Localized Superficial Epidermal or Melanocytic Proliferations

|

Localized superficial epithelial and melanocytic proliferations may be reactive but are often neoplastic. The epidermis (keratinocytes) may proliferate without extension into the dermis, extend into the dermis and may be squamous or basaloid. Melanocytes within the epidermis may proliferate with or without cytologic atypia (nevi, dysplastic nevi, melanoma in situ), in a proliferative epidermis (superficial spreading melanoma in situ, Spitz nevi) or an atrophic epidermis (lentigo maligna); they can also extend into the dermis as proliferative infiltrates (invasive melanoma with or without vertical growth phase). There may be an associated variably cellular often mixed inflammatory infiltrate, or inflammation may be essentially absent.

IIA Localized Irregular Thickening of the Epidermis

Localized irregular epidermal proliferations are usually neoplastic.

Localized Epidermal Proliferations

Superficial Melanocytic Proliferations

IIA1 Localized Epidermal Proliferations

The epidermis is thickened secondary to a localized proliferation of keratinocytes (acanthosis). The proliferation can be cytologically atypical, as in squamous cell carcinoma in situ, or bland, as in eccrine poroma. It may be papillary as in seborrheic keratoses and verrucae, or highly irregular as in pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma are prototypic examples. Clear cell acanthoma may also be included in this category, or may mimic an inflammatory condition.

Actinic Keratosis

Clinical Summary

Actinic keratoses (1) are usually seen as multiple lesions in sun-exposed areas of the skin in persons in or past middle life who have fair complexions. Usually, the lesions measure less than 1 cm in diameter. They are erythematous, are often covered by adherent scales, and barely palpable except in their hypertrophic form. Actinic keratoses may be regarded conceptually as local keratinocytic neoplastic proliferations characterized by architectural abnormalities and cytologic atypia, whose histopathology spans a spectrum from mild dysplasia to carcinoma in situ (2).

Histopathology

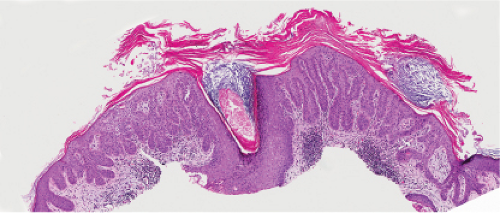

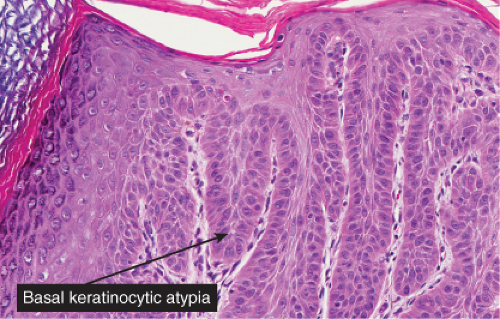

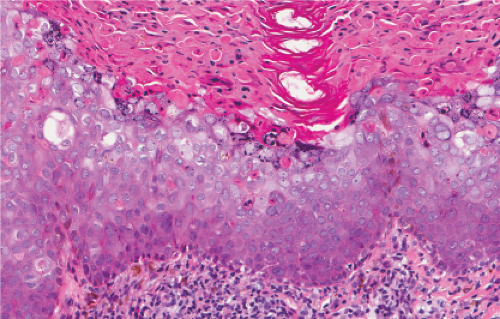

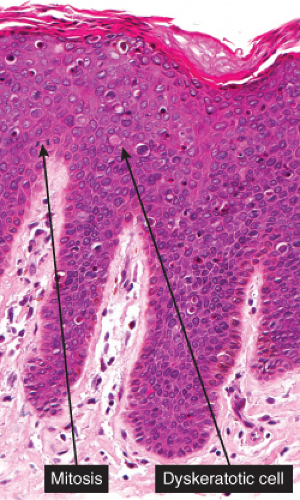

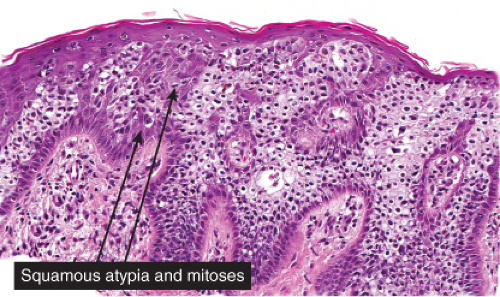

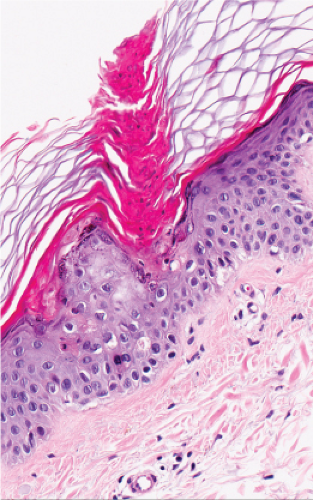

Five types of actinic keratoses can be recognized histologically: hypertrophic, atrophic, bowenoid, acantholytic, and pigmented. In the hypertrophic type, hyperkeratosis is pronounced and is intermingled with areas of parakeratosis. The epidermis is thickened in most areas and shows irregular downward proliferation that is limited to the uppermost dermis and does not represent frank invasion. Keratinocytes in the lower portion of the epidermis show a loss of polarity and thus a disorderly arrangement. Some of these cells show crowding, pleomorphism, and atypicality of their nuclei, which appear large, irregular, and hyperchromatic, and some of the cells are dyskeratotic or apoptotic, and there may be increased mitotic activity sometimes with abnormal mitoses. The degree of cytologic atypia and architectural disorder (i.e., dysplasia) can be graded as mild, moderate, or severe and has been correlated with cell cycle marker expression (3). In contrast to the epidermal keratinocytes, the cells of the hair follicles and eccrine ducts that penetrate the epidermis within actinic keratoses retain their normal appearance and keratinize normally, giving rise to the characteristic alternating columns of hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis.

Atrophic actinic keratoses lack the hypertrophic epidermal proliferation seen in the hypertrophic type; bowenoid keratoses are characterized by high grade atypia that approaches full thickness (squamous cell carcinoma in situ); acantholytic keratoses show dyshesion of lesional cells that may simulate a glandular pattern; and pigmented keratoses resemble any of the other forms but contain increased melanin pigment.

Eccrine Poroma

Clinical Summary

Eccrine poroma (4) is a fairly common solitary tumor, found most commonly on the sole or the sides of the foot, and next in frequency on the hands and fingers, but also in many other areas of the skin, such as the neck, chest, and nose. Eccrine poroma generally arises in middle-aged persons. The tumor has a rather firm consistency, is raised and often slightly pedunculated, is asymptomatic, and usually measures less than 2 cm in diameter. In eccrine poromatosis, more than 100 papules are observed on the palms and soles.

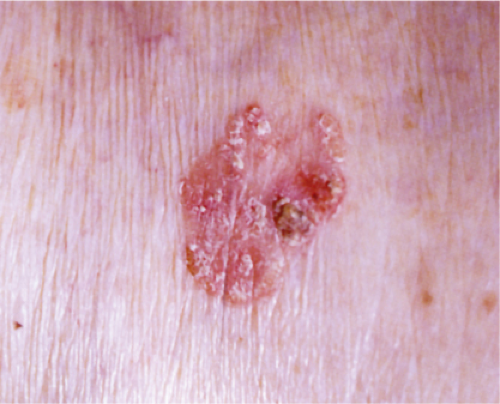

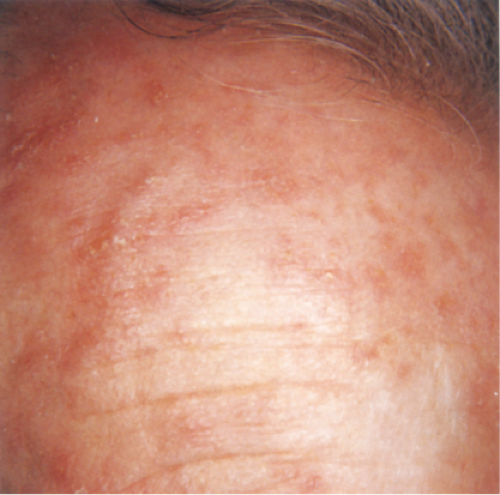

Clin. Fig. IIA1.a. Actinic keratosis. Scaly erythematous macules and papules with a “sandpaper” texture appear commonly on face and dorsal hands, areas subject to chronic sun exposure. |

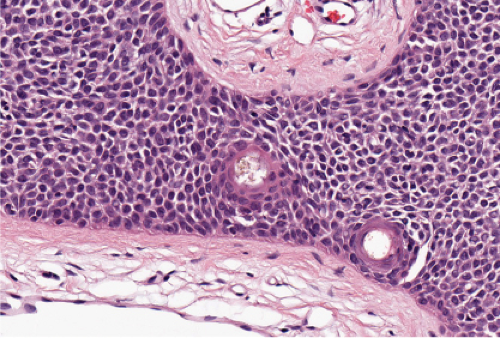

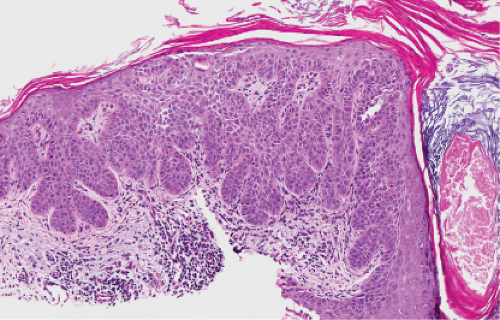

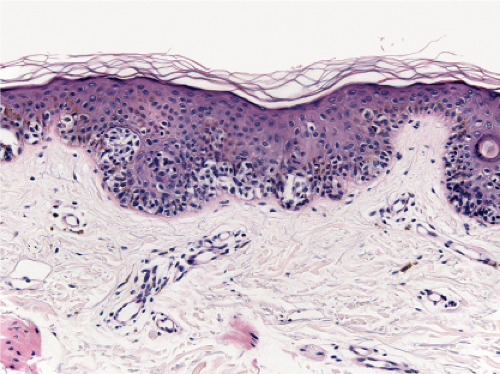

Fig. IIA1.b. Hypertrophic actinic keratosis, medium power. The normal epidermal maturation pattern is disturbed, with increased thickness of the basal layer. |

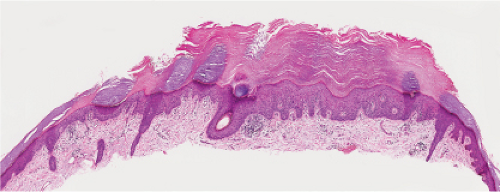

Fig. IIA1.d. Actinic keratosis, low power. This lesion demonstrates striking alternating columns of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. The epithelium is irregularly thickened. |

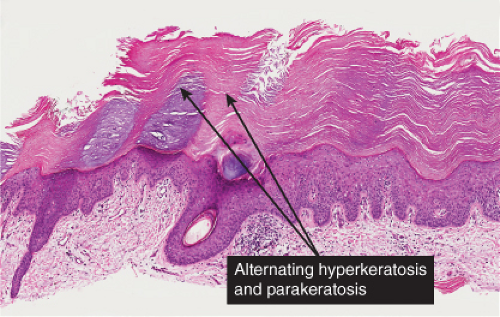

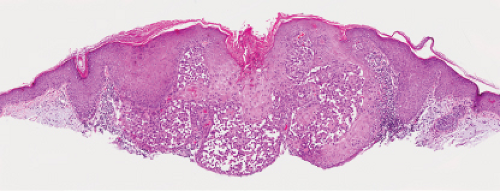

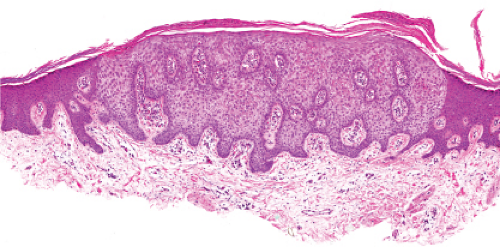

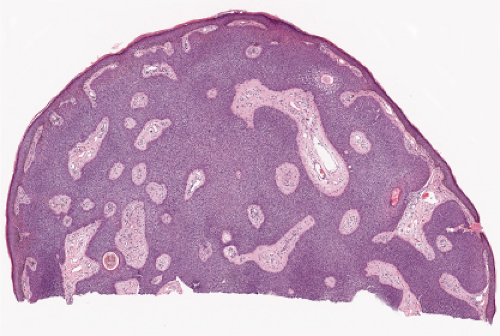

Fig. IIA1.f. Eccrine poroma, scanning magnification. There is a well-defined epidermal proliferation which is sharply circumscribed from the adjacent skin. |

Histopathology

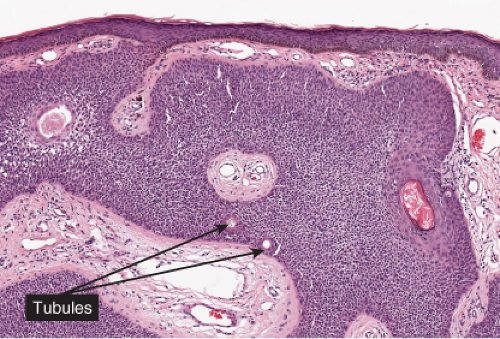

In its typical form, eccrine poroma arises within the lower portion of the epidermis, from where it extends downward into the dermis as tumor masses that often consist of broad, anastomosing bands. The tumor cells are smaller than squamous cells, have a uniform cuboidal appearance and a round, deeply basophilic nucleus, and are connected by intercellular bridges. They show no tendency to keratinize within the tumor, except on the surface. Although the border between tumor formations and the stroma is sharp, tumor cells located at the periphery show no palisading. As a characteristic feature, the tumor cells contain significant amounts of glycogen, usually in an uneven distribution. In most but not in all eccrine poromas, narrow ductal lumina and occasionally cystic spaces are found within the tumor, lined by an eosinophilic, PAS-positive, diastase-resistant cuticle similar to that lining the lumina of eccrine sweat ducts and by a single row of luminal cells.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Situ & Bowen’s Disease

Clinical Summary

Bowen’s disease usually consists of a solitary lesion manifested as a slowly enlarging erythematous patch of sharp but irregular outline, within which there are generally areas of scaling and crusting. It may occur on exposed or on unexposed skin and in pigmented or poorly pigmented skin. It may be caused on exposed skin by exposure to the sun (“Bowenoid actinic keratoses”) and on unexposed skin by the ingestion of arsenic. Some cases, especially in immunosuppressed patients and in genital and periungiual sites, may be associated with oncogenic viruses including human papilloma virus (HPV) (5), and merkel cell polyoma virus (6).

Histopathology

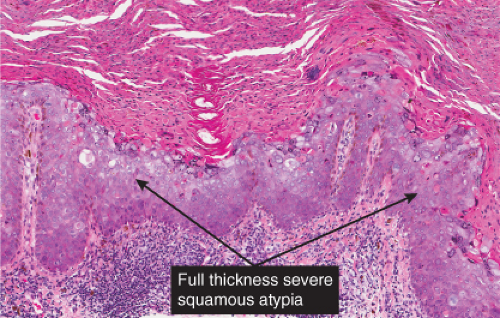

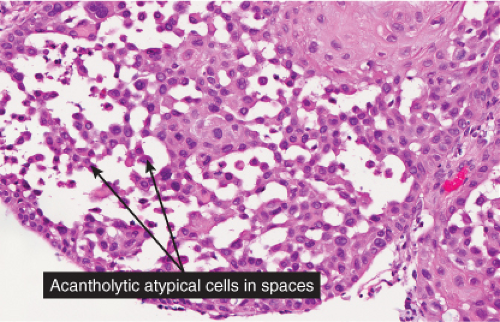

Bowen’s disease (7) is an intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma referred to also as squamous cell carcinoma in situ. When full-thickness atypia is present in an actinic keratosis, the term squamous cell carcinoma in situ may also appropriately be applied. The bowenoid type of actinic keratosis is histologically indistinguishable from Bowen’s disease. As in Bowen’s disease, there is within the epidermis considerable disorder in the arrangement of the nuclei, as well as clumping of nuclei and dyskeratosis. The epidermis is acanthotic and the cells lie in complete disorder, resulting in a “windblown” appearance. Many cells are highly atypical, with large, hyperchromatic nuclei and, frequently, multiple clustered nuclei. The horny layer usually is thickened and consists largely of parakeratotic cells with atypical, hyperchromatic nuclei. In contrast to actinic keratoses where the adnexal epithelium is hyperplastic, the infiltrate of atypical cells in Bowen’s disease frequently extends into follicular infundibula and causes replacement of the follicular epithelium by atypical cells down to the entrance of the sebaceous duct. In a small percentage of cases of Bowen’s disease, (about 3%–5%), an invasive squamous cell carcinoma develops.

Bowenoid Papulosis

Clinical Summary

As recently reviewed (8), Bowenoid papulosis presents as papules and plaques that frequently regress and relapse in vulvar and penile skin. It is best regarded as a form of squamous cell carcinoma in situ that carries a low risk of transformation to invasive carcinoma. The lesions are contagious and likely transmitted via sexual contact or vertical transmission in the peripartum period. Various high-risk HPV types, including types 16 and 18, have been linked to the disease.

Histopathology

As in Bowen’s disease, the lesions are characerised by psoriaform epidermal hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis, and focal parakeratosis. There is full-thickness epidermal dysplasia with crowding of keratinocytes and loss of architecture. The lesional cells are large, with hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei, and demonstrate loss of cellular polarity, and abnormal maturation. Mitoses, some atypical, are often seen. Partially vacuolated koilocyte-like cells are often present, and small, rounded, eosinophilic, inclusion-like bodies with a surrounding halo are sometimes present in the stratum corneum and granulosum. In comparison to Bowen’s disease, histologic changes of BP are less pronounced and more focal. There may be a lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Immunoperoxidase staining has demonstrated the presence of papillomavirus antigen in the nuclei of superficial epidermal cells.

Clin. Fig. IIA1.c. Bowenoid papulosis. A middle-aged male presented with a longstanding history of asymptomatic reddish-brown papules. |

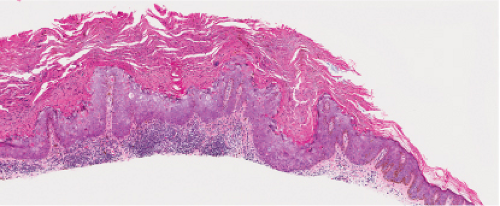

Fig. IIA1.m. Bowenoid papulosis, low power. There is mildly irregular epidermal thickening and hyperpigmentation. |

Fig. IIA1.n. Bowenoid papulosis, medium power. Focally, one can identify perinuclear vacuolization similar to what is seen in common condylomata. |

Clear Cell Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Situ

See Fig. IIA.p.

Clear Cell Acanthoma

Clinical Summary

This not uncommon tumor (9) typically occurs as a solitary lesion on the legs, as a slowly growing, sharply delineated, red nodule or plaque 1 to 2 cm in diameter, covered with a thin crust and exuding some moisture. A collarette is often seen at the periphery. The lesion appears stuck on, like a seborrheic keratosis, and is vascular, like a pyogenic granuloma.

Histopathology

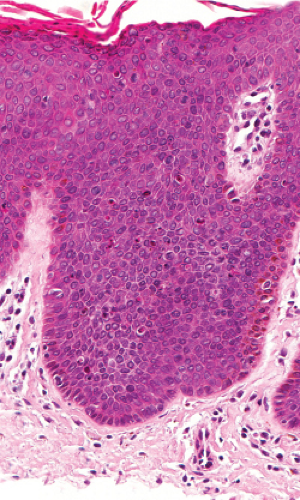

Within a sharply demarcated area of the epidermis, the epidermal cells, with the exception of those of the basal cell layer, appear strikingly clear and slightly enlarged. Their nuclei appear normal. Staining with the periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reaction reveals large amounts of glycogen within the cells. The rete ridges are elongated and

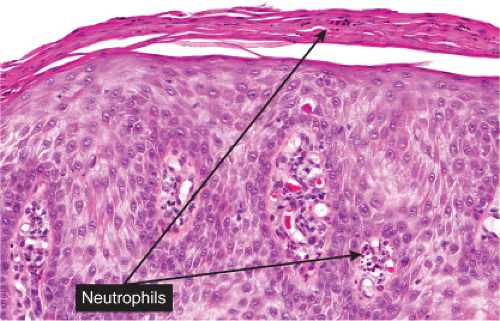

may be intertwined. The surface is parakeratotic with few or no granular cells. The acrosyringia and acrotrichia within the tumor retain their normal stainability. A conspicuous feature in most lesions is the presence throughout the epidermis of numerous neutrophils, many with fragmentation of their nuclei, often forming microabscesses in the parakeratotic horny layer. Slight spongiosis is present between the clear cells. Dilated capillaries are seen in the elongated papillae and often also in the dermis underlying the tumor. In addition, there is a mild to moderately severe lymphoid infiltrate in the dermis. Some clear cell acanthomas appear papillomatous, with the configuration of a seborrheic keratosis.

may be intertwined. The surface is parakeratotic with few or no granular cells. The acrosyringia and acrotrichia within the tumor retain their normal stainability. A conspicuous feature in most lesions is the presence throughout the epidermis of numerous neutrophils, many with fragmentation of their nuclei, often forming microabscesses in the parakeratotic horny layer. Slight spongiosis is present between the clear cells. Dilated capillaries are seen in the elongated papillae and often also in the dermis underlying the tumor. In addition, there is a mild to moderately severe lymphoid infiltrate in the dermis. Some clear cell acanthomas appear papillomatous, with the configuration of a seborrheic keratosis.

Fig. IIA1.r. Clear cell acanthoma, medium power. The lesion is composed of pale-staining, bland-appearing keratinocytes. The cells are pale because of an abundance of glycogen. |

Fig. IIA1.s. Clear cell acanthoma, high power. Upon close inspection, neutrophils can be seen throughout this lesion; they may also accumulate in the overlying stratum corneum. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

No Cytologic Atypia

seborrheic keratosis

verrucae

dermatosis papulosa nigra

stucco keratosis

large cell acanthoma

clear cell acanthoma

epidermal nevi

eccrine poroma

hidroacanthoma simplex

oral white sponge nevus

leukoedema of the oral mucosa

verrucous hyperplasia of oral mucosa (oral florid papillomatosis)

With Cytologic Atypia

actinic keratosis

arsenical keratosis

squamous cell carcinoma in situ

Bowen’s disease

erythroplasia of Queyrat

erythroplakia of the oral mucosa

Bowenoid papulosis

Pseudoepitheliomatous Hyperplasia

halogenodermas

deep fungal infections

epidermis above granular cell tumor

Spitz nevus

verrucous melanoma

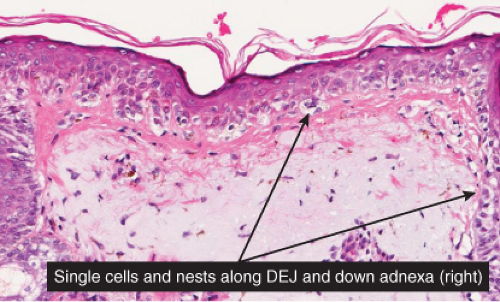

IIA2 Superficial Melanocytic Proliferations

The epidermis may be thickened (acanthosis) and is associated with a proliferation of single or nested melanocytic cells. The proliferation can be malignant as in superficial spreading melanoma or benign as in nevi. These are the prototypes.

Superficial Melanocytic Nevi and Melanomas

Clinical Summary

Melanocytic nevi (10,11) vary considerably in their clinical appearance. Five clinical types can be recognized: (1) flat lesions which are for the most part are histologically junctional nevi, and compound nevi which include (2) slightly elevated lesions often with raised centers and flat peripheries many of which are histologically dysplastic nevi, (3) dome-shaped lesions, (4) papillomatous lesions, and (5) pedunculated lesions. The first two types are usually pigmented and are superficial at the histologic level (confined to the epidermis and papillary dermis); the latter three may or may not be pigmented, and may involve the reticular dermis. Most small, flat lesions represent either a lentigo simplex or a junctional nevus; flat lesions or lesions with flat peripheries greater than 5 mm in diameter with irregular indefinite borders and pigment variegation are clinically dysplastic nevi. Dysplastic nevi are most important as simulants and markers of increased risk for melanoma. Although about one-third of melanomas may arise in a dysplastic nevus, dysplastic nevi are vastly more common than melanomas and therefore the risk of progression of any one lesion is very low (12).

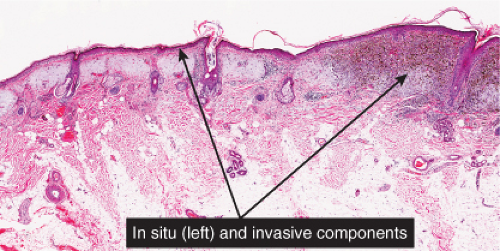

Melanomas are neoplastic proliferations of cytologically malignant melanocytes (13). Two major steps or phases of melanoma development can be distinguished. The first is the nontumorigenic or radial growth phase (RGP) which presents clinically as an irregular patch or plaque of variegated pigmentation. Histologically in this step the melanomas may be in situ or microinvasive but are non-tumorigenic (do not form a mass in the dermis) and nonmitogenic (there are no dermal mitoses). In the next step, the vertical growth phase (VGP), the lesional cells have acquired the capacity for proliferation in the dermis. A clinically evident tumor mass is usually formed (tumorigenic melanoma which may be mitogenic or nonmitogenic), often within the confines of an antecedent RGP constituting a tumor within a plaque. In occasional cases the lesion is nontumorigenic but there are dermal mitoses (mitogenic but nontumorigenic melanoma). Tumorigenic or mitogenic melanomas may have competence for metastasis, while this is extraordinarily rare in the nontumorigenic nonmitogenic RGP melanomas (14). The RGP plaque is seen histologically at the edges of the VGP tumor as a “lateral” or “horizontal” component. Three major clinicopathologic types of cutaneous radial growth phase in situ or microinvasive melanoma are recognized: the (1) superficial spreading or pagetoid, (2) lentigo maligna, and (3) acral lentiginous types. A fourth type of melanoma is defined by the lack of a discernible adjacent radial growth phase component. This is termed (4) nodular melanoma, and is discussed in Section VIB.3. Similar lesions occur in mucosal sites; when a radial growth phase is present it is commonly lentiginous.

Histopathology

Melanocytic nevi are defined and recognized by the presence of nevus cells, which, even though they are melanocytes, differ from ordinary melanocytes by being arranged at least partially in clusters or “nests,” by having a tendency toward rounded rather than dendritic cell shape, and by a propensity to retain pigment in their cytoplasm rather than to transfer it to neighboring keratinocytes. Although a histologic subdivision of nevi into junctional, compound, and intradermal nevi is generally accepted, it should be realized that these are transitional stages in the “life cycle” of nevi, which start out as junctional nevi and, after having become intradermal nevi, undergo involution, likely through a process of senescence (15). The lentigo simplex is regarded as an early or evolving form of melanocytic nevus. It has the clinical appearance of a small lenticulate or lens-shaped pigmented spot (hence the term “lentigo”), and is characterized histologically by the presence of single melanocytes arranged in contiguity about elongated rete ridges. The lack of nests at the histologic level distinguishes a lentigo from a nevus. The lentiginous pattern is seen in the common lentiginous junctional nevus, in which nevus cells in nests are present in combination with the “lentiginous pattern” just described). Dysplastic nevi also exhibit a partially lentiginous, but predominantly nested architecture. They are larger (greater than 4 to 5 mm in histologic section diameter) and there is cytologic atypia affecting randomly scattered nevus cells. Individuals with clinically and/or histologically dysplastic nevi are at increased risk of developing melanoma (16,17,18).

The lentiginous pattern of proliferation is also seen in the “lentiginous” forms of melanoma, in which in contrast to nevi the lesional cells are uniformly atypical, and

the pattern is less well organized than in nevi, often with haphazard proliferation of keratinocytes resulting in irregular thickening and thinning of the epidermis. In the most common form of melanoma, the superficial spreading type, the pattern of proliferation is termed “pagetoid” with lesional cells extending singly and in groups up into the keratinocytic epithelium, which as in lentiginous melanomas tends to be irregularly thickened and thinned. Some degree of pagetoid proliferation, often slight, is usually present in the lentiginous melanomas as well, and pagetoid proliferation may also be seen on occasion in benign nevi, especially Spitz nevi (sections IID2 and VIB3), and pigmented spindle cell nevi (see below). The lentiginous, pagetoid and nested patterns, as well as the degree of pigmentation, and the presence of actinic elastosis and also other readily recognizable histologic, clinical, and epidemiologic factors have been linked to the prevalence of mutations of BRAF and NRAS in melanomas (19); other oncogenes are in the process of categorization, and may be amenable to targeted therapy for metastatic melanoma.

the pattern is less well organized than in nevi, often with haphazard proliferation of keratinocytes resulting in irregular thickening and thinning of the epidermis. In the most common form of melanoma, the superficial spreading type, the pattern of proliferation is termed “pagetoid” with lesional cells extending singly and in groups up into the keratinocytic epithelium, which as in lentiginous melanomas tends to be irregularly thickened and thinned. Some degree of pagetoid proliferation, often slight, is usually present in the lentiginous melanomas as well, and pagetoid proliferation may also be seen on occasion in benign nevi, especially Spitz nevi (sections IID2 and VIB3), and pigmented spindle cell nevi (see below). The lentiginous, pagetoid and nested patterns, as well as the degree of pigmentation, and the presence of actinic elastosis and also other readily recognizable histologic, clinical, and epidemiologic factors have been linked to the prevalence of mutations of BRAF and NRAS in melanomas (19); other oncogenes are in the process of categorization, and may be amenable to targeted therapy for metastatic melanoma.

Junctional nevi including dysplastic nevi may exhibit an irregularly thickened epidermis but more often they tend to have regularly elongated rete ridges and are discussed in a later section (IIC.1). The pigmented spindle cell nevus of Reed is a lesion that often has a rather irregularly thickened rete pattern, and is discussed here as a prototype. In situ or microinvasive melanomas of the superficial spreading and acral lentiginous types also tend to have an irregularly thickened and thinned epidermis. The former is discussed in the section on pagetoid proliferations (IID.2), while the latter is discussed below.

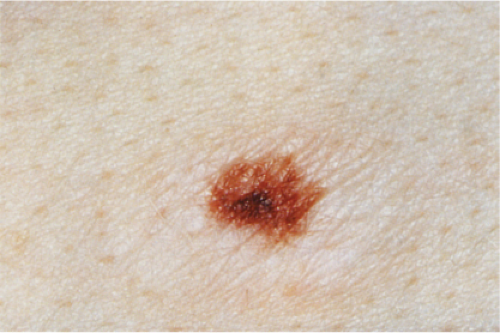

Pigmented Spindle Cell Nevus

Clinical Summary

The pigmented spindle cell nevus (60), first described by Richard Reed, may be regarded as a variant of the classical Spitz nevus. The lesions are usually 3 to 6 mm in diameter, deeply pigmented, and either flat or slightly raised dome-shaped lesions. Most patients are young adults, and the most common location is on the lower extremities. Because of the heavy pigment and the history of sudden appearance, a clinical diagnosis of melanoma is often suspected clinically. The lesions are generally stable after a relatively sudden appearance and a short-lived period of growth.

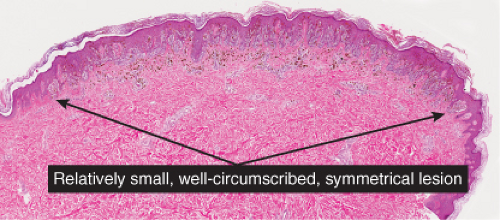

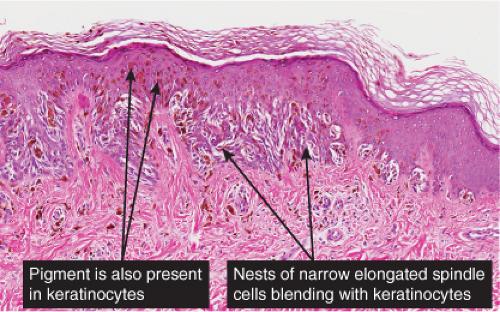

Histopathology

The lesion is characterized by its relatively small size and its symmetry, and by a proliferation of uniform, narrow, elongated, spindle-shaped, often heavily pigmented melanocytes at the dermal-epidermal junction. The epidermis tends to be irregularly thickened, and there is hyperkeratosis often with conspicuous melanin pigment in the stratum corneum. The nests of spindle cells are vertically oriented, and tend to blend with adjacent keratinocytes rather than forming clefts as in Spitz nevi. Kamino bodies may be present as in Spitz nevi. In the papillary dermis, the nevus cells lie in a compact cluster pattern, pushing the connective tissue aside. Involvement of the reticular dermis, common in Spitz nevi, is unusual in pigmented spindle cell nevi. Some lesions may show upward epidermal extension of junctional nests of melanocytes, or of single cells in a “pagetoid pattern.” In contrast to superficial spreading melanomas, pigmented spindle cell nevi are smaller, symmetrical, and show sharply demarcated lateral margins. The tumor cells appear strikingly uniform “from side to side.” If lesional cells descend into the papillary dermis, they mature along nevus lines in pigmented spindle cell nevi, in contrast to melanomas. Mitoses may be present in the epidermis in either lesion, but are uncommon in the dermis in pigmented spindle cell nevi. Abnormal mitoses are very uncommon indeed.

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma

Clinical Summary

Acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) occurs on the hairless skin of the palms and soles and in the ungual and periungual regions, the soles being the most common site (20). In groups such as Asians, Hispanics, Polynesians, and blacks, for whom the overall incidence of melanoma is low, most melanomas are of the acral type. However, the absolute incidence of acral melanoma in these groups is similar to that in Caucasians who have a much higher overall incidence of melanoma. In addition, the genetic profile differs from that of the more common superficial spreading type of melanoma, with cyclin D amplification being a common finding (21,22). Mutations of Kit are also relatively common having been described in 39% of mucosal, 36% of acral, and 28% of melanomas on chronically sun-damaged skin, but not in any (0%) melanomas on skin without chronic sun damage (23). These considerations suggest that different etiologic factors, probably not involving sunlight, are operative in acral than in other sites. Although the survival rate of patients with acral melanomas in most series is poor, this is probably a result of their typically advanced microstage and/or stage at diagnosis.

Clinically, in situ or microinvasive ALM shows uneven pigmentation with an irregular, often indefinite border. The soles of the feet are most commonly involved. If the tumor is situated in the nail matrix, the nail unit may show a longitudinal pigmented band (longitudinal melanonychia), and the pigment may extend onto the nail fold (Hutchinson’s sign). Tumorigenic vertical growth may be heralded by the onset of a nodule, with development of ulceration. However, some acral melanomas may be deeply invasive while remaining quite flat, because the thick stratum corneum acts as a barrier to exophytic growth.

Histopathology

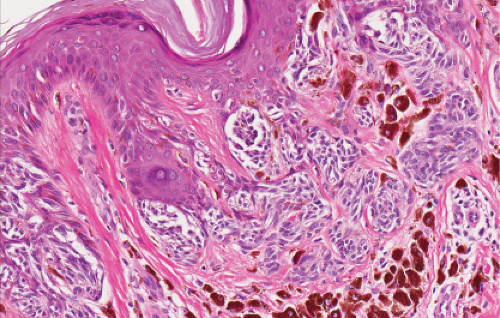

The lesions are termed “lentiginous” because majority of the lesional cells are single and

located near the dermal–epidermal junction, especially at the periphery of the lesion. Usually, however, some tumor cells can be found in the upper layers of the epidermis, especially near areas of invasion in the centers of the lesions. The histologic picture differs from that of lentigo maligna, because of irregular acanthosis, the lack of elastosis in the dermis, and the frequently dendritic character of the lesional cells. Early in situ or microinvasive lesions may show, especially at the periphery, a deceptively benign histologic picture consisting of an increase in basal melanocytes and hyperpigmentation with only focal atypia of the melanocytes. However, in the centers of the lesions, uniform, severe cytologic atypia is usually readily evident. There may be a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate that may largely obscure the dermal–epidermal junction, and in some cases this may be so dense as to simulate an inflammatory process. In most of the lesions, both spindle-shaped and rounded tumor cells are observed, and, in many cases, pigmented dendritic cells are prominent. Pigmentation is often pronounced, resulting in the presence

of melanophages in the upper dermis and of large aggregates of melanin in the broad stratum corneum. As in lentigo maligna, when tumorigenic vertical growth phase is present, it is often of the spindle cell type and not uncommonly desmoplastic and/or neurotropic. In other instances, the invasive and tumorigenic cells in the dermis may be deceptively differentiated along nevus lines.

located near the dermal–epidermal junction, especially at the periphery of the lesion. Usually, however, some tumor cells can be found in the upper layers of the epidermis, especially near areas of invasion in the centers of the lesions. The histologic picture differs from that of lentigo maligna, because of irregular acanthosis, the lack of elastosis in the dermis, and the frequently dendritic character of the lesional cells. Early in situ or microinvasive lesions may show, especially at the periphery, a deceptively benign histologic picture consisting of an increase in basal melanocytes and hyperpigmentation with only focal atypia of the melanocytes. However, in the centers of the lesions, uniform, severe cytologic atypia is usually readily evident. There may be a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate that may largely obscure the dermal–epidermal junction, and in some cases this may be so dense as to simulate an inflammatory process. In most of the lesions, both spindle-shaped and rounded tumor cells are observed, and, in many cases, pigmented dendritic cells are prominent. Pigmentation is often pronounced, resulting in the presence

of melanophages in the upper dermis and of large aggregates of melanin in the broad stratum corneum. As in lentigo maligna, when tumorigenic vertical growth phase is present, it is often of the spindle cell type and not uncommonly desmoplastic and/or neurotropic. In other instances, the invasive and tumorigenic cells in the dermis may be deceptively differentiated along nevus lines.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

junctional nevi

recurrent melanocytic nevi

pigmented spindle cell nevi

junctional and superficial compound Spitz nevi

compound or dermal nevi, papillomatous

junctional or superficial compound dysplastic nevi

in situ or microinvasive melanoma, superficial spreading type

in situ or microinvasive melanoma, acral lentiginous type

IIB Localized Lesions with Thinning of the Epidermis

A thinned epidermis is characteristic of aged or chronically sun-damaged skin. The epidermis is thinned secondary to diminished number and to decreased size of keratinocytes.

With Melanocytic Proliferation

Without Melanocytic Proliferation

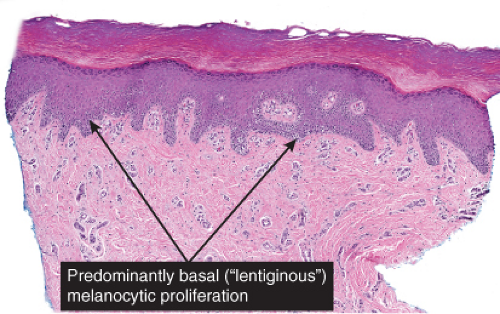

IIB1 with Melanocytic Proliferation

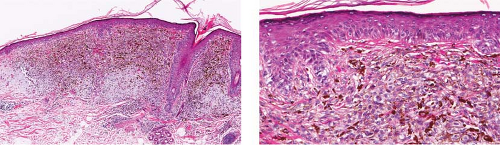

The epidermis is thinned (atrophic) and there is proliferation of single or small groups of atypical melanocytes, resulting in the localization of melanocytes in contiguity with one another, in the basal layer of the epidermis. Lentigo maligna is a prototypic example.

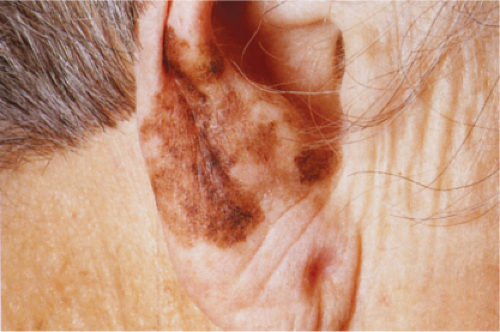

Clin. Fig. IIB1.a. Lentigo maligna melanoma. An elderly woman had a many-year history of an enlarging macule on the ear, with varying shades of brown and irregular borders. |

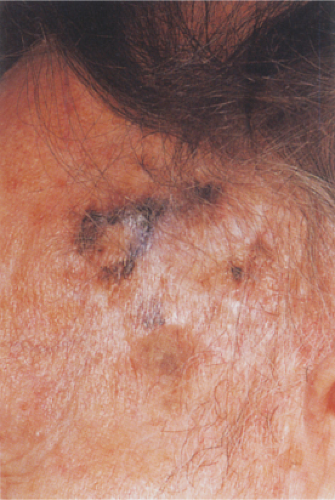

Clin. Fig. IIB1.b. Lentigo maligna melanoma. A longstanding enlarging lesion on the temple region shows variegated colors, large size, a papular component and irregular borders. |

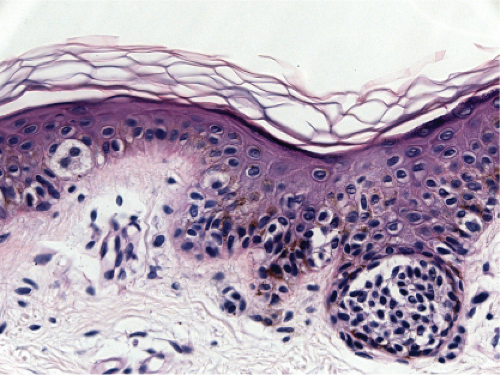

Fig. IIB1.c. Lentigo maligna, high power. Higher magnification reveals enlarged, hyperchromatic, and irregular nuclei of the majority of the lesional melanocytic cells (“uniform cytologic atypia”). |

Fig. IIB1.d,e. Lentigo maligna, medium power. There is a tumorigenic component comprising uniformly atypical cells, quite heavily pigmented in this instance. |

Lentigo Maligna Melanoma, in Situ or Microinvasive

Clinical Summary

Lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM) (24) accounts for about 10% of all melanomas and typically occurs on the chronically exposed cutaneous surfaces of the elderly, most commonly on the face. The genetic mechanisms of development of these lesions appear to be different from those operating in the more common superficial spreading melanomas, often involving NRAS rather than BRAF (33). The lesion evolves slowly over many years, starting as an unevenly pigmented macule that gradually extends peripherally and may attain a diameter of several centimeters. It has an irregular border and, as long as it remains in situ or microinvasive, is not indurated. The color is variegated ranging from light brown to brown, with dark brown, black or gray-white flecks. Fine reticulated lines are usually also present and are helpful in distinguishing the lesions from actinic lentigines.

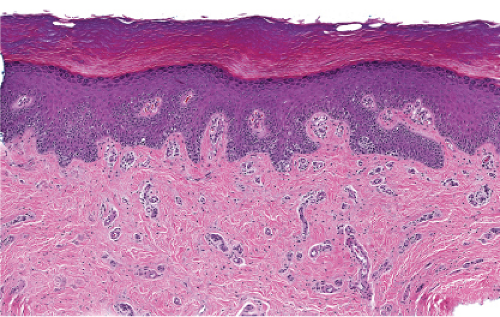

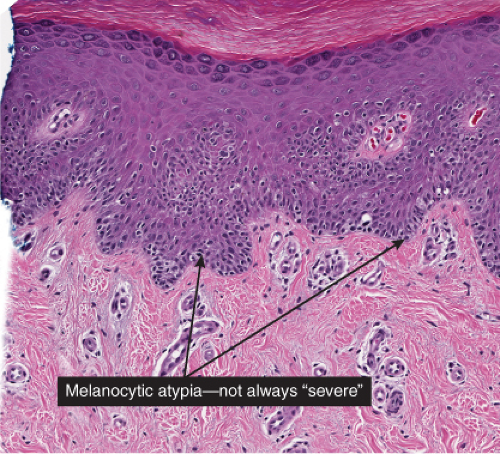

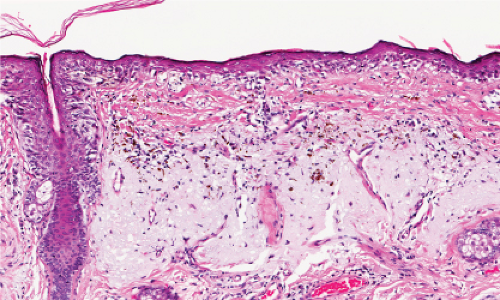

Histopathology

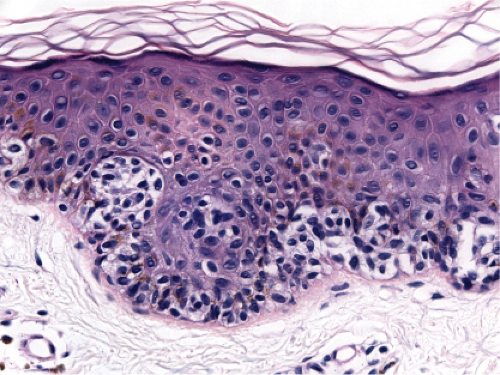

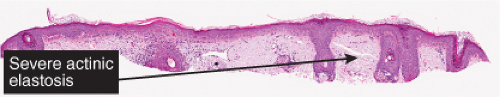

Although the earliest stages may be subtle, fully evolved lentigo maligna is characterized by contiguous proliferation of lesional melanocytes, occurring in an atrophic, flattened epidermis. This epidermal architectural pattern is in contrast to SSM, where it is irregularly thickened and thinned, or to actinic lentigines and dysplastic nevi, where there is elongation of the rete. Some lesions, termed “nevoid lentigo maligna,” may overlap histologically with dysplastic nevi and are discussed in section IIC. Cytologically, the lesional cells in classic LMM tend to be nevoid to epithelioid and sometimes elongated and spindle-shaped. Their nuclei are atypical, being slightly to moderately, or sometimes more severely enlarged, hyperchromatic, and pleomorphic. This atypia is “uniform” (i.e., present in a majority of the lesional cells), in contrast to dysplastic nevi. Frequently, atypical melanocytes extend along the basal cell layer of hair follicles, often for a considerable distance and frequently extending to the

base of a shave biopsy specimen. There is usually some upward pagetoid extension of atypical melanocytes. Although single cells predominate, some nesting of melanocytes in the basal layer may be observed. The atypical melanocytes within the nests usually retain their spindle shape, and they often “hang down” like raindrops from the interface. The upper dermis, which almost always shows severe elastotic solar degeneration, contains numerous melanophages and a rather pronounced, often bandlike, inflammatory infiltrate. Microinvasion may be demonstrable in these areas of dermal inflammation.

base of a shave biopsy specimen. There is usually some upward pagetoid extension of atypical melanocytes. Although single cells predominate, some nesting of melanocytes in the basal layer may be observed. The atypical melanocytes within the nests usually retain their spindle shape, and they often “hang down” like raindrops from the interface. The upper dermis, which almost always shows severe elastotic solar degeneration, contains numerous melanophages and a rather pronounced, often bandlike, inflammatory infiltrate. Microinvasion may be demonstrable in these areas of dermal inflammation.

The differential diagnosis of LMM includes lentiginous junctional nevi and dysplastic nevi, and actinic lentigines. All of these lesions are characterized by lentiginous elongation of rete ridges (section IIC), in contrast to the solar atrophy that characterizes the epidermis in the classic pattern of LMM. Junctional nevi exhibit little or no cytologic atypia, and dysplastic exhibit mild to moderate atypia, in contrast to the uniform moderate to severe atypia that characterizes most examples of LMM. Some examples of lesions thought to be in the general category of LMM have preserved rete ridges. These have been termed “nevoid lentigo maligna” or “lentiginous melanoma” and are discussed in Section IIC.

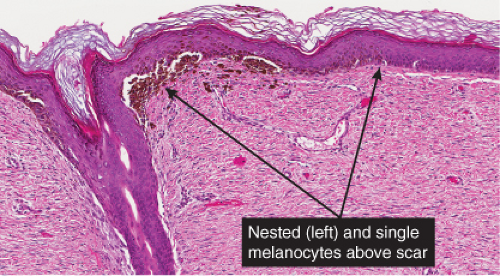

Recurrent (“Persistent”) Nevus, Lentiginous Patterns

Clinical Summary

First described by Kornen and Ackerman as “pseudomelanoma,” this relatively common

phenomenon often follows shave biopsy of a nevus (25). Clinically recurrent hyperpigmentation on biopsy may show histologic changes suggestive of melanoma. Recurrence may follow incomplete removal of a nevus, particularly by a shave biopsy or electrodessication, or the nevus may apparently have been completely excised. The pigmentation in recurrent nevi is confined to the region of the scar, and typically presents within a few weeks of the surgical procedure. After this rapid appearance, the pigment is stable. In contrast, recurrent melanoma does not respect the border of the scar, and extends over time into the adjacent skin. Paradoxically, recurrent melanoma occurs more slowly, over months or years, but progresses inexorably.

phenomenon often follows shave biopsy of a nevus (25). Clinically recurrent hyperpigmentation on biopsy may show histologic changes suggestive of melanoma. Recurrence may follow incomplete removal of a nevus, particularly by a shave biopsy or electrodessication, or the nevus may apparently have been completely excised. The pigmentation in recurrent nevi is confined to the region of the scar, and typically presents within a few weeks of the surgical procedure. After this rapid appearance, the pigment is stable. In contrast, recurrent melanoma does not respect the border of the scar, and extends over time into the adjacent skin. Paradoxically, recurrent melanoma occurs more slowly, over months or years, but progresses inexorably.

Clin. Fig. IIB1.c. (Former IID2.b). Recurrent melanocytic nevus. Dark brown macule with irregular borders recurred in the surgical site of a previously shave biopsied nevus in a teenaged girl. |

Histopathology

Although most recurrent nevi are not cytologically atypical, in a few instances they contain atypical melanocytes, both singly and in nests, arranged mainly along the epidermal–dermal junction, but occasionally also extending into the upper dermis and also into the epidermis in a pagetoid pattern (see IID2) (26). The junctional nests are often composed of pigmented epithelioid melanocytes forming irregular nests possibly the result of their growth within an atrophic epidermal layer that interfaces with scar tissue. Deep remnants of the nevus may be seen in the reticular dermis beneath the scar (27). A lymphocytic infiltrate with melanophages may be seen in the upper dermis. Nevus cells in the dermis tend to show evidence of maturation, and the Ki-67 proliferation rate is low (28). However, mitotic figures may occasionally be observed. Distinction from melanoma may be difficult without a pertinent history. However, the presence of fibrosis in the upper dermis and often of remnants of a melanocytic nevus beneath the zone of fibrosis, as well as the sharp lateral demarcation, usually make a correct diagnosis possible. As is true clinically, the recurrent nevus is confined to the epidermis above the scar, while recurrent melanoma may extend into the adjacent epidermis. However, persistent nevus, after a partial biopsy, may also involve skin adjacent to a scar. In this instance, ordinary criteria for the distinction between melanomas and nevi apply. In any problematical case in which the diagnosis is in doubt, the original biopsy should be obtained for review.

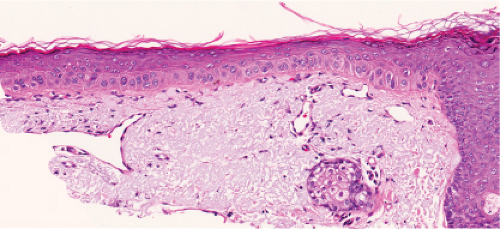

Superficial Atypical Melanocytic Proliferations of Uncertain Significance, Lentiginous Patterns

Superficial atypical melanocytic proliferations of uncertain significance (SAMPUS) is a descriptive term that may be applied to lesions that exhibit conflicting or borderline features between melanoma and its benign simulants, such as actinic lentigines with atypia, or dysplastic nevi with focal areas of confluent or continuous basal lentiginous proliferation insufficient for a more definitive diagnosis. A differential diagnosis should always be given, so that appropriate definitive therapy can be planned. Lesions that are entirely intraepidermal may be termed “Intraepidermal melanocytic proliferations of uncertain significance” (“IAMPUS”). The term “SAMPUS” is used to reflect the fact that invasion of the dermis, if not accompanied by tumorigenic and/or mitogenic proliferation in the dermis, is not associated with competence for metastasis (14). See also IID2, Page 49. The differential diagnosis for the lesion illustrated below includes a dysplastic nevus or an evolving LMM. Because of the locally recurring potential of the latter, complete

excision is indicated. Because of the risk marker significance of either diagnosis, the patient should be considered for surveillance, especially if there are other clinically atypical nevi or a family or personal history of melanoma.

excision is indicated. Because of the risk marker significance of either diagnosis, the patient should be considered for surveillance, especially if there are other clinically atypical nevi or a family or personal history of melanoma.

Fig. IIB1.h. SAMPUS, lentiginous pattern. There is a lentiginous and nested melanocytic proliferation in sun-damaged skin. The rete ridge patterns are incompletely effaced and focally exaggerated. |

Fig. IIB1.i. SAMPUS, lentiginous pattern. There are increased single cells near the dermal–epidermal junction, with some cells rising above it. |

Fig. IIB1.j. SAMPUS, lentiginous pattern. Nested and single cells are present; however, the basal proliferation is not continuous. |

Fig. IIB1.k. SAMPUS, lentiginous pattern. In another area, there is a suggestion of continuous and focal pagetoid proliferation. Cytologic atypia is moderate, but relatively uniform. |

Fig. IIB2.a. Atrophic actinic keratosis, low power. There is hyperkeratosis with patchy parakeratosis. The underlying epidermis is thin. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

melanoma in situ (lentigo maligna type)

actinic lentigo (atrophic lesions)

recurrent nevus

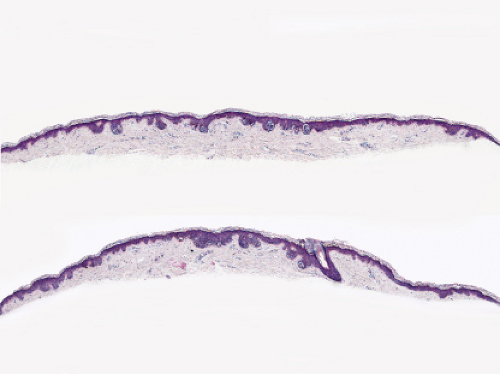

IIB2 Without Melanocytic Proliferation

The epidermis is thinned without proliferation of keratinocytes or melanocytes. Each melanocyte is separated from the next by several keratinocytes. Atrophic actinic keratosis and porokeratosis (29) are prototypic examples.

Atrophic Actinic Keratosis

(See also IIA1). Atrophic actinic keratoses lack the epidermal proliferation seen in most lesions, especially in the hypertrophic type.

Porokeratosis

Clinical Summary

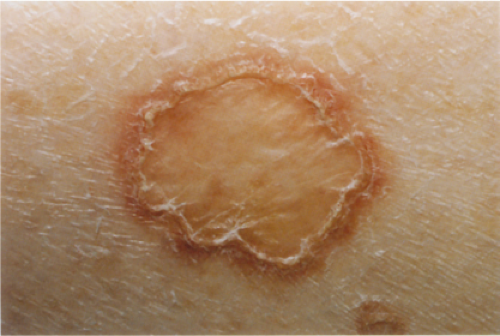

Porokeratosis (30) is characterized by a distinct peripheral keratotic ridge that corresponds histologically to the cornoid lamella. Although five different forms can be distinguished, disseminated superficial actinic

porokeratosis is by far the most common type. The lesions often are most pronounced in sun-exposed areas and may be exacerbated by exposure to the sun. They present as small patches surrounded only by a narrow, slightly raised, hyperkeratotic ridge without a distinct furrow.

porokeratosis is by far the most common type. The lesions often are most pronounced in sun-exposed areas and may be exacerbated by exposure to the sun. They present as small patches surrounded only by a narrow, slightly raised, hyperkeratotic ridge without a distinct furrow.

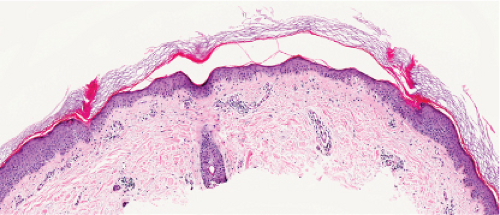

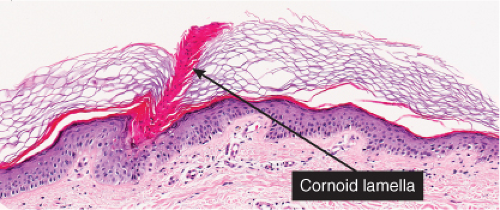

Histopathology

The peripheral, raised, hyperkeratotic ridge shows a keratin-filled invagination of the epidermis. In the prototypic plaque type of porokeratosis, the invagination extends deeply downward at an angle, the apex of which points away from the central portion of the lesion.

In the center of this keratin-filled invagination rises a parakeratotic column, the so-called cornoid lamella, representing the most characteristic feature of porokeratosis of Mibelli. In the epidermis beneath the parakeratotic column, the keratinocytes are irregularly arranged, and some cells possess an eosinophilic cytoplasm as a result of premature keratinization. Usually no granular layer is found at the site at which the parakeratotic column arises, but elsewhere the keratin-filled invagination of the epidermis has a well-developed granular layer. The histologic changes in disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis are similar but less pronounced, the central invagination being rather shallow.

In the center of this keratin-filled invagination rises a parakeratotic column, the so-called cornoid lamella, representing the most characteristic feature of porokeratosis of Mibelli. In the epidermis beneath the parakeratotic column, the keratinocytes are irregularly arranged, and some cells possess an eosinophilic cytoplasm as a result of premature keratinization. Usually no granular layer is found at the site at which the parakeratotic column arises, but elsewhere the keratin-filled invagination of the epidermis has a well-developed granular layer. The histologic changes in disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis are similar but less pronounced, the central invagination being rather shallow.

Fig. IIB.2.e. Porokeratosis, high power

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|