Disorders of the Subcutis

|

The reactions in the subcutis are mostly inflammatory, although tumors of the subcutis do occur. Pathologic conditions arising in the dermis may extend to the subcutis. The conditions can be classified according to their septal or lobular location, and the presence or absence of vasculitis (1). Even though all panniculitides are somewhat mixed because the inflammatory infiltrate involves both the septa and lobules, the differential diagnosis between a mostly septal and a mostly lobular panniculitis is usually straightforward at scanning magnification (2). A recent report described clinical overlap and the significance of biopsy findings in a series of 55 panniculitis cases from Saudi Arabia. A definite panniculitis diagnosis was made in 53 cases including erythema nodosum (28 cases), leukocytoclastic vasculitis (seven cases), nodular vasculitis (four cases), superficial thrombophlebitis (two cases), eosinophilic panniculitis (three cases), infection-related panniculitis (five cases), and one case each of erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), lupus panniculitis, pancreatic fat necrosis and acne conglobata with two cases remaining unclassified. Histologically, “predominantly septal” and “mixed panniculitis” were the chief inflammatory patterns in erythema nodosum cases, while mixed panniculitis was seen in most leukocytoclastic vasculitis cases and predominantly lobular and mixed panniculitis in nodular vasculitis cases (3).

VIIIA Subcutaneous Vasculitis and Vasculopathy (Septal or Lobular)

True vasculitis is defined by the presence of necrosis and inflammation in vessel walls. Other forms of vasculopathy include thrombosis and thrombophlebitis, fibrointimal hyperplasia, calcification, and neoplastic infiltration of vessel walls.

Neutrophilic Vasculitis

Lymphocytic “Vasculitis”

Granulomatous “Vasculitis”

VIIIA1 Neutrophilic Vasculitis

Neutrophils and disrupted nuclei are present in the wall of the vessel, with associated eosinophilic “fibrinoid” necrosis.

Cutaneous/Subcutaneous Polyarteritis Nodosa (See Also VB3)

Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis involving arteries and arterioles of the septa of the dermis or subcutaneous fat with few or relatively minor systemic manifestations, such as fever, malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, and neuropathy. Cutaneous vasculitis may present as a component of systemic vasculitic syndromes such as rheumatoid vasculitis or anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated primary vasculitic syndromes, which include Wegener granulomatosis, Churg–Strauss syndrome, microscopic polyangiitis, and may have overlapping histology (4). Systemic polyarteritis nodosa frequently may present first in the skin, and demonstration of multi-organ involvement, particularly in the kidneys, heart, and liver, is necessary to make the distinction. As recently reviewed, a biopsy diagnosis of vasculitis must be correlated with clinical history, physical and laboratory findings and/or angiographic features to arrive at specific diagnosis (5). Diagnosis of any individual case therefore depends on clinicopathologic correlation (6). Vasculitis extending deep into the reticular dermis or subcutaneous tissue seems to be associated more often with systemic disease such as malignancy or connective tissue disease (7). A recent review has emphasized the importance of distinguishing between superficial thrombophlebitis and arteritis. Veins in the lower legs may have a compact concentric smooth

muscle pattern with a round lumen and an intimal elastic fiber proliferation that may mimic the characteristic features of arteries; however, elastic fibers are prominent between the bundles of smooth muscle in vein walls, while being sparse in the medial muscular layer in arteries (8).

muscle pattern with a round lumen and an intimal elastic fiber proliferation that may mimic the characteristic features of arteries; however, elastic fibers are prominent between the bundles of smooth muscle in vein walls, while being sparse in the medial muscular layer in arteries (8).

Fig. VIIIA1.b. Subcutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, medium power. This medium-sized artery shows extensive infiltration and destruction of the vessel by a neutrophilic infiltrate. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

leukocytoclastic vasculitis

subcutaneous polyarteritis nodosa

superficial migratory thrombophlebitis

erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL)

VIIIA2 Lymphocytic “Vasculitis”

The concept of “lymphocytic vasculitis” is a controversial one. Many disorders characterized by lymphocytes within the walls of vessels are best classified as lymphocytic infiltrates. The term “vasculitis” may be appropriate when there is vessel wall damage, as in nodular vasculitis, even in the absence of neutrophils and “fibrinoid” changes (9).

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

nodular vasculitis

perniosis (see VB2)

angiocentric lymphomas

VIIIA3 Granulomatous “Vasculitis”

The inflammatory infiltrate in the vessel walls is composed of mixed cells including more or less epithelioid histiocytes, and giant cells. Other cell types including lymphocytes and plasma cells, and sometimes neutrophils and eosinophils, are also commonly present.

Erythema Induratum (Nodular Vasculitis)

Clinical Summary

The lesions of erythema induratum (10), also known as “nodular vasculitis,” consist of painless but somewhat tender, deep-seated, circumscribed, nodular, subcutaneous infiltrations of the lower legs, especially on the calves. Gradually, the infiltrations extend toward the surface, forming blue-red plaques that can ulcerate before healing with atrophy and scarring. Recurrences are common and often are precipitated by the onset of cold weather. Women are more commonly affected than men. Many cases are associated with detectable sequences of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in lesional tissue by PCR, with a prevalence that varies geographically, perhaps related to the prevalence of tuberculosis in the community (11,12). “Nodular vasculitis” has been proposed as a term for those cases with erythema induratum-like lesions that were not associated with tuberculosis.

Histopathology

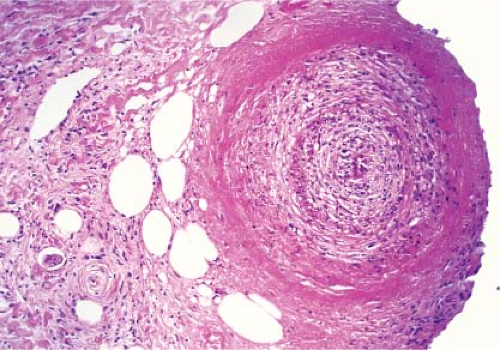

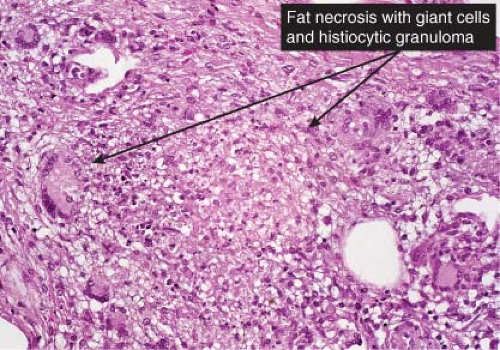

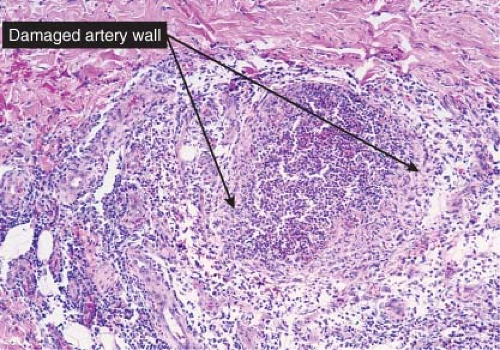

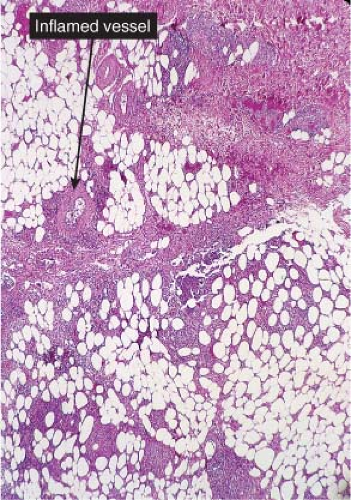

In contrast to erythema nodosum that is mainly a septal panniculitis, erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis) initially is mainly a lobular panniculitis characterized by inflammation and necrosis of the fat lobule with relatively less involvement of the structures of the septa. It is controversial whether vasculitis should be required as a necessary diagnostic feature, but nevertheless some form of vasculitis is present in most cases (13). The fat necrosis elicits granulomatous inflammation. Epithelioid cells and giant cells and/or lymphocytes and plasma cells form broad zones of inflammation surrounding the necrosis and extending between the fat cells but also can form well-delimited granulomas of the tuberculoid type. Ziehl–Neelsen stains are negative for mycobacteria. Vascular

changes are typically extensive and severe. The walls of small- and medium-sized arteries and veins are infiltrated by a dense lymphoid or granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, associated with endothelial swelling and edema of the vessel walls, fibrous thickening of the intima and, often, thrombosis of the lumen. Compromise of the lumen produces ischemic and caseous fat necrosis, which when extensive may lead to involvement of the overlying dermis and ulceration. In the necrotic fat there may be fat cysts, with surrounding amorphous, finely granular, eosinophilic material containing some pyknotic nuclei. Later lesions contain many foamy histiocytes surrounding the areas of fat necrosis.

changes are typically extensive and severe. The walls of small- and medium-sized arteries and veins are infiltrated by a dense lymphoid or granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, associated with endothelial swelling and edema of the vessel walls, fibrous thickening of the intima and, often, thrombosis of the lumen. Compromise of the lumen produces ischemic and caseous fat necrosis, which when extensive may lead to involvement of the overlying dermis and ulceration. In the necrotic fat there may be fat cysts, with surrounding amorphous, finely granular, eosinophilic material containing some pyknotic nuclei. Later lesions contain many foamy histiocytes surrounding the areas of fat necrosis.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

erythema induratum/nodular vasculitis

ENL (Type 2 leprosy reaction)

Wegener’s granulomatosis

Churg–Strauss vasculitis

Crohn’s disease

giant cell arteritis

Clin. Fig. VIIIA3. Erythema induratum. A young female presented with a tender ulcerated nodule in the left pretibial area. Cultures for tuberculosis were negative. |

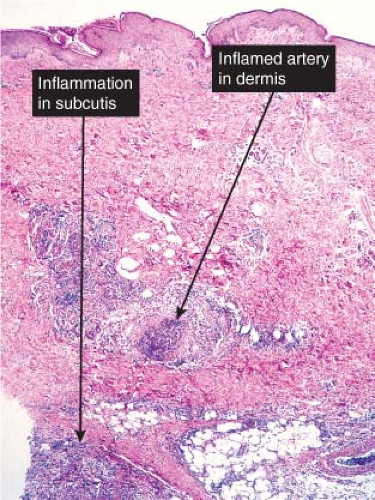

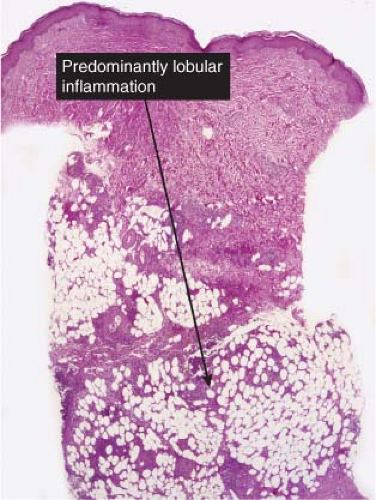

Fig. VIIIA3.a. Erythema induratum/nodular vasculitis, low power. There is inflammation involving the subcutaneous lobules with little or no inflammation in the overlying epidermis and dermis. |

Fig. VIIIA3.b. Erythema induratum/nodular vasculitis, medium power. This is a predominantly lobular panniculitis with less intense involvement of the subcutaneous septae. |

VIIIB Septal Panniculitis Without Vasculitis

The inflammation is mainly confined to the septa, although there may be some lobular involvement.

Septal Panniculitis, Lymphocytes, and Mixed Infiltrates

Septal Panniculitis, Granulomatous

Septal Panniculitis, Sclerotic

VIIIB1 Septal Panniculitis, Lymphocytes, and Mixed Infiltrates

The inflammation predominantly involves the subcutaneous septa, although there may be “spillover” into the fat lobules. The infiltrate is mainly lymphocytic although other cells can be found including plasma cells and acute inflammatory cells.

Erythema Nodosum

Clinical Summary

Although the causes of erythema nodosum (14,15) are multiple and cannot always be determined, streptococcal infection is the most common. In the acute form of erythema nodosum, there is a sudden appearance of tender, bright red or dusky red-purple nodules that only slightly elevate the level of the skin surface and have a strong predilection for the anterior surfaces of the lower legs, although they also may occur elsewhere, but mostly on dependent regions. The lesions do not ulcerate and generally involute within a few weeks, while new lesions may intermittently appear for several months. The lesions are tender and warm, and the acute disease is often accompanied by fever, malaise, leukocytosis, and arthropathy. Focal hemorrhages are common and can cause the lesions to resemble bruises (erythema contusiforme). The chronic form of erythema nodosum may last from a few months to a few years and is also known as erythema nodosum migrans or subacute nodular migratory panniculitis. There are one or several red, slightly tender subcutaneous nodules that are found, usually unilaterally, on the lower leg. Most of the patients are women with a solitary lesion and a recent history of sore throat and arthralgia. The nodules enlarge by peripheral extension into plaques, often with central clearing.

Histopathology

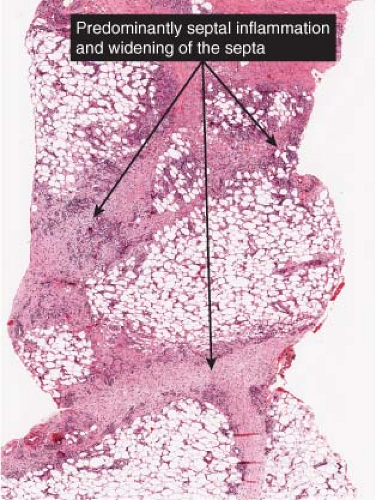

In early acute lesions there is edema of the subcutaneous septa with a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, having a slight admixture of neutrophils and eosinophils. Focal fibrin deposition and extravasation of erythrocytes occur frequently. Often the inflammation is most intense at the periphery of the edematous septa and extends into the periphery of the fat lobules between individual fat cells in a lace-like fashion without prominent necrosis of the fat. Clusters of macrophages around small blood vessels, or a slit-like space, occur in early lesions and are known as Miescher’s radial nodules. The degree of vascular involvement is variable, but usually falls short of true vasculitis. Later acute lesions show widening of the septa, often with fibrosis and with inflammation at the periphery of the fat lobules. Neutrophils usually are absent and there are more macrophages in the infiltrate. Macrophages at the edges of the fat lobules have a “foam-cell” appearance from phagocytozed lipid. Loosely formed granulomas comprised of macrophages and giant cells, without lipid deposition, are more frequent in late lesions compared to the early ones. The oldest lesions have septal widening and fibrosis

with a decrease in all of the inflammatory cells, except for a few persisting at the periphery of the fat lobules.

with a decrease in all of the inflammatory cells, except for a few persisting at the periphery of the fat lobules.

Clin. Fig. VIIIB1. Erythema nodosum. Tender erythematous nodules on the shins is a classic presentation. |

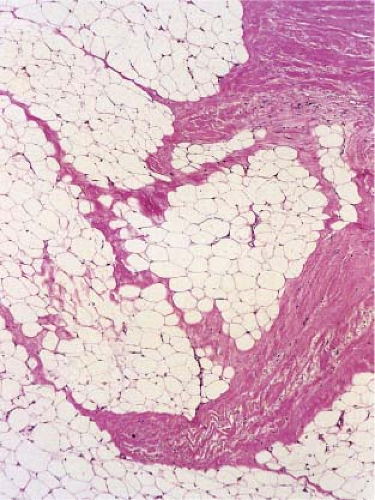

Fig. VIIIB1.a. Erythema nodosum, low power. Scanning magnification reveals thickening of the fibrous septa. |

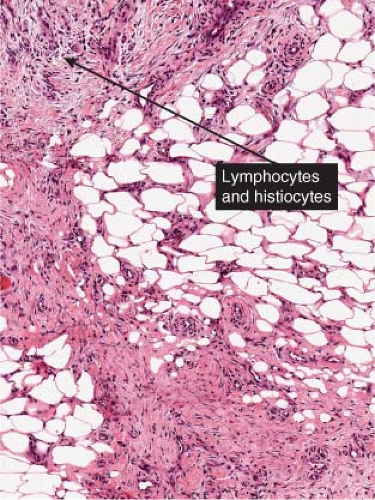

Fig. VIIIB1.d. Erythema nodosum, high power. Lymphocytes and histiocytes are present in the expanded septa. |

Fig. VIIIB1.e. Erythema nodosum, high power. Giant cells, lymphocytes, and occasionally eosinophils and neutrophils may also be present. |

In chronic erythema nodosum, the histologic findings are generally the same as those of the late stages of acute erythema nodosum. However, granuloma and lipogranuloma formation often is more pronounced. There is vascular proliferation and thickening of the endothelium with extravasation of erythrocytes.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

erythema nodosum and variants

Crohn’s disease

morphea

VIIIB2 Septal Panniculitis, Granulomatous

Subcutaneous granulomas may present as ill-defined collections of epithelioid histiocytes, as well-formed epithelioid-cell granulomas, and as palisading granulomas in which histiocytes are radially arranged around areas of necrosis or necrobiosis. Most of the conditions in this list may also present as mixed lobular/septal panniculitis (see VIIIC5).

Subcutaneous Granuloma Annulare

Clinical Summary

In this disorder, subcutaneous nodules occur, especially in children, either alone or in association with intradermal lesions (16). The subcutaneous nodules clinically resemble rheumatoid nodules, although there is a greater tendency to occur on the legs and feet, and there is no history of arthritis. A very rare, deep, destructive form of granuloma annulare has also been described. This lesion might also be considered in the section on mixed septal and lobular involvement (see VIIID6).

Histopathology

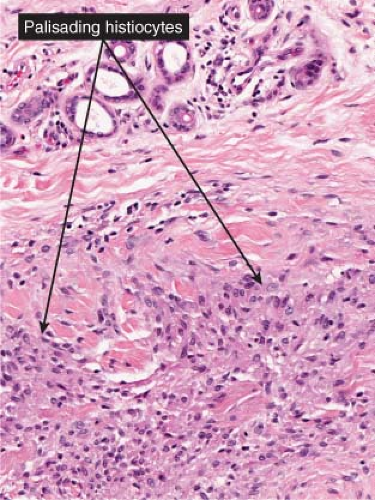

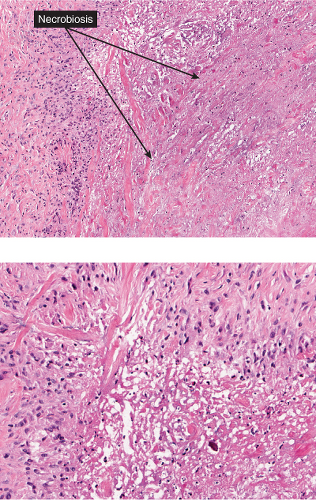

The subcutaneous nodules of granuloma annulare usually show large foci of palisaded histiocytes surrounding areas of degenerated collagen and prominent mucin with a pale appearance; however, biopsies in which mucin was not apparent or the central area

appeared more fibrinoid have also been reported. The histopathologic differential diagnosis includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, and epithelioid sarcoma (17). Especially in the pediatric population, it is important to consider subcutaneous granuloma annulare before making a diagnosis of rheumatoid nodule.

appeared more fibrinoid have also been reported. The histopathologic differential diagnosis includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, and epithelioid sarcoma (17). Especially in the pediatric population, it is important to consider subcutaneous granuloma annulare before making a diagnosis of rheumatoid nodule.

Clin. Fig. VIIIB2. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Subcutaneous nodules in an annular distribution developed on a child’s dorsal foot. |

Fig. VIIIB2.a. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare, low power. The septum of the subcutaneous fat has been replaced by inflammation and altered connective tissue. (continues) |

Fig. VIIIB2.b. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare, medium power. In the subcutaneous septum, there is palisaded granulomatous inflammation. |

Fig. VIIIB2.c,d. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare, high power. The altered (necrobiotic) collagen is surrounded by a palisade of histiocytes as well as fibrosis. |

Table VIII.1. Selected Panniculitides | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

palisaded granulomas

subcutaneous granuloma annulare

rheumatoid nodules

sarcoidosis

lichen scrofulosorum

Crohn’s disease

subcutaneous infections

syphilis

tuberculosis

VIIIB3 Septal Panniculitis, Sclerotic

Sclerosis of the panniculitis may begin as a septal process and extend into the lobules.

Scleroderma and Morphea

Clinical Summary

(See also VF1). Morphea is also known as localized scleroderma, and is differentiated from systemic sclerosis based on the absence of sclerodactyly,

Raynaud phenomenon, and nailfold capillary changes (18). Many patients with morphea have systemic manifestations, such as malaise, fatigue, arthralgias, and myalgias, and positive autoantibody serologies. The pathogenesis of morphea is not understood at this time, but ultimately results in an imbalance of collagen production and destruction.

Raynaud phenomenon, and nailfold capillary changes (18). Many patients with morphea have systemic manifestations, such as malaise, fatigue, arthralgias, and myalgias, and positive autoantibody serologies. The pathogenesis of morphea is not understood at this time, but ultimately results in an imbalance of collagen production and destruction.

Clin. Fig. VIIIB3. Morphea. This indurated plaque with an ivory color represents the plaque type of this disease. |

Histopathology

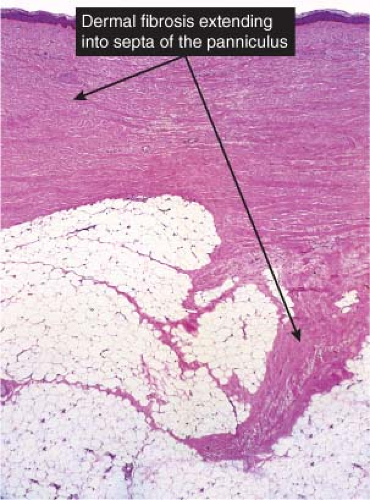

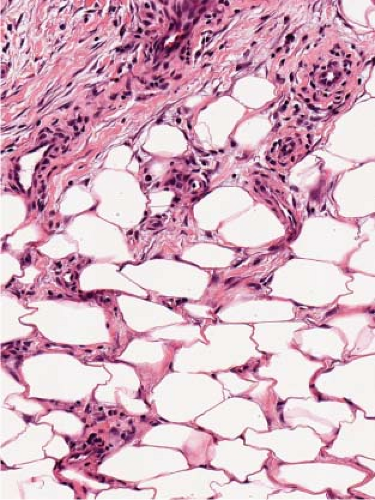

Changes in the subcutis are prominent in both scleroderma and morphea (19). The inflammatory infiltrate involving the subcutaneous fat in morphea is often much more pronounced than that in the dermis. It consists of lymphocytes and plasma cells, and extends upward toward the eccrine glands. Trabeculae subdividing the subcutaneous fat are thickened by an inflammatory infiltrate and deposition of new collagen. Large areas of subcutaneous fat are replaced by newly formed collagen composed of fine, wavy fibers. Vascular changes in the early inflammatory stage may consist of endothelial swelling and edema of the walls of the vessels. In the late sclerotic stage, as seen in the center of old morphea lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate has disappeared almost completely, except in some areas of the subcutis. The fascia and striated muscles underlying lesions of morphea may be affected in the linear, segmental, subcutaneous, and generalized types, showing fibrosis and sclerosis similar to that seen in subcutaneous tissue. The muscle fibers appear vacuolated and separated from one another by edema and focal collections of inflammatory cells. Aggregates of calcium may also be seen in the late stage within areas of sclerotic, homogeneous collagen of the subcutaneous tissue.

In early lesions of systemic scleroderma, the inflammatory reaction is less pronounced than in morphea. The vascular changes in early lesions are slight, as in morphea. In contrast, in the late stage, systemic scleroderma shows more pronounced vascular changes than morphea, particularly in the subcutis. These changes include a paucity of blood vessels, thickening and hyalinization of their walls, and narrowing of the lumen.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

scleroderma, morphea

eosinophilic fasciitis

ischemic liposclerosis

lipodermatosclerosis

toxins

VIIIC Lobular Panniculitis Without Vasculitis

The inflammation is mainly confined to the lobules, although there may be some septal involvement.

Lobular Panniculitis, Lymphocytes Predominant

Lobular Panniculitis, Lymphocytes, and Plasma Cells

Lobular Panniculitis, Neutrophilic

Lobular Panniculitis, Eosinophils Prominent

Lobular Panniculitis, Histiocytes Prominent

Lobular Panniculitis, Mixed with Foam Cells

Lobular Panniculitis, Granulomatous

Lobular Panniculitis, Crystal Deposits, Calcifications

Lobular Panniculitis, Necrosis Prominent

Lobular Panniculitis, Embryonic Fat Pattern

Lobular Panniculitis, Lipomembranous

VIIIC1 Lobular Panniculitis, Lymphocytes Predominant

Lymphocytes are the primary infiltrating cells.

Lupus Erythematosus Panniculitis

Clinical Summary

In patients with chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, the lesions can be deep and can involve the panniculus either alone or accompanied by dermal lesions (20). The patients can have either chronic discoid lupus erythematosus or systemic lupus erythematosus. Most commonly, the skin lesions are firm, indurated subcutaneous nodules and plaques that tend to involve the skin of the trunk and proximal extremities, particularly the lateral aspects of the upper arms, thighs, and buttocks. The overlying skin shows no specific changes. The lesions are painful and have a tendency to ulcerate and to heal leaving depressed scars. When the overlying skin is involved there is a loss of hair, erythema, poikiloderma, and epidermal atrophy. The patients may present with localized depressions of lipoatrophy alone. The term “lupus profundus” has been used both for lupus panniculitis and also for discoid lupus erythematosus lesions that involve the dermis and extend deeply into the subcutis.

Histopathology

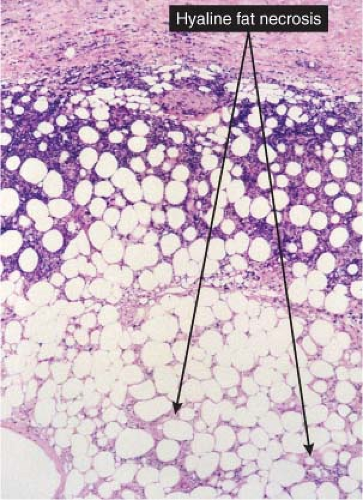

The histologic sections show a deep lymphocytic infiltrate in the fat lobules and in the septa. Lymphoid aggregates, nodules, and germinal centers are common. Usually there is mucinous edema of the septa and of the overlying dermis. The dermis can have a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with plasma cells or all of the changes of lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus may be present. A distinctive feature is the so-called “hyaline necrosis” of the fat, in which portions of the fat lobule have lost nuclear staining of the fat cells and there is an accumulation of fibrin and other proteins in a homogeneous eosinophilic matrix between residual fat cells and extracellular fat globules. Blood vessels are infiltrated by lymphoid cells and can have restriction of their lumen diameter. Calcification may be present in older lesions. The differential diagnosis includes subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. In a recent study, features helpful in making this distinction included the presence of involvement of the

epidermis, lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers, mixed cell infiltrate with prominent plasma cells, clusters of B lymphocytes, and polyclonal T cell receptor gene rearrangements (21). Monoclonal gene rearrangements have been described in rare cases, and clear distinction between these entities may require observation over time in some difficult cases (22).

epidermis, lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers, mixed cell infiltrate with prominent plasma cells, clusters of B lymphocytes, and polyclonal T cell receptor gene rearrangements (21). Monoclonal gene rearrangements have been described in rare cases, and clear distinction between these entities may require observation over time in some difficult cases (22).

Clin. Fig. VIIIC1. Lupus panniculitis. A patient with discoid lupus erythematosus developed an indurated subcutaneous area with postinflammatory hyper/hypopigmentation on the lateral thigh. |

Fig. VIIIC1.b. Lupus panniculitis, medium power. The inflammatory infiltrate outlines individual adipocytes, creating a lace-like pattern (C. Jaworsky). |

Fig. VIIIC1.c. Lupus panniculitis, high power. Foam cells indicate adipocyte injury. Note also the hyaline matrix between adipocytes (“hyaline fat necrosis”) (C. Jaworsky). |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

lupus panniculitis lupus profundus

nodular vasculitis/erythema induratum, inapparent vasculitis

post-steroid panniculitis

subcutaneous lymphoma-leukemia

VIIIC2 Lobular Panniculitis, Lymphocytes, and Plasma Cells

Lymphocytes and plasma cells are the primary infiltrating cells. These conditions are more likely to present as primarily septal or as mixed panniculitis (see VIIIB3 and VIIIC1).

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

lupus profundus

scleroderma

Fig. VIIIC2.a. Lupus panniculitis, high power. A lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate splays collagen bundles and adipocytes (see also VIIIC1) (C. Jaworsky). |

VIIIC3 Lobular Panniculitis, Neutrophilic

Lymphocytes and neutrophils are the primary infiltrating cells. The conditions listed below are more likely to present as a mixed lobular and septal panniculitis (see VIIID1)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree