Acantholytic, Vesicular, and Pustular Disorders

|

Keratinocytes may separate from each other on the basis of immunologic antigen–antibody mediated damage resulting in separation and rounding-up of keratinocyte cell bodies (acantholysis), on the basis of edema and inflammation (spongiosis), or perhaps on the basis of structural deficiencies of cell adhesion (Darier’s disease). These processes produce intra-epidermal spaces (vesicles, bullae, pustules).

IVA Subcorneal or Intracorneal Separation

There is separation within or just below the stratum corneum. Inflammatory cells may be sparse, or may consist predominantly of neutrophils.

Sub/Intracorneal Separation, Scant Inflammatory Cells

Sub/Intracorneal Separation, Neutrophils Prominent

Sub/Intracorneal Separation, Eosinophils Predominant

IVA1 Sub/Intracorneal Separation, Scant Inflammatory Cells

There is separation within or just below the stratum corneum, associated with scant inflammation, usually lymphocytic. Pemphigus foliaceus is prototypic (1,2,3).

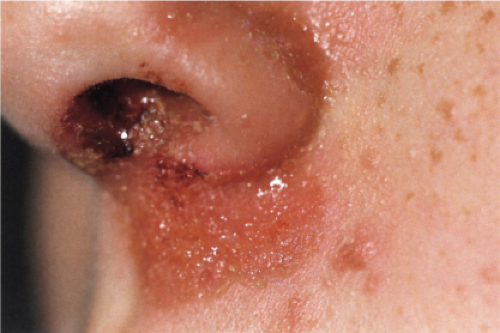

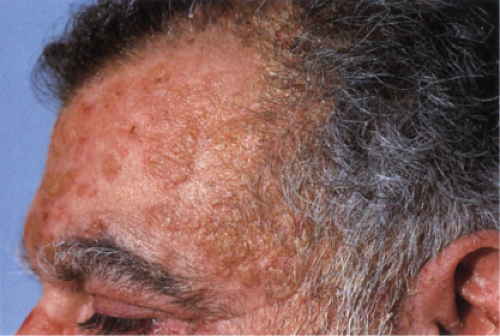

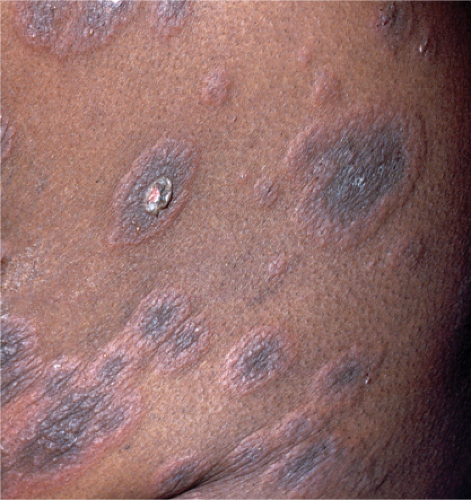

Pemphigus Foliaceus

Usually developing in middle-aged individuals, pemphigus foliaceus may have a chronic generalized course or may rarely present as an exfoliative dermatitis. The disorder is caused by autoantibodies to a desmosomal protein, desmoglein 1, causing dyshesion in the outer spinous and granular epidermal layers. Some cases may be related to exposure to drugs such as penicillamine (4). Patients present with flaccid bullae that usually arise on an erythematous base. Erythema, oozing, and crusting are present. Because of their superficial location, the blisters break easily, leaving shallow erosions rather than the denuded areas seen in pemphigus vulgaris. Oral lesions do not occur. The Nikolsky sign is positive, and Tzanck preparation reveals acantholytic granular keratinocytes. Fogo selvagem (endemic pemphigus foliaceus which occurs in Brazil) is clinically, histologically, and immunologically indistinguishable from pemphigus foliaceus.

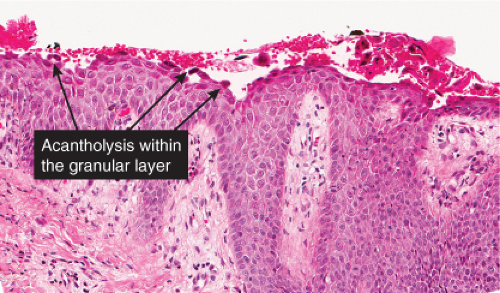

Histopathology

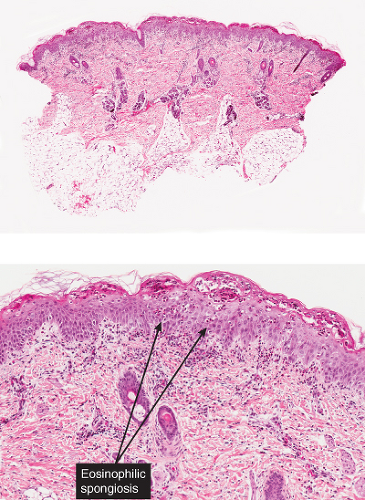

The earliest change consists of acantholysis in the upper epidermis, within or adjacent to the granular layer, leading to a subcorneal bulla in some instances, more commonly, enlargement of the cleft leads to detachment of the stratum corneum without bulla formation. The number of acantholytic keratinocytes is usually small, often requiring a careful search to identify them. Secondary clefts may develop, leading to detachment of the epidermis in its midlevel. These clefts may extend to above the basal layer, rarely giving rise to limited areas of suprabasal separation. In the setting of a subcorneal blister, dyskeratotic granular keratinocytes are diagnostic for this disorder. Eosinophilic spongiosis may be prominent with intraepidermal eosinophilic pustules. Thus the histologic features of pemphigus foliaceus may have three patterns: (1) eosinophilic spongiosis, (2) a subcorneal blister, often with few acantholytic keratinocytes, and (3) a subcorneal blister with dyskeratotic granular keratinocytes, diagnostic for this disorder. The character of the inflammatory infiltrate observed is variable. Most commonly the histologic differential diagnoses considered for pemphigus foliaceus are staphylococcal scalded skin and bullous impetigo.

Direct immunofluorescence in pemphigus foliaceus shows cell surface membrane staining with antibodies to IgG. The staining may be confined to the upper epidermal layers or it may involve all epidermal layers, indistinguishable from pemphigus vulgaris. Indirect immunofluorescence can also be utilized to detect circulating antibodies in the patient’s blood. In pemphigus foliaceus, normal human skin has a higher sensitivity as a substrate than monkey esophagus (5). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing provides a quantitative and very sensitive method for detecting serum anti-dsg-1 antibodies. Sensitivities and specificities have been reported in the range of 92% to 100% (6).

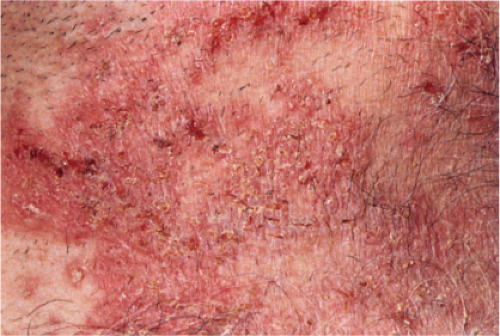

Clin. Fig. IVA1. Pemphigus foliaceus. A middle-aged male with crusted plaques required systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy to control his blistering disease. (W. Witmer). |

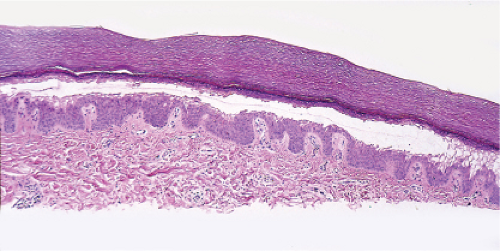

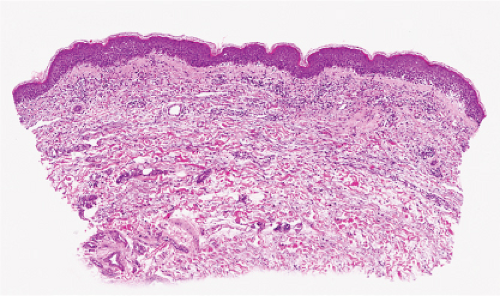

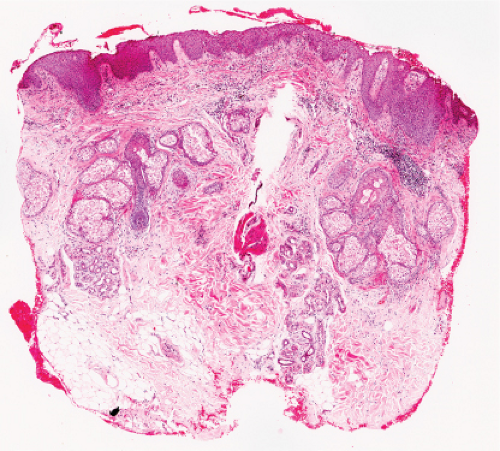

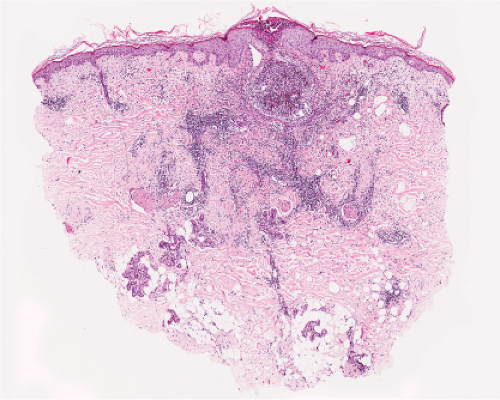

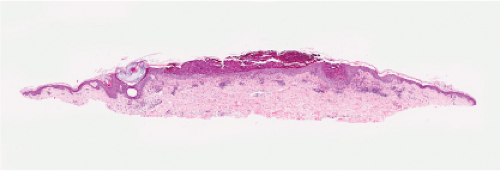

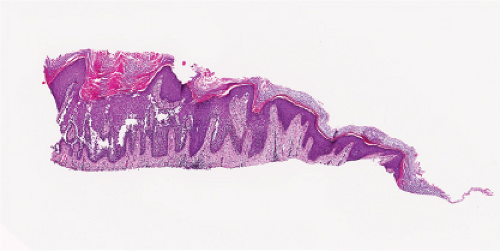

Fig. IVA1.a. Pemphigus foliaceus, low power. A blister forms in the superficial epidermis and there is a sparse dermal infiltrate. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

staphylococcal scalded skin

bullous impetigo

miliaria crystallina

exfoliative dermatitis

pemphigus foliaceus

pemphigus erythematosus

necrolytic migratory erythema

pellagra

acrodermatitis enteropathica

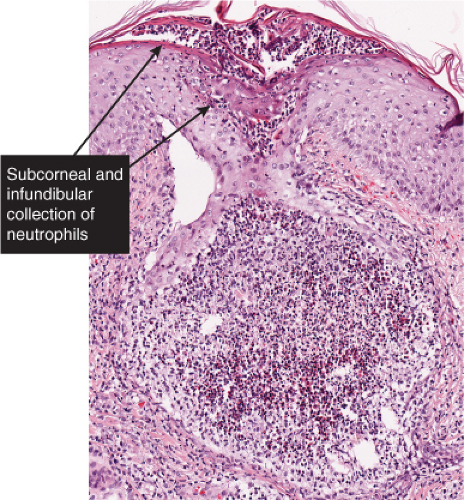

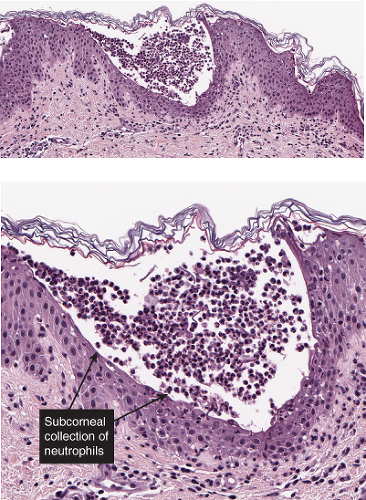

IVA2 Sub/Intracorneal Separation, Neutrophils Prominent

There is separation in or just below the stratum corneum. Neutrophils are prominent in the stratum corneum and in the superficial epidermis, and can often be found in the dermis. Impetigo contagiosa is a prototypic example (7,8).

Impetigo Contagiosa

Clinical Summary

Impetigo contagiosa is primarily an endemic disease in preschool-age children, which may occur in epidemics. Very early lesions consist of vesicopustules that rupture quickly and are followed by heavy, yellow crusts. Most of the lesions are located in exposed areas. An occasional sequela is acute glomerulonephritis, which usually has a favorable long-term prognosis.

Impetigo contagiosa is clinically and histologically distinct from Staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome (Ritter’s disease), which occurs largely in the newborn and in children younger than 5 years, and rarely in older individuals often in association with immunodeficiency or renal

insufficiency, and from bullous impetigo (9). The disease begins abruptly with diffuse erythema and fever. Large, flaccid bullae filled with clear fluid form and rupture almost immediately. Large sheets of superficial epidermis separate and exfoliate. The disease is rarely fatal in children. In neonates with generalized lesions, and in adults with severe underlying diseases, the prognosis is worse. Both bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome are transmissible and can cause epidemics in nurseries, where they may occur together. The blisters in bullous impetigo and the scalded-skin syndrome are caused by exfoliative toxin (exfoliatin, types A or B) released by staphylococcus. In patients with bullous impetigo, the toxin produces blisters locally at the site of infection, whereas in cases of the scalded-skin syndrome, it circulates throughout the body, causing blisters at sites distant from the infection (3). In these two conditions, the bullae contain only few inflammatory cells, whereas in impetigo contagiosa, the blisters are filled with neutrophils.

insufficiency, and from bullous impetigo (9). The disease begins abruptly with diffuse erythema and fever. Large, flaccid bullae filled with clear fluid form and rupture almost immediately. Large sheets of superficial epidermis separate and exfoliate. The disease is rarely fatal in children. In neonates with generalized lesions, and in adults with severe underlying diseases, the prognosis is worse. Both bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome are transmissible and can cause epidemics in nurseries, where they may occur together. The blisters in bullous impetigo and the scalded-skin syndrome are caused by exfoliative toxin (exfoliatin, types A or B) released by staphylococcus. In patients with bullous impetigo, the toxin produces blisters locally at the site of infection, whereas in cases of the scalded-skin syndrome, it circulates throughout the body, causing blisters at sites distant from the infection (3). In these two conditions, the bullae contain only few inflammatory cells, whereas in impetigo contagiosa, the blisters are filled with neutrophils.

An important difference between the two diseases is that no staphylococci can be grown from the bullae of the staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome, in contrast to those of bullous impetigo. In staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome, the staphylococci are present at a distant focus, often a purulent conjunctivitis, rhinitis, or pharyngitis or rarely a cutaneous infection or a septicemia.

Histopathology

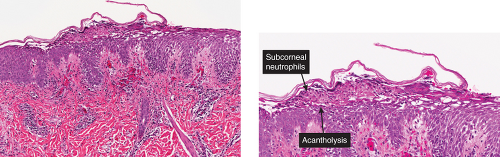

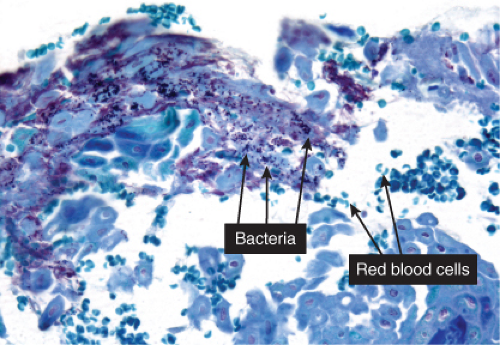

The vesicopustule of impetigo contagiosa arises in the upper layers of the epidermis above, within, or below the granular layer. It contains numerous neutrophils. Not infrequently, a few acantholytic cells can be observed at the floor of the vesicopustule. Often,

Gram-positive cocci are present, both within neutrophils and extracellularly. The stratum malpighii underlying the bulla is spongiotic, and neutrophils often can be seen migrating through it. The upper dermis contains a moderately severe inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils and lymphoid cells. At a later stage, when the bulla has ruptured, the horny layer is absent, and a crust composed of serous exudate and the nuclear debris of neutrophils may be seen covering the stratum malpighii.

Gram-positive cocci are present, both within neutrophils and extracellularly. The stratum malpighii underlying the bulla is spongiotic, and neutrophils often can be seen migrating through it. The upper dermis contains a moderately severe inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils and lymphoid cells. At a later stage, when the bulla has ruptured, the horny layer is absent, and a crust composed of serous exudate and the nuclear debris of neutrophils may be seen covering the stratum malpighii.

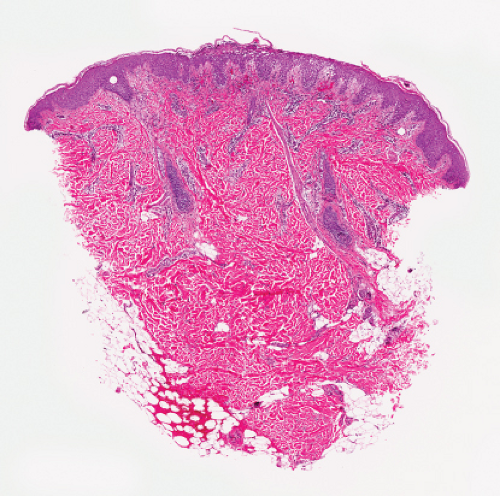

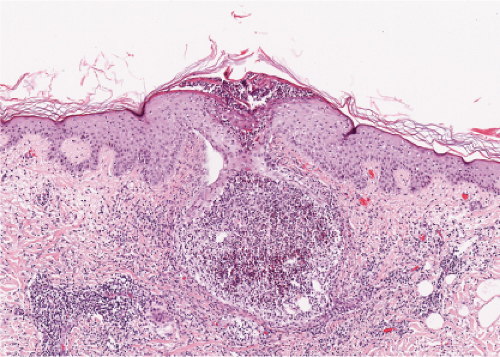

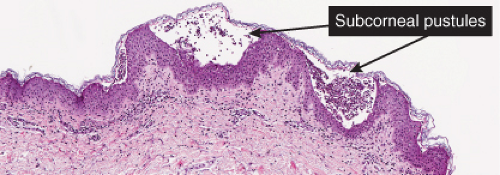

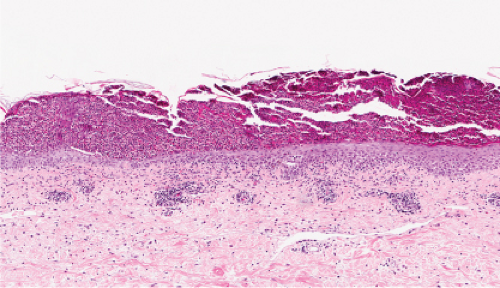

Fig. IVA2.a. Impetigo contagiosa, medium power. Neutrophils are seen in the upper epidermis, forming a subcorneal pustule. There is a superficial mixed infiltrate within the dermis. |

Figs. IVA2.b and c. Impetigo contagiosa, low and high power. The subcorneal blister is filled with neutrophils. The stratum corneum is thickened and crusted. |

Fig. IVA2.d. Impetigo contagiosa, high power. Gram stain demonstrates bacterial colonies within the stratum corneum. |

In both bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome, the cleavage plane of the bulla, like that in impetigo contagiosa, lies in the uppermost epidermis either below or, less commonly, within the granular layer. A few acantholytic cells are often seen adjoining the cleavage plane. In contrast to impetigo contagiosa, however, there are few or no inflammatory cells within the bulla cavity. In bullous impetigo, the upper dermis may show a polymorphous infiltrate, whereas in the staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome the dermis is usually free of inflammation.

Folliculitis with Subcorneal Pustule Formation

A superficial biopsy of folliculitis could mimic a subcorneal pustule.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

Clinical Features

The majority of these cases have been associated with medications and may have previously been called pustular drug eruption. (see also Section IVB.3). Various drugs are implicated in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) (10). Widespread non-follicular, sterile, pustules develop within a period of hours after administration of the offending agent. Although enteroviral infection and mercury exposure are cited as causes, antibacterial antibiotics are most often implicated with a broad range of other medications as well, including acetaminophen and terbinafine. The involvement of drug-specific T cells in the pathogenesis can be confirmed by positive skin patch

tests and lymphocyte transformation tests. Fever, leukocytosis, purpura, and occasionally clinical features suggesting erythema multiforme accompany the pustules. In vitro studies have shown this to be a drug-specific process effected by CD4+ T-cell mediated release of the neutrophil chemoattractant, IL-8 (11).

tests and lymphocyte transformation tests. Fever, leukocytosis, purpura, and occasionally clinical features suggesting erythema multiforme accompany the pustules. In vitro studies have shown this to be a drug-specific process effected by CD4+ T-cell mediated release of the neutrophil chemoattractant, IL-8 (11).

Fig. IVA2.e. Folliculitis with subcorneal pustule formation, low power. There is an intense, neutrophil-rich infiltrate which has obliterated the hair follicle. (J. Junkins-Hopkins). |

Fig. IVA2.f. Folliculitis with subcorneal pustule formation, low power. There is a mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis around the follicle. |

Histopathology

Biopsies show subcorneal or intraepidermal pustules, papillary dermal edema, and a lymphohistiocytic perivascular infiltrate with some eosinophils and neutrophils. Vasculitis and/or single-cell keratinocyte necrosis may be present.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

impetigo contagiosa

bullous impetigo

epidermis adjacent to folliculitis

impetiginized dermatitis

candidiasis

subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon–Wilkinson)

pustular psoriasis

IgA pemphigus

secondary syphilis

acropustulosis of infancy

transient neonatal pustular melanosis

Fig. IVA2.h. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, medium power. A subcorneal separation is seen associated with a superficial dermal infiltrate in which neutrophils are present. |

Fig. IVA2.k. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, high power. Neutrophils and lymphocytes are present in the dermal infiltrate. |

Table IV.1. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis, Pustular Psoriasis (von Zumbusch), Subcorneal Pustular Dermatosis (Sneddon–Wilkinson) and Bullous Impetigo Compared (11) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

IVA3 Sub/Intracorneal Separation, Eosinophils Predominant

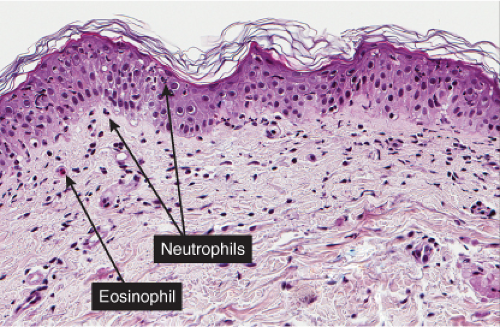

There is separation in or just below the stratum corneum, with (pemphigus) or without acantholytic keratinocytes. Eosinophils are present in the epidermis, and occasionally there is eosinophilic spongiosis. The separation is associated with a dermal infiltrate that contains eosinophils. Erythema toxicum neonatorum is a prototypic example (12), which however is rarely biopsied.

Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum

Clinical Summary

A benign, asymptomatic eruption affecting about 40% of term infants usually within 12 to 48 hours after birth, erythema toxicum lasts 2 to 3 days and consists of blotchy macular erythema, papules, and pustules that tend to develop at sites of pressure. The eruption is associated with blood eosinophilia.

Histopathology

The macular erythema is characterized by sparse eosinophils in the upper dermis, largely in a perivascular location, and mild papillary dermal edema. The papules show an accumulation of numerous eosinophils and some neutrophils in the area of a hair follicle and the overlying epidermis. Papillary dermal edema is more intense and eosinophils, more numerous. Mature pustules are subcorneal and are filled with eosinophils and occasional neutrophils. The pustules form as a result of the upward migration of eosinophils to the surface epidermis from within and around hair follicles.

Differential Diagnosis

The subcorneal pustules of impetigo and transient neonatal pustular melanosis are not follicular in origin and contain neutrophils rather than eosinophils. Although many eosinophils are present in the vesicles of incontinentia pigmenti, the vesicle is intraepidermal rather than subcorneal, and spongiosis is present. In addition, necrotic keratinocytes may be prominent in incontinentia pigmenti but are absent in erythema toxicum neonatorum.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

erythema toxicum neonatorum

pemphigus foliaceus

pemphigus erythematosus

IgA pemphigus

eosinophilic pustular folliculitis

incontinentia pigmenti, vesicular

exfoliative dermatitis, drug induced

scabies

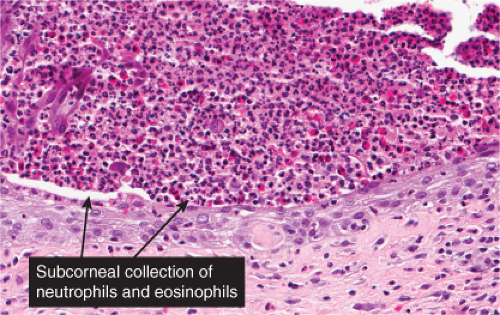

Fig. IVA3.a. Subcorneal pustule with eosinophils. There is a broad lesion characterized by increased cells in the stratum corneum with crust formation. |

Fig. IVA3.b. Subcorneal pustule with eosinophils. Subcorneal pustule and a mixed cell infiltrate in the superficial dermis. |

Scabies with Eosinophilic Pustulosis

An elderly patient with scabies had these unusual biopsy findings (Figs. IVA3.a,c). In an appropriate setting, the differential diagnosis could include erythema toxicum neonatorum.

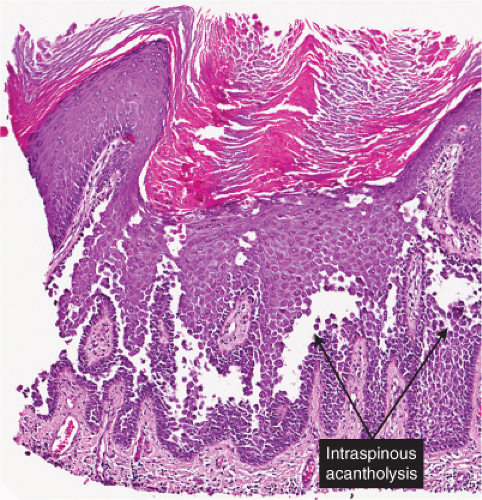

IVB Intraspinous Keratinocyte Separation, Spongiotic

There are spaces within the epidermis (vesicles, bullae). There may be dyskeratosis or acantholysis, and a few eosinophils may be present in the epidermis.

1. Intraspinous Spongiosis, Scant Inflammatory Cells

2. Intraspinous Spongiosis, Lymphocytes Predominant

2a. Intraspinous Spongiosis, Eosinophils Present

3. Intraspinous Spongiosis, Neutrophils Predominant

IVB1 Intraspinous Spongiosis, Scant Inflammatory Cells

The infiltrate in the dermis is scant, lymphocytic, or eosinophilic. Transient acantholytic dermatosis is prototypic.

Friction Blister

Clinical Summary

Friction blisters are caused by mechanical shearing forces, resulting in disruption to keratinocytes or cytolysis. This occurs in the normal epidermis when the structural (keratin) matrix of the keratinocyte is overwhelmed by high levels of physical agents such as friction and heat. Friction (mechanical energy applied parallel to the epidermis) leads to the shearing of keratinocytes one from another and of the keratinocytes themselves, typically at the level of the stratum spinosum, giving the characteristic clear, fluid-filled blisters. The area of the separation fills due to hydrostatic pressure with a clear transudate with a low protein level. At about 24 hours, there is high mitotic activity in the basal cells; at 48 and 120 hours, new stratum granulosum and stratum corneum, respectively, can be seen (13). Minimal friction may lead to cytolysis in subjects whose keratinocytes do not have a normal structural matrix, such as in epidermolysis bullosa.

Histopathology

Usual friction blisters show evidence of initial spongiosis and then disruption of the keratinocytes in the spinous layer. In lesions of the palms or soles, the blisters remain intact for a time because of the thick stratum corneum in these sites.

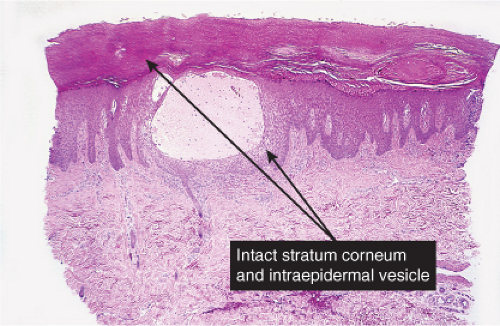

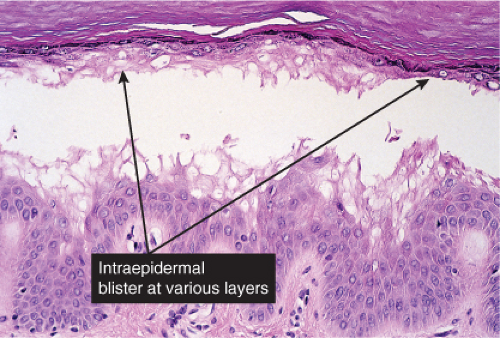

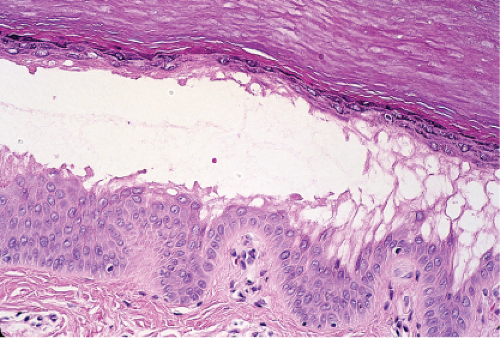

Fig. IVB1.b. Friction blister, medium power. The blister is formed by cytolysis of keratinocytes with spongiotic edema, but there is scant associated inflammation. |

Fig. IVB1.c. Friction blister, medium power. There may be evidence of damage to the surface epithelium, or it may be relatively intact, especially on the palms or soles as in this example. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

dyskeratosis

epidermolytic hyperkeratosis

epidermolytic acanthoma

miliaria rubra

transient acantholytic dermatosis

bullous dermatitis of diabetes and of uremia

coma bulla

friction blisters

IVB2 Intraspinous Spongiosis, Lymphocytes Predominant

In the dermis, lymphocytes predominate. Eosinophils can be found in most examples of atopy, and in allergic contact dermatitis. The clinical manifestation of spongiotic dermatitis (a histologic pattern) is eczematous dermatitis. This is a T-cell-mediated inflammatory skin disease, where activated T cells may harm epidermal keratinocytes by direct cell–cell contact mediated cytotoxicity or by secreted proinflammatory cytokines, accounting for at least some of the features of intercellular edema or spongiosis formation. It has been shown that activated T cells infiltrating the skin induce apoptosis of single keratinocytes, as shown in situ, and in the lesional skin of atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. Interestingly, in these studies, apoptosis of single keratinocytes was detected predominantly in suprabasal epidermal layers, concomitant with the predominantly observed suprabasal spongiosis formation in these conditions. This may be due to the existence of anti-apoptosis programs predominantly in basal keratinocytes (14).

Dyshidrotic Dermatitis (Eczema)

Clinical Summary

This entity is characterized by recurrent, severely pruritic, deep-seated vesicles that classically involve the lateral aspects of the fingers and, in some cases, the toes. Emotional stress may exacerbate the eruption. In chronic cases, there may be more extensive involvement of the palms and soles. Although the eruption develops acutely, it may become chronic with erythema, lichenification, and fissuring. Secondary impetiginization (bacterial infection with neutrophils in the stratum corneum) is common.

Histopathology

Spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation occur in acute lesions. There is a superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with exocytosis of lymphocytes into spongiotic zones. The infiltration is usually mild. In acute lesions, the compact, thickened stratum corneum of acral skin remains intact, and the epidermal thickness is normal. With chronicity, spongiosis diminishes, acanthosis and parakeratosis predominate, and serum may be identified within the stratum corneum. Difficulty in diagnosis may occur because of the formation of vesiculopustules in older lesions.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

spongiotic (eczematous) dermatitis (see Section IIIB.1)

atopic dermatitis

allergic contact dermatitis

photoallergic drug eruption

irritant contact dermatitis

nummular eczema

dyshidrotic dermatitis

“id” reaction

seborrheic dermatitis

stasis dermatitis

miliaria rubra

pityriasis rosea

IVB2a Intraspinous Spongiosis, Eosinophils Present

The number of eosinophils seen is variable from many in incontinentia pigmenti and pemphigus vegetans to few in atopic dermatitis. Eosinophilic spongiosis is a histopathologic reaction pattern that is a finding common in certain inflammatory skin diseases, including spongiotic dermatitis, arthropod bite reactions and scabies, occasionally viral vesicular disorders, incontinentia pigmenti, and immunobullous disorders, including especially bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus, and related disorders. Eosinophilic spongiosis can also be encountered occasionally in a variety of other unrelated disorders, including polycythemia vera, porokeratosis, and Meyerson’s “inflammatory nevi.” Although intraepithelial eosinophils can be found in biopsies of follicular disorders, such as Ofuji’s disease or eosinophilic folliculitis, the term eosinophilic spongiosis is reserved for cases with eosinophils present in spongiotic areas of the epidermis (15).

Bullous Pemphigoid, Urticarial Phase (See also Section IVE3)

Clin. Fig. IVB2a.a. Bullous pemphigoid. Pruritic, urticarial plaques on the trunk often herald the diagnosis of this blistering disease most often seen in elderly persons. |

Incontinentia Pigmenti

Clinical Summary

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominantly inherited disorder. Males with the abnormal gene on their single X chromosome are hemizygous for this condition and hence are so severely affected that they usually die in utero. The familial form of this disorder IP2 (or classical incontinentia pigmentosa) is localized to the Xq28 region. It is due to a mutation in the IKK-gamma gene, also called NEMO (16). While mostly a disorder of females, cases have been described in males with Klinefelter’s syndrome (XXY) and somatic mosaicism with a postzygotic NEMO mutation (17).

The disorder has four stages, beginning with a phase of erythema and bullae in infancy, progressing to linear, verrucous lesions which subside, leaving widely disseminated areas of irregular, spattered, or whorled pigmentation develop. In the fourth stage, seen in adult females, subtle, faint, hypochromic, or atrophic lesions in a linear pattern are most apparent on the lower extremities.

Histopathology

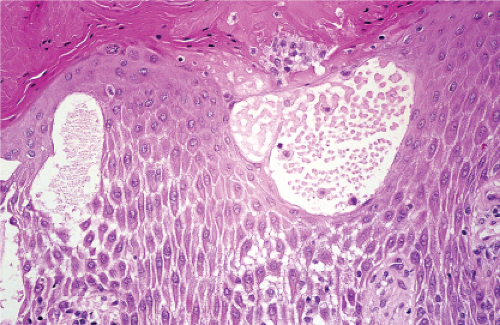

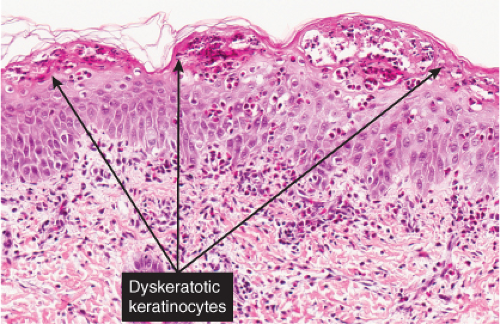

The vesicles seen during the first stage arise within the epidermis and are associated with eosinophilic spongiosis, often with single dyskeratotic cells and whorls of squamous cells with central keratinization. Like the epidermis, the dermis shows an infiltrate containing many eosinophils and some mononuclear cells. The combination of eosinophilic spongiosis, spongiotic vesiculation, and dyskeratotic keratinocytes is virtually pathognomonic of incontinentia pigmenti, being seen also only

in Grover’s disease which is easily distinguishable on other grounds (15). In the second stage, there are acanthosis, irregular papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis with intraepidermal keratinization, consisting of whorls of keratinocytes and of scattered dyskeratotic cells. The basal cells are vacuolated, and there is a decrease in their melanin content. The dermis shows a mild, chronic inflammatory infiltrate intermingled with melanophages. The areas of pigmentation seen in the third stage show extensive deposits of melanin within melanophages located in the upper dermis. In the hypopigmented/atrophic stage, there is epidermal atrophy, decreased melanin in the epidermal basal layer, apoptotic bodies, and absence of the pilosebaceous units and eccrine glands.

in Grover’s disease which is easily distinguishable on other grounds (15). In the second stage, there are acanthosis, irregular papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis with intraepidermal keratinization, consisting of whorls of keratinocytes and of scattered dyskeratotic cells. The basal cells are vacuolated, and there is a decrease in their melanin content. The dermis shows a mild, chronic inflammatory infiltrate intermingled with melanophages. The areas of pigmentation seen in the third stage show extensive deposits of melanin within melanophages located in the upper dermis. In the hypopigmented/atrophic stage, there is epidermal atrophy, decreased melanin in the epidermal basal layer, apoptotic bodies, and absence of the pilosebaceous units and eccrine glands.

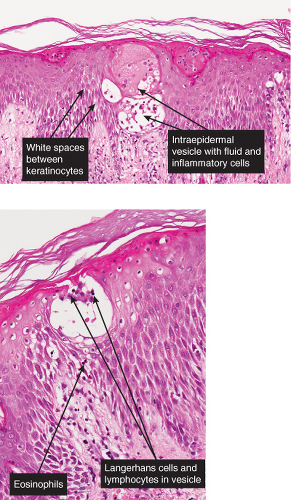

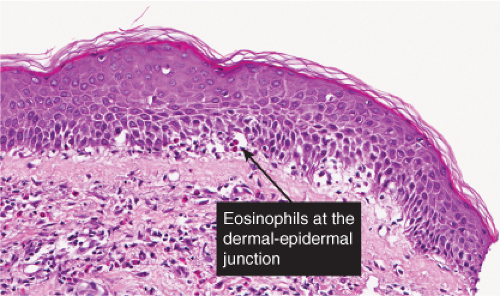

Figs. IVB2a.f,g. Incontinentia pigmenti, low and medium power. A vesicular stage lesion. Many eosinophils are seen in the dermis and in the focally acanthotic and spongiotic epidermis. |

Fig. IVB2a.h. Incontinentia pigmenti, high power. Eosinophilic spongiosis and early acanthosis, with numerous dyskeratotic keratinocytes located superficially in this example. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

spongiotic (eczematous) dermatitis

atopic dermatitis

allergic contact dermatitis

photoallergic drug eruption

Bullous pemphigoid, urticarial phase

incontinentia pigmenti, vesicular stage

IVB3 Intraspinous Spongiosis, Neutrophils Predominant

Neutrophils are seen in the epidermis, stratum corneum, and in the dermis. Aggregations of neutrophils in the superficial spinous layer constitute the spongiform pustules of Kogoj characteristic of psoriasis. Neutrophilic spongiosis has been less well characterized than eosinophilic spongiosis. It may be seen in a variety of conditions including psoriasis, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, intraepidermal blistering diseases including dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA bullous disease, and bullous lupus erythematosus (LE) which are all subepidermal immunobullous disorders in which neutrophils predominate in the inflammatory infiltrate, and in infections and infestations such as dermatophytosis, scabies, impetigo, and viral vesicular disorders (15).

Dermatophytosis

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

pustular psoriasis

Reiter’s syndrome

IgA pemphigus

subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon–Wilkinson)

Clin. Fig. IVB3. Dermatophytosis. A large erythematous patch showing central clearing and a polycyclic scaling border, which is quite narrow and threadlike.

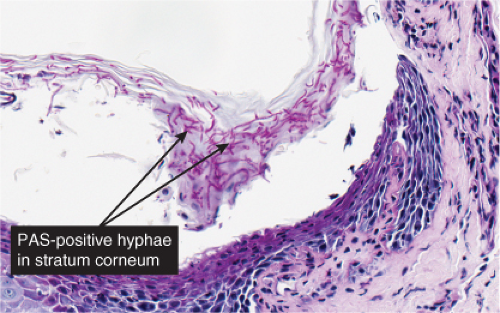

Fig. IVB3.a. Dermatophytosis, low power. There is a dense infiltrate in the dermis extending into the epidermis.

Fig. IVB3.c. Dermatophytosis, high power. PAS stain reveals hyphae within the stratum corneum. The organisms are often much less numerous than here.

exanthemic pustular drug eruptions

impetiginized dermatosis

dermatophytosis

rupial secondary syphilis

seborrheic dermatitis (see Section IIIB.1c)

epidermis adjacent to folliculitis

impetigo contagiosa

hydroa vacciniforme

mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (Kawasaki disease, pustular variant)

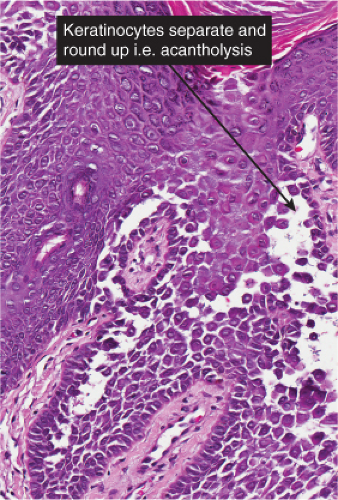

IVC Intraspinous Keratinocyte Separation, Acantholytic

There are spaces within the epidermis (vesicles, bullae). The process of separation is acantholysis. Keratinocytes within the spinous layer detach or separate from each other or from basal keratinocytes. There may be dyskeratosis, and a few eosinophils may be present in the epidermis. The infiltrate in the dermis is variable, composed of lymphocytes with or without eosinophils.

1. Intraspinous Acantholysis, Scant Inflammatory Cells

2. Intraspinous Acantholysis, Predominant Lymphocytes

2a. Intraspinous Acantholysis, Eosinophils Present

3. Intraspinous Separation, Neutrophils or Mixed Cell types

IVC1 Intraspinous Acantholysis, Scant Inflammatory Cells

The infiltrate in the dermis is scant, lymphocytic, or eosinophilic. Hailey–Hailey disease and Grover’s disease are prototypic.

Familial Benign Pemphigus (Hailey–Hailey Disease)

Clinical Summary

Familial benign pemphigus is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, with a family history obtainable in about two-thirds of the patients. It is characterized by a localized, recurrent eruption of small vesicles on an erythematous base (18). By peripheral extension, the lesions may assume a circinate configuration. The sites of predilection are the intertriginous areas, especially the axillae and the groin. Only very few instances of mucosal lesions have been reported. Mutations in ATP2Cl, encoding a calcium pump, are the cause of Hailey–Hailey Disease (19).

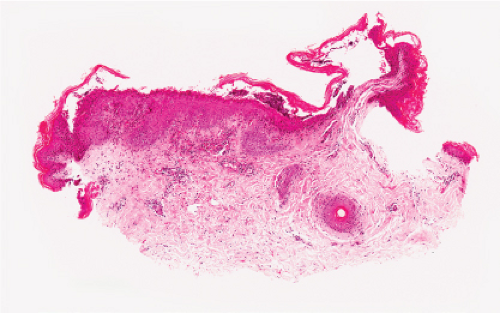

Histopathology

Although early lesions may show small suprabasal separations, so-called lacunae, in fully developed lesions, there are large separations, that is, vesicles and even bullae, in a predominantly suprabasal position. Villi, which are elongated papillae lined by a single layer of basal cells, protrude upward into the bullae, and, in some cases, narrow strands of epidermal cells proliferate

downward into the dermis. Many cells of the detached stratum malpighii show loss of their intercellular bridges, so that acantholysis affects large portions of the epidermis. Individual cells and groups of cells usually are seen in large numbers in the bulla cavity. Some acantholytic cells may exhibit premature keratinization, resembling the grains of Darier’s disease. In spite of the extensive loss of intercellular bridges, the cells of the detached epidermis in many places are only slightly separated from one another because a few intact intercellular bridges still hold them loosely together. This quite typical feature gives the detached epidermis the appearance of a dilapidated brick wall.

downward into the dermis. Many cells of the detached stratum malpighii show loss of their intercellular bridges, so that acantholysis affects large portions of the epidermis. Individual cells and groups of cells usually are seen in large numbers in the bulla cavity. Some acantholytic cells may exhibit premature keratinization, resembling the grains of Darier’s disease. In spite of the extensive loss of intercellular bridges, the cells of the detached epidermis in many places are only slightly separated from one another because a few intact intercellular bridges still hold them loosely together. This quite typical feature gives the detached epidermis the appearance of a dilapidated brick wall.

Fig. IVC1.a. Hailey–Hailey Disease, low power. The epidermis is hyperplastic and focally hyperkeratotic. There is diffuse intraepidermal separation of keratinocytes at all levels of the epidermis. |

Transient Acantholytic Dermatosis (Grover’s Disease)

Clinical Summary

Transient acantholytic dermatosis is characterized by pruritic, discrete papules, and papulovesicles on the chest, back, and thighs (20,21). In rare instances, vesicles and even bullae are seen. Most patients are middle-aged or elderly men. Although the disorder is transient in the majority of patients, lasting from 2 weeks to 3 months, it can persist for several years. Despite histologic similarity to Darier’s disease, Grover’s disease does not share an abnormality in the ATP2A2 gene (22).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree