Disorders of the Superficial Cutaneous Reactive Unit

|

The epidermis, papillary dermis, and superficial capillary–venular plexus react together in many dermatologic conditions, and were termed the “superficial cutaneous reactive unit” by Clark. Many dermatoses are associated with infiltrates of lymphocytes with or without other cell types, around the superficial vessels. The epidermis in pathologic conditions can be thinned (atrophic), thickened (acanthotic), edematous (spongiotic) and/or infiltrated (exocytosis). The epidermis may proliferate in response to chronic irritation, infection (bacterial, yeast, deep fungal, or viral). The epidermis may proliferate in response to dermatologic conditions (psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, prurigo). The papillary dermis and superficial vascular plexus may contain a variety of inflammatory cells, can be edematous, may have increased ground substance (hyaluronic acid), and may be sclerotic or homogenized.

IIIA Superficial Perivascular Dermatitis

Many dermatoses are associated with infiltrates of lymphocytes with or without other cell types, around the vessels of the superficial capillary–venular plexus, termed by Clark the “superficial cutaneous reactive unit (SCRU)”. The vessel walls may be quite unremarkable, or there may be slight to moderate endothelial swelling. Eosinophilic change (“fibrinoid necrosis”) is not seen except in cases of true vasculitis. The term “lymphocytic vasculitis” may encompass some of the conditions mentioned here, but is of debatable validity in the absence of vessel wall damage. The epidermis is variable in its thickness, amount and type of exocytotic cell, and the integrity of the basal cell zone (liquefaction degeneration). In some of the entities listed here, the perivascular infiltrate may in some examples also involve vessels of the mid and deep vessels. These conditions are also listed in Chapter V: Pathology Substantially Involving the Reticular Dermis.

1. Mostly Lymphocytes

1a. Lymphocytes with Eosinophils

1b. With Neutrophils

1c. With Plasma Cells

1d. With Extravasated Red Cells

1e. With Prominent Melanophages

2. With Predominant Mast Cells

IIIA1 Superficial Perivascular Dermatitis, Mostly Lymphocytes

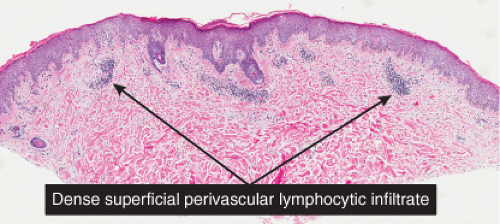

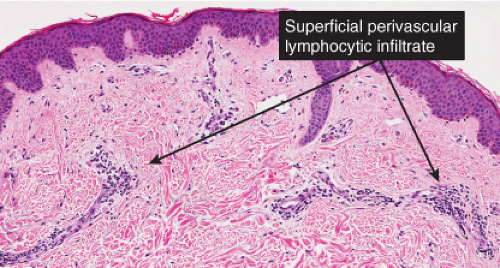

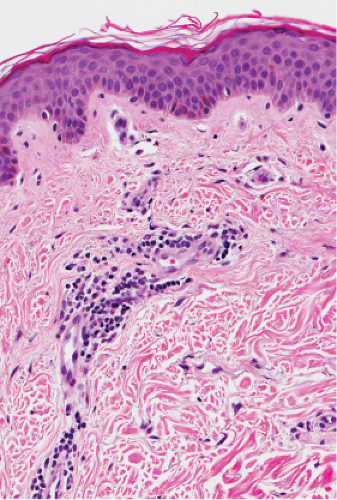

Lymphocytes are seen about the superficial vascular plexus. Other cell types are rare or absent. Viral exanthems are prototypic (1).

Viral Exanthem

Clinical Summary

At least five groups of viruses are well known to affect the skin or the adjoining mucous surfaces: (1) the herpesvirus group, including herpes simplex types 1 and 2 and the varicella-zoster virus, which are DNA-containing organisms that multiply within the nucleus of the host cell; (2) the poxvirus group, including smallpox, milkers’ nodules, orf, and molluscum contagiosum, which are DNA-containing agents that multiply within the cytoplasm; (3) the papovavirus group, including the various types of verrucae, which contain DNA and replicate in the nucleus; (4) the picornavirus group, including coxsackievirus group A, causing hand-foot-and-mouth disease, which contain RNA rather than DNA in their nucleoids; and (5) retroviruses, including human immuno-deficiency virus (HIV), the cause of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Primary HIV infection may be associated with both an exanthem and an enanthem, which are histologically nondescript lymphocytic infiltrates. The array of skin lesions associated with HIV is generally a consequence of eventual immunosuppression. Seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, xerosis, and pruritic papular eruptions may be seen in the early stages. As the infection advances and the CD4/CD8 ratio decreases, oral hairy leukoplakia, chronic herpes simplex, recurrent herpes zoster, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and other opportunistic infections, are also common (2). These associations have been recently reviewed (3). There is no unique histology of HIV infection in the skin. Primary exanthems of HIV show nonspecific lymphocytoid infiltrates with mild epidermal changes, primarily spongiosis (4). Seborrheic dermatitis in patients with AIDS may show nonspecific changes, including spotty keratinocytic necrosis, leukoexocytosis, and plasma cells in a superficial perivascular infiltrate (5). A “papular eruption” may exhibit nonspecific perivascular eosinophils with mild folliculitis, although epithelioid cell granulomas have also been reported (6). An “interface dermatitis” shows, as the name implies, vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer, scattered necrotic keratinocytes, and a superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. The vacuolar alteration and number of necrotic keratinocytes tend to be more pronounced than in drug eruptions. Biopsies of AIDS-related eruptions are often nonspecific.

The prototypic viral rash is the morbilliform rash of measles. Measles virus is a single stranded RNA virus that belongs to the family Paramyxoviridae. Measles is an epidemic disease with a worldwide distribution. Measles virus is transmitted via respiratory secretions, predominantly as aerosols but also by direct contact. The symptoms usually last for 10 days and resolve without consequence. However, there is an increased risk of more severe diseases, such as severe pneumonitis or encephalitis, in immunocompromised individuals.

Histopathology

A biopsy of the rash shows non-specific perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with epidermal spongiosis and mild vesiculation with scattered degenerated keratinocytes. Biopsies from AIDS patients with measles show necrosis of clusters of keratinocytes in the upper spinous layer and granular layer of the epidermis. Unlike in erythema multiforme the necrosis occurs in the basal layer keratinocytes. Multinucleated keratinocytes may or may not be prominent in the measles biopsy. Cytoplasmic swelling of the keratinocytes in the granular layer may be present even when multinucleated cells are sparse.

Guttate Parapsoriasis

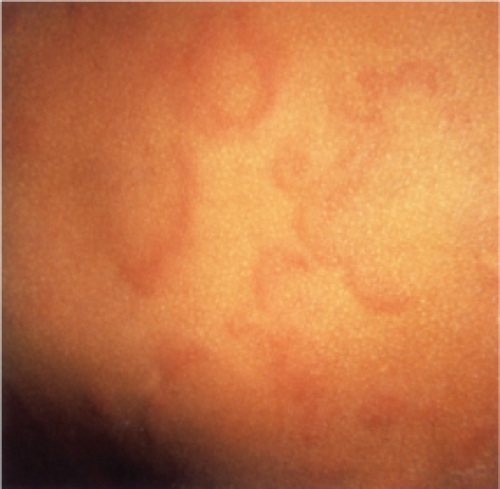

Clin. Fig. IIIA1.a. Viral exanthem. Red macules and papules that blanch are characteristic of this unique exanthem called unilateral laterothoracic viral exanthem. |

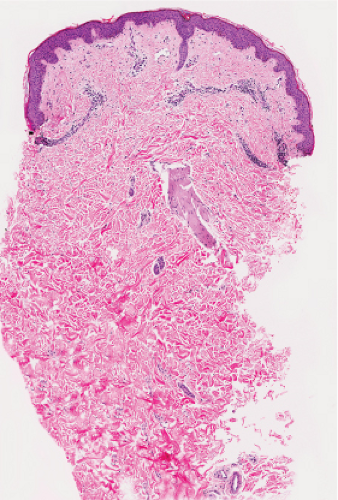

Fig. IIIA1.a. Morbilliform viral exanthem, low power. There is an inflammatory infiltrate about dermal vessels in the reticular dermis. |

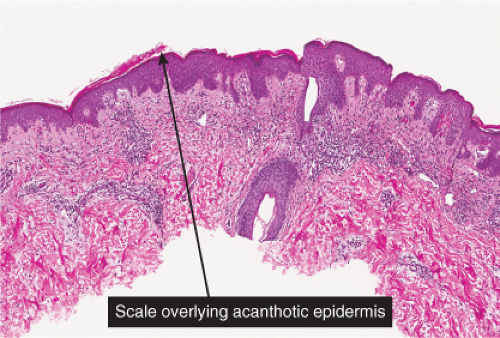

Fig. IIIA1.b. Morbilliform viral exanthem, medium power. A thin keratin scale overlies a slightly acanthotic epidermis. There is vascular ectasia in the upper reticular dermis. |

Fig. IIIA1.c. Morbilliform viral exanthem, high power. A lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate is seen about the dermal vessels. There are no eosinophils and no plasma cells. |

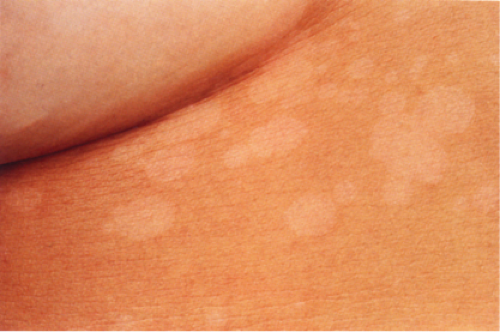

Clin. Fig. IIIA1.b. Tinea versicolor. Macular areas of hypopigmentation on the upper trunk. On gentle scraping, the surface of the discolored areas shows a fine scale. |

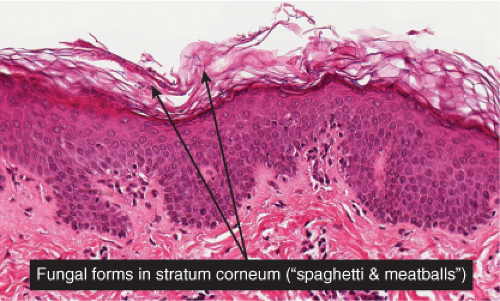

Fig. IIIA1.e. Tinea versicolor, medium power. A Grocott stain demonstrates the fungal forms in the stratum corneum. |

Clin. Fig. IIIA1.c. Former Clin. Fig. IIIA1.b. Lupus erythematosus, acute. A photosensitive female presented with edematous malar erythema’a “butterfly rash”. Lack of papules and pustules helps to distinguish lupus from rosacea. |

Clin. Fig. IIIA1.d. Former Clin. Fig. IIIA1.c. Parapsoriasis. Brown finely scaled macular fingerlike morphology with atrophy characterizes the benign digitate variant. |

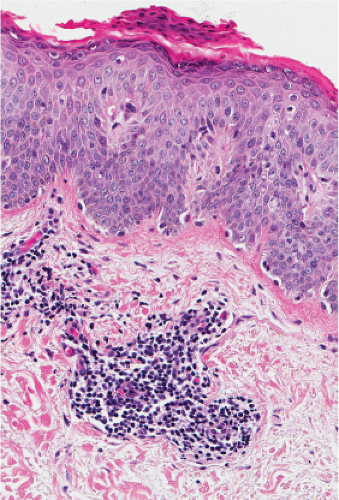

Fig. IIIA1.k. Guttate parapsoriasis, high power. There is a dense infiltrate of mononuclear cells about the dermal vessels. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

morbilliform viral exanthem

papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti–Crosti – more often spongiotic)

stasis dermatitis

pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA), early

Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate

tinea versicolor

candidiasis

superficial gyrate erythemas

lupus erythematosus, acute

mixed connective tissue disease

dermatomyositis

early herpes simplex, zoster

morbilliform drug eruption

cytomegalovirus inclusion disease

polymorphous drug eruption

progressive pigmented purpura

parapsoriasis, small plaque type (digitate dermatosis)

guttate parapsoriasis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (early lesions)

mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (Kawasaki disease)

secondary syphilis

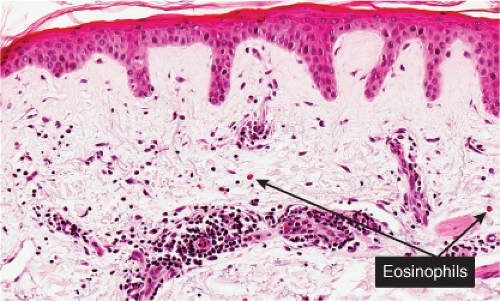

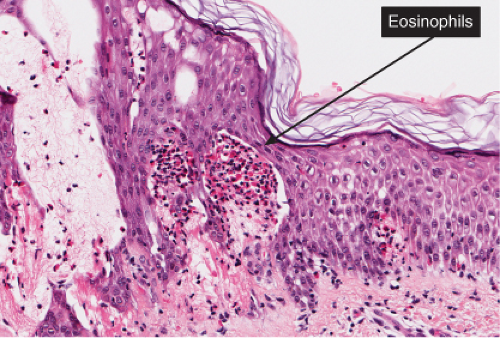

IIIA1a Superficial Perivascular Dermatitis with Eosinophils

In addition to lymphocytes, eosinophils are present in varying numbers, with both a perivascular and interstitial distribution. Morbilliform drug eruptions and urticarial reactions are prototypic (7).

Morbilliform Drug Eruption

Clinical Summary

Virtually any drug may be associated with a morbilliform eruption; the nonspecific clinical and histologic changes make definitive implication of a specific agent difficult (8,9). The most common class of medications causing morbilliform eruptions is antibacterial antibiotics. The morbilliform rash consists of fine blanching papules, which appear suddenly, are symmetric, and often are brightly erythematous in Caucasian patients.

Histopathology

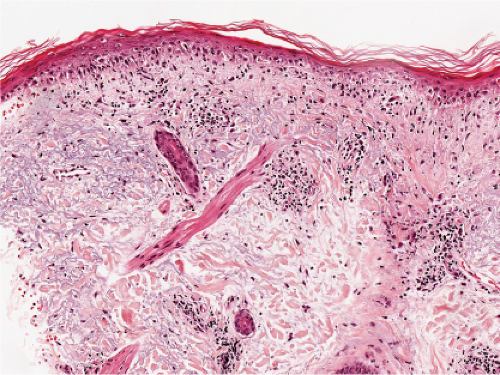

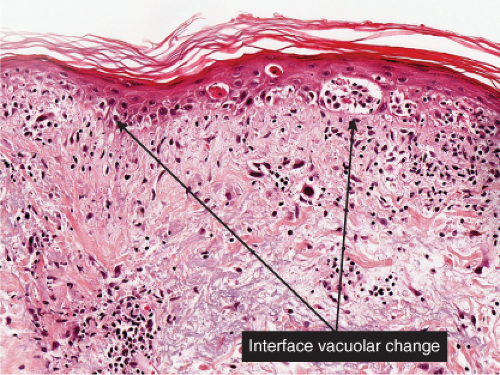

The typical morbilliform drug eruption displays a variable, often sparse, mainly perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils. Eosinophils may be absent. In a recent study, 82% of 108 cases of drug eruptions (which had been identified in a single institution by pathologic diagnosis supported by chart review) exhibited an inflammatory infiltrate confined to the superficial dermis. Eighty percent exhibited a perivascular and interstitial pattern of dermal infiltrate. The infiltrate was composed of lymphocytes and eosinophils in approximately 29% of cases, lymphocytes and neutrophils in approximately 10% of cases, and lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils in approximately 21% of cases. Therefore, eosinophils were present in only 50% of cases. Approximately half (53%) of the cases exhibited epidermal–dermal interface (e.g., vacuolar) changes (10). There is a variable degree of urticarial edema (allergic urticarial eruption, see the following text). Distinction of morbilliform drug eruption from viral exanthem in the absence of eosinophils is generally not possible. More than occasional dyskeratotic epidermal cells should prompt consideration

of erythema multiforme and related conditions, for example, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, or fixed drug eruption.

of erythema multiforme and related conditions, for example, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, or fixed drug eruption.

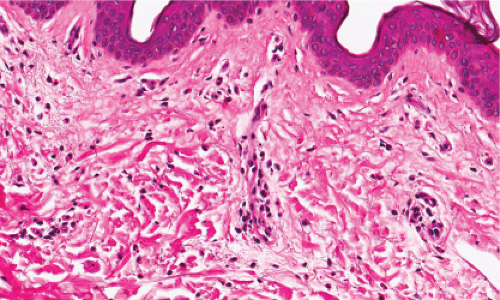

Fig. IIIA1a.b. Allergic urticarial reaction, medium power. The papillary dermis is edematous with a dense infiltrate about thick walled dermal vessels. |

Allergic Urticarial Reaction (Morbilliform Drug Eruption)

Urticaria

Clinical Summary

Urticaria is characterized by the presence of transient, recurrent wheals, which are raised, and erythematous areas of edema usually accompanied by itching. When large wheals occur, in which the edema extends to the subcutaneous tissue, the process is referred to as angioedema (11). Acute episodes of urticaria generally last only several hours. When episodes of urticaria last up to 24 hours and recur over a period of at least 6 weeks, the condition is considered chronic urticaria. Urticaria and angioedema may occur simultaneously, in which case the affliction tends to have a chronic course. In approximately 15% to 25% of patients with urticaria, an eliciting stimulus or underlying predisposing condition can be identified, including soluble antigens in foods,

drugs, insect venom, and contact allergens; physical stimuli such as pressure, vibration, solar radiation, cold temperature; occult infections and malignancies; and some hereditary syndromes. The reaction pattern of urticaria can also be seen in other conditions, notably bullous pemphigoid (7).

drugs, insect venom, and contact allergens; physical stimuli such as pressure, vibration, solar radiation, cold temperature; occult infections and malignancies; and some hereditary syndromes. The reaction pattern of urticaria can also be seen in other conditions, notably bullous pemphigoid (7).

Clin. Fig. IIIA1a.b. Urticaria. Large edematous plaques with central clearing and geographic configuration are typical of urticaria. |

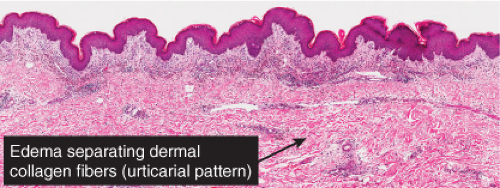

Fig. IIIA1a.d. Urticaria, low power. Sparse superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate, and separation of collagen bundles by edema fluid. |

Histopathology

In acute urticaria one observes interstitial dermal edema, dilated venules with endothelial swelling, and a paucity of inflammatory cells. In chronic urticaria interstitial dermal edema and a perivascular and interstitial mixed-cell infiltrate with variable numbers of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present. In angioedema the edema and infiltrate extend into the subcutaneous tissue. In hereditary angioedema there is subcutaneous and submucosal edema without infiltrating inflammatory cells.

Urticarial Bullous Pemphigoid

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

arthropod bite reaction

allergic urticarial reaction (drug)

bullous pemphigoid, urticarial phase

urticaria

erythema toxicum neonatorum

Well’s syndrome

mastocytosis/telangiectasia eruptiva macularis perstans

angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia

Kimura’s disease

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (early lesions)

Clin. Fig. IIIA1a.c. Bullous pemphigoid, urticarial and bullous phases. Urticarial plaques on the thigh evolved into tense bullae. |

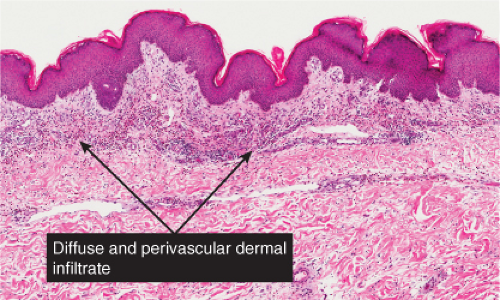

Fig. IIIA1a.g. Urticarial bullous pemphigoid, medium power. There is papillary dermal edema with a diffuse as well as perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils. |

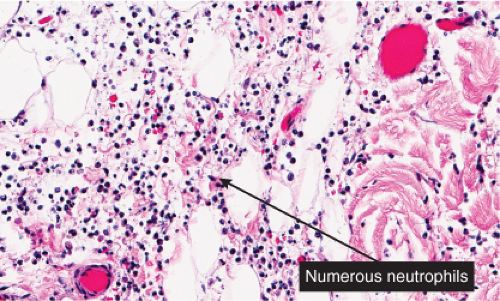

IIIA1b Superficial Perivascular Dermatitis with Neutrophils

In addition to lymphocytes, neutrophils are present in varying numbers, with both a perivascular and interstitial distribution. Cellulitis and erysipelas are prototypic (see also Section VC.2).

Erysipelas

Clinical Summary

Erysipelas is an acute superficial cellulitis of the skin caused by group A streptococci (12). It is characterized by the presence of a well-demarcated, slightly indurated, dusky red area with an advancing, palpable border. In some patients, erysipelas has a tendency

to recur periodically in the same areas. In the early antibiotic era, the incidence of erysipelas appeared to be on the decline and most cases occurred on the face. More recently, however, there appears to have been an increase in the incidence, and facial sites are now less common whereas erysipelas of the legs is predominant. Potential complications in patients with poor resistance or after inadequate therapy may include abscess formation, spreading necrosis of the soft tissue, infrequently necrotizing fasciitis, and septicemia. Erysipelas is usually produced by non-nephritogenic and non-rheumatogenic strains of streptococci.

to recur periodically in the same areas. In the early antibiotic era, the incidence of erysipelas appeared to be on the decline and most cases occurred on the face. More recently, however, there appears to have been an increase in the incidence, and facial sites are now less common whereas erysipelas of the legs is predominant. Potential complications in patients with poor resistance or after inadequate therapy may include abscess formation, spreading necrosis of the soft tissue, infrequently necrotizing fasciitis, and septicemia. Erysipelas is usually produced by non-nephritogenic and non-rheumatogenic strains of streptococci.

Histopathology

The dermis shows marked edema and dilatation of the lymphatics and capillaries. There is a diffuse infiltrate, composed chiefly of neutrophils, that extends throughout the dermis and occasionally into the subcutaneous fat. It shows a loose arrangement around dilated blood and lymph vessels. This pattern may be descriptively termed “cellulitis” and is not diagnostic of erysipelas specifically. In erysipelas, streptococci may be found in the tissue and within lymphatics, in sections stained with the Giemsa or Gram stain.

Erysipelas/Cellulitis

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

cellulitis

erysipelas

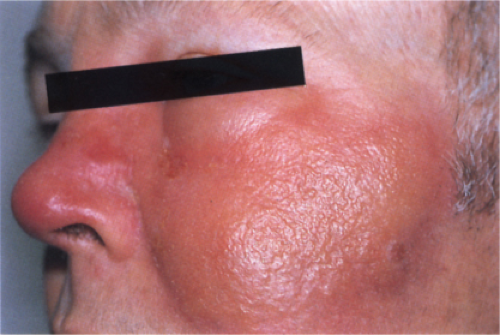

Clin. Fig. IIIA1b. Erysipelas. A 51-year-old man had fever, chills and an expanding sharply marginated erythematous edematous plaque on the cheek. |

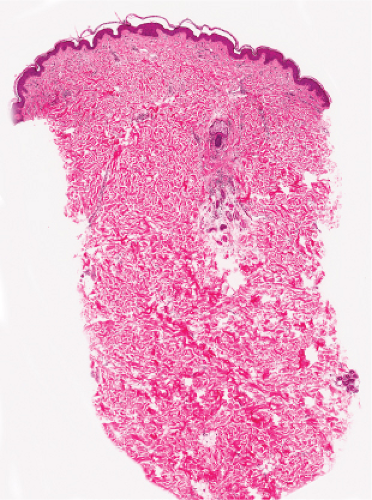

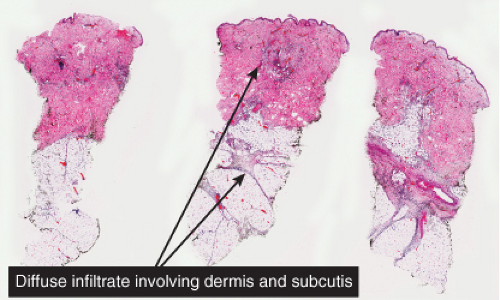

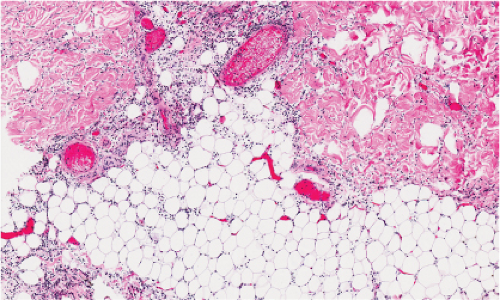

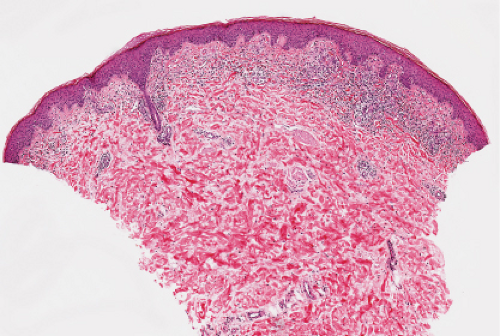

Fig. IIIA1b.a. Cellulitis, low power. The dermis shows marked edema with separation of collagen bundles and there is a diffuse cellular infiltrate involving the dermis and subcutis. |

Fig. IIIA1b.b. Cellulitis, medium power. There is marked dermal edema and a diffuse infiltrate of lymphocytes and neutrophils as well as fragmented neutrophils. |

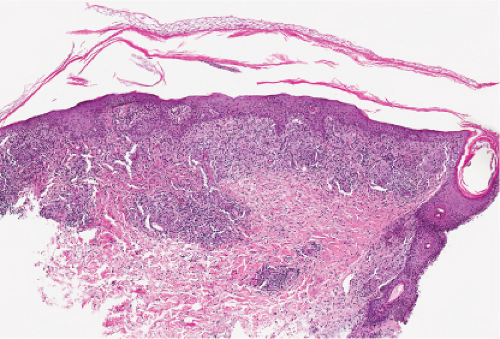

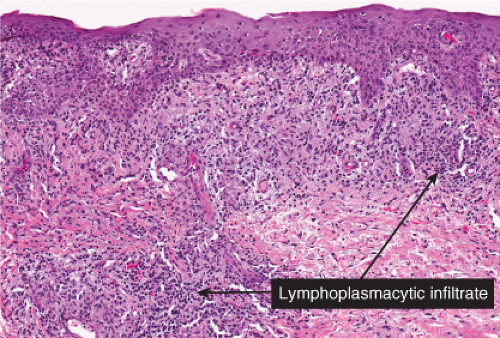

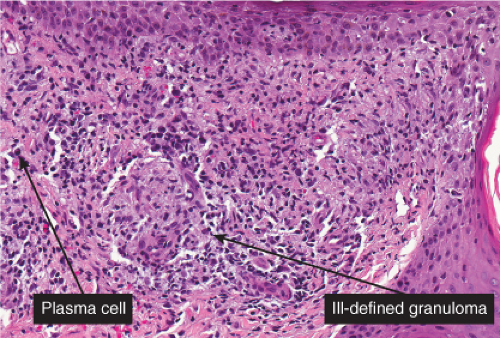

IIIA1c Superficial Perivascular Dermatitis with Plasma Cells

Plasma cells are seen about the dermal vessels as well as in the interstitium. They are most often admixed with lymphocytes. Secondary syphilis is the prototype.

Secondary Syphilis

Clinical Summary

Secondary syphilis (13), (14) is typically characterized by a generalized eruption, comprising brown–red macules and papules, papulosquamous lesions resembling guttate psoriasis, and, rarely, pustules.

Lesions may be follicular-based, annular, or serpiginous, particularly in recurrent attacks. Other skin signs include alopecia and condylomata lata, the latter comprising broad, raised, gray, confluent papular lesions arising in anogenital areas, pitted hyperkeratotic palmoplantar papules termed “syphilis cornee,” and, in rare severe cases, ulcerating lesions that define “lues maligna.” Some patients develop mucous patches composed of multiple shallow, painless ulcers.

Lesions may be follicular-based, annular, or serpiginous, particularly in recurrent attacks. Other skin signs include alopecia and condylomata lata, the latter comprising broad, raised, gray, confluent papular lesions arising in anogenital areas, pitted hyperkeratotic palmoplantar papules termed “syphilis cornee,” and, in rare severe cases, ulcerating lesions that define “lues maligna.” Some patients develop mucous patches composed of multiple shallow, painless ulcers.

Clin. Fig. IIIA1c.a. Secondary syphilis. Note characteristic scaly brown macules on the soles of the feet. |

Histopathology

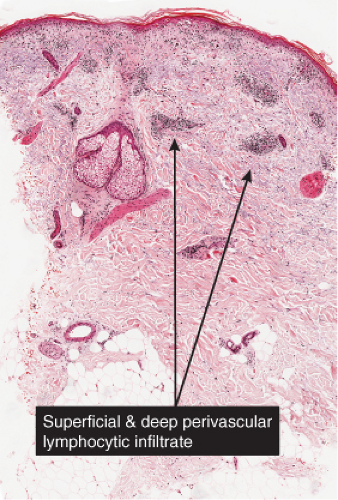

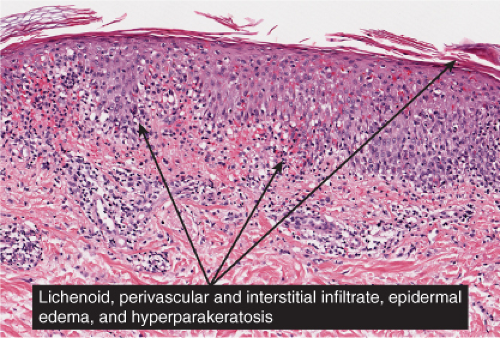

The two fundamental pathologic changes in syphilis are: (1) swelling and proliferation of endothelial cells, and (2) a predominantly perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphoid cells and often plasma cells. In late secondary and tertiary syphilis, there are also granulomatous infiltrates of epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells. Biopsies generally reveal varying degrees of lichenoid inflammation and psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with variable spongiosis and basilar vacuolar alteration. Exocytosis of lymphocytes, spongiform pustulation, and parakeratosis also may be observed, with or without intracorneal neutrophilic abscesses. Scattered necrotic keratinocytes may be observed. The dermal changes include variable papillary dermal edema and a perivascular and/or periadnexal infiltrate that usually includes plasma cells and may be lymphocyte predominant, lymphohistiocytic, histiocytic predominant, or frankly granulomatous and that is of greatest intensity in the papillary dermis and extends as loose perivascular aggregates into the reticular dermis. Vascular changes such as endothelial swelling and mural edema accompany the angiocentric infiltrates in about half of the cases. A silver stain shows the presence of spirochetes in about a third of the cases, mainly within the epidermis and less commonly around the blood vessels of the superficial plexus. Immunohistochemistry, especially when combined with specialized microscopy, results in superior detection rates (15). Lesions of condylomata lata show all of the aforementioned changes observed in macular, papular, and papulosquamous lesions, but more florid epithelial hyperplasia and intraepithelial microabscess formation are observed. Silver or IHC stains show numerous treponemes. In addition to small, sarcoidal granulomata in papular lesions of early secondary syphilis, late secondary syphilis may show extensive lymphoplasmacellular and histiocytic infiltrates resembling nodular tertiary syphilis.

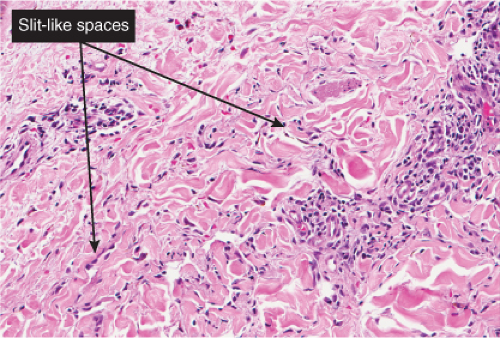

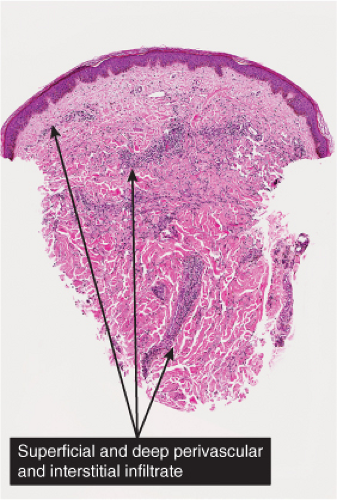

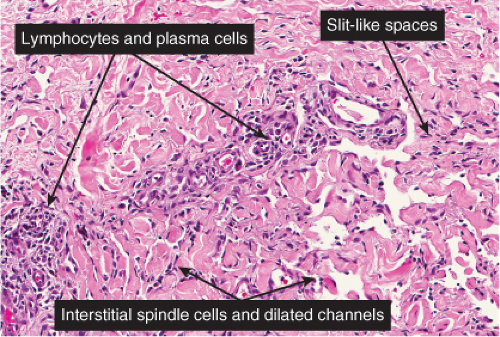

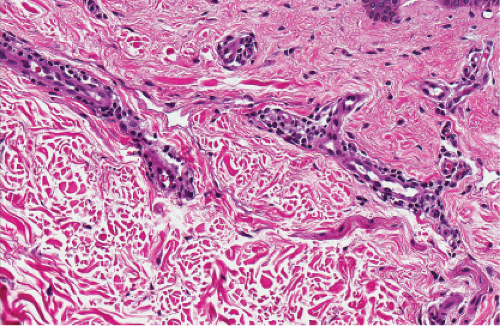

Kaposi’s Sarcoma, Patch Stage

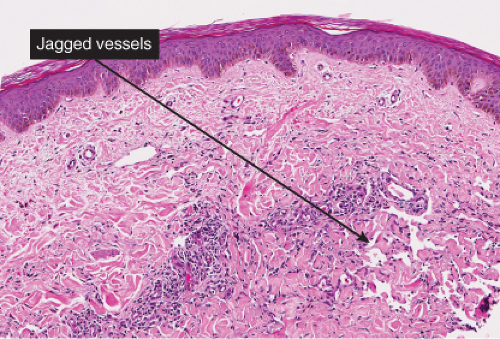

The histologic spectrum of Kaposi’s disease can be divided into stages roughly corresponding to the clinical type of lesion: early and late macules, plaques, nodules, and aggressive late lesions. In early macules there is usually a patchy, sparse, upper dermal perivascular infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Narrow cords of cells, with evidence of luminal differentiation, are insinuated between collagen bundles. Usually a few dilated irregular or angulated lymphatic-like spaces lined by delicate endothelial cells are also present. Vessels with

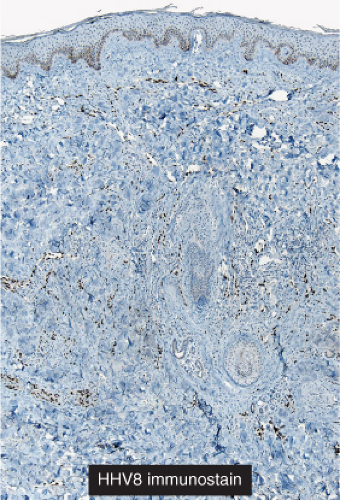

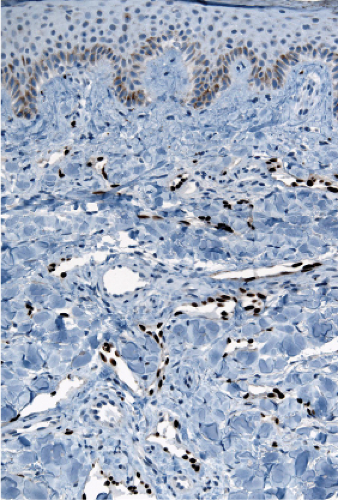

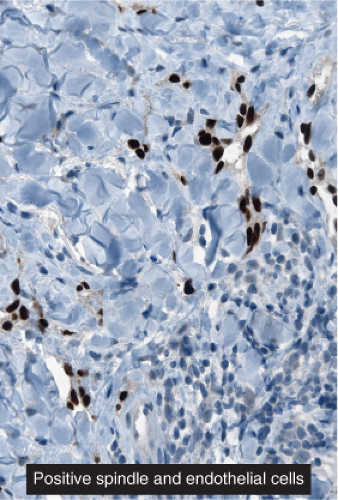

“jagged” outlines tending to separate collagen bundles are especially characteristic. Normal adnexal structures and preexisting blood vessels often protrude into newly formed blood vessels, a finding known as the “promontory sign”. In late macular lesions there is a more extensive infiltrate of vessels in the dermis, with “jagged” vessels and with cords of thicker-walled vessels similar to those in granulation tissue. At this stage, red blood cell extravasation and siderophages may be encountered. The presence of slit-like vascular spaces is a characteristic histologic finding. This condition is now known to be associated with HHV-8 infection in a susceptible host (see Section VIC5).

“jagged” outlines tending to separate collagen bundles are especially characteristic. Normal adnexal structures and preexisting blood vessels often protrude into newly formed blood vessels, a finding known as the “promontory sign”. In late macular lesions there is a more extensive infiltrate of vessels in the dermis, with “jagged” vessels and with cords of thicker-walled vessels similar to those in granulation tissue. At this stage, red blood cell extravasation and siderophages may be encountered. The presence of slit-like vascular spaces is a characteristic histologic finding. This condition is now known to be associated with HHV-8 infection in a susceptible host (see Section VIC5).

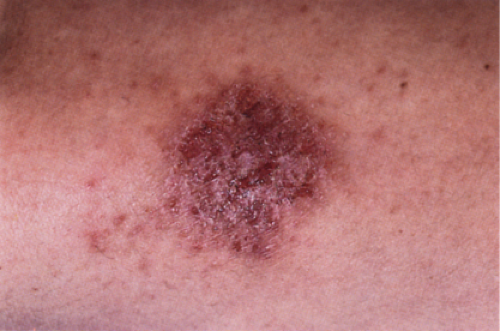

Clin. Fig. IIIA1c.b. Kaposi’s sarcoma. These purplish macules and plaques developed in an elderly Italian male. |

Fig. IIIA1c.d. Kaposi’s sarcoma, patch stage, medium power. The epidermis is effaced. In the dermis there is an impression of increased cellularity. (continues) |

Fig. IIIA1c.e. Kaposi’s sarcoma, patch stage, low power. There is a perivascular and diffuse cellular infiltrate and an increased number of thin walled blood vessels. |

Fig. IIIA1c.g. Kaposi’s sarcoma, patch stage, high power. In addition to the jagged vessels, there are spindle cells placed among dermal collagen bundles, with a tendency to form slit-like spaces. |

Fig. IIIA1c.h. Kaposi’s sarcoma, patch stage, low power. HHV8 immunostaining in a patch stage lesion shows positive intranuclear positivity in scattered cells in the reticular dermis. |

Fig. IIIA1c.i. Kaposi’s sarcoma, patch stage, low power. The HHV8 positive cells are seen to be lining vascular channels. |

Fig. IIIA1c.j. Kaposi’s sarcoma, patch stage, low power. HHV8 positive cells infiltrating among reticular dermis collagen bundles as single cells and as cells lining vascular channels. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

secondary syphilis

arthropod bite reaction

Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-specific patch stage

actinic keratoses and Bowen’s disease

Zoon’s plasma cell balanitis circumscripta

erythroplasia of Queyrat

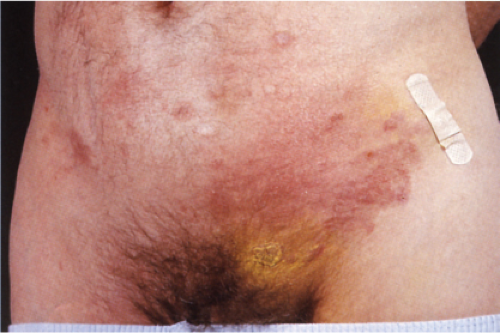

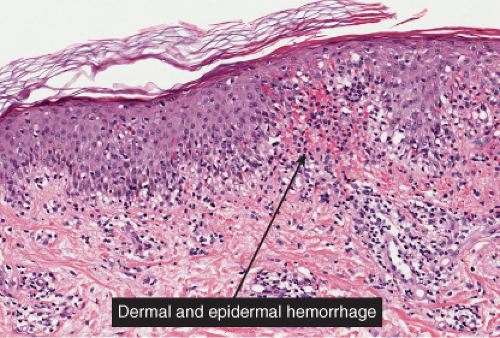

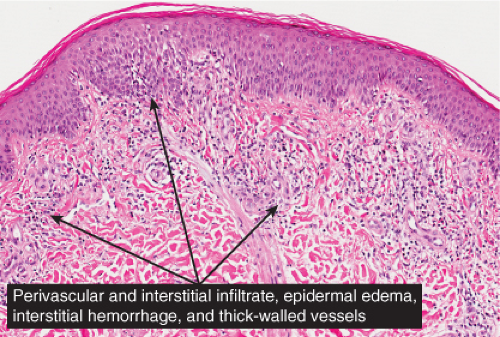

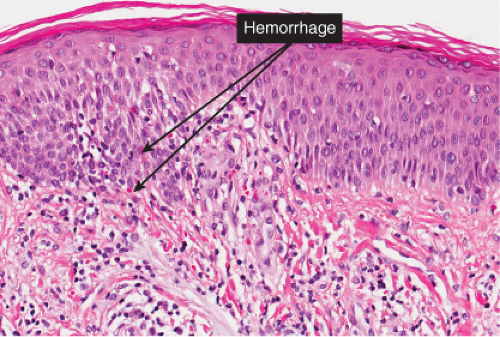

IIIA1d Superficial Perivascular Dermatitis, with Extravasated Red Cells

A perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate is associated with extravasation of lymphocytes, without fibrinoid necrosis of vessels. Pityriasis rosea (16,17) and PLEVA are prototypic.

Pityriasis Rosea

Clinical Summary

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited dermatitis lasting from 4 to 7 weeks. It frequently starts with a larger herald patch followed by a disseminated eruption. The lesions, found chiefly on the trunk, neck, and proximal extremities, consist of round to oval salmon-colored patches following the lines of cleavage and showing peripherally attached, thin, cigarette-paper–like scales. Several typical and atypical clinical variants have been described including papular, vesicular, urticarial, purpuric, and recurrent forms. The cause of pityriasis rosea is still unknown, although a viral etiology such as human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7) is suspected (18). Cell-mediated immunity may be involved in the pathogenesis due to the presence of activated helper-inducer T lymphocytes in the epidermal and dermal infiltrate in association with an increased number of Langerhans’ cells, and the expression of HLA-DR+ antigen on the surface of keratinocytes located around the area of lymphocytic exocytosis (19).

Histopathology

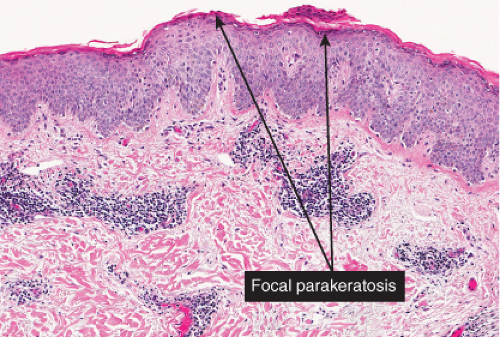

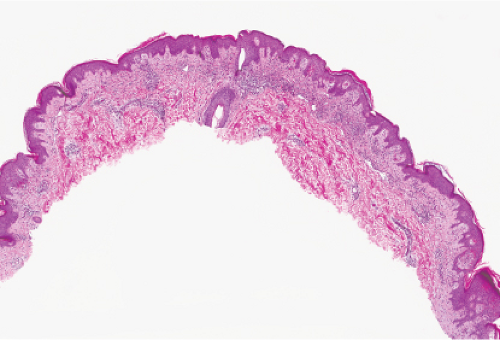

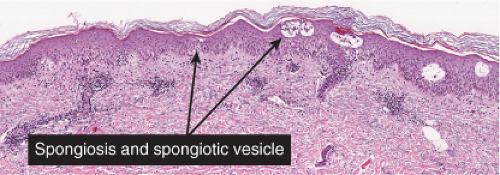

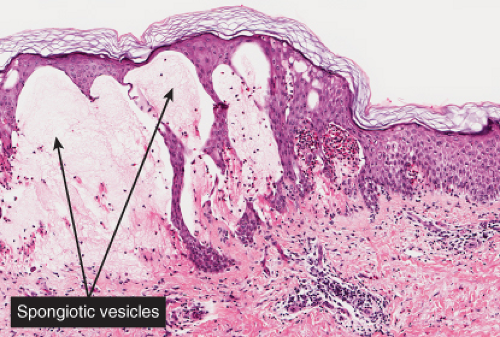

The patches of the disseminated eruption show a superficial perivascular infiltrate in the dermis that consists predominantly of lymphocytes, with occasional eosinophils and histiocytes. Lymphocytes extend into the epidermis (exocytosis), where there is

spongiosis, with intracellular edema, mild to moderate acanthosis, areas of decreased or absent granular layer, and focal parakeratosis with or without plasma cells. Intraepidermal spongiotic vesicles and a few necrotic keratinocytes are found in some cases. A common feature is the presence of extravasated erythrocytes in the papillary dermis, which sometimes extends into the overlying epidermis. Occasionally, multinucleated keratinocytes in the affected epidermis can be seen. Late lesions from the disseminated eruption are more likely to have a psoriasiform or lichen planus-like appearance and a relatively increased number of eosinophils in the inflammatory infiltrate.

spongiosis, with intracellular edema, mild to moderate acanthosis, areas of decreased or absent granular layer, and focal parakeratosis with or without plasma cells. Intraepidermal spongiotic vesicles and a few necrotic keratinocytes are found in some cases. A common feature is the presence of extravasated erythrocytes in the papillary dermis, which sometimes extends into the overlying epidermis. Occasionally, multinucleated keratinocytes in the affected epidermis can be seen. Late lesions from the disseminated eruption are more likely to have a psoriasiform or lichen planus-like appearance and a relatively increased number of eosinophils in the inflammatory infiltrate.

Clin. Fig. IIIA1d.a. Pityriasis rosea. Oval brown patches following the lines of cleavage which may show peripheral, thin scales. |

Fig. IIIA1d.b. Pityriasis rosea, medium power. The dermal papillae are widened, edematous and contain an infiltrate of lymphocytes and red blood cells. |

Pityriasis Lichenoides

Clinical Summary

Pityriasis lichenoides is an uncommon cutaneous eruption usually classified in two forms that differ in severity. The milder form, called pityriasis lichenoides chronica, is characterized by recurrent crops of brown–red papules 4 to 10 mm in size, mainly on the trunk and extremities, which are covered with a scale and generally involute within 3–6 weeks with postinflammatory pigmentary changes. The more severe form, called PLEVA or Mucha-Habermann disease, consists of a fairly extensive eruption, present mainly on the trunk and proximal extremities. It is characterized by erythematous papules that develop into papulonecrotic, occasionally hemorrhagic or vesiculopustular lesions that resolve within a few weeks, and can result in scarring (see also Section VB2). Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD) is a rare very severe variant that can be life-threatening (20).

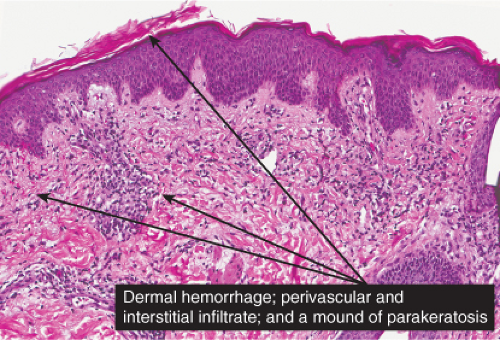

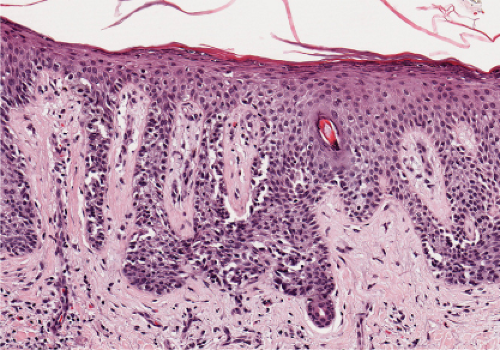

Histopathology

In pityriasis lichenoides chronica, there is a superficial perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes that extend into the epidermis, where there is vacuolar alteration of the basal layer, mild spongiosis, a few necrotic keratinocytes, and confluent parakeratosis. Melanophages and small numbers of extravasated erythrocytes are commonly seen in the papillary dermis. In PLEVA, the more severe form, the perivascular (predominantly lymphocytic) infiltrate is dense in the papillary dermis and extends into the reticular dermis in a wedge-shaped pattern. The infiltrate obscures the dermal–epidermal

junction with pronounced vacuolar alteration of the basal layer, marked exocytosis of lymphocytes and erythrocytes, and intercellular and intracellular edema leading to variable degree of epidermal necrosis. Ultimately, erosion or even ulceration may occur. The overlying cornified layer shows parakeratosis and a scaly crust with neutrophils in the more severe cases. Variable degrees of papillary dermal edema, endothelial swelling, and extravasated erythrocytes are seen in the majority of cases. Most of the cells in the inflammatory infiltrate are activated T lymphocytes. There is a predominance of CD8+ (cytotoxic-suppressor) over CD4+ (helper-inducer) T lymphocytes in the infiltrate, and there is expression of HLA-DR on the surrounding keratinocytes, suggesting a direct cytotoxic immune reaction in the pathogenesis of epidermal necrosis. Recent studies have suggested that PLEVA is a clonal T-cell disorder (21), although reports of patients with pityriasis lichenoides who have developed cutaneous lymphoma are rare. It is suggested that monoclonal expansion of T cells results most likely from a host immune response to an as yet unidentified antigen, perhaps a viral one (19).

junction with pronounced vacuolar alteration of the basal layer, marked exocytosis of lymphocytes and erythrocytes, and intercellular and intracellular edema leading to variable degree of epidermal necrosis. Ultimately, erosion or even ulceration may occur. The overlying cornified layer shows parakeratosis and a scaly crust with neutrophils in the more severe cases. Variable degrees of papillary dermal edema, endothelial swelling, and extravasated erythrocytes are seen in the majority of cases. Most of the cells in the inflammatory infiltrate are activated T lymphocytes. There is a predominance of CD8+ (cytotoxic-suppressor) over CD4+ (helper-inducer) T lymphocytes in the infiltrate, and there is expression of HLA-DR on the surrounding keratinocytes, suggesting a direct cytotoxic immune reaction in the pathogenesis of epidermal necrosis. Recent studies have suggested that PLEVA is a clonal T-cell disorder (21), although reports of patients with pityriasis lichenoides who have developed cutaneous lymphoma are rare. It is suggested that monoclonal expansion of T cells results most likely from a host immune response to an as yet unidentified antigen, perhaps a viral one (19).

Clin. Fig. IIIA1d.b. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA). Erythematous papules and papulonecrotic lesions developed suddenly on the trunk of a young man. |

Fig. IIIA1d.f. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica. A focal lesion characterized by hyperkeratosis and a lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate. |

Fig. IIIA1d.g. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica. There is hyperkeratosis without the scale-crust or frank necrosis that may be seen in lesions of PLEVA. |

Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

Clinical Summary

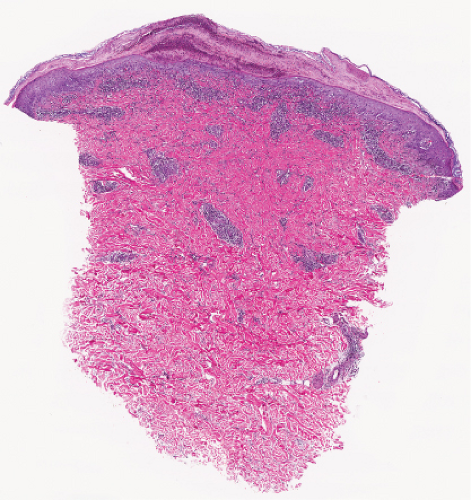

Although several variants of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD) have been described, they are all closely related and often cannot be reliably distinguished on clinical or histologic grounds (22). Clinically, the primary lesion consists of discrete puncta often limited to the lower extremities. Gradually, telangiectatic puncta appear as a result of capillary dilatation, and pigmentation as a result of hemosiderin deposits. In some cases, the findings may mimic those of stasis. Not infrequently, clinical signs of inflammation are present, such as erythema, papules, scaling, and lichenification. There are no systemic symptoms related to this disease process. The categorization of PPD as a form of cutaneous lymphoid dyscrasia has been suggested (23).

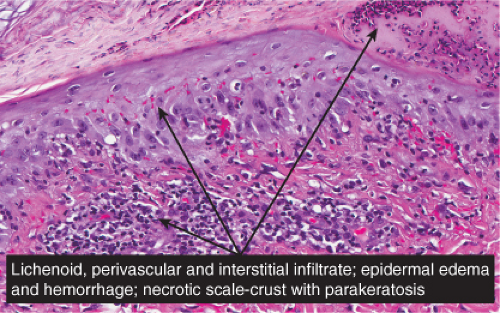

Histopathology

The basic process is a lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate limited to the papillary dermis. In some instances, the infiltrate may assume a band-like or lichenoid pattern, and may involve the reticular dermis in a perivascular distribution. Evidence of vascular damage may be present. The extent of vascular injury is usually mild and insufficient to justify the term “vasculitis”,

commonly consisting only of endothelial cell swelling and dermal hemorrhage. Extravasated red blood cells are usually found in the vicinity of the capillaries. In old lesions, the capillaries often show dilatation of their lumen and proliferation of their endothelium. Extravasated red blood cells may no longer be present, but one frequently finds hemosiderin, in varying amounts. The inflammatory infiltrate is less pronounced than in the early stage.

commonly consisting only of endothelial cell swelling and dermal hemorrhage. Extravasated red blood cells are usually found in the vicinity of the capillaries. In old lesions, the capillaries often show dilatation of their lumen and proliferation of their endothelium. Extravasated red blood cells may no longer be present, but one frequently finds hemosiderin, in varying amounts. The inflammatory infiltrate is less pronounced than in the early stage.

Clin. Fig. IIIA1d.d. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis (Gougerot Blum). 15-year-old boy developed asymptomatic nonblanching orange-brown and erythematous lichenoid papules on the lower extremities. |

Fig. IIIA1d.i. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis, low power. An ortho and parakeratotic scale are present overlying an acanthotic epidermis. There is an inflammatory infiltrate in the papillary dermis. |

Fig. IIIA1d.l. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis, low power. There is a superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. |

Fig. IIIA1d.n. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis, high power. The brown granules stain blue in an iron stain. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

pityriasis rosea

lupus erythematosus, subacute

lupus erythematosus, acute

postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

stasis dermatitis

Kaposi’s sarcoma, patch stage

PLEVA

pityriasis lichenoides chronica

pigmented purpuric dermatoses (Gougerot-Bloom)

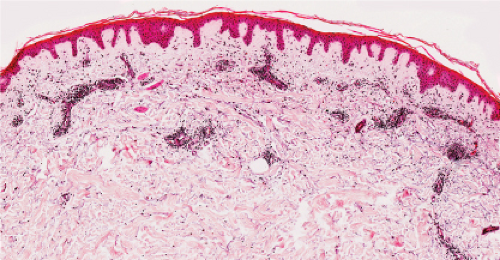

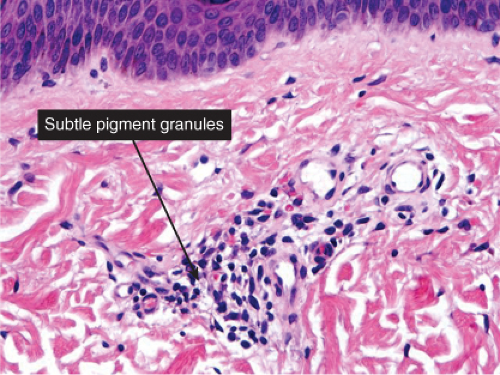

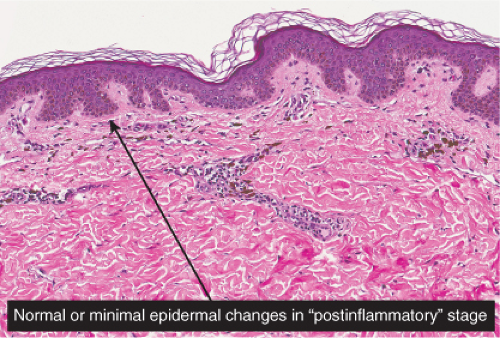

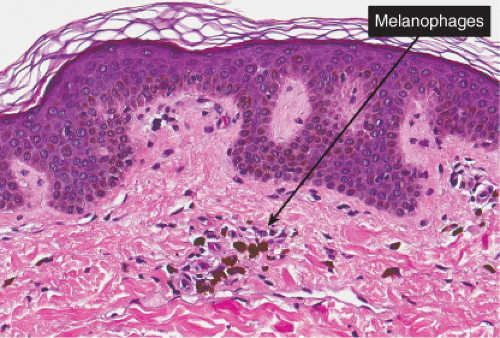

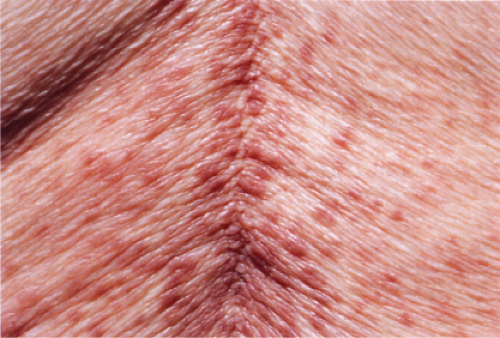

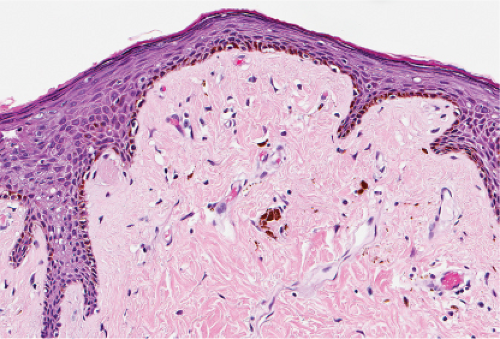

IIIA1e Superficial Perivascular Dermatitis, Melanophages Prominent

There is a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, with an admixture of pigment-laden melanophages, indicative of prior damage to the basal layer, and “pigmentary incontinence”. Some degree of residual interface damage may also be evident. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is a prototype (24).

Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation

Clinical Summary

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may follow any dermatitis that affects the dermal–epidermal junction and results in release of melanin pigment from basal keratinocytes into the dermis. Lichenoid dermatoses such as lichen planus, vacuolar dermatoses such as discoid lupus, or apoptotic/cytotoxic dermatoses such as erythema multiforme or fixed drug

eruptions may all result in this reaction pattern. Lesions are sometimes biopsied to rule out melanoma. If features diagnostic of a specific underlying dermatosis are lacking in the biopsy, the descriptive diagnosis of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may be all that can be made.

eruptions may all result in this reaction pattern. Lesions are sometimes biopsied to rule out melanoma. If features diagnostic of a specific underlying dermatosis are lacking in the biopsy, the descriptive diagnosis of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may be all that can be made.

Clin. Fig. IIIA1e. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. A 77-year-old man presented with macular brown changes in sites of previous lichen planus. |

Fig. IIIA1e.a. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, low power. There is an inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and melanophages. |

Histopathology

Sections show the phenomena of pigmentary incontinence. Melanin pigment deposited in the dermis is taken up by melanophages. These are large cells with abundant cytoplasm stuffed with pigment and with plump nuclei having open chromatin and sometimes a small nucleolus.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

post-chemotherapy hyperpigmentation

chlorpromazine pigmentation

amyloidosis

IIIA2 Superficial Perivascular Dermatitis, Mast Cells Predominant

Mast cells are the main infiltrating cells seen in the dermis. Lymphocytes are also present, and there may be a few eosinophils. Urticaria pigmentosa is the example.

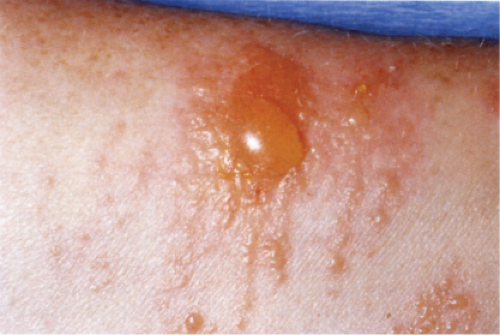

Urticaria Pigmentosa

Clinical Summary

Urticaria pigmentosa (25) can be divided into four forms: (1) urticaria pigmentosa arising in infancy or early childhood without significant systemic lesions, (2) urticaria pigmentosa arising in adolescence or adult life without significant systemic lesions, (3) systemic mast cell disease, and (4) mast cell leukemia. Five types of cutaneous lesions are seen. The maculopapular type, the most common, consists usually of dozens or even hundreds of small brown lesions that urticate on stroking; a second type exhibits multiple brown nodules or plaques,

and, on stroking, shows urtication and occasionally blister formation. A third type, seen almost exclusively in infants, is characterized by a usually solitary, large cutaneous nodule, which on stroking often shows not only urtication but also large bullae. The fourth type, the diffuse erythrodermic type, always starts in early infancy and shows generalized brownish red, soft infiltration of the skin, with urtication on stroking. The fifth type of lesion, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans (TMEP), which usually occurs in adults, consists of an extensive eruption of brownish red macules showing fine telangiectasias, with little or no urtication on stroking. Although mastocytosis is most typically a benign, self-limited disorder of childhood, up to 30% of adolescent and adult-onset disease represents cutaneous involvement by underlying systemic mastocytosis. CD25 immunoreactivity in a skin infiltrate may be a useful, though not specific, marker for systemic involvement (26).

and, on stroking, shows urtication and occasionally blister formation. A third type, seen almost exclusively in infants, is characterized by a usually solitary, large cutaneous nodule, which on stroking often shows not only urtication but also large bullae. The fourth type, the diffuse erythrodermic type, always starts in early infancy and shows generalized brownish red, soft infiltration of the skin, with urtication on stroking. The fifth type of lesion, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans (TMEP), which usually occurs in adults, consists of an extensive eruption of brownish red macules showing fine telangiectasias, with little or no urtication on stroking. Although mastocytosis is most typically a benign, self-limited disorder of childhood, up to 30% of adolescent and adult-onset disease represents cutaneous involvement by underlying systemic mastocytosis. CD25 immunoreactivity in a skin infiltrate may be a useful, though not specific, marker for systemic involvement (26).

Clin. Fig. IIIA2.a. Urticaria pigmentosa, nodular type. A 2–year-old had a recurrently erythematous and “swollen” solitary 2 cm yellow brown nodule on volar forearm. |

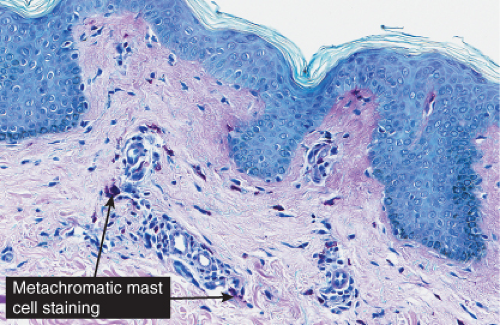

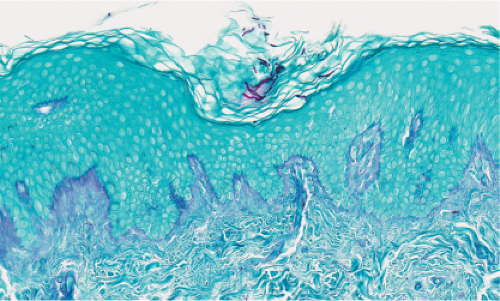

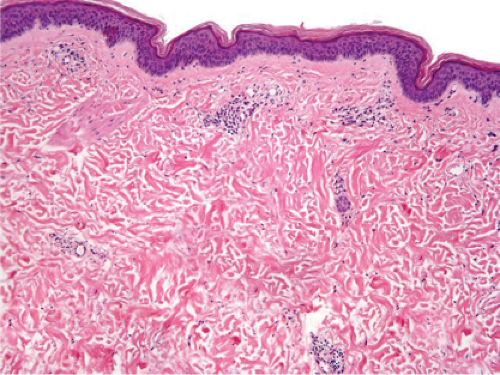

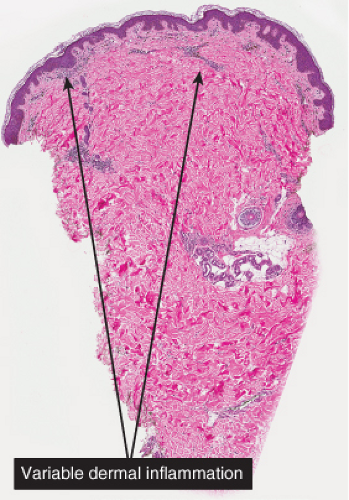

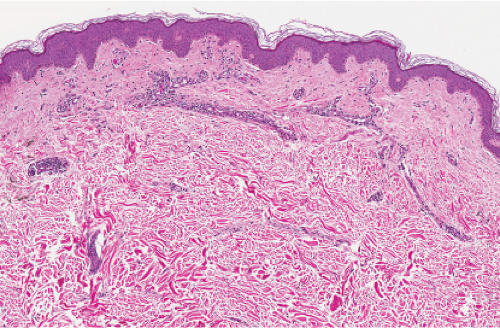

Fig. IIIA2.a. Adult mast cell disease (TMEP), low power. The epidermis is slightly acanthotic. There is a perivascular infiltrate of mononuclear cells about dermal vessels. |

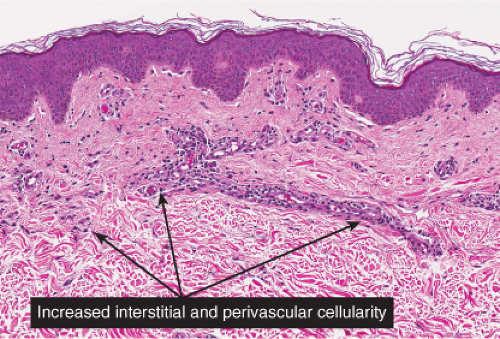

Fig. IIIA2.b. Adult mast cell disease, medium power. There is, in the dermis, a diffuse as well as perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and mast cells. |

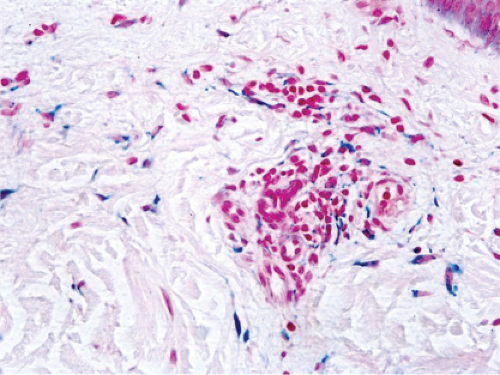

Fig. IIIA2.c. Adult mast cell disease, high power. Mast cells are seen about the thick-walled dermal vessels. |

Histopathology

In all five types of lesions, the histologic picture shows an infiltrate composed chiefly of mast cells, which are characterized by the presence of metachromatic granules in their cytoplasm. These granules can be visualized with a Giemsa or toluidine blue stain, or with the naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase reaction (Leder stain). The lesional cells are also positive with immunostains for KIT and mast cell tryptase (26). In the maculopapular type and in telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, the mast cells are limited to the upper third of the dermis and are generally located around capillaries. In some mast cells, the nuclei may be round or oval, but in most, they are spindle shaped. The diagnosis may be missed unless special staining is employed. In cases with multiple nodules or plaques or with a solitary large nodule, the mast cells lie closely packed in tumor-like aggregates and the infiltrate may extend into the subcutaneous fat. In the diffuse, erythrodermic type, there is a dense, band-like infiltrate of mast cells in the upper dermis. Eosinophils may be present in small numbers in all types of urticaria pigmentosa with the exception of TMEP, in which eosinophils are generally absent because of the small numbers of mast cells within the lesions.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

urticaria pigmentosa, nodular type

TMEP, adult mast cell disease

IIIB Superficial Dermatitis with Spongiosis (Spongiotic Dermatitis)

Spongiotic dermatitis is characterized by intercellular edema in the epidermis (27). In mild or early lesions, the intercellular space is increased with stretching of desmosomes but the integrity of the epithelium is intact. In more severe spongiotic conditions, there is separation of keratinocytes to form spaces (vesicles). For this reason, the spongiotic dermatoses are also listed below in Section IV. Acantholytic, Vesicular and Pustular Disorders.

1. Spongiotic Dermatitis, Lymphocytes Predominant

1a. Spongiotic Dermatitis, With Eosinophils

1b. Spongiotic Dermatitis, With Plasma Cells

1c. Spongiotic Dermatitis, With Neutrophils

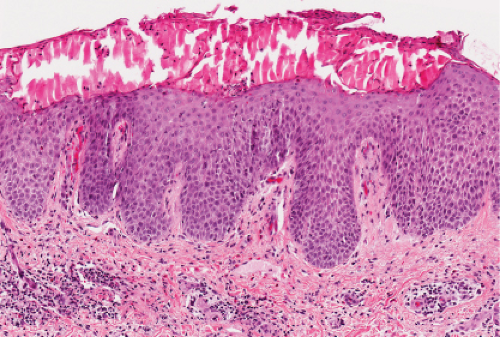

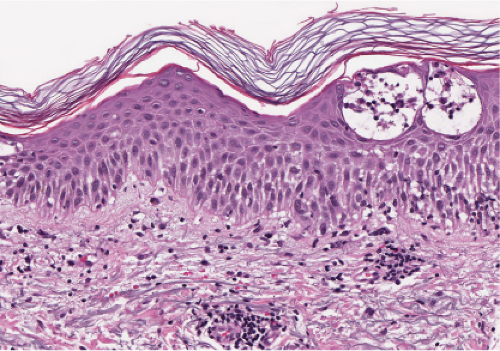

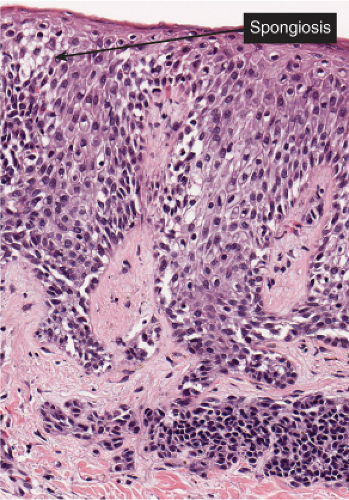

Acute Spongiotic Dermatitis

In acute spongiotic dermatitis (28), the stratum corneum is normal in a very early lesion, but there is slight hyperkeratosis in a somewhat later lesion. If the lesion persists, parakeratosis will develop as it evolves further. The epidermal keratinocytes are partially separated by intercellular edema, which stretches the intercellular bridges or desmosomes and renders them more prominent than normal. If the lesion is more severe, the desmosomal attachments rupture, and intercellular spaces appear, usually in the spinous layer, forming spongiotic vesicles. Lymphocytes and occasionally larger Langerhans histiocytes are present in the spaces and in the edematous epidermis. In addition, there is a loose perivascular infiltrate around the vessels of the superficial capillary-venular plexus.

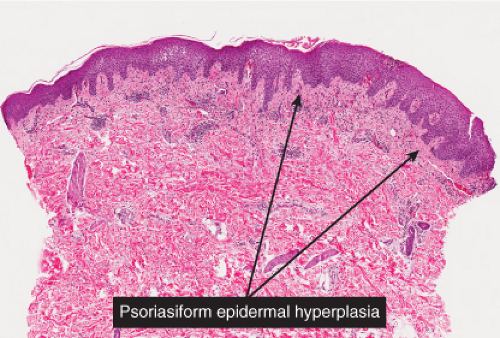

Subacute Spongiotic Dermatitis

In subacute spongiotic dermatitis, after a spongiotic lesion persists, there is epithelial hyperplasia, which tends to elongate the rete ridges in a pattern that is termed “psoriasiform”. Unlike in psoriasis, the suprapapillary plates of keratinocytes are not thinned, indeed they tend to be somewhat thickened. The etiology of the process is made apparent by the presence of spongiotic changes in the epidermis similar to those described above, though vesicle formation is often minimal. A similar perivascular infiltrate is present in the superficial dermis. Because the pattern of subacute spongiotic dermatitis is predominantly psoriasiform, these conditions are also discussed in section IIID, “psoriasiform dermatitis”.

Chronic Spongiotic Dermatitis

In chronic spongiotic dermatitis, there is prominent hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Spongiosis is usually present but may be quite inconspicuous in a given biopsy. Psoriasiform hyperplasia is prominent and when florid and complex may border on pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. A perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate is present and may include an admixture of histiocytes and even plasma cells, depending on the etiology of the condition. There is often a distinctive pattern of increased collagen fibers arranged vertically between the elongated rete ridges. This papillary dermis sclerosis may be attributable to chronic rubbing or scratching of the lesions, resulting in the condition termed lichen simplex chronicus, which may have as its underlying basis any of the chronic pruritic dermatoses.

The disorders listed below all tend to follow the course listed above, from an acute to a subacute to a chronic spongiotic dermatitis, if the condition persists, and depending on associated factors such as the severity of the condition, the effects of treatment, and the effects of added irritants including the presence of excoriations of chronic rubbing and scratching. The differential diagnosis suggested by a given biopsy specimen may vary to some extent as discussed below, depending for example on the admixture of cell types such as eosinophils or plasma cells, and on the patterns of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, and of papillary dermis sclerosis. However, in a given biopsy it is often difficult or impossible to distinguish among the various etiologic categories of spongiotic dermatitis. While a biopsy may be of value to rule out other competing possibilities, such as lymphoma, and may tend to favor one or another of the possibilities listed in the differential diagnosis tables, the exact classification of these disorders usually depends on clinicopathologic correlation.

IIIB1 Spongiotic Dermatitis, Lymphocytes Predominant

There is marked intercellular edema (spongiosis) within the epidermis. In the dermis, perivascular lymphocytes are predominant. Nummular dermatitis is prototypic.

Nummular Dermatitis (Eczema)

Clinical Summary

The eruption is characterized by pruritic, coin-shaped (nummular), erythematous, scaly, crusted plaques. The lesions tend to develop on the extensor surfaces of the extremities. Hypersensitivity to haptens such as metals may be involved in the pathogenesis of nummular dermatitis in some patients (29).

Histopathology

Nummular dermatitis is the prototype of acute and subacute spongiotic dermatitis. There is mild to moderate spongiosis, usually without vesiculation, and a superficial perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and occasional eosinophils. The epidermis is moderately acanthotic and parakeratotic. The stratum corneum contains aggregates of coagulated plasma and scattered neutrophils, forming a crust. Mild papillary dermal edema and vascular dilatation may be present.

Eczematous dermatitis.

Clinical Summary

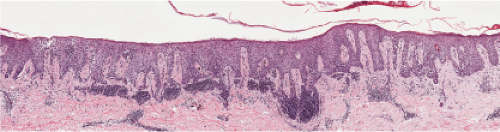

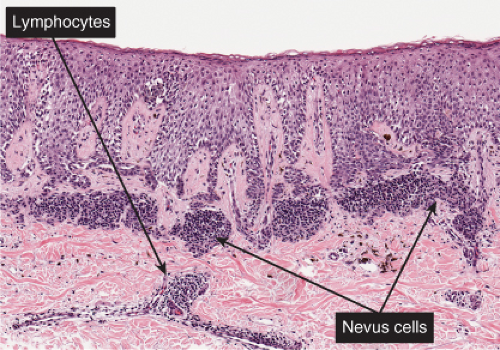

Meyerson’s nevus is a melanocytic nevus that is associated with an erythematous, eczematous halo that may symmetrically or eccentrically encircle the nevus (30). The lesion may be pruritic and scaly. Spontaneous resolution of the eczema over the course of weeks, without disappearance of the nevus, usually occurs. Meyerson’s nevi usually occur on the trunk and are more common in males. The simultaneous appearance of a Sutton’s (halo) nevus and Meyerson’s nevus has been reported after sunburn, as has the subsequent development of a Sutton’s nevus and vitiligo 6 months after removal of a Meyerson’s nevus, but this is not typical. Interferon-alpha therapy has been shown to induce Meyerson’s nevus (31).

Histopathology

The melanocytic nevus may be banal, congenital (32), or dysplastic (33), with superimposed

changes of an eczematous dermatitis characterized by epidermal acanthosis and spongiosis which encompass the nevus and the adjacent epidermis (the eczematous halo). Spongiotic intraepidermal vesicles and eosinophilic spongiosis may be present. The stratum corneum may show focal parakeratosis with collections of serum. The superficial dermal infiltrate is composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. The lymphocytes have been shown to be predominantly CD4+ (helper) T cells, in contrast to the CD8+ (suppressor) T cells that are found in halo nevi.

changes of an eczematous dermatitis characterized by epidermal acanthosis and spongiosis which encompass the nevus and the adjacent epidermis (the eczematous halo). Spongiotic intraepidermal vesicles and eosinophilic spongiosis may be present. The stratum corneum may show focal parakeratosis with collections of serum. The superficial dermal infiltrate is composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. The lymphocytes have been shown to be predominantly CD4+ (helper) T cells, in contrast to the CD8+ (suppressor) T cells that are found in halo nevi.

Clin. Fig. IIIB1.a. Former Clin. Fig. IIIB1. Nummular eczema. A crusted, coin-shaped plaque with serous exudate on the extensor surface of the lower extremity typifies this pruritic, episodic condition. |

Fig. IIIB1.c. Acute spongiotic dermatitis, high power. The epidermal keratinocytes are partially separated by edema (spongiosis), stretching the intercellular desmosomes. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

eczematous dermatitis

atopic dermatitis

allergic contact dermatitis

photoallergic drug eruption

irritant contact dermatitis

nummular eczema

dyshidrotic dermatitis

Meyerson’s nevus

parapsoriasis, small plaque type (digitate dermatosis)

Clin. Fig. IIIB1.b. Meyerson’s nevus. Note the “eczematous” reaction surrounding the atypical nevus.

Fig. IIIB1.d. Meyerson’s nevus, low power. The epidermis is acanthotic, spongiotic, and surmounted by parakeratotic scale with collections of serum.

Fig. IIIB1.e. Meyerson’s nevus, low power. A mononuclear cell inflammatory infiltrate is present in the upper dermis, predominantly around vessels. Nevus cells are inconspicuous.

Fig. IIIB1.g. Meyerson’s nevus, high power. There is intense spongiosis in the epidermis. Nested nevus cells are seen in the dermis.

polymorphous light eruption

lichen striatus

chronic actinic dermatitis (actinic reticuloid)

actinic prurigo, early lesions

“id” reaction

seborrheic dermatitis

stasis dermatitis

erythroderma

miliaria

pityriasis rosea

Sezary syndrome

papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti-Crosti)

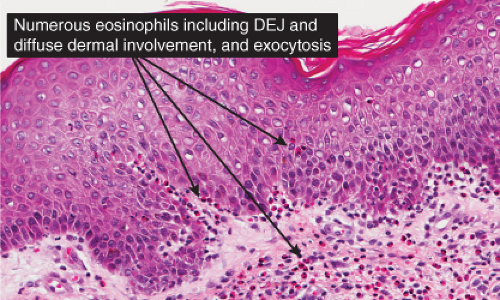

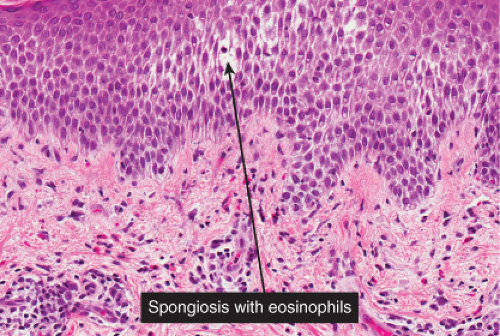

IIIB1a Spongiotic Dermatitis, with Eosinophils

There is marked intercellular edema (spongiosis) within the epidermis. In the dermis, lymphocytes are predominant. Eosinophils can be found in most examples of atopy, and allergic contact dermatitis, and are numerous in incontinentia pigmenti. Allergic contact dermatitis is the prototype (27).

Clin. Fig. IIIB1a.a. Allergic contact dermatitis. Vesicles and bullae developed on volar forearm after application of perfume. |

Fig. IIIB1a.b. Acute allergic contact dermatitis, high power. Tense spongiotic vesicles are formed by the confluence of spongiotic intercellular edema. |

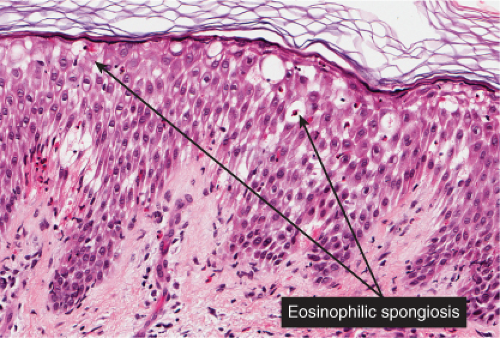

Fig. IIIB1a.c. Acute allergic contact dermatitis, high power. The epidermis is spongiotic with a diffuse infiltrate of eosinophils (eosinophilic spongiosis). |

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Clinical Summary

The prototype of acute spongiotic dermatitis is allergic contact dermatitis, for example as a reaction to poison ivy exposure. Usually between 24 and 72 hours after exposure to the antigen, the patient develops pruritic, edematous, erythematous papules and plaques and, in some cases, vesicles. Linear papules and vesicles are common in allergic contact dermatitis to poison ivy, reflecting the points of contact between the plant and the skin. Markers of genetic susceptibility to contact allergy are beginning to be identified (34).

Histopathology

Early lesions are an acute spongiotic dermatitis. If vesicles develop, they may contain clusters of Langerhans cells. Eosinophils may be present in the dermal infiltrate as well as within areas of spongiosis. In patients with continued exposure to the antigen, the biopsy may show a subacute or later a chronic spongiotic dermatitis, often lichen simplex chronicus due to rubbing. In a recent study, eosinophilic spongiosis and multinucleate dermal dendritic fibrohistiocytic cells, in the presence of acanthosis, lymphocytic infiltrate, dermal eosinophils, and hyperkeratosis, were considered to be particularly suggestive of allergic contact dermatitis compared to other spongiotic dermatoses (27).

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

spongiotic (eczematous) dermatitis

atopic dermatitis

allergic contact dermatitis

photoallergic drug eruption

incontinentia pigmenti, vesicular stage

eczematous nevus (Meyerson’s nevus)

erythema gyratum repens

scabies

erythema toxicum neonatorum

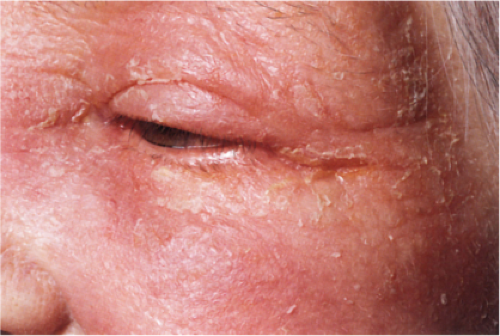

Clin. Fig. IIIB1a.b. Subacute contact dermatitis. Elderly woman had several month history of pruritic scaly facial erythema and positive fragrance mix patch test. |

Fig. IIIB1a.e. Subacute allergic contact dermatitis, medium power. The epidermis is spongiotic. There is an inflammatory infiltrate in the edematous papillary dermis. |

IIIB1b Spongiotic Dermatitis, with Plasma Cells

There is marked intercellular edema (spongiosis) within the epidermis. In the dermis, perivascular lymphocytes are predominant, and plasma cells are present. Syphilis is the prototype (see Section IIIA1c.a–c).

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

syphilis, primary or secondary lesions

pinta, primary or secondary lesions

seborrheic dermatitis in HIV

IIIB1c Spongiotic Dermatitis, with Neutrophils

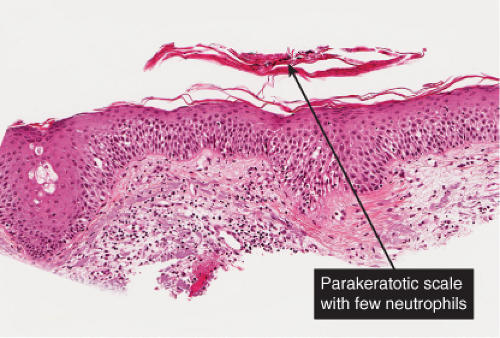

There is marked intercellular edema (spongiosis) within the epidermis. Lymphocytes are present in the dermis. There is focal and shoulder parakeratosis, with a few neutrophils in the stratum corneum. Seborrheic dermatitis is a prototype (35).

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Clinical Summary

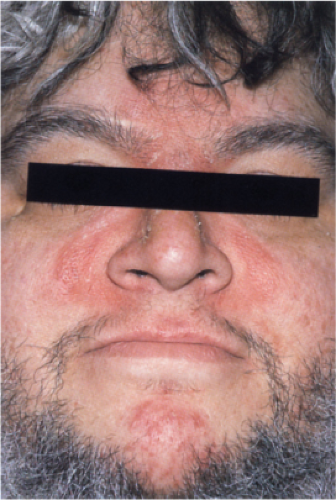

Clinically, patients develop erythema and greasy scale on the scalp, paranasal areas, eyebrows, nasolabial folds, and central chest. Rarely, patients with seborrheic dermatitis develop generalized lesions. Patients with HIV infection often have severe, recalcitrant disease (2). In infants, the scalp (“cradle cap”), face, and diaper areas are often involved.

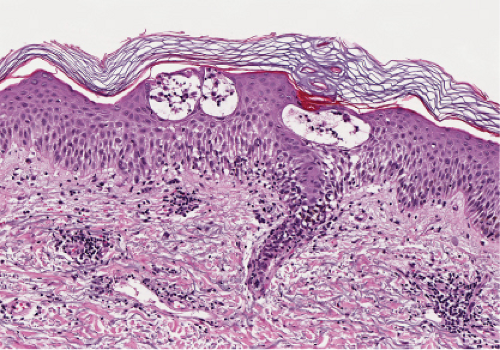

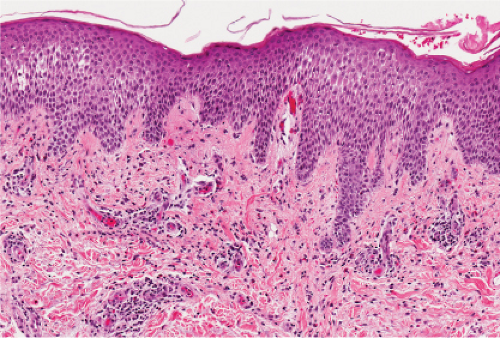

Histopathology

The histopathologic features are a combination of those observed in psoriasis and spongiotic dermatitis. Mild cases may exhibit only a slight subacute spongiotic dermatitis. The stratum corneum contains focal areas of parakeratosis, with a predilection for the follicular ostia, a finding known as “shoulder parakeratosis.” Occasional pyknotic neutrophils are present within parakeratotic foci. There is moderate acanthosis with regular elongation of the rete ridges, mild spongiosis, and focal exocytosis of lymphocytes. The dermis contains a sparse mononuclear cell infiltrate. In HIV-infected patients, the epidermis may contain dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and the dermal infiltrate may contain plasma cells.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

dermatophytosis

seborrheic dermatitis

toxic shock syndrome

Clin. Fig. IIIB1c. Seborrheic dermatitis. Greasy erythema involving the nasolabial folds, glabella, medial eyebrows and chin characterize this condition. |

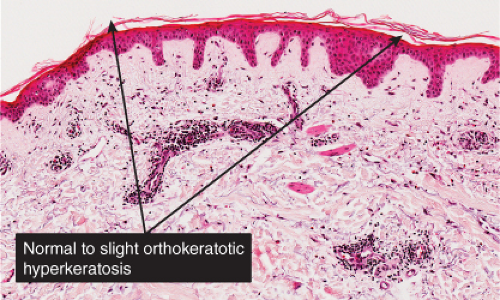

Fig. IIIB1c.a. Seborrheic dermatitis, medium power. An ortho and parakeratotic scale overlie an acanthotic epidermis that also has spongiosis and exocytosis. |

IIIC Superficial Dermatitis with Epidermal Atrophy (Atrophic Dermatitis)

Most inflammatory dermatoses are associated with epithelial hyperplasia. Only a few chronic conditions exhibit epidermal atrophy.

1. Atrophic Dermatitis, Scant Inflammatory Infiltrates.

2. Atrophic Dermatitis, Lymphocytes Predominant

2a. Atrophic Dermatitis With Papillary Dermal Sclerosis

IIIC1 Atrophic Dermatitis, Scant Inflammatory Infiltrates

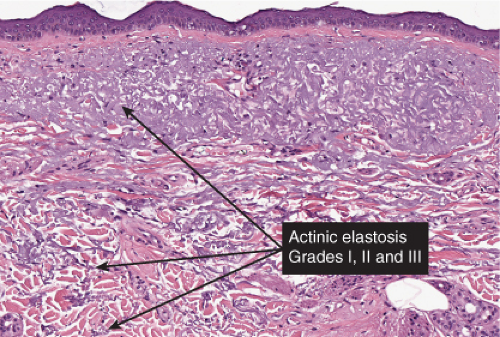

The epidermis is thinned, only a few cell layers thick. There is a scanty lymphocytic infiltrate about the superficial capillary-venular plexus. Aged skin is the prototype (36).

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

aged skin

chronic actinic damage

radiation dermatitis

porokeratosis

acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans

malignant atrophic papulosis

poikiloderma atrophicans vasculare

Aged Skin

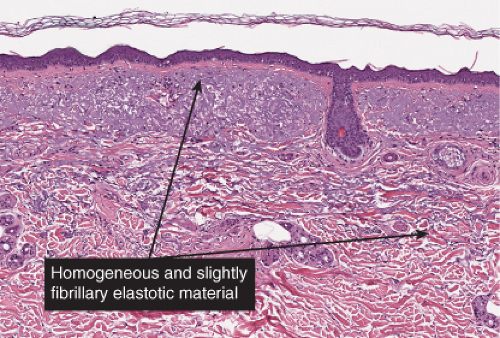

Although not an inevitable consequence of aging in the skin, actinic elastosis is a prominent feature in the sun-exposed skin of susceptible individuals. A validated grading scheme for actinic elastosis has been described (37).

Radiation Dermatitis (See also Section VF1)

See Fig. IIIC1.c and Fig. IIIC1.d.

Clin. Fig. IIIC1. Aged skin. Dorsal hand has transparent, wrinkled skin with prominent vessel and solar purpura. |

Fig. IIIC1.a. Aged skin, low power. There is aneffaced atrophic epidermis. The dermis shows marked solar elastosis with dilated thin walled vessels. The inflammatory infiltrate is sparse. |

IIIC2 Atrophic Dermatitis, Lymphocytes Predominant

The epidermis is thinned, but not as marked as in aged or irradiated skin. In the dermis there are few to many lymphocytes about the superficial capillary-venular plexus.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

parapsoriasis/early mycosis fungoides

lupus erythematous

mixed connective tissue disease

pinta, tertiary lesions

dermatomyositis

poikiloderma atrophicans vasculare

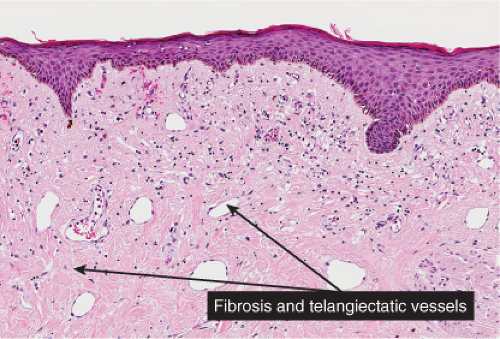

Poikiloderma Atrophicans Vasculare

Clinical Summary

Clinically, the term poikiloderma atrophicans vasculare is applied to lesions that, in the early stage, show erythema with slight, superficial scaling, a mottled pigmentation, and telangiectases. In the late stage the skin appears atrophic and the mottled pigmentation and the telangiectases are more pronounced. The condition may be seen in three different settings: (1) in association with certain genodermatoses; (2) as an early stage of mycosis fungoides (38); and (3) in association with dermatomyositis and, less commonly, lupus erythematosus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree