34 Diagnosis and Treatment of Malignant and Premalignant Lesions

For melanoma, risk factors include family history, large congenital nevi, the familial atypical mole and melanoma syndrome (FAMMS; previously dysplastic nevus syndrome) (Figure 34-1) and sun exposure, particularly blistering burns in fair-skinned individuals. After initial biopsy, Breslow’s classification by depth of invasion is used to guide re-excision margins and the need for sentinel lymph node biopsy and to predict general survival rates.

Actinic Keratoses, Actinic Cheilitis, and Bowen’s Disease

Actinic keratoses (AK), actinic cheilitis, and Bowen’s disease (SCC in situ) are all caused by cumulative sun exposure and have the potential to become invasive squamous cell carcinomas. The rate of malignant transformation has been variably estimated but is probably no greater than 6% per AK over a 10-year period.1 On a spectrum of malignant transformation, Bowen’s disease is squamous cell carcinoma in situ before the squamous cell carcinoma becomes invasive. In one large prospective trial, the risk of progression of AK to primary SCC (invasive or in situ) was 0.6% at 1 year and 2.6% at 4 years. Approximately 65% of all primary SCCs and 36% of all primary BCCs diagnosed in the study group arose in lesions that had been previously diagnosed clinically as AKs.2

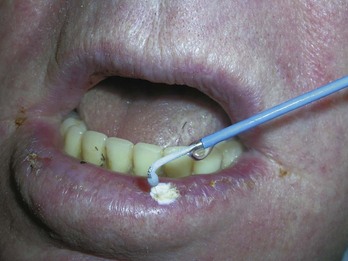

Actinic keratoses are rough scaly spots seen on sun-exposed areas that may be found by touch, as well as close visual inspection. Bowen’s disease appears similar to actinic keratosis, but tends to be larger in size and thicker with a well-demarcated border (Figure 34-2). Actinic cheilitis is equivalent to AK but found on the lips (Figure 34-3).

Treatment of Actinic Keratoses and Actinic Cheilitis

Electrodesiccation and Curettage (Single Cycle for AK)

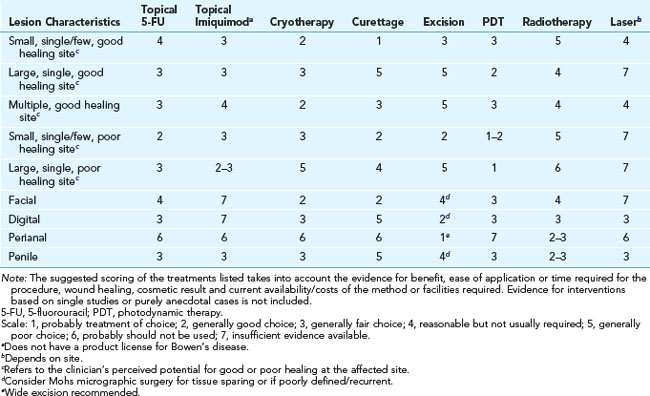

Treatment of Bowen’s Disease

The following is based on the guidelines from Cox et al.4:

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Diagnoses

FIGURE 34-6 Typical nodular BCC on the face of a 53-year-old man. Note the pearly borders and telangiectasias.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

FIGURE 34-7 Superficial BCC on the back with erythema, scale, and a thready border.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Removal

Elliptical Excision (Fusiform) (Figure 34-9)

Electrodesiccation and Curettage

Mohs Micrographic Surgery (Figure 34-13)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree