Abstract

The term eczema is derived from the Greek word that means “to boil out or over.” It is a convenient “wastebasket” for many undiagnosed rashes but is best applied to epidermal eruptions that are characterized histologically by intercellular edema, called spongiosis ( Table 8.1 ). Eczema and dermatitis are synonyms. Acute dermatitis has a marked amount of spongiosis causing vesiculation. Subacute dermatitis has less spongiosis, resulting in “juicy papules.” Chronic dermatitis involves a markedly thickened epidermis ( lichenification ) with only slight spongiosis.

Chapter Contents

Uncommon Eczematous Appearing Diseases

- 1.

Appearance varies from blisters to scaling, lichenified plaques

- 2.

Itching is prominent

- 3.

Distribution can be localized or generalized

Types of dermatitis:

- 1.

Acute – vesicles

- 2.

Subacute – juicy papules

- 3.

Chronic – lichenification

The hallmarks of dermatitis are marked pruritus, indistinct borders (except for contact dermatitis), and epidermal changes characterized by vesicles, juicy papules, or lichenification. Dermatitis may be localized or diffuse; it may be idiopathic or may have a specific cause. Contact allergy is the best understood cause of an eczematous reaction, and potentially the most correctable. For any eczematous rash, the first question to be asked is: “Could it be contact dermatitis?”

If it does not itch, reconsider the diagnosis of dermatitis.

Atopic Dermatitis

- 1.

Itching is prominent

- 2.

The antecubital and popliteal fossae are typically affected

- 3.

Chronic waxing and waning course

| Frequency a | History | Physical Examination | Differential Diagnosis | Laboratory Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atopic dermatitis | 2.6 | Allergic rhinitis Asthma | Vesicles, juicy papules – infants Lichenified plaques – adults and older children Head, neck, antecubital and popliteal fossa | Contact dermatitis Scabies Immunodeficiency syndromes Langerhans cell histiocytosis | IgE |

| Contact dermatitis | 2.8 | Irritant: contact precedes rash by hours to days Allergic: contact precedes rash by 1–4 days | Vesicles, juicy papules, lichenified plaques Sharp margins Geometric or linear configuration Conforms to area of contact | Eczematous dermatitis Fungal infection Cellulitis | Patch test |

| Essential dermatitis | 11.4 | Pruritus | Acute: vesicles, weeping, crusted patches Subacute: juicy papules Chronic: lichenified, scaling plaques | Contact dermatitis Atopic dermatitis Seborrheic dermatitis Fungal, viral, or bacterial infection Psoriasis Drug rash Dermatitis herpetiformis | – |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | 0.8 | Rash subsequent to pruritus | Lichenified plaque within reach of fingers | Contact dermatitis | – |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 3.7 | Dandruff | Scaling papules and patches Scalp, eyebrows, nose, sternum | Atopic dermatitis Psoriasis Fungal infection Langerhans cell histiocytosis Lupus erythematosus Rosacea Perioral dermatitis | – |

| Stasis dermatitis | 0.4 | Varicose veins Leg swelling Thrombophlebitis | Juicy papules Lichenified plaques Brown pigmentation Lower legs | Cellulitis Contact dermatitis Fungal or bacterial infection | – |

a Percentage of new dermatology patients with this diagnosis seen in the Hershey Medical Center Dermatology Clinic, Hershey, PA.

Definition

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, relapsing, intensely pruritic, inflammatory condition of the skin that is associated with a personal or family history of atopic disease (e.g., asthma, allergic rhinitis, or atopic dermatitis). The cause of atopic dermatitis is thought to be altered skin barrier and immune function. Patients appear to have a genetic predisposition that can be exacerbated by numerous factors, including food allergy, skin infections, irritating clothes or chemicals, change in climate, and emotions. Lichenification is the clinical hallmark of chronic atopic dermatitis ( Fig. 8.1 ).

Incidence

Atopic dermatitis is predominantly a disease of childhood, with 17% of children and 6% of adults affected. It usually starts after 2 months of age, and by 5 years of age, 90% of the patients who will develop atopic dermatitis have manifested the disease. It is uncommon for adults to develop atopic dermatitis without a history of childhood eczema.

History

A history of allergic respiratory disease is found in one-third of patients with atopic dermatitis and in two-thirds of their family members. Pruritus ( Fig. 8.1D ) is the most distressing and prominent symptom.

- ●

Pruritus

- ●

Typical morphology and distribution

- ●

Flexural lichenification in adults and older children

- ●

Facial and extensor papulovesicles in infancy

- ●

Chronic – relapsing course

- ●

Personal or family history of atopic disease

- ●

Lichenification is the clinical hallmark of chronic atopic dermatitis

Physical Examination

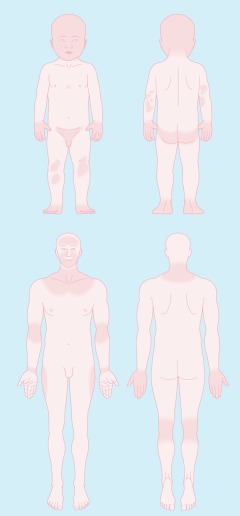

The morphology and distribution of atopic dermatitis are age-dependent ( Fig. 8.2 ). Infantile atopic dermatitis is characterized by acute-to-subacute eczema with papules, vesicles, oozing, and crusting. It is distributed over the head, diaper area, and extensor surfaces of the extremities. In children and adults, the eruption is a chronic dermatitis with lichenification and scaling. The distribution includes the neck, face, upper chest, and, characteristically, antecubital and popliteal fossae ( Fig. 8.1 ).

Atopic dermatitis in infants is papular or vesicular; in children and adults, it is lichenified, especially affecting the antecubital and popliteal fossae.

Individuals with atopic dermatitis have a characteristic expression. The face has mild to moderate erythema, perioral pallor, and infraorbital folds (Dennie–Morgan lines) associated with dermatitis and hyperpigmentation. The skin generally is dry and may have generalized fine, whitish scaling. The palms often have increased linear markings.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of atopic dermatitis includes other eczematous eruptions and scabies . The history of other family members with pruritus and a thorough skin examination that reveals burrows, particularly on the hands, are diagnostic of scabies. Infants with Langerhans cell histiocytosis and immunodeficiency syndromes such as Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia , and Swiss-type agammaglobulinemia have dermatitis that resembles atopic dermatitis, but these conditions are rare, and the infants have systemic symptoms that distinguish their conditions from atopic dermatitis.

- ●

Contact dermatits

- ●

Scabies

- ●

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- ●

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

- ●

Ataxia–telangiectasia

- ●

Swiss-type agammaglobulinemia

Laboratory and Biopsy

The diagnosis of atopic dermatitis is made clinically. The skin biopsy (rarely required) reveals an eczematous change that is not specific for atopic dermatitis ( Fig. 8.1B ). Serum immunoglobulin (Ig)E concentration is frequently raised, but usually is not necessary to make the diagnosis.

Therapy

The treatment of atopic dermatitis is the same as for other eczematous eruptions and includes topical steroids, topical macrolide immunosuppressants, and systemic antihistamines. However, the use of antihistamines to reduce pruritus is largely unproven. Only sedating antihistamines may be effective for itching that interferes with sleep. Treatment should be given in appropriate strength and frequency to reduce inflammation and itching significantly. A common error is under treatment. Occasionally, a short course of systemic steroids (prednisone) is necessary to bring the disease under control. Wet dressings (plain water) and bleach baths are helpful in treating acute atopic dermatitis. Avoidance of environmental factors that enhance itching, such as woolen clothes, emotional stress, and uncomfortable climatic conditions, is important. Moisturizers reduce dry skin and itching. Ultraviolet radiation B (UVB), psoralen plus ultraviolet radiation A (PUVA), or other systemic immunosuppressants – cyclosporine (Neoral), azathioprine (Imuran), mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept), and dupilumab (Dupixent) – may be considered if satisfactory control is not achieved with initial treatment.

To be successful, treatment must eliminate pruritus.

In some children, food allergy can cause atopic dermatitis. Skin testing or radioallergosorbent tests may help to identify foods that are responsible. Positive tests must be confirmed with controlled food challenges and elimination diets. Eggs, peanuts, milk, and wheat appear to be the most frequently offending foods. Investigators have suggested that atopic dermatitis can be prevented by avoiding cow’s milk, wheat, and eggs for the first 6 months of life. However, this approach is controversial and not generally recommended. Patients with atopic dermatitis have a higher frequency of immediate skin test reactivity in general, but hyposensitization is rarely of value in atopic dermatitis. As a last resort, severe atopic dermatitis is treated with systemic immunomodulants.

Initial

- ●

Moisturizers

- ●

Avoidance of irritants – woolen clothes, harsh soaps, uncomfortable climate

- ●

Steroids, topical macrolide immunosuppressants, crisaborole ointment, antihistamines, baths, compresses, and antibiotics (see Therapy for Essential Dermatitis, below)

- ●

Avoidance of food allergens (eggs, peanuts, milk, wheat) in selected patients

Alternative

- ●

Ultraviolet light – UVB, PUVA

- ●

Immunomodulants – azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, dupilumab

- ●

Support group – National Eczema Association for Science and Education, www.nationaleczema.org

Course and Complications

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic disease punctuated by repeated acute flare-ups followed by longer periods of slow resolution. The cause of these flare-ups is frequently unknown – a feature that adds to the frustration of this disease. Most children (90%) outgrow their disease by adolescence, although as adults, some continue to have localized forms of atopic dermatitis such as chronic hand or foot dermatitis, patches of lichen simplex chronicus, or eyelid dermatitis. Longitudinal studies suggest an “atopic march” in which over half of infants and children with atopic dermatitis will progress to develop allergic rhinitis and asthma.

Atopic dermatitis is frequently complicated by skin infections. Atopic skin has a higher rate of colonization with Staphylococcus aureus . The most serious cutaneous infection is Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption . This widespread vesiculopustular eruption is caused by herpes simplex (eczema herpeticum), variola, or vaccinia virus. Patients with this infection are acutely ill and may die; for this reason, smallpox immunization was contraindicated in these patients. The hyper-IgE syndrome refers to a syndrome of atopic dermatitis characterized by recurrent pyoderma (skin infections), raised serum IgE levels, and decreased chemotaxis of mononuclear cells.

Bacterial and viral skin infections are common in atopic dermatitis.

Pathogenesis

Atopic dermatitis is a multifactorial cutaneous inflammatory disease caused, in part, by gene polymorphismisms affecting the innate and adaptive immune response and the epidermal barrier function. A disrupted skin barrier (filaggrin gene mutation) and disturbed immunologic response (Th2 + Th1 cytokines, and IgE) have been implicated in the etiology of atopic dermatitis. The epidermal barrier defect results in dry skin and penetration of irritants, microbes, and antigens. The immunologic changes are most notable and frequent in patients with severe atopic dermatitis. These changes include raised serum IgE levels, defective cell-mediated immunity, decreased chemotaxis of mononuclear cells, increased T-lymphocyte activation with production of T helper Th1 and Th2 cytokines, and hyper stimulatory Langerhans cells. The increased IgE concentration is thought to reflect decreased numbers of T-suppressor cells and uninhibited production of IgE. Depressed cell-mediated immunity is manifested by an increased susceptibility to cutaneous viral and bacterial infections. In addition, responses to in vitro tests of cell-mediated immunity such as lymphocyte blastogenesis to mitogens and antigens are blunted. There are also low levels of antimicrobial peptides in lesional skin resulting in increased susceptibility to pathogens such as S. aureus , herpes simplex virus, and vaccinia virus.

Disruption of the skin barrier and immune dysfunction contribute to the development of atopic dermatitis.

Contact Dermatitis

- 1.

Irritant or allergic etiology

- 2.

Distribution conforms to areas of contact

- 3.

Avoidance of the contactant results in cure

Definition

Contact dermatitis ( Fig. 8.3 ) is an inflammatory reaction of the skin precipitated by an exogenous chemical. The two types of contact dermatitis are irritant and allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis is produced by a substance that has a direct toxic effect on the skin. Allergic contact dermatitis triggers an immunologic reaction that causes tissue inflammation. Examples of irritants include acids, alkalis, solvents, and detergents. Innumerable chemicals cause allergic contact dermatitis, including metals, plants, medicines, cosmetics, and rubber compounds. Clinical appearance can range from acute (vesicles) to chronic (lichenification) eczematous reactions.

Types of contact dermatitis:

- 1.

Irritant

- 2.

Allergic

Incidence

Contact dermatitis is a frequent problem that most people experience during their lifetime, whether it is irritant diaper dermatitis or allergic poison ivy or oak dermatitis. A significant cause of occupational illness (excluding injury) is caused by contact dermatitis, resulting in impairment and time lost from work. In occupational contact dermatitis, irritant is usually more common than an allergic etiology.

History

One should first determine whether the contact dermatitis is an allergic or an irritant phenomenon. Skin damage is usually evident within several hours of contact with a strong irritant. Weaker irritants, however, may require multiple applications days before the development of dermatitis. Allergic contact dermatitis usually appears 24 to 48 hours after exposure, before the development of clinical disease. Occasionally, the dermatitis may develop as soon as 8 to 12 hours after contact or may be delayed as long as 4 to 7 days. The history of a precipitating contactant may be either obvious or obscure. Detailed history of occupation, hygienic habits, and hobbies is frequently necessary to find the contactant.

Causes of allergic contact dermatitis:

- 1.

Poison ivy or oak

- 2.

Cosmetics/personal care products

- 3.

Nickel

- 4.

Rubber compounds

- 5.

Topical medications

Poison ivy or oak is a frequent cause of allergic contact dermatitis in the summer ( Fig. 8.4 ). The sensitizing allergens are pentadecylcatechol and heptadecylcatechol chemicals located in the sap (urushiol) of the plant. Another familiar member of this family of poisonous plants is poison sumac . Less frequently recognized family members are cashew, mango, and lacquer trees. Sensitization to poison ivy results in sensitivity to the other poisonous plants in this family. The characteristic eruption resulting from contact with poison ivy or oak is manifested by linear streaks of papules and vesicles along with cellulitic appearing plaques and patches. Contact with the smoke of burning plants can result in confluent severe dermatitis of the exposed skin.

Streaks of vesicles are characteristic of contact dermatitis to poison ivy or oak.

Cosmetics (personal care products) contain fragrances and preservatives that cause allergic contact dermatitis, particularly affecting the faces of women from the use of make-up and moisturizers, for example. Paraphenylenediamine is a dye found in permanent hair coloring. Sensitization to paraphenylenediamine occurs in hairdressers and in clients who have their hair colored. When completely oxidized, as the dye on a fur coat, paraphenylenediamine is not allergenic.

Nickel sensitivity is seen most often in women as a result of wearing “cheap” pierced earrings. It is found in many metal alloys ( Fig. 8.5 ). One cannot be certain that the commonly advertised “hypoallergenic” earrings are nickel-free. Although stainless steel contains nickel, it is bound so tightly that it usually does not allow an allergic reaction to occur.

Rubber compounds are ubiquitous. Shoes and gloves are the most common sources of allergic contact dermatitis caused by these chemicals. An eczematous reaction limited to the feet or hands is typical of shoe and glove dermatitis, respectively. The most frequent rubber allergens are mercaptobenzothiazole and thiuram .

In sleuthing the causes of contact dermatitis, one must not overlook the possibility of a topical medication perpetuating or exacerbating a preexisting dermatitis. Neomycin and bacitracin , found in topical antibiotic preparations, cause allergic contact dermatitis when these agents are used to treat cuts and abrasions, chronic ulcers, and surgical wounds.

Physical Examination

Contact dermatitis may be acute or chronic. The configuration of the lesions depends on the nature of the exposure, which may result in patches or plaques with angular corners, geometric outlines, and sharp margins. Poison ivy or oak characteristically causes linear streaks of papulovesicles.

The location of the dermatitis is helpful in predicting the causative irritant or allergen. The head and neck are frequent sites of contact dermatitis from fragrances and preservatives found in cosmetics. Hair dyes, permanent wave solutions, and shampoos produce dermatitis on the scalp. Eczema of the eyelids is caused by eye cosmetics or allergens that have been transferred from the hands, such as nail polish. Photoallergic contact dermatitis from sunscreens is produced by a photoreaction between sunlight and an allergen in exposed areas of the skin, such as the head, neck, V-shaped area of the chest, and arms. The hands are the most common area of contact dermatitis from industrial chemicals, particularly an irritant reaction from detergents, petroleum products, and solvents. Dermatitis of the feet is produced by allergens in shoes, such as rubber chemicals and leather tanning agents. The groin and buttocks in infants are frequently affected by diaper dermatitis ( Fig. 8.6 ). This condition is an irritant contact dermatitis from moisture and feces. Diaper dermatitis is often complicated by secondary infection with bacteria and yeast.

The location of the dermatitis often provides a clue to the nature of the contactant.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree