastectomy incision, at any location on the breast, results in closure o f a very thin, often 1- or 2-layer closure of radiated scar tissue under tension.

Given this, it is encouraged to plan the original mastectomy incision with the exchange incision in mind. The preferred location, when PMRT is anticipated, is a periareolar incision for the mastectomy and tissue expander placement, and a lateral incision just below the IMF for the exchange operation. The author’s experience has shown that this offers the lowest morbidity rate.

Aesthetic Outcomes with NSM and XRT

Aesthetic outcomes with NSM and prosthetic reconstruction have been mixed. In general, patients report a loss of nipple projection and pigmentation on long term follow up, without radiation [8]. Satisfaction regarding nipple/areola aesthetics remains mixed among these patients. The addition of radiation therapy increases loss of projection and hypopigmentation of the NAC. Furthermore, reduction of areola diameter is routinely experienced, making NAC asymmetry common in unilateral reconstruction cases [11].

Following radiation, positional asymmetries in the NAC are exceedingly difficult to correct, given the radiation fibrosis of the breast skin [34]. This is primarily due to the inability of transposition flaps, used for NAC positional changes, to heal properly. Additionally, the skin fibrosis results in reduced ability to transpose and rotate skin significant distances.

Thus, great care must be taken to fix the nipple at the time of mastectomy in the correct location and allow it to heal to the underlying tissue, in the first few postoperative weeks. Thus, it is routine practice now to suture the NAC to underlying pectoralis muscle or acellular dermal matrix at the time of mastectomy, with a dissolvable suture. Once the NAC heals in the correct position, it is unlikely to be displaced during radiation therapy, or require significant repositioning after completion of radiation.

Operative Algorithm for Prosthetic Reconstruction with NSM and PMRT

Given all these factors, the author has developed an operative algorithm for patients undergoing NSM and prosthetic reconstruction in the setting of PMRT. All patients undergo immediate tissue expander placement with the addition of acellular dermal matrix to assist in expander coverage. For the mastectomy, the periareolar incision is used preferentially, given previous data findings that this offers a lower dehiscence rate in the setting of PMRT. If the patient has mild breast ptosis preoperatively, then this periareolar incision can be planned as a small crescent mastopexy with modest skin removal, allowing for NAC elevation.

A tissue expander with suture tabs is used in these patients, to prevent migration of the expander induced by tissue contraction during radiation. These patients are fully expanded prior to radiation therapy, and usually over expanded, to allow for additional tissue laxity during the exchange operation. It is important to avoid expander deflation of the radiated side during PMRT. Keeping the expander inflated does not interfere with radiation delivery, and also avoids reexpansion of the radiated breast following completion of PMRT [35]. It is the expansion and reexpansion of a radiated soft tissue envelope that causes much of the wound breakdown and keeping the expander inflated allows for avoidance of reexpansion.

Finally, following completion of PMRT, the author waits a minimum of 6 months prior to the exchange operation. The author’s institution has shown this to offer a reduced wound dehiscence risk, relative to proceeding sooner [31]. At this exchange operation, a new incision, just below the lateral inframammary fold is used preferentially. This allows for multilayer operative closure in an area of thick, abdominal subcutaneous tissue and skin, which has not been previously incised, and thus does not contain scar tissue. Using this algorithm, consistent outcomes have been achieved in this challenging patient population [22].

Effects of Axillary Node Dissection on Outcomes

Another consideration that must be made when considering prosthetic reconstruction following NSM is the axillary lymph node status. There is clear data showing that the combination of radiation therapy, and primary axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), significantly accelerates complication rates in this patient population. Specifically, risk of implant loss in this population stands at 13 % following second-stage expander/implant exchange in NSM patients [36].

When compared with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), full primary axillary lymph node dissection carries a significantly increased risk of implant loss (RR 3.8), independent of all other risk factors [36]. With the addition of radiation, these patients need to be counseled strongly on their risk, and encouraged to consider either breast conservation with oncoplastic reconstruction, or autologous reconstruction following NSM [37, 38].

Unlike ALND, similar data has shown that hormonal therapy does not carry a significant effect on implant failure rates [36]. Thus, patients on these adjuvant treatments can safely undergo prosthetic reconstruction following NSM.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree