Perivascular, Diffuse and Granulomatous Infiltrates of the Reticular Dermis

|

The dermis serves as a reaction site for a variety of inflammatory, infiltrative, and desmoplastic processes. These include infiltrations of a variety of cells (lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, melanocytes, etc.); perivascular and vascular reactions; infiltration with organisms and foreign bodies; proliferations of dermal fibers and precursors of dermal fibers as reactions to a variety of stimuli.

VA Superficial and Deep Perivascular Infiltrates Without Vasculitis

In some of the diseases considered here, the infiltrates are predominantly in the upper reticular dermis (urticarial eruptions), while others are both superficial and deep (gyrate erythemas). Most of these also involve the superficial plexus. A few diseases are mainly deep (some examples of lupus erythematosus, scleroderma).

Perivascular Infiltrates, Lymphocytes Predominant

Perivascular Infiltrates, Neutrophils Predominant

Perivascular Infiltrates, Lymphocytes and Eosinophils

Perivascular Infiltrates, with Plasma Cells

Perivascular Infiltrates, Mixed Cell Types

VA1 Perivascular Infiltrates, Lymphocytes Predominant

In the dermis, there is no vasculitis, only perivascular collections of lymphocytes as the predominant cell. Erythema annulare centrifigum (EAC) is prototypic (1,2).

Erythema Annulare Centrifugum

Clinical Summary

Also known as gyrate erythema, this disorder represents a hypersensitivity reaction manifesting as arcuate and polycyclic areas of erythema. The condition has been categorized into superficial and deep variants. The deep form is characterized clinically by annular areas of palpable erythema with central clearing and absence of surface changes. The superficial variant differs only by the presence of a characteristic trailing scale, a delicate annular rim of scale that trails behind the advancing edge of erythema. Small vesicles may occur. The lesions may attain considerable size (up to 10 cm across) over a period of several weeks, may be mildly pruritic, and have a predilection for the trunk and proximal extremities. Erythema annulare centrifugum can be considered a reactive phenomenon, and has been associated with a variety of disparate conditions including pregnancy, surgical procedures, breast cancer, lymphoma, leukemia, herpes zoster, medication reactions, as well as others. Most cases resolve spontaneously within 6 weeks; however, the condition may persist for years.

Histopathology

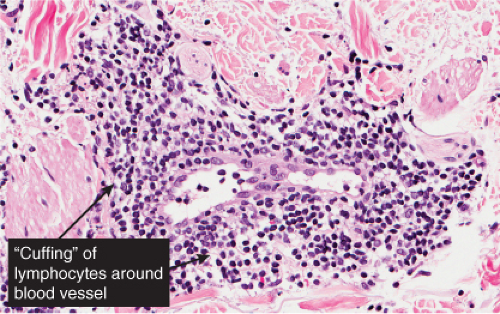

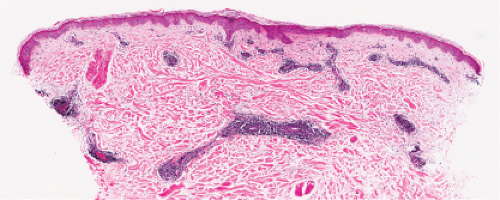

In the classic deep or indurated type, a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate characterized by a tightly cuffed “coat-sleeve–like” pattern is present in the middle and lower portions of the dermis. In the superficial variant, there is a superficial perivascular tightly cuffed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with endothelial cell swelling and focal extravasation of erythrocytes in the papillary dermis, and focal epidermal spongiosis and parakeratosis can be seen. Erythema chronicum migrans (ECM) is an important differential, but often presents with plasma cells as well as lymphocytes and is therefore discussed also in VA4.

Tumid Lupus Erythematosus

The dermal form of LE without surface/epithelial changes is known as tumid LE. Clinically, affected patients display

indurated papules, plaques, and nodules without erythema, atrophy, or ulceration of the surface. Histologically, superficial and deep dermal perivascular, interstitial, and periappendageal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates associated with stromal mucin deposits are observed (3).

indurated papules, plaques, and nodules without erythema, atrophy, or ulceration of the surface. Histologically, superficial and deep dermal perivascular, interstitial, and periappendageal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates associated with stromal mucin deposits are observed (3).

Clin. Fig. VA1.a. Erythema annulare centrifigum. Multiple annular lesions developed on the trunk of a middle-aged man. |

Clin. Fig. VA1.b. Erythema annulare centrifigum. An annular area of palpable erythema with central clearing and a delicate annular rim of scale trailing behind the advancing edge of the erythema. |

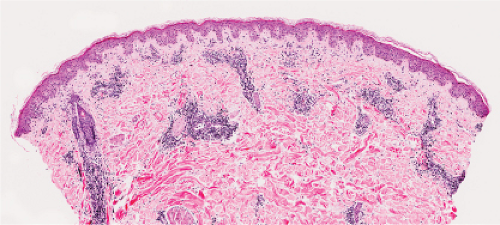

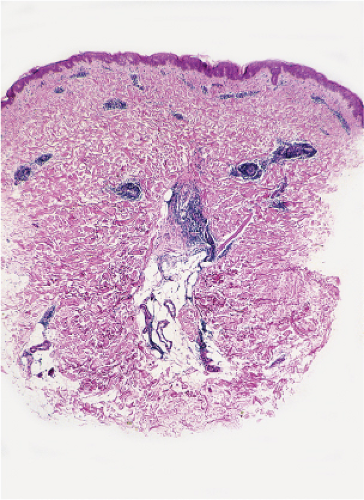

Fig. VA1.a. Erythema annulare centrifigum, low power. A tight cuff of small round cells surrounds the vessels of the superficial and mid-dermal plexuses. |

Fig. VA1.b. Erythema annulare centrifigum, medium power. The vessels at the center of the infiltrates show no evidence of damage other than slight endothelial cell swelling. |

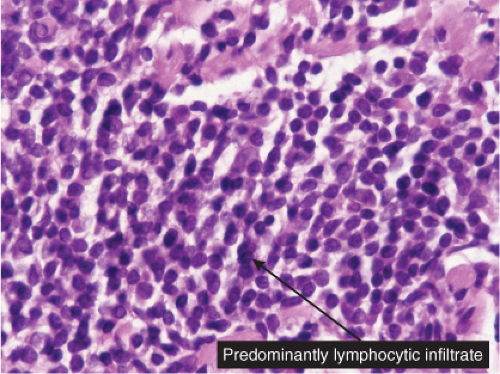

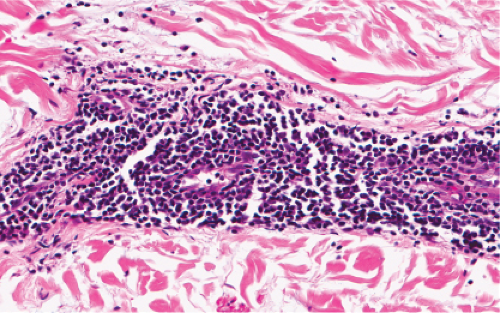

Fig. VA1.c. Erythema annulare centrifigum, high power. The infiltrate is composed almost entirely of mature small lymphocytes. |

Clin. Fig. VA1.c. Erythema chronicum migrans. Note the central bite area and expanding border of erythema in a confirmed case of Lyme disease. |

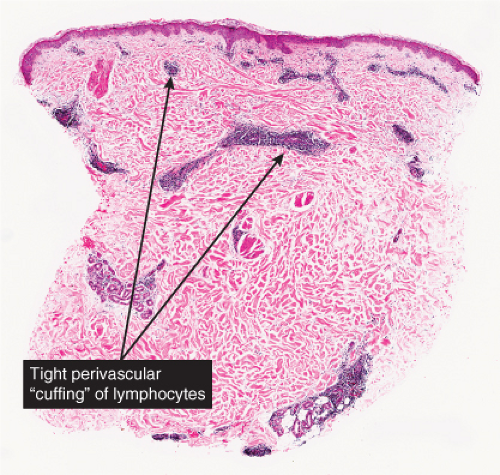

Fig. VA1.d. Erythema chronicum migrans, low power. Similar to EAC, there is a tight cuff of small cells around the vessels of the superficial and deep-dermal plexuses. |

Fig. VA1.e. Erythema chronicum migrans, medium power. The infiltrate surrounds vessels quite tightly, without a significant interstitial infiltrate. |

Fig. VA1.f. Erythema chronicum migrans, high power. Although plasma cells are usually present, in some instances, as here, the infiltrate is composed almost entirely of mature small lymphocytes. |

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA)

stasis dermatitis

acne rosacea

Clin. Fig. VA1.d. Tumid lupus. This is a deeper and more nodular form of lupus that presents with little to no scale. Some consider it a variant of subacute cutaneous lupus.

discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE)

polymorphous light eruption

deep gyrate erythemas

erythema annulare centrifigum

erythema chronicum migrans

Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate

reticulated erythematous mucinosis (REM)

perioral dermatitis

papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti–Crosti)

leprosy, indeterminant

“tumid” lupus erythematosus

perniosis (chilblains)

VA2 Perivascular Infiltrates, Neutrophils Predominant

In this pattern, neutrophils are seen in perivascular or perivascular and diffuse patterns in the dermis. Edema is prominent in some instances. Sweet’s syndrome can present as a perivascular infiltrate, but is more often nodular and is therefore discussed in section VC2. Neutrophil-rich urticaria may present as a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate, but eosinophils are usually also present (see section VA3). The other conditions listed are mostly infections. Biopsies from the periphery of a lesion may appear perivascular, but the fully developed center of these lesions will consist of diffuse infiltrates (section VA3).

Cellulitis

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s)

erysipelas

necrotizing fasciitis

Clin. Fig. VA2. Cellulitis. This middle-age female was admitted with septic shock secondary to her cellulitis. She had marked erythema and bullous changes and rapidly improved on IV antibiotics.

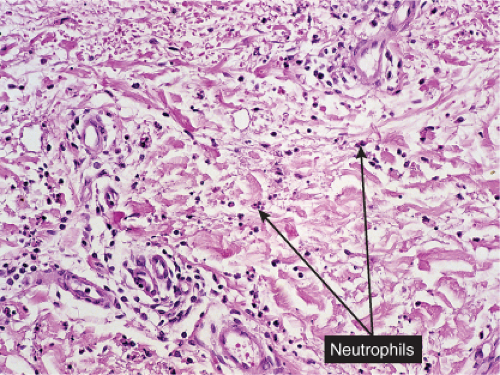

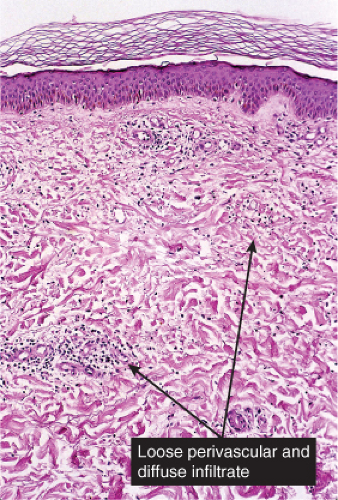

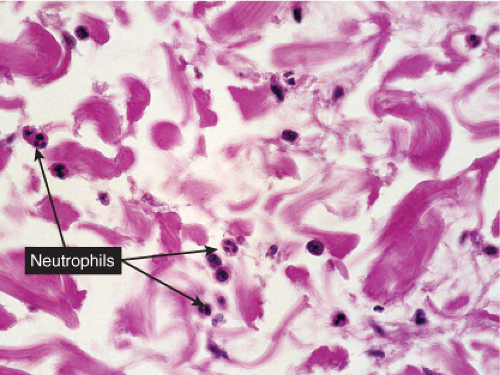

Fig. VA2.a. Cellulitis, low power. There is edema and a patchy infiltrate in the reticular dermis, appearing at this magnification to be mainly perivascular.

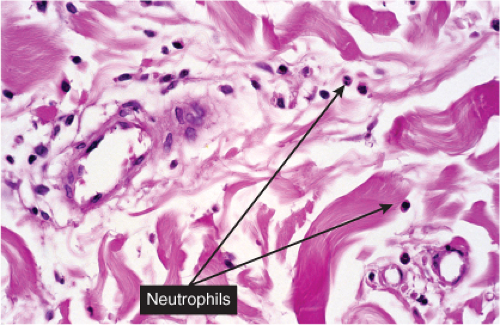

Fig. VA2.b. Cellulitis, high power. The cells about the vessels are mainly neutrophils. In other areas, the infiltrate appears more diffuse (see VC2).

pyoderma gangrenosum (early)

ecthyma gangrenosum

neutrophil-rich urticaria

solar urticaria

rheumatoid arthritis

neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands

other neutrophilic dermatoses

Behçet disease

Bowel bypass syndrome (Bowel-associated dermatosis–arthritis syndrome)

Erythema elevatum diutinum

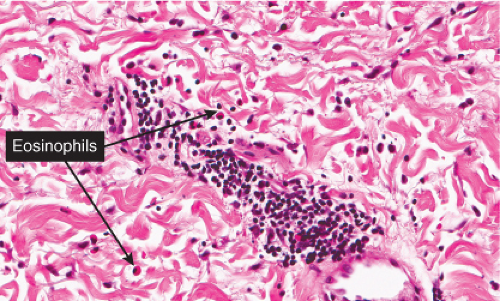

VA3 Perivascular Infiltrates, Lymphocytes and Eosinophils

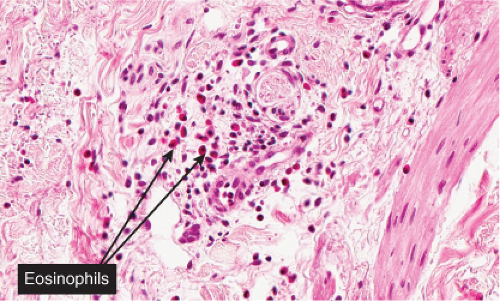

Lymphocytes and eosinophils are mixed in the infiltrate. Lymphocytes are always seen, eosinophil numbers may vary being greatest in bite reactions and often (though variable and sometimes very few) in eosinophilic fasciitis. Papular urticaria is a prototypic example (4).

Papular Urticaria

Clinical Summary

Also known as lichen urticatus, this condition is the result of hypersensitivity to bites from certain insects, especially mosquitoes, fleas, and bedbugs. One observes edematous papules and papulovesicles, which, because of severe itching, usually are excoriated. The eruption is more common in children than adults, and, if caused by mosquitoes, is limited to the summer months.

Histopathology

The stratum malpighii shows intercellular and intracellular edema and occasionally a spongiotic vesicle. A predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate is present around the vessels of the dermis, often extending into the lower dermis and containing a significant admixture of eosinophils.

Urticaria

Clinical Summary

Urticaria is characterized by the presence of abrupt onset, transient and recurrent wheals, which are raised erythematous and edematous areas of skin that are often pruritic. When large wheals occur and the edema extends to the subcutaneous or submucosal tissues, the process is referred to as angioedema. Acute episodes of urticaria generally last only several hours. When episodes of urticaria last up to 24 hours and recur over a period of at least six to eight weeks, the condition is considered chronic urticaria. The various causes of urticaria include soluble antigens in foods, drugs, insect venom; contact allergens; physical stimuli such as pressure, vibration, solar radiation, cold temperature; occult infections and malignancies; and some hereditary syndromes, but in many cases the cause remains undetermined.

Fig. VA3.a. Papular urticaria/arthropod bite, low power. A dense perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils, more conspicuous than in many instances of typical “papular urticaria.” |

Fig. VA3.b. Papular urticaria/arthropod bite, medium power. The infiltrate shows both a perivascular and interstitial pattern. |

Clin. Fig. VA3. Urticaria. Edematous plaques with central clearing and geographic configuration are typical of urticaria. |

Fig. VA3.d. Urticaria, low power. A patchy perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils, which could be seen in “papular urticaria” or in idiopathic urticaria. |

Fig. VA3.e. Urticaria, medium power. There is sparse dermal edema separating collagen fibers. Lymphatic channels are dilated (a clue to the presence of edema). |

Fig. VA3.f. Urticaria, high power. The perivascular infiltrate includes mostly eosinophils and neutrophils. This density of infiltrate is compatible with chronic urticaria. |

Fig. VA3.g. Pruritic & urticarial papules & plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), low power. There is a tight perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils about the superficial and mid plexuses. |

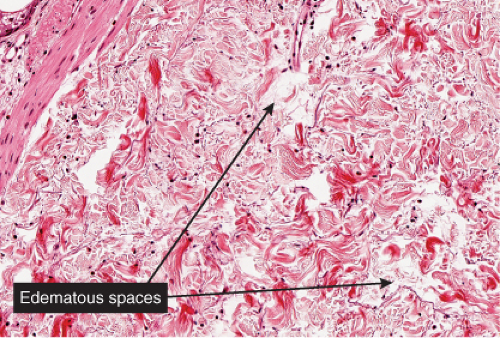

Fig. VA3.h. PUPPP, medium power. As in usual urticaria, there is dermal edema separating collagen fibers, and lymphatic channels are dilated. |

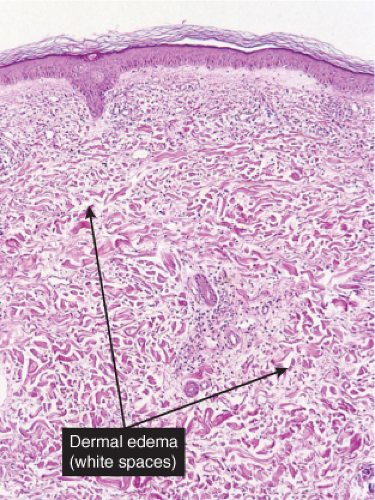

Histopathology

In acute urticaria, the prominent feature is interstitial dermal edema, with dilated lymphatics and venules with endothelial swelling, and a paucity of inflammatory cells. In chronic urticaria, interstitial dermal edema and a perivascular and interstitial mixed-cell infiltrate with variable numbers of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present.

Pruritic Urticarial Papules and Plaques of Pregnancy

Clinical Summary

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) is a fairly common entity that has a predilection for primigravidas in the third trimester of pregnancy (5). It can also occur directly post partum. PUPPP is associated with excessive maternal weight gain and multiple pregnancies. The rash usually starts on the abdomen and is composed of intensely pruritic erythematous urticarial papules, which may be surmounted by vesicles. The proximal parts of the extremities are also affected. There is no increased incidence of the rash in subsequent pregnancies. Typically lesions begin within striae distensae, and sparing of the umbilical area is a characteristic finding (as opposed to pemphigoid gestationis. The rash usually involutes spontaneously after delivery. Fetal outcome appears to be unaffected. The skin of the newborn child is unaffected (6).

Histopathology

Microscopic findings most commonly show a superficial and mid-dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with variable numbers of eosinophils and neutrophils together with edema of the superficial dermis. Epidermal involvement is variable and consists of focal spongiosis with exocytosis, parakeratosis, and mild acanthosis.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

urticaria/angioedema

pruritic & urticarial papules & plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP)

prurigo simplex

papular urticaria

morbilliform drug eruption

photoallergic reaction

eosinophilic fasciitis/scleroderma

angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (AHLE)

insect bite reaction

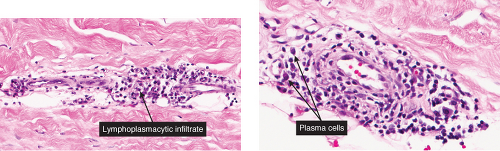

VA4 Perivascular Infiltrates, with Plasma Cells

In addition to lymphocytes, plasma cells are found in the dermal infiltrate. Secondary syphilis is a prototypic example (7).

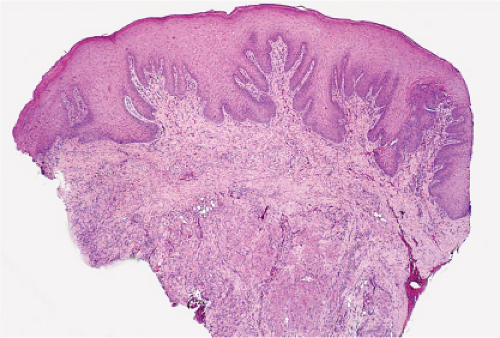

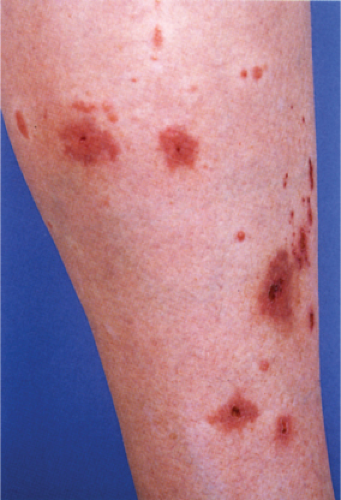

Secondary Syphilis

Secondary syphilis results from the hematogenous dissemination of Treponema. Pallidum, resulting in widespread clinical signs accompanied by constitutional symptoms inclusive of fever, malaise, and generalized lymphadenopathy. A generalized eruption occurs, comprising brown-red macules and papules, and, rarely, pustules. Lesions may be follicular, annular, or serpiginous. Other skin findings include alopecia and condylomata lata, the latter comprising broad, raised, gray, confluent papular lesions arising in anogenital areas, and mucous patches composed of multiple shallow, painless ulcers. Scaling macules or papules on the palms and soles are a characteristic feature, and this is also known as a “copper penny” rash.

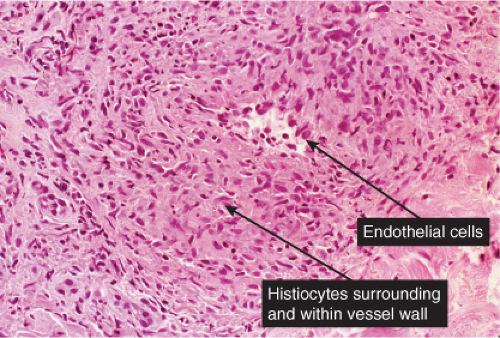

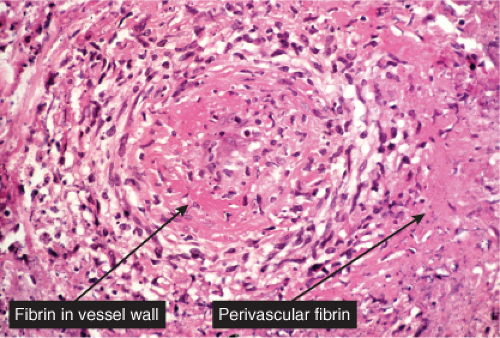

Histopathology

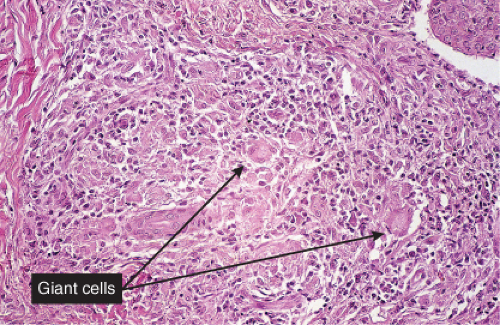

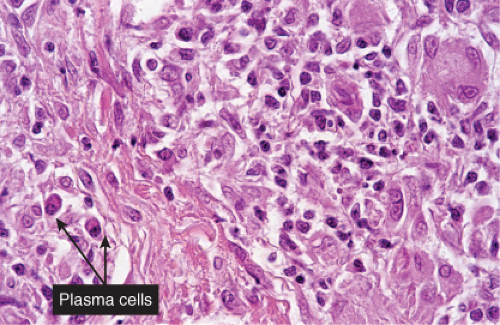

The two fundamental pathologic changes in syphilis are (1) swelling and proliferation of endothelial cells and (2) a predominantly perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphoid cells and often plasma cells. However, plasma cells and endothelial swelling are not invariably present. Frank necrotizing vasculitis is distinctly unusual. In late secondary and tertiary syphilis,

there are also granulomatous infiltrates of epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells.

there are also granulomatous infiltrates of epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells.

Clin. Fig. VA4.a. Secondary syphilis. This HIV positive male presented with annular papules on his penis. |

Clin. Fig. VA4.b. Secondary syphilis. Brown-red macules were present on his palms. RPR was positive. |

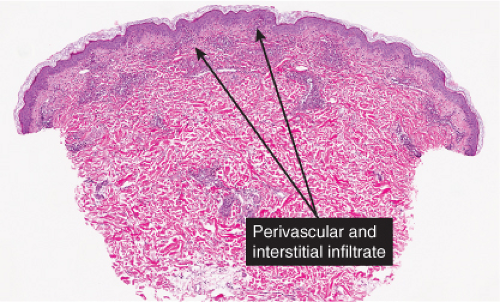

Fig. VA4.a. Secondary syphilis, low power. There is hyperplasia of the epidermis with In the dermis, there is a perivascular to diffuse infiltrate of mixed cell types. |

Fig. VA4.d. Secondary syphilis, high power. A mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, often also including neutrophils and eosinophils is present. |

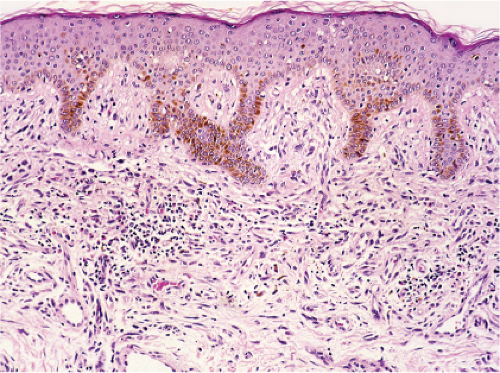

Biopsies generally reveal psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with spongiosis and basilar vacuolar alteration, exocytosis of lymphocytes, spongiform pustulation, and parakeratosis. The parakeratosis may be patchy or broad, with or without intracorneal neutrophilic abscesses. Scattered necrotic keratinocytes may be observed. Ulceration is not usual except in lues maligna. The dermal changes include marked papillary dermal edema and a perivascular and/or periadnexal and often lichenoid infiltrate that may be lymphocyte predominant, lymphohistiocytic, histiocytic predominant, or frankly granulomatous and that is of greatest intensity in the papillary dermis and extends as loose perivascular aggregates into the reticular dermis. In a few cases, atypical-appearing nuclei may be present and may suggest the possibility of lymphoma. Neutrophils are not infrequent and may permeate the eccrine coil to produce a neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Granulomatous inflammation develops after a few months. A silver stain is positive for spirochetes in about a third of the cases. Silver stains can be difficult to interpret because of high background. In addition, positive results do not necessarily indicate the presence of Treponema Pallidum as a silver stain is not specific for this organism. Immunohistochemistry using antibodies directed against Treponema Pallidum Antigen have been shown to be more sensitive than silver stains and reflect a new standard for adjunct histological testing. PCR analysis is another technique which is valuable for the detection of Treponema

Pallidum (8,9,10). The organisms are seen in the epidermis, follicular epithelium, and blood vessels. Lesions of condylomata lata show all of the aforementioned changes, but with more florid epithelial hyperplasia and intraepithelial microabscess formation.

Pallidum (8,9,10). The organisms are seen in the epidermis, follicular epithelium, and blood vessels. Lesions of condylomata lata show all of the aforementioned changes, but with more florid epithelial hyperplasia and intraepithelial microabscess formation.

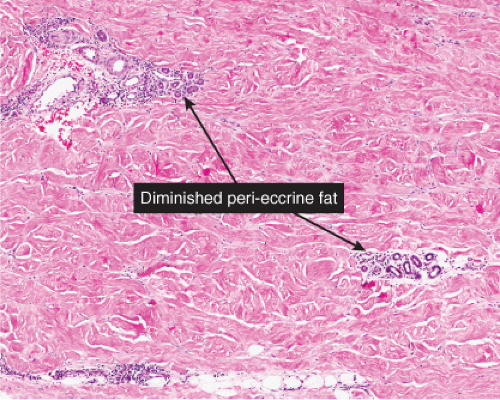

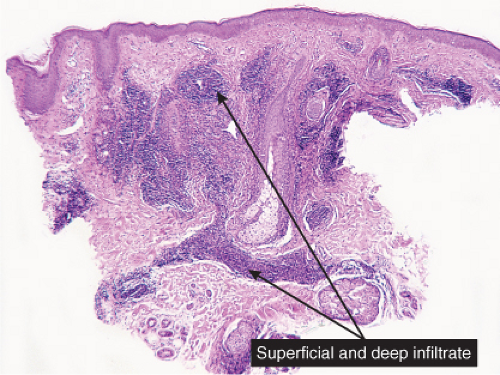

Morphea (See also VF)

See Figs. VA4.e–h.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

primary syphilitic chancre

erythema chronicum migrans

acne rosacea

perioral dermatitis

scleroderma/morphea

secondary syphilis

Kaposi’s sarcoma, early lesions

Fig. VA4.f. Morphea, medium power. Inflammatory stage morphea may present as a perivascular dermatitis. |

VA5 Perivascular Infiltrates, Mixed Cell Types

In addition to lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils are found in the dermal infiltrate. Erythema chronicum migrans is a prototypic example (11).

Erythema Chronicum Migrans

Clinical Summary

Erythema chronicum migrans is the distinctive cutaneous manifestation of stage I Lyme disease and represents the site of primary tick inoculation. The lesion starts as an area of scaly erythema or a distinct

red papule within 3 to 30 days after the tick bite, before spreading centrifugally with central clearing after a few weeks, occasionally reaching a diameter of 25 cm. Average lesional duration is a few weeks but in some cases, lesions may persist for as long as 12 months. The lesions may be solitary or multiple, the latter reflecting hematogenous dissemination of the spirochete, which may be accompanied by fever, fatigue, headaches, cough, and arthralgias.

red papule within 3 to 30 days after the tick bite, before spreading centrifugally with central clearing after a few weeks, occasionally reaching a diameter of 25 cm. Average lesional duration is a few weeks but in some cases, lesions may persist for as long as 12 months. The lesions may be solitary or multiple, the latter reflecting hematogenous dissemination of the spirochete, which may be accompanied by fever, fatigue, headaches, cough, and arthralgias.

Fig. VA5.a. Erythema chronicum migrans, low power. There is a tight cuff of small round cells about the vessels of the superficial and mid-dermal plexuses. |

Histopathology

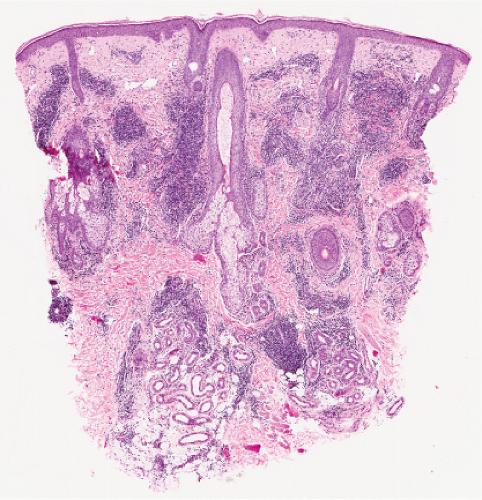

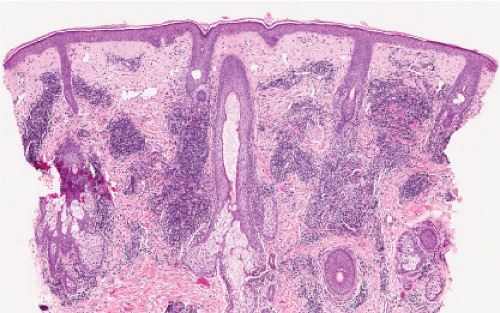

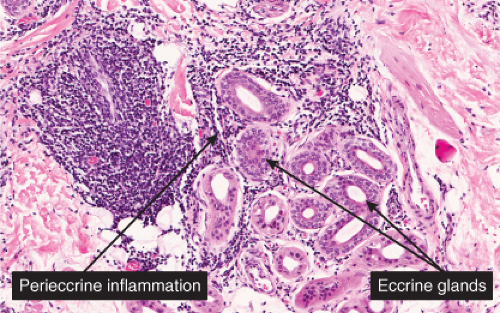

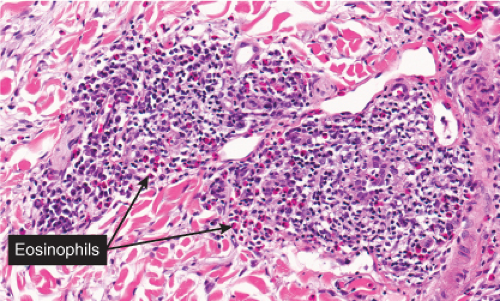

An intense superficial and deep angiocentric, neurotropic, and eccrinotropic infiltrate predominated by lymphocytes with a variable admixture of plasma cells and eosinophils is the principal histopathology. Plasma cells have been identified most frequently in the peripheries of lesions of erythema chronicum migrans, whereas eosinophils are identified in the centers of the lesions. Not infrequently, these florid dermal alterations are accompanied by eczematous epithelial alterations, and interstitial infiltration of the reticular dermis with a concomitant incipient sclerosing reaction. A Warthin-Starry stain may be positive, especially if taken from the advancing border of the lesion.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

secondary syphilis

erythema chronicum migrans

arthropod bite reaction

VB Vasculitis and Vasculopathies

True vasculitis is defined by eosinophilic degeneration of the vessel wall (“fibrinoid necrosis”), infiltration of the vessel wall by neutrophils, with neutrophils, nuclear dust and extravasated red cells in the vessel walls and adjacent dermis. Some of the conditions mentioned here lack these prototypic findings, and may be termed “vasculopathies” (e.g., Degos disease).

Vascular Damage, Scant Inflammatory Cells

Vasculitis, Lymphocytes Predominant

Vasculitis, Neutrophils Prominent

Vasculitis, Mixed Cell Types and/or Granulomas

Thrombotic and Other Microangiopathies

VB1 Vascular Damage, Scant Inflammatory Cells

Although there is significant vascular damage, there is little early inflammatory response. Degos’ syndrome is an example (12).

Degos’ Syndrome

Clinical Summary

The clinical manifestations include crops of asymptomatic, slightly raised, yellowish red papules that gradually develop an atrophic porcelain-white center. These papules tend to affect the trunk and proximal extremities. Degos initially described a cutaneointestinal syndrome, in which distinct skin findings (“drops of porcelain”) were associated with recurrent attacks of abdominal pain that often ended in death from intestinal perforations. He chose the name malignant atrophic papulosis (MAP) to emphasize the serious clinical course of the disease. It is nowadays believed that MAP is a clinicopathologic reaction pattern that can be associated with a number of conditions that are not always lethal. Lesions similar if not identical to MAP have been noted, in particular, in connective tissue diseases such as lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, and progressive systemic sclerosis, in atrophie blanche, and in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. On dermoscopy, a telangiectatic rim can be seen at the periphery of lesions, which can help differentiate this entity from other skin disorders (13).

Histopathology

Although the pathogenesis of Degos’ syndrome is poorly understood, a thrombotic vasculopathy is a characteristic associated finding. A typical lesion shows a wedge-shaped area of altered dermis covered by atrophic epidermis with slight hyperkeratosis. Dermal alterations may include frank necrosis, but more common are edema, extensive mucin deposition, and slight sclerosis. There may be a sparse perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate but the vessel walls are not inflamed. Typically, vascular damage is noted in the vessels at the base of the “cone of necrobiosis.” This damage may be limited to endothelial swelling, but more characteristically, intravascular fibrin thrombi may be noted, suggesting that the dermal and epidermal changes result from ischemia.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

Degos’ syndrome (malignant atrophic papulosis)

atrophie blanche

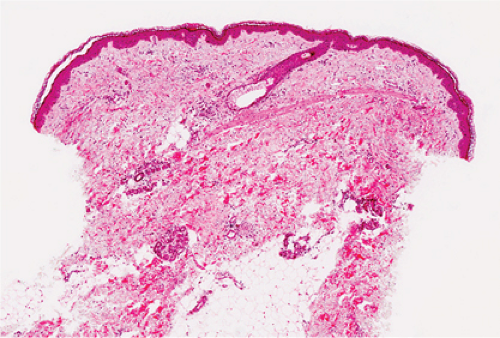

Fig. VB1.a. Degos lesion, low power. Atrophic epidermis overlies a wedge-shaped area of altered dermis (R. Barnhill & K. Busam). |

Fig. VB1.b. Degos lesion, medium power. Within the wedge, there is interstitial degeneration of collagen, and interstitial mucin deposition (R. Barnhill & K. Busam). |

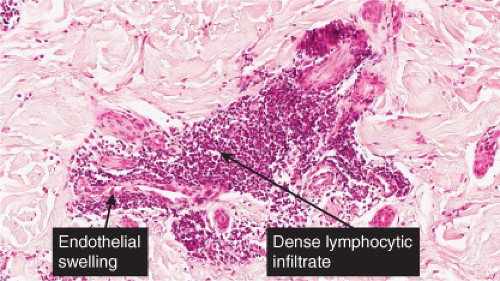

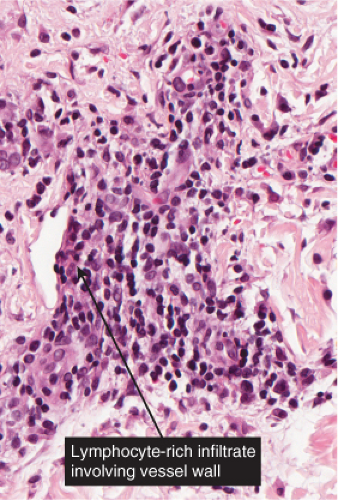

VB2 Vasculitis, Lymphocytes Predominant

The term “lymphocytic vasculitis” is controversial, but there are some conditions in which perivascular and intramural lymphocytes may be associated with some degree of vessel wall damage, not usually including frank fibrinoid necrosis. Most of these conditions are discussed elsewhere as “perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates.” In angiocentric lymphomas, the cells infiltrating the vessel walls are neoplastic, but the process may be mistaken for an inflammatory reaction. Pernio is a prototypic inflammatory example (14).

Pernio

Clinical Summary

Pernio or chilblain usually consists of tender or painful, raised, violaceous plaques on the fingers or toes. Occasionally it is found at a more proximal portion of an extremity in a deeper location in the skin or subcutis. Pernio is caused in susceptible individuals by prolonged exposure to cold above the freezing point, especially in damp climates. It is important to distinguish idiopathic chilblains from chilblains in lupus erythematosus or chilblains associated with other autoimmune disease.

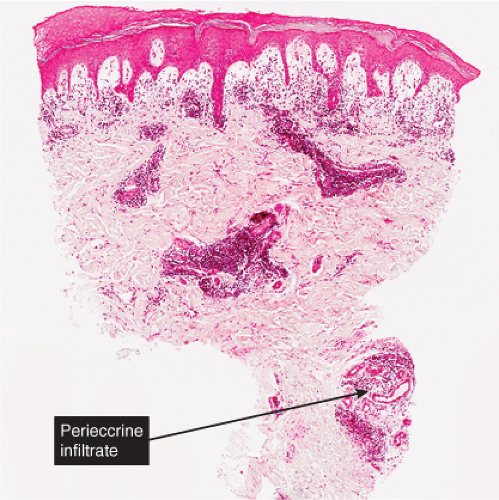

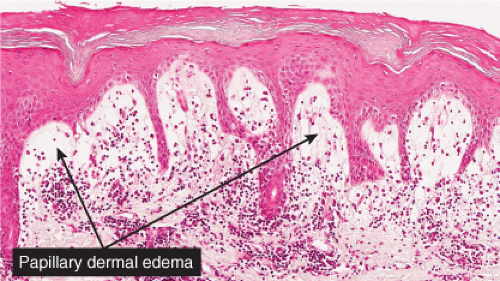

Histopathology

In pernio, intense edema of the papillary dermis is observed. A marked perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate is seen in the upper dermis but sparing the edematous papillary dermis. The blood vessels are said to show a diffuse “fluffy” edema of their walls. The mononuclear infiltrate of the vascular walls is consistent with a lymphocytic vasculitis. The perivascular infiltrate can extend throughout the dermis into the subcutaneous fat. When comparing histology between idiopathic pernio and chilblains associated with autoimmune disease, it has been suggested that perieccrine distribution of lymphocytes is seen more with idiopathic pernio (15).

Pityriasis Lichenoides

Pityriasis lichenoides is an uncommon cutaneous eruption usually classified in two forms that differ in severity. Simultaneous appearance of the two types and transitions between them often occur, suggesting that they are variants of the same disease. Both present as usually non pruritic and painful self-healing lesions occurring in crops and affecting mainly young adults and occasionally children.

The milder form, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, is characterized by recurrent crops of brown-red papules, 4 to 10 mm in size, mainly on the trunk and extremities, that are covered with a scale and generally involute within three to six weeks with postinflammatory pigmentary changes. The more severe form, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA), also referred to as Mucha-Habermann disease, consists of a fairly extensive eruption,

present mainly on the trunk and proximal extremities, and characterized by erythematous papules that develop into papulonecrotic, occasionally hemorrhagic or vesiculopustular lesions that resolve within a few weeks, usually with little or no scarring. Although the individual lesions follow an acute course, the disorder is chronic, extending over several months or even years with development of new lesions and variable periods of remission.

present mainly on the trunk and proximal extremities, and characterized by erythematous papules that develop into papulonecrotic, occasionally hemorrhagic or vesiculopustular lesions that resolve within a few weeks, usually with little or no scarring. Although the individual lesions follow an acute course, the disorder is chronic, extending over several months or even years with development of new lesions and variable periods of remission.

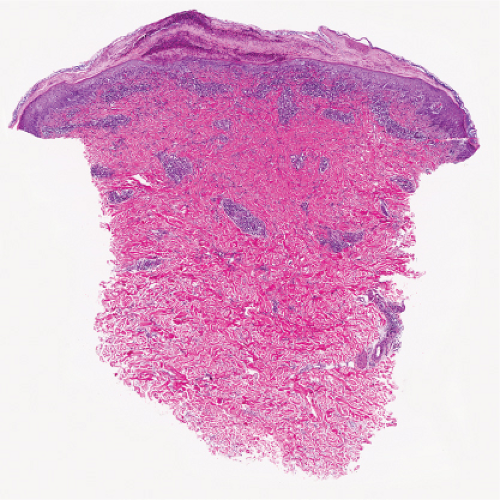

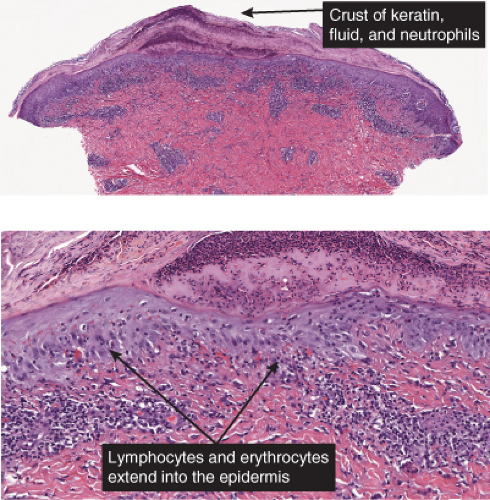

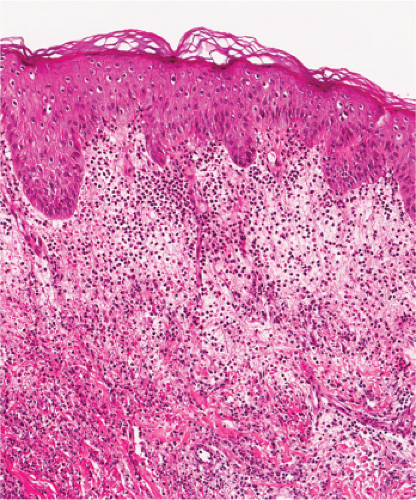

Histopathology

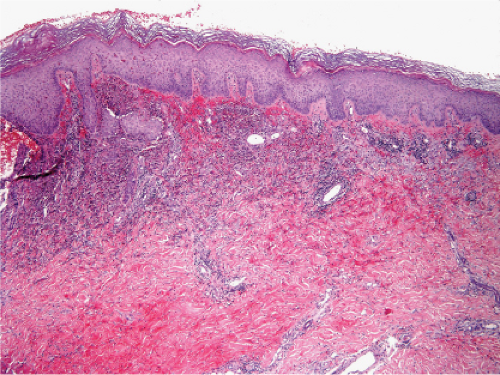

In pityriasis lichenoides chronica, there is a superficial perivascular and lichenoid infiltrate composed of lymphocytes that extend into the epidermis, where there is vacuolar alteration of the basal layer, mild spongiosis, a few necrotic keratinocytes, and confluent parakeratosis. Melanophages and small numbers of extravasated erythrocytes are commonly seen in the papillary dermis. In PLEVA, there is a perivascular and dense band

like predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis that extends into the reticular dermis in a wedge-shaped pattern. The infiltrate obscures the dermal-epidermal junction with pronounced vacuolar alteration of the basal layer, marked exocytosis of lymphocytes and erythrocytes, and intercellular and intracellular edema leading to variable degree of epidermal necrosis. Ultimately, erosion or ulceration may occur. The overlying cornified layer shows parakeratosis and a scaly crust with neutrophils in the more severe cases. Variable degrees of papillary dermal edema, endothelial swelling, and extravasated erythrocytes are seen. Severe vascular damage is rarely found except in a severe febrile ulceronecrotic variant of PLEVA where lymphocytic vasculitis with leukocytoclasis may be seen.

like predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis that extends into the reticular dermis in a wedge-shaped pattern. The infiltrate obscures the dermal-epidermal junction with pronounced vacuolar alteration of the basal layer, marked exocytosis of lymphocytes and erythrocytes, and intercellular and intracellular edema leading to variable degree of epidermal necrosis. Ultimately, erosion or ulceration may occur. The overlying cornified layer shows parakeratosis and a scaly crust with neutrophils in the more severe cases. Variable degrees of papillary dermal edema, endothelial swelling, and extravasated erythrocytes are seen. Severe vascular damage is rarely found except in a severe febrile ulceronecrotic variant of PLEVA where lymphocytic vasculitis with leukocytoclasis may be seen.

Fig. VB2.a. Pernio, low power. There is edema of the papillary dermis, with a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial infiltrate. |

Fig. VB2.b. Pernio, medium power. The infiltrate tends to be localized about and within the walls of vessels of the superficial plexus. Papillary dermal edema may be mild or pronounced, as seen here. |

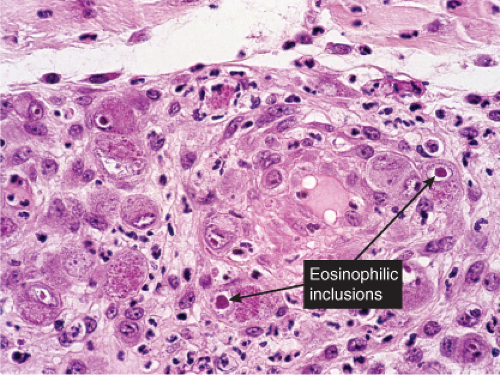

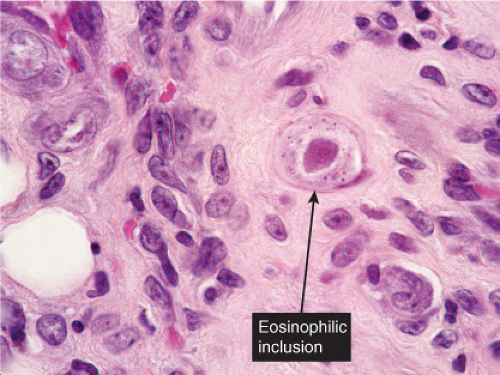

Cytomegalovirus Infection

See Figs. VB2.h–j.

Fig. VB2.i. Cytomegalovirus, medium power. Endothelial cells are markedly swollen, and some contain inclusions (intranuclear and/or cytoplasmic). |

Fig. VB2.j. Cytomegalovirus, high power. A fibroblast contains a characteristic large eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion body. |

Fig. VB2.k. Erythema chronicum migrans, low power. A tight perivascular cuff of lymphocytes about the superficial and mid dermal vessels. |

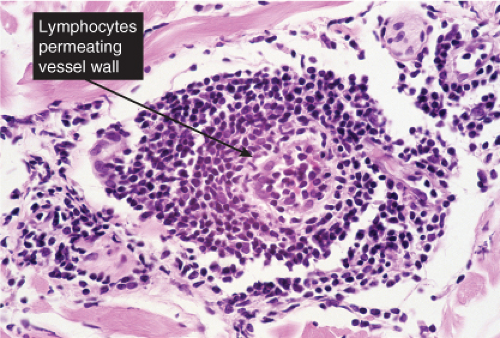

Fig. VB2.l. Erythema chronicum migrans, high power. In this example, the lymphocytes diffusely infiltrate the vessel wall. However, there is no vessel wall necrosis (see VB3). |

Erythema Chronicum Migrans

See Figs. VB2.k,l.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

lymphocytic vasculitis

lupus erythematosus

lymphomatoid papulosis

pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA)

pityriasis lichenoides chronica

purpura pigmentosa chronica

morbilliform viral infections

Lyme disease

perniosis (chilblains)

angiocentric mycosis fungoides

angiocentric T-cell lymphoma/lymphomatoid granulomatosis

cytomegalovirus inclusion disease

Behcet’s syndrome

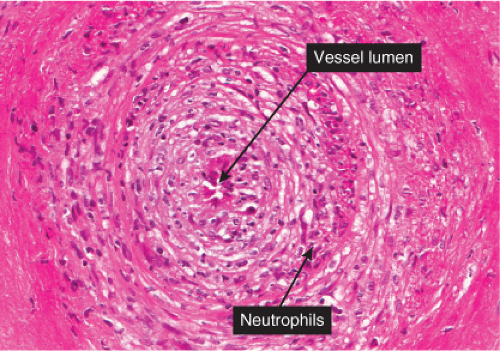

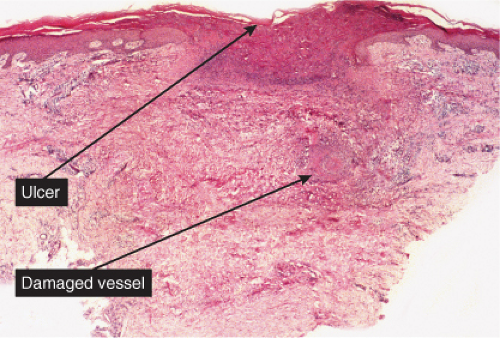

VB3 Vasculitis, Neutrophils Prominent

Neutrophils are prominent in the infiltrate, with fibrinoid necrosis and nuclear dust; eosinophils and lymphocytes are also found. Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is prototypic (16).

Polyarteritis Nodosa and Microscopic Polyangiitis

Clinical Summary

Classic polyarteritis nodosa is a systemic vasculitic disorder in which large arteries are involved and in which ischemic glomerular lesions are

common but glomerulonephritis is rare. Microscopic polyarteritis nodosa, also termed microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) refers to a systemic small-vessel vasculitis primarily affecting arterioles and capillaries that is typically associated with focal necrotizing glomerulonephritis with crescents. The majority of patients with MPA are anti-MPO (p-ANCA) -positive. Some cases of vasculitis present with an overlapping syndrome affecting both small and medium-sized arteries.

common but glomerulonephritis is rare. Microscopic polyarteritis nodosa, also termed microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) refers to a systemic small-vessel vasculitis primarily affecting arterioles and capillaries that is typically associated with focal necrotizing glomerulonephritis with crescents. The majority of patients with MPA are anti-MPO (p-ANCA) -positive. Some cases of vasculitis present with an overlapping syndrome affecting both small and medium-sized arteries.

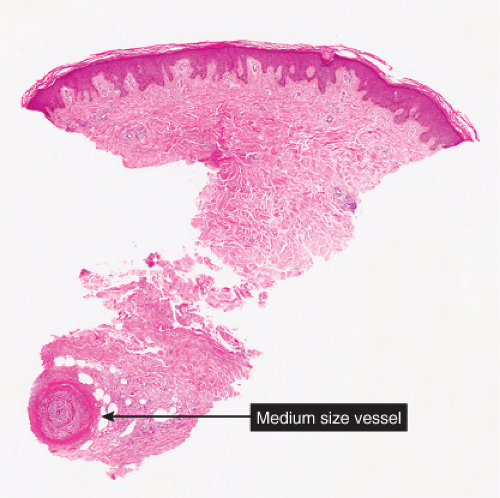

Fig. VB3.a. Polyarteritis nodosa, low power. Vessels in the deep dermis and subcutis are thick-walled, and there is a diffuse subcutaneous infiltrate. |

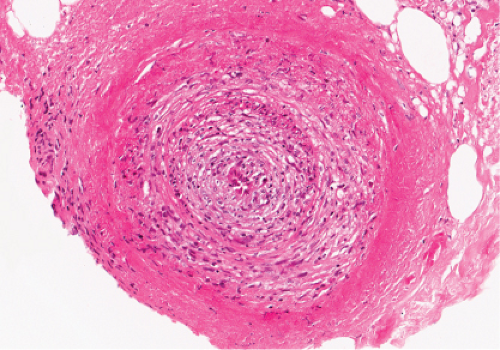

Fig. VB3.b. Polyarteritis nodosa, high power. The involved vessel is usually in the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat. |

Fig. VB3.c. Polyarteritis nodosa, high power. There are areas of eosinophilic change (“fibrinoid necrosis”), with neutrophilic infiltration, in the walls of large vessels (small muscular arteries). |

The majority of patients with MPA are male and over 50 years of age. Prodromal symptoms include fever, myalgias, arthralgias, and sore throat. The most common clinical feature is renal disease manifesting as microhematuria, proteinuria, or acute oliguric renal failure. Although in classic PAN, cutaneous involvement is rare, 30% to 40% of patients with MPA exhibit skin changes. With cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, the initial signs include livido reticularis, tender subcutaneous nodules, and ulcerations. Purpura, petechiae, and necrosis can be seen. The legs are most commonly affected (17) With MPA, the most common clinical sign is palpable purpura on the legs. MPA can also present with ulcers, cutaneous necrosis, splinter hemorrhages, and vesicles (18).

Histopathology

The characteristic lesion of classic PAN is a panarteritis involving medium-sized and small arteries. Even though in classic PAN, the arteries show the characteristic changes in many visceral sites, affected skin often shows only small-vessel disease, and arterial involvement is typically focal. The changes affecting cutaneous small vessels are usually those of a necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). If there is a clinical presentation of cutaneous nodules, panarteritis similar to visceral lesions is usually detected. In classic PAN, the lesions typically are in different stages of development (i.e., fresh and old). Early lesions show degeneration of the arterial wall with deposition of fibrinoid material, and partial to complete destruction of the external and internal elastic laminae. An infiltrate present within and around the arterial wall is composed largely of neutrophils showing evidence of leukocytoclasia, although it often contains eosinophils. At a later stage, intimal proliferation and thrombosis lead to complete occlusion of the lumen with subsequent ischemia and possibly ulceration. The infiltrate also may contain lymphocytes, histiocytes, and some plasma cells. In the healing stage, there is fibroblastic proliferation extending into the perivascular area. The small vessels of the middle and upper dermis often exhibit a nonspecific lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate.

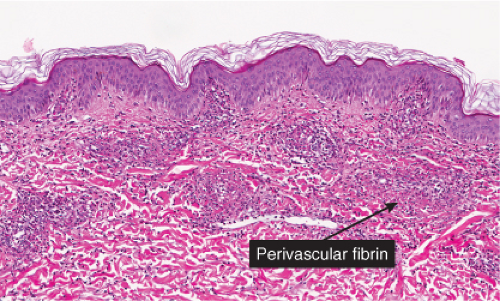

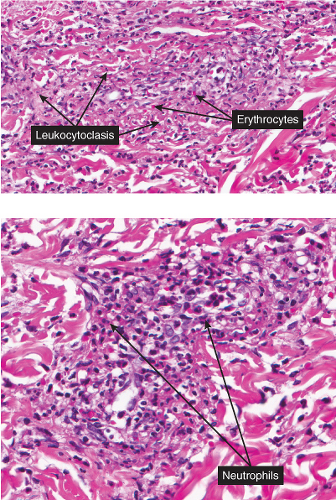

Neutrophilic Small-Vessel Vasculitis (Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis)

Clinical Summary

Many different disease processes can be accompanied by small-vessel vasculitis with predominantly neutrophilic infiltrates. The clinical and histologic manifestations are thus fairly nonspecific. The majority of cases are idiopathic but associated diseases to be considered range from conditions limited to the skin such as most cases of drug-induced vasculitis to systemic conditions such as infections including hepatitis C, malignancies, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, connective tissue diseases, or ANCA-associated disorders such as Churg–Strauss syndrome, microscopic polyangiitis, or Wegener’s granulomatosis (19).

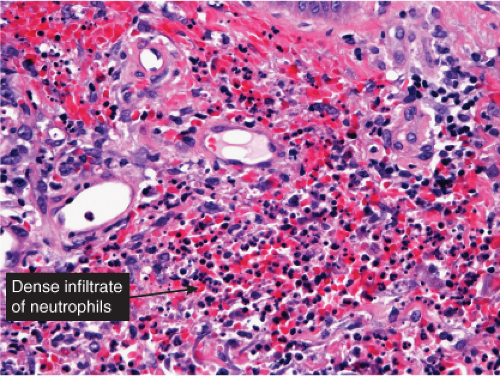

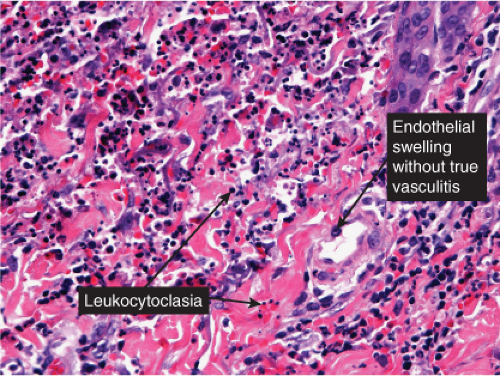

Histopathology

Neutrophilic small-vessel vasculitis is a reaction pattern of small dermal vessels, almost exclusively postcapillary venules, characterized by a combination of vascular damage and an infiltrate composed largely of neutrophils. Because there is often fragmentation of nuclei (karyorrhexis or leukocytoclasis), the term leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is frequently used. Depending on its severity, this process may be subtle and limited to the superficial dermis or be pandermal and florid and associated with necrosis and ulceration. If edema is prominent, a subepidermal blister may form. If the neutrophilic infiltrate is dense and there is pustule formation, the term pustular vasculitis may be applied. In a typical case of LCV, the dermal vessels show swelling of the endothelial cells and deposits of strongly eosinophilic strands of fibrin within and around their walls. The deposits of fibrin and the marked edema together give the vessel walls a “smudgy” appearance referred to as fibrinoid degeneration. The cellular infiltrate is present predominantly around the dermal blood vessels or within the vascular walls, so that the outline of the blood vessels may appear indistinct. The infiltrate consists mainly of neutrophils and of varying numbers of eosinophils and mononuclear cells. The infiltrate also is scattered throughout the upper dermis in association with fibrin deposits between and within collagen bundles. Extravasation of erythrocytes is commonly present. The appearance of the reaction pattern depends on the stage at which the biopsy is taken. In older lesions, the number of neutrophils may be decreased and the number of mononuclear cells increased so that mononuclear cells may predominate and a designation of a lymphocytic or even granulomatous vasculitis or vascular reaction might be made.

Erythema Elevatum Diutinum

See Clin. Fig. VB3.b.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis

neutrophilic dermatoses

Sweet’s syndrome

granuloma faciale

bowel-associated dermatosis–arthrosis syndrome

septic/embolic lesions of gonococcemia/meningococcemia

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Rickettsia rickettsii)

polyarteritis nodosa

Fig. VB3.e. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, medium power. The neutrophil-rich infiltrate is angiocentric with a less intense interstitial component.

Fig. VB3.f,g. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, high power. There is fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, with neutrophilic infiltration and leukocytoclasia around the involved vessels.

erythema elevatum diutinum

Behcet’s syndrome

papulonecrotic tuberculid

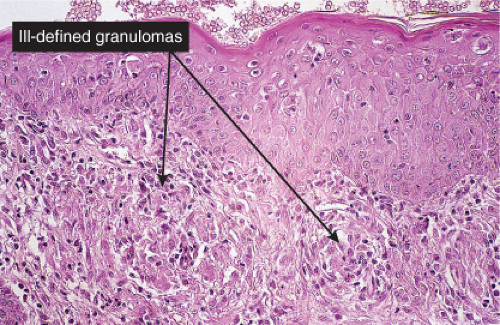

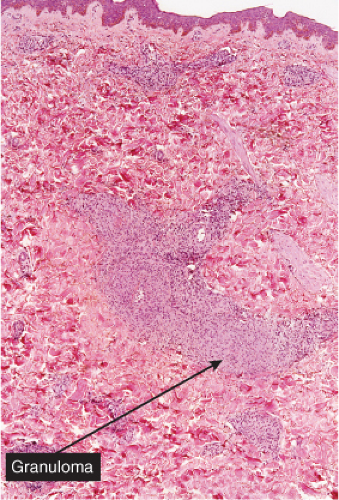

VB4 Vasculitis, Mixed Cell Types and/or Granulomas

Histiocytes and giant cells are a part of the infiltrate. Lymphocytes and eosinophils can also be found depending on the diagnosis. Giant cell arteritis is a true inflammation of the artery wall (true arteritis), although there is no fibrinoid necrosis. Most cases of giant cell arteritis involve vessels of the subcutis. Allergic granulomatosis (Churg–Strauss) is prototypic (20).

Churg–Strauss Syndrome (Allergic Granulomatosis)

Clinical Summary

Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS) is a systemic disease occurring in asthmatic patients

characterized by vasculitis, eosinophilic infiltration of multiple organs, and peripheral eosinophilia. There is considerable overlap of this disease process with other systemic vasculitides, and with other inflammatory disorders exhibiting eosinophils, such as eosinophilic pneumonitis. The internal organs most commonly involved are the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract, and, less commonly, the peripheral nerves and the heart. In contrast to PAN, renal failure is rare. A slightly broader definition of CSS has been proposed requiring asthma, blood hypereosinophilia, and systemic vasculitis involving two or more extrapulmonary organs.

characterized by vasculitis, eosinophilic infiltration of multiple organs, and peripheral eosinophilia. There is considerable overlap of this disease process with other systemic vasculitides, and with other inflammatory disorders exhibiting eosinophils, such as eosinophilic pneumonitis. The internal organs most commonly involved are the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract, and, less commonly, the peripheral nerves and the heart. In contrast to PAN, renal failure is rare. A slightly broader definition of CSS has been proposed requiring asthma, blood hypereosinophilia, and systemic vasculitis involving two or more extrapulmonary organs.

Clin. Fig. VB4. Granulomatous vasculitis. This inflammatory nodule histologically showed evidence of a granulomatous vasculitis. |

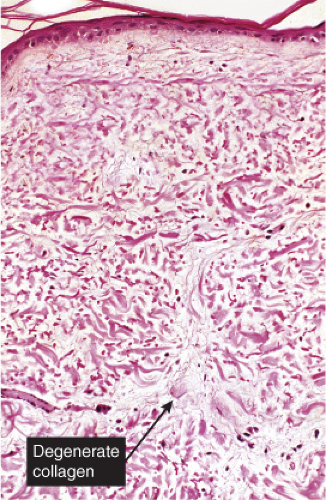

Fig. VB4.a. Granulomatous vasculitis, low power. There is a perivascular granulomatous infiltrate of histiocytes and lymphocytes in the reticular dermis. (R. Barnhill & K. Busam). |

Two types of cutaneous lesions may occur: (1) hemorrhagic lesions similar to Henoch–Schönlein purpura varying from petechiae to extensive ecchymoses, often with areas of erythema and sometimes with necrotic ulcers, and (2) cutaneous–subcutaneous nodules. The extremities are the most common sites of skin lesions, but the trunk may also be involved and some cases are generalized. ANCA tests obtained during an active phase of the disease contain p-ANCA in the majority of cases. There is also a limited form, in which the lesions are confined to the conjunctiva, the skin, and the subcutaneous tissue.

Histopathology

The areas of cutaneous hemorrhage typically show changes of LCV. Eosinophils may be conspicuous. In some instances, the dermis shows a granulomatous reaction composed predominantly of radially arranged histiocytes and, frequently, multinucleated giant cells centered around degenerated collagen fibers. The central portions of the granulomas contain not only degenerated collagen fibers but also dense aggregates of disintegrated cells, particularly eosinophils. These granulomas have been referred to as Churg–Strauss granulomas. However, they are not always present and similar findings can also be observed in other disease processes, such as connective tissue diseases (rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus), Wegener’s granulomatosis, PAN, lymphoproliferative disorders, subacute bacterial endocarditis, chronic active hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease. The granulomas in the subcutaneous tissue may attain considerable size through expansion and confluence, thus giving rise to the clinically apparent cutaneous–subcutaneous nodules. They are embedded in a diffuse inflammatory exudate rich in eosinophils. Similar changes have also been observed in other diseases, such as PAN.

Papulonecrotic Tuberculid

See Figs. VB4.c, d.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

allergic granulomatosis (Churg–Strauss)

Wegener’s granulomatosis

giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis)

erythema chronicum migrans

erythema nodosum leprosum

some insect bite reactions

“secondary vasculitis” at the base of ulcers of diverse etiology

Behcet’s syndrome

palisaded and neutrophilic granulomatosis

interstitial granulomatous dermatitis

Fig. VB4.c. Papulonecrotic tuberculid, low power. Wedge-shaped infarction of the dermis and epidermis, caused by vasculitis (S. Lucas). |

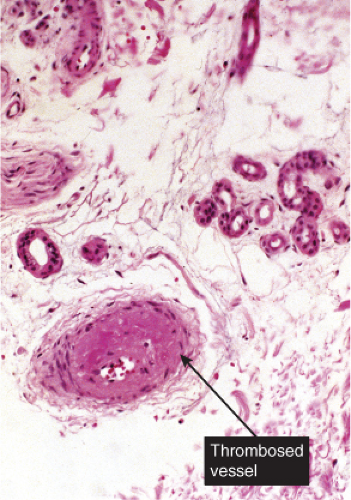

VB5 Thrombotic and Other Microangiopathies

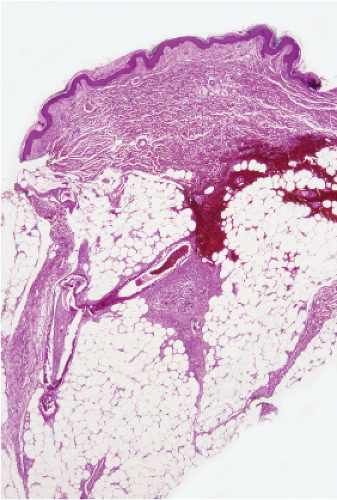

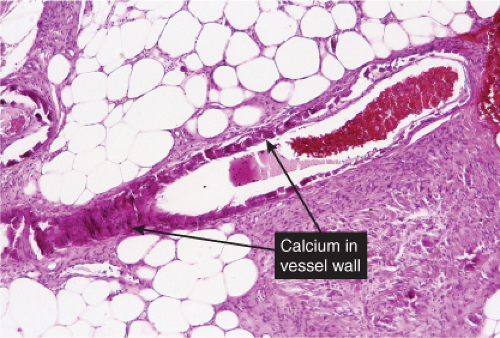

The dermal vessels contain fibrin, red cells and platelet thrombi, and/or eosinophilic protein precipitates. Coagulopathies of diverse etiologies may have similar histologic features (see section IIIG). Calciphylaxis is a microangiopathy that appears to be caused by calcification of the media of small arteries, followed by fibroplasia affecting the intima and occluding the lumen (12).

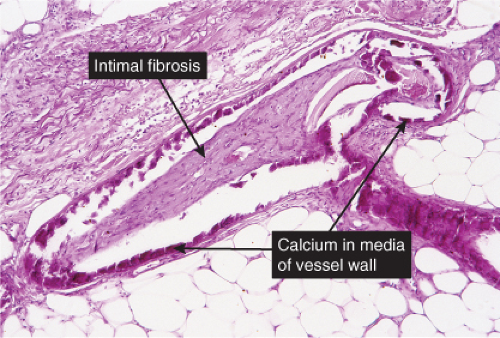

Fig. VB5.a. Calciphylaxis, low power. Associated with fat necrosis and hemorrhage, there is a vessel in the subcutis with a calcified and thickened wall. |

Fig. VB5.b. Calciphylaxis, medium power. There is necrosis of fat adjacent to the abnormal vessel. Necrosis is often much more extensive than in this example, and often involves the dermis. |

Calciphylaxis

Clinical Summary

Calciphylaxis is a life-threatening condition in which there is progressive calcification of small and medium-sized vessels of the subcutis with thickening of the intima by fibrosis and subsequent vascular compromise resulting in ischemia and necrosis. It most frequently arises in the setting of hyperparathyroidism associated with chronic renal failure, and is often, but not always, associated with an elevated serum calcium/phosphate product. Clinically, the lesions present as a panniculitis or vasculitis. Bullae, ulcerations, or a livedo reticularis-like eruption can be present. Lesions usually occur over areas with high fat content such as the abdomen, thighs, calves, and buttocks. The digits, breasts, tongue, and penis can also be affected. Early lesions appear as subcutaneous nodules or violaceous plaques. Later lesions with black central necrosis are seen. A biopsy from the center of an eschar will usually show characteristic changes (22).

Histopathology

The histologic changes in calciphylaxis include calcium deposits in the subcutis, chiefly within the walls of small and medium-sized arteries. These deposits can be associated with endovascular fibrosis, thrombosis, or global calcific obliteration. Calcification can also be identified within the soft tissues. The vascular lesions result in ischemic and/or gangrenous necrosis of the subcutaneous fat and overlying skin.

Livedo Reticularis

See Clin. Fig. VB5.b.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

septicemia

disseminated intravascular coagulation

thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

purpura fulminans

coumarin necrosis

lupus anticoagulant

amyloidosis

porphyria cutanea tarda and other porphyrias

calciphylaxis

thrombophlebitis and superficial migratory thrombophlebitis

Lucio reaction

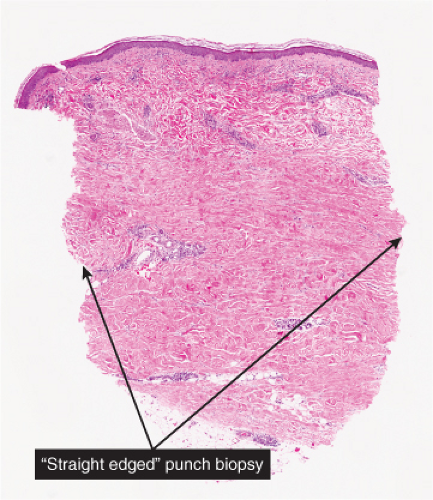

VC Diffuse Infiltrates of the Reticular Dermis

Diffuse infiltrates of the reticular dermis may show some relation to vessels or to skin appendages, or may be randomly distributed in the reticular dermis.

Diffuse Infiltrates, Lymphocytes Predominant

Diffuse Infiltrates, Neutrophils Predominant

Diffuse Infiltrates, “Histiocytoid” Cells Predominant

Diffuse Infiltrates, Plasma Cells Prominent

Diffuse Infiltrates, Mast Cells Predominant

Diffuse Infiltrates, Eosinophils Predominant

Diffuse Infiltrates, Mixed Cell Types

Diffuse Infiltrates, Pigment Cells

Diffuse Infiltrates, Extensive Necrosis

VC1 Diffuse Infiltrates, Lymphocytes Predominant

Lymphocytes are seen almost to the exclusion of other cell types. Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltration is prototypic (23).

Jessner’s Lymphocytic Infiltration of the Skin

Clinical Summary

This poorly understood entity is characterized by asymptomatic papules or well-demarcated, slightly infiltrated red plaques, which may develop central clearing. In contrast to the lesions of chronic lupus erythematosus, the surface shows no follicular plugging or atrophy. The eruption may be precipitated or aggravated by sunlight. Lesions arise most often on the face, but may also involve the neck and upper trunk. Affected patients are usually middle-aged men and women. Variable

numbers of lesions (one to many) often persist for several months or several years. They may disappear without sequelae, or recur at previously involved sites or elsewhere. As a historical note, this lesion was one of Lever’s “Five L’s,” which may be slightly modified as: Lymphoma and Leukemia cutis, Lymphocytoma cutis, Jessner’s Lymphocytic infiltrate, Lupus erythematosus, polymorphous Light eruption, and Lepidoptera’the latter intended to signify assault by arthropods of various kinds.

numbers of lesions (one to many) often persist for several months or several years. They may disappear without sequelae, or recur at previously involved sites or elsewhere. As a historical note, this lesion was one of Lever’s “Five L’s,” which may be slightly modified as: Lymphoma and Leukemia cutis, Lymphocytoma cutis, Jessner’s Lymphocytic infiltrate, Lupus erythematosus, polymorphous Light eruption, and Lepidoptera’the latter intended to signify assault by arthropods of various kinds.

Clin. Fig. VC1.a. Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate. Typical infiltrated red plaques with central clearing are seen on the forehead. |

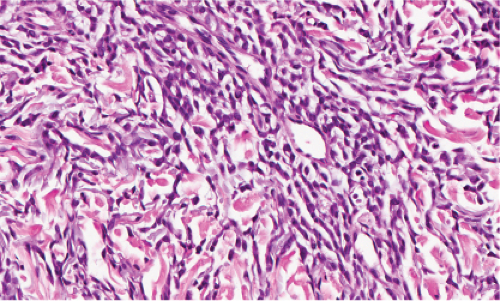

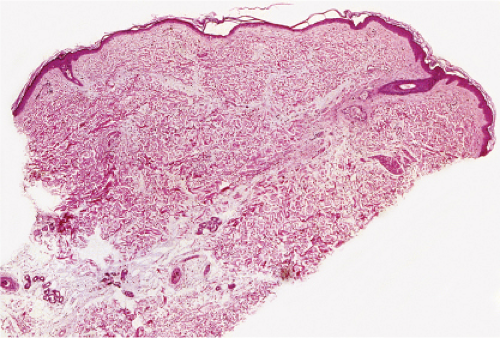

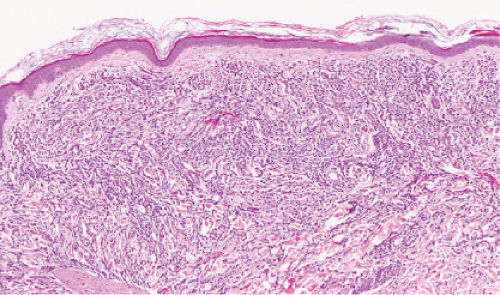

Fig. VC1.a. Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltration, low power. A dense perivascular and interstitial infiltrate extends through the full thickness of the dermis. |

Fig. VC1.b. Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltration, medium power. The infiltrate is partly perivascular but mainly diffuse. |

Histopathology

The epidermis may be normal but often appears slightly flattened. In the dermis, there are

moderately dense perivascular and diffuse infiltrates composed of small, mature lymphocytes admixed with occasional histiocytes and plasma cells. The infiltrate may extend around folliculo-sebaceous units and into subcutaneous adipose tissue.

moderately dense perivascular and diffuse infiltrates composed of small, mature lymphocytes admixed with occasional histiocytes and plasma cells. The infiltrate may extend around folliculo-sebaceous units and into subcutaneous adipose tissue.

Clin. Fig. VC1.b. Leukemia cutis. An elderly male with chronic lymphocytic leukemia developed recurrent ulcerated nodules on an infiltrated violaceous plaque. Local radiation therapy was successful. |

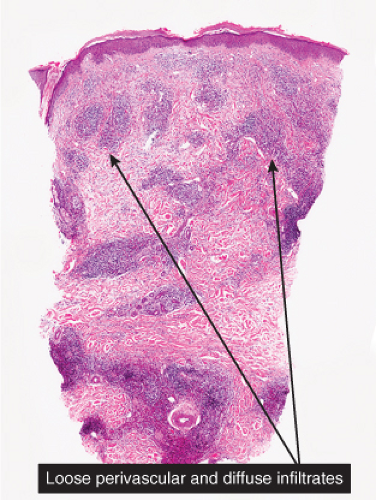

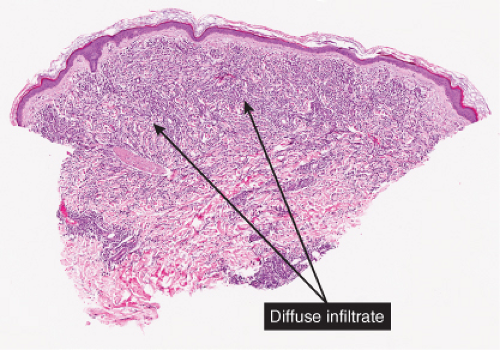

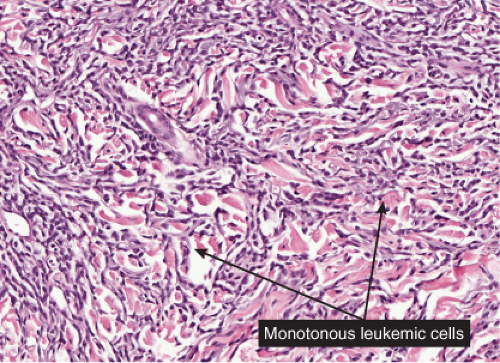

Fig. VC1.d. Leukemia cutis, low power. In this example of acute myelogenous leukemia, there is a dense diffuse infiltrate in the reticular dermis. |

Fig. VC1.e. Leukemia cutis, medium power. The infiltrate shows little tendency to perivascular or periadnexal orientation. There is no epidermal involvement. |

Fig. VC1.f. Leukemia cutis, high power. The lesional cells tend to dissect between collagen bundles. |

Leukemia Cutis

See Clin. Fig. VC1.b and Figs. d–g.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia/lymphocytoma cutis

Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate

leukemia cutis (lymphocytic lymphoma, CLL)

VC2 Diffuse Infiltrates, Neutrophils Predominant

Neutrophils are the main infiltrating cells although lymphocytes can be found. Sweet’s syndrome is prototypic (24). Erysipelas is another good example (25).

Acute Febrile Neutrophilic Dermatosis (Sweet’s Syndrome)

Clinical Summary

Classic Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by acute onset of fever, leukocytosis, and erythematous plaques, vesicles or pustules infiltrated by neutrophils. This condition typically occurs in middle-aged women after nonspecific infections of the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract. In addition to the classic Sweet’s syndrome, sterile lesions with neutrophilic infiltrates that improve on steroid treatment can be found in a variety of other clinical conditions. Such infiltrates can be associated with inflammatory diseases such as autoimmune disorders or with recovery from infection. They may also develop in patients with hemoproliferative disorders or solid tumors, as well as in pregnant women.

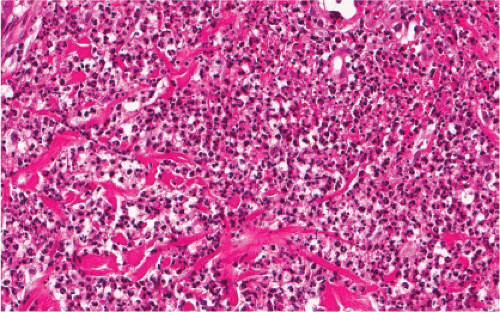

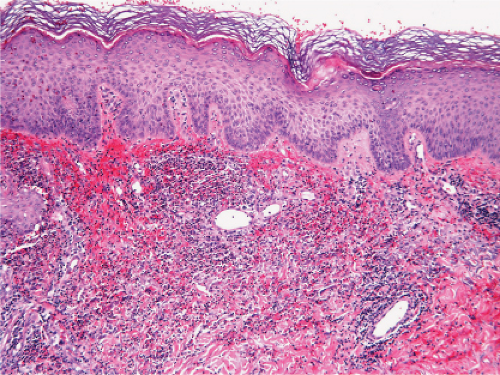

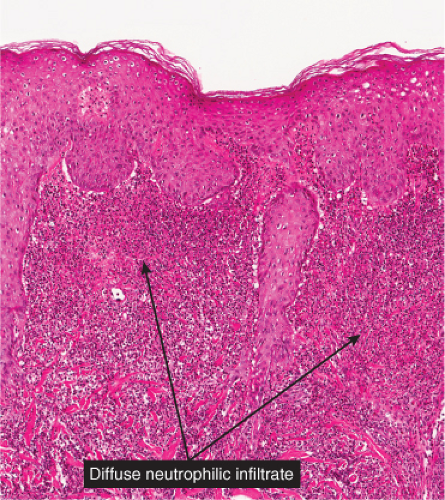

Histopathology

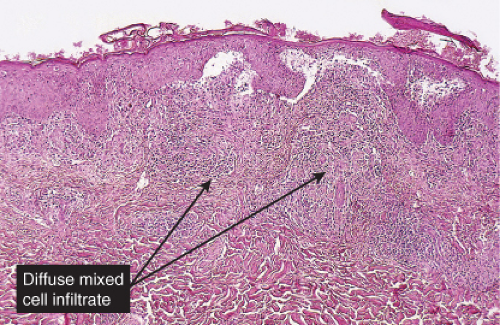

There is a dense perivascular infiltrate composed largely of neutrophils, often with leukocytoclasia. In addition, there are mononuclear cells, such as lymphocytes and histiocytes, and occasional eosinophils. The inflammatory cells typically assume a bandlike

distribution throughout the papillary dermis. The density of the infiltrate varies and may be limited in a small proportion of cases. There is usually vasodilation and swelling of endothelium with moderate erythrocyte extravasation. The prominent edema of the upper dermis in some instances may result in subepidermal blister formation. Extensive vascular damage is not a feature of Sweet’s syndrome. The histologic appearance varies depending on the stage of the process. In later stages, lymphocytes and histiocytes may predominate. It is important to realize that the composition and distribution of the infiltrate are not specific enough to histologically rule out an infectious process.

distribution throughout the papillary dermis. The density of the infiltrate varies and may be limited in a small proportion of cases. There is usually vasodilation and swelling of endothelium with moderate erythrocyte extravasation. The prominent edema of the upper dermis in some instances may result in subepidermal blister formation. Extensive vascular damage is not a feature of Sweet’s syndrome. The histologic appearance varies depending on the stage of the process. In later stages, lymphocytes and histiocytes may predominate. It is important to realize that the composition and distribution of the infiltrate are not specific enough to histologically rule out an infectious process.

Clin. Fig. VC2. Sweet’s syndrome. A middle-aged man experienced the acute onset of fever and erythematous plaques on the face (Photo by William K. Witmer). |

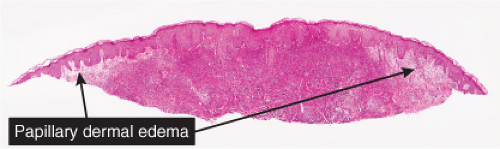

Fig. VC2.a. Sweet’s syndrome, low power. There is edema of the upper dermis, and a diffuse cellular infiltrate in the reticular dermis. |

Fig. VC2.c. Sweet’s syndrome, medium power. The infiltrate is composed almost entirely of neutrophils. Diagnostic changes of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are not observed. |

Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Clinical Summary

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands is a recently described entity in the family of neutrophilic dermatoses which also include Sweet’s syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, and rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis (26,27). These patients present with an eruption that is limited to the dorsal aspect of the hands. The lesions begin as tender plaques and nodules with edema and pustules and a violaceous rim. The pustules may become quite large and some lesions may ulcerate. There is preferential involvement for the radial aspect of the hand. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands most commonly occurs in women (76%) and in adults (mean age of 62 years). There may be an accompanying fever. Unlike classic Sweet’s syndrome, neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands is generally not associated with an underlying systemic disease or malignancy. However, there have been rare patients with remote history of carcinoma and one with an unclassified type of arthritis.

Histopathology

Biopsies of neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands reveal a dense neutrophilic infiltrate throughout the dermis which is abscess-like. There may be dermal edema and leukocytoclasia. Some cases have shown vasculitis and fibrinoid necrosis of small vascular channels, however, in many cases, the blood vessels are unaltered (28). This histopathology can be indistinguishable from Sweet’s syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum making clinical-pathologic correlation paramount. One must always exclude the possibility of an infectious process by the use of special stains for organisms as well as tissue culture. See images on next page.

Erysipelas

Clinical Summary

Erysipelas is an acute superficial cellulitis of the skin caused by group A streptococci. It is characterized by a well-demarcated, slightly indurated, dusky red area with an advancing, palpable border. In some patients, erysipelas has a tendency to recur periodically in the same areas. In the early antibiotic era, the incidence of erysipelas appeared to be on the decline and most cases occurred on the face. More recently, however, there appears to have been an increase in the incidence, and facial sites are now less common whereas erysipelas of the legs is predominant. Obesity has been found to be an independent risk factor for local complications of erysipelas, including hemorrhage, bullous lesions, abscesses, and necrosis (29).

Fig. VC2.e. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands, low magnification. There is a dense inflammatory infiltrate in the upper and mid reticular dermis. |

Histopathology

The dermis shows marked edema and dilatation of the lymphatics and capillaries. There is a diffuse infiltrate, composed chiefly of neutrophils, that extends throughout the dermis and occasionally into the subcutaneous fat. It is loosely arranged around dilated blood and lymph vessels. If sections are stained with the Giemsa or Gram stain, streptococci may be found in the tissue and within lymphatics. In cases of recurring erysipelas, the lymph vessels of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue show fibrotic thickening of their walls with partial or complete occlusion of the lumen. Erysipelas and cellulitis must be distinguished from Sweet’s-like eruptions and vice versa. This distinction cannot always be made on histologic grounds alone.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

acute neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome)

erythema elevatum diutinum

Fig. VC2.i. Cellulitis, low power. The dermis is edematous and there is a patchy infiltrate in the reticular dermis.

Fig. VC2.k. Cellulitis, high power. Most of the cells in the infiltrate are neutrophils. there is no necrosis, and bacteria are frequently not demonstrable in the dermis.

rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis

infectious abscess from bacteria, mycobacterial, or fungi

neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands

granuloma faciale

cutaneous reaction to cytokines especially G-CSF

bowel arthrosis dermatosis syndrome

(bowel bypass syndrome)

erysipelas

cellulitis

pyoderma gangrenosum

dermis adjacent to folliculitis

abscess

Behcet’s syndrome

halogenoderma

VC3 Diffuse Infiltrates, “Histiocytoid” Cells Predominant

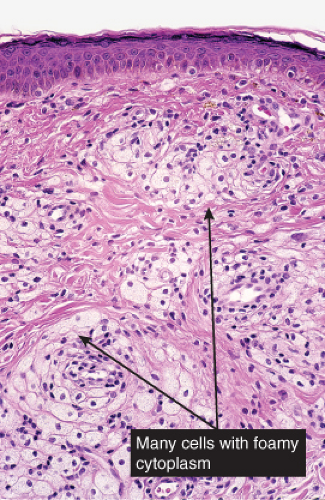

Histiocytes or histiocytoid cells are found in great numbers in the dermal infiltrate. Some may be foamy, others may contain organisms. The leukemic cells of myeloid leukemia may be easily mistaken for histiocytes and may have histiocytic differentiation (myelomonocytic leukemia). Lepromatous leprosy is a good example (30).

Lepromatous Leprosy

Lepromatous leprosy (LL) initially has cutaneous and mucosal lesions, with neural changes occurring later. The lesions usually are numerous and are symmetrically

arranged. There are three clinical types: macular, infiltrative-nodular, and diffuse. In the macular type, numerous ill-defined, confluent, either hypopigmented or erythematous macules are observed. They are frequently slightly infiltrated. The infiltrative-nodular type, the classical and most common variety, may develop from the macular type or arise as such. It is characterized by papules, nodules, and diffuse infiltrates that are often dull red. Involvement of the eyebrows and forehead often results in a leonine facies, with a loss of lateral eyebrows and eyelashes. The lesions themselves are not notably hypoesthetic, although, through involvement of the large peripheral nerves, disturbances of sensation and nerve paralyses develop. The nerves that are most commonly involved are the ulnar, radial, and common peroneal nerves. The diffuse type of leprosy, called Lucio leprosy, most common in Mexico and Central America, shows diffuse infiltration of the skin without nodules. This infiltration may be quite inconspicuous except for the alopecia of the eyebrows and eyelashes it produce. Acral, symmetric anesthesia is generally present. Rarely, lepromatous leprosy can present as a single lesion, rather than as multiple lesions.

arranged. There are three clinical types: macular, infiltrative-nodular, and diffuse. In the macular type, numerous ill-defined, confluent, either hypopigmented or erythematous macules are observed. They are frequently slightly infiltrated. The infiltrative-nodular type, the classical and most common variety, may develop from the macular type or arise as such. It is characterized by papules, nodules, and diffuse infiltrates that are often dull red. Involvement of the eyebrows and forehead often results in a leonine facies, with a loss of lateral eyebrows and eyelashes. The lesions themselves are not notably hypoesthetic, although, through involvement of the large peripheral nerves, disturbances of sensation and nerve paralyses develop. The nerves that are most commonly involved are the ulnar, radial, and common peroneal nerves. The diffuse type of leprosy, called Lucio leprosy, most common in Mexico and Central America, shows diffuse infiltration of the skin without nodules. This infiltration may be quite inconspicuous except for the alopecia of the eyebrows and eyelashes it produce. Acral, symmetric anesthesia is generally present. Rarely, lepromatous leprosy can present as a single lesion, rather than as multiple lesions.

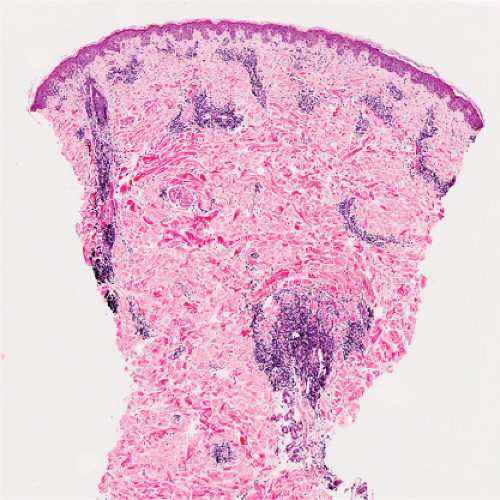

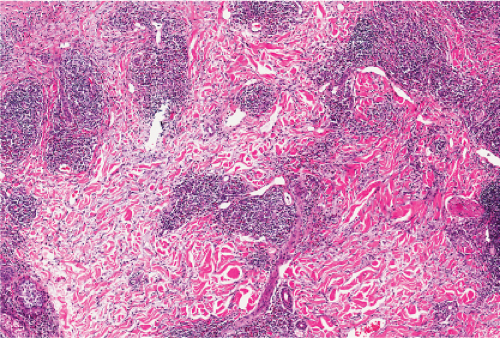

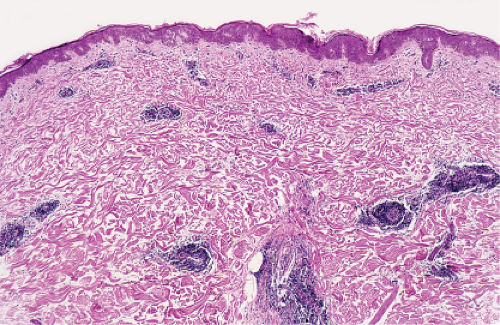

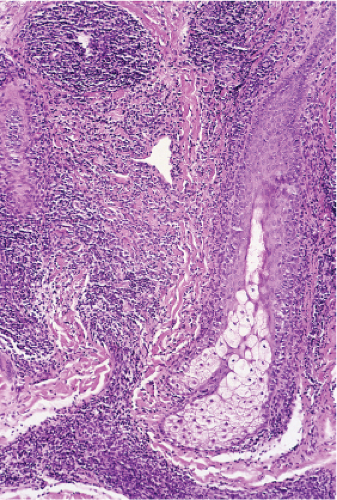

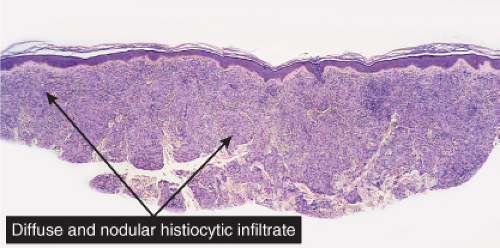

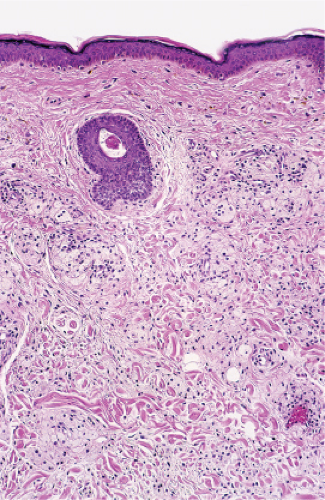

Fig. VC3.a. Lepromatous leprosy, low power. There is a diffuse to nodular infiltrate, nearly obliterating the architecture of the dermis. |

Fig. VC3.b. Lepromatous leprosy, medium power. The infiltrate is composed of large histiocytes as well as small lymphocytes. |

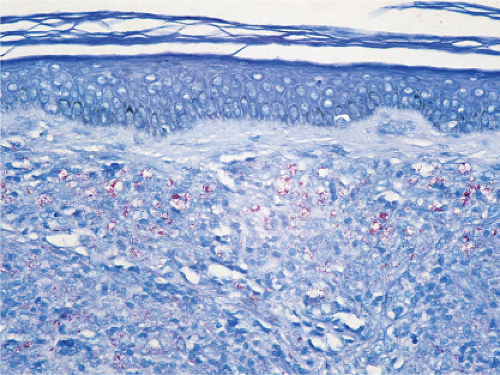

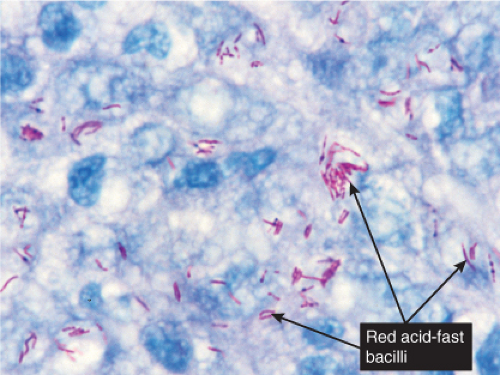

Fig. VC3.c. Lepromatous leprosy, medium power, Fite stain. Even at this magnification, the presence of acid-fast organisms can be appreciated. |

Fig. VC3.d. Lepromatous leprosy, high power, Fite stain. The organisms are arranged in clumps within the cytoplasm of the histiocytes. |

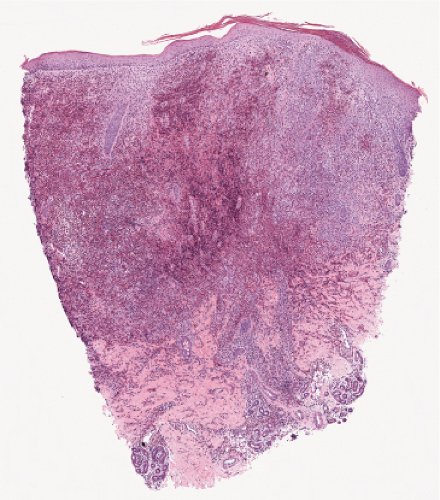

Fig. VC3.e. Langerhans cell Histiocytosis low power. There is a diffuse infiltrate spanning the dermis. |

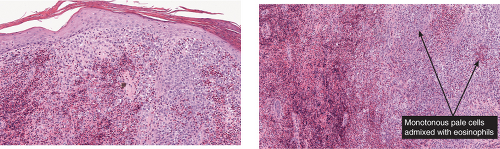

Fig. VC3.f,g. Langerhans cell Histiocytosis, medium power. There are many pale staining monotonous large cells as well as many eosinophils. The lesional cells are focally epidermotropic. |

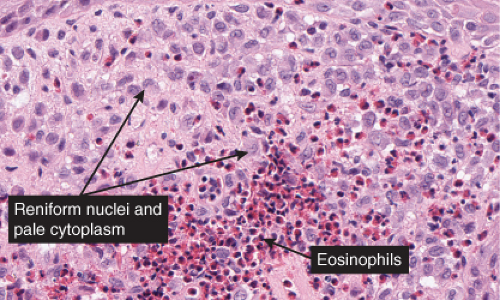

Fig. VC3.h. Langerhans cell Histiocytosis. The lesional cells are large with abundant pink cytoplasm and reniform nuclei. There is an admixture of inflammatory cells including occasional eosinophils. |

Histopathology

In the usual macular or infiltrative-nodular lesions, there is an extensive cellular infiltrate that is almost invariably separated from the flattened epidermis by a narrow grenz zone of normal collagen. The infiltrate causes destruction of the cutaneous appendages and extends into the subcutaneous fat. In florid early lesions, the macrophages have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and contain a mixed population of solid and fragmented bacilli. There is no macrophage activation to form epithelioid cell granulomas. Lymphocyte infiltration is not prominent, but there may be many plasma cells. In time, and with antimycobacterial chemotherapy, degenerate bacilli accumulate in the macrophages constituting the so-called lepra cells or Virchow cells which then have foamy or vacuolated cytoplasm. The Wade-Fite stain reveals that the bacilli are fragmented or granular and, especially in every chronic lesions, disposed in large basophilic clumps called globi. In lepromatous leprosy, in contrast to tuberculoid leprosy, the nerves in the skin may contain considerable numbers of leprosy bacilli, but remain well preserved for a long time and slowly become fibrotic. The histopathology of Lucio (diffuse) leprosy is similar, but with a characteristic heavy bacillation of the small blood vessels in the skin.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Histiocytosis X)

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) or histiocytosis X is characterized by a proliferation of dendritic or Langerhans histiocytes (31). If LCH occurs during the first year of life, it is usually characterized by significant, potentially fatal visceral involvement and classified as acute disseminated LCH (Letterer–Siwe disease). If LCH develops during early childhood, the disease is manifested predominantly by osseous lesions with less extensive visceral involvement and known as chronic multifocal LCH or Hand—Schüller–Christian disease. In older children and adults, LCH is usually of the chronic focal type, often presenting one or few bone lesions known as eosinophilic granuloma. Cutaneous lesions are very commonly encountered in Letterer–Siwe disease and occur occasionally in the two other forms. The cutaneous lesions usually consist of petechiae and papules. In some cases, there are numerous closely set, brownish papules covered with scales or crusts, involving particularly the scalp, face, and trunk. The clinical course and the prognosis of LCH are difficult to predict.

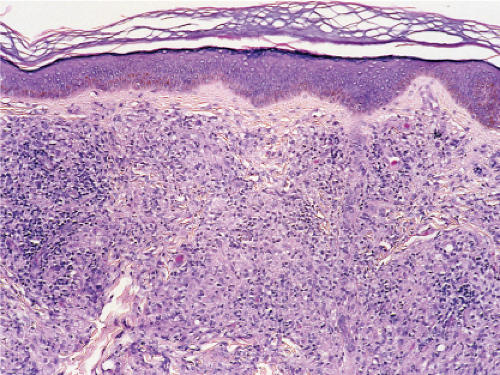

Histopathology

The key to diagnosis is identifying the typical Langerhans cell in the appropriate surroundings. The cell has a distinct folded or lobulated, often kidney-shaped nucleus. Nucleoli are not prominent, and the slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm is unremarkable. A typical clinical and light microscopic picture leads to a presumptive diagnosis; confirmation by typical S-100 or peanut agglutinin staining produces a diagnosis; a definite diagnosis requires either a positive CD1a stain or electron microscopic demonstration of Birbeck granules. Although three kinds of histologic reactions have been described in LCH histiocytosis’proliferative, granulomatous, and xanthomatous’only the first two are commonly seen. In general, the proliferative reaction with its almost purely histiocytic infiltrate is typical of acute disseminated LCH and a granulomatous reaction is usually present with chronic focal or multifocal LCH, as the name eosinophilic granuloma suggests. Xanthomatous lesions in the skin are decidedly rare. The proliferative reaction is characterized by the presence of an extensive infiltrate of histiocytes. The infiltrate usually lies close to or involves the epidermis, resulting in ulceration and crusting. Inflammatory cells are also present, most often lymphocytes but also eosinophils. The granulomatous reaction shows extensive aggregates of histiocytes often extending deep into the dermis, with variable eosinophils, multinucleated giant cells, neutrophils, lymphoid cells, and plasma cells may be present.

Xanthelasma

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

xanthelasma, xanthomas (usually nodular)

atypical mycobacteria

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI)

deep fungus infection

cryptococcosis

histoplasmosis

paraffinoma

silicone granuloma

talc & starch granuloma

annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (actinc granuloma)

lepromatous leprosy

Clin. Fig. VC3.b. Xanthelasma. Most often no underlying lipid abnormalities are present when patients present with these typical yellowish plaque on the eyelids.

Fig. VC3.i. Xanthelasma, low power. There is a diffuse infiltrate of pale-staining cells in the dermis.

Fig. VC3.j. Xanthelasma, high power. The lesional cells are large with abundant foamy cytoplasm. There is no admixture of inflammatory cells.

histoid leprosy

cutaneous leishmaniasis

rhinoscleroma (Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis)

histiocytosis-X

leukemia cutis (myeloid, myelomonocytic)

anaplastic large cell lymphoma (Ki-1)

reticulohistiocytic granuloma

malakoplakia

VC4 Diffuse Infiltrates, Plasma Cells Prominent

Plasma cells are found in the diffuse dermal infiltrate, though they may not be the predominant cell. Secondary syphilis may be predominantly perivascular and has been discussed as such in VA4. Other examples of this condition may present as a diffuse infiltrate.

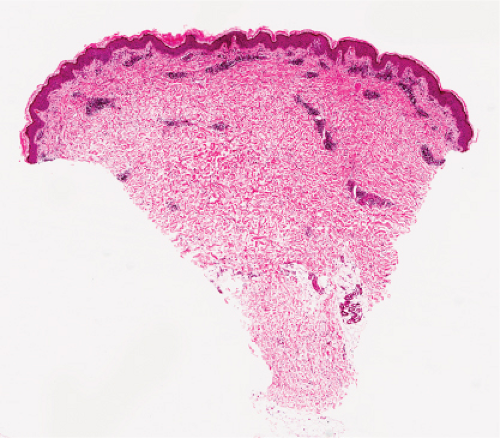

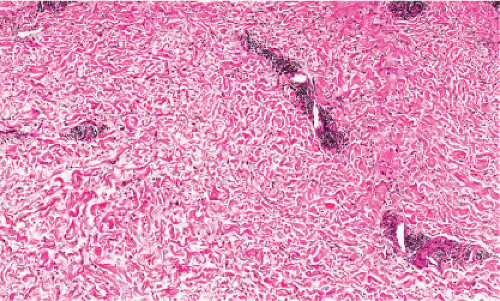

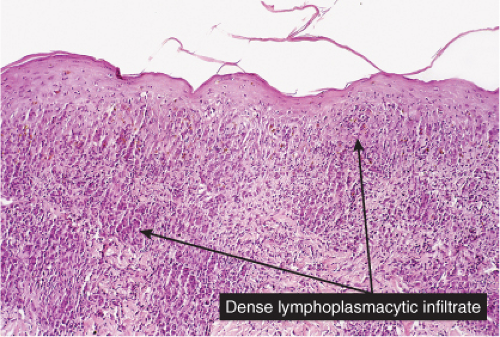

Fig. VC4.a. Secondary syphilis, low power. There is a dense diffuse and perivascular infiltrate in the superficial and deep dermis. |

Fig. VC4.b. Secondary syphilis, medium power. In this example, the infiltrate is bandlike in architecture and is composed mostly of plasma cells and lymphocytes. |

Secondary Syphilis

See Figs. VC4.a, b.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

insect bite reaction

plasmacytoma, myeloma

circumorificial plasmacytosis

Zoon’s balanitis

syphilis, secondary or tertiary

yaws, primary or secondary

acne keloidalis nuchae

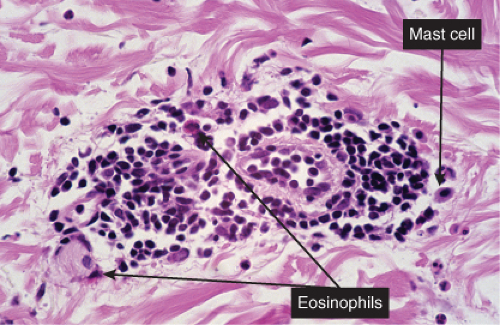

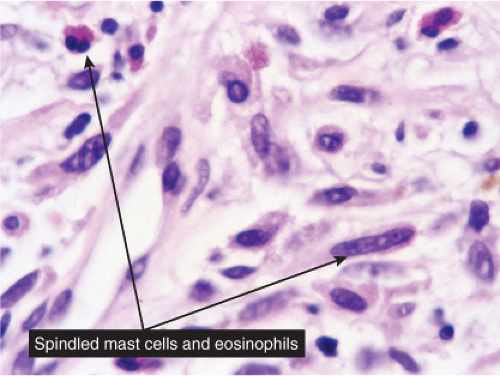

VC5 Diffuse Infiltrates, Mast Cells Predominant

Mast cells compose almost the entire dermal infiltrate. There may be an admixture of eosinophils. Urticaria pigmentosa is the prototype. (See sections IIIA2, IVE4, VIB10).

Urticaria Pigmentosa

See Figs. VC5.a–c.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis:

urticaria pigmentosa (nodular or diffuse) mastocytoma

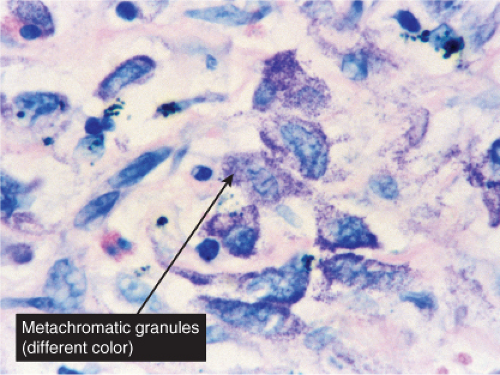

Fig. VC5.a. Urticaria pigmentosa, medium power. There is a diffuse cellular infiltrate in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. |

Fig. VC5.b. Urticaria pigmentosa, high power. The lesion cells have amphophilic cytoplasm with cytoplasmic granules, and a slightly eccentrically placed oval to round nucleus. |

VC6 Diffuse Infiltrates, Eosinophils Predominant

Eosinophils are prominent although not the only infiltrating cell. Lymphocytes are also found, and plasma cells may also be present. Eosinophilic cellulitis is a good example (32).

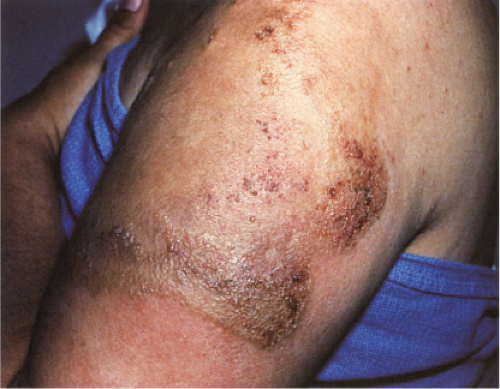

Eosinophilic Cellulitis (Wells’ Syndrome)

Clinical Summary

This rare dermatosis presents as a sudden eruption of a variable number of bright erythematous patches, which over a period of a few days expand into indurated erythematous plaques that may be painful. The overlying epidermis may produce vesicles or small blisters. The disease, if untreated, may persist for a few weeks or months and may be recurrent. Associated or provoking stimuli may include insect bites and cutaneous parasitosis, cutaneous viral infections and drug reactions, leukemic and myeloproliferative disorders, and atopic dermatitis and fungal infections. The patients are usually adults. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is usually present. The clinical appearance may mimic bacterial cellulitis (33).

Clin. Fig. VC6.a. Wells Syndrome.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|