Dermatologic Diagnosis

John C. Hall MD

This chapter will discuss how to describe primary and secondary skin lesions, common dermatologic conditions associated with different anatomic locations, seasonal skin diseases, military dermatoses, and dermatoses found in patients of color.

Primary and Secondary Lesions

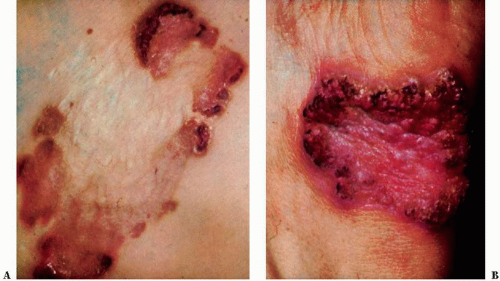

Most skin diseases have some characteristic primary lesions. It is important to examine the patient closely to find the primary lesion. Commonly, however, secondary lesions that are a direct result of overtreatment, excessive scratching, or infection have obliterated the primary lesions. Even in these cases, it is usually possible, through careful examination, to find some primary lesions at the edge of the eruption or on other, less irritated areas of the body (Fig. 3-1). Combinations of primary and secondary lesions also frequently occur.

Primary Lesions

Macules: Up to 1 cm and are circumscribed, flat discolorations of the skin (Fig. 3-2A). Examples include freckles, flat nevi, and some drug eruptions.

Patches: Larger than 1 cm and are circumscribed, flat discolorations of the skin. Examples include vitiligo, some drug eruptions, senile freckles, melasma, and measles exanthem.

Papules: Up to 1 cm and are circumscribed, elevated, superficial, solid lesions (Fig. 3-2B). Examples include elevated nevi, some drug eruptions, warts, and lichen planus. A wheal (hive) is a type of papule that is edematous and transitory (present <24 hours). Causes of wheals include drug eruptions, food allergies, numerous underlying illnesses, and insect bites.

Plaques: Larger than 1 cm and are circumscribed, elevated, superficial, solid lesions. Examples include mycosis fungoides and lichen simplex chronicus.

Nodules: Range in size (up to 1 cm) and are solid lesions with depth. They may be above, level with, or beneath the skin surface (Fig. 3-2C, D). Examples are nodular secondary or tertiary syphilis, basal cell cancers, dermatofibromas, and xanthomas.

Tumors: Larger than 1 cm and are solid lesions with depth. They may be above, level with, or beneath the skin surface (Fig. 3-2E). Examples include tumor stage of mycosis fungoides and larger basal cell cancers.

Vesicles: Up to 1 cm in size and are circumscribed elevations of the skin containing serous fluid (Fig. 3-2F). Examples include poison ivy, early chickenpox, herpes zoster, herpes simplex, dyshidrosis, and contact dermatitis.

Bullae: Larger than 1 cm and are circumscribed elevations containing serous fluid. Examples include pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid, poison ivy, and second-degree burns.

SAUER’S NOTES

1. One of the dermatologist’s tools of the trade is a magnifying lens. Use it.

2. A complete examination of the entire body is a necessity when confronting a patient with a diffuse skin eruption or an unusual localized eruption.

3. Touch the skin and skin lesions. You learn a lot by palpating, and patients appreciate that you are not afraid of “catching” the problem. (For the uncommon contagious problem, use precaution.)

4. When in doubt of the diagnosis, verify your clinical impression with a biopsy. The most frequent reason for a successful malpractice suit in dermatology is failure to diagnose.

5. Do not underestimate the importance of adequate lighting.

6. Dermoscopy is a new tool that is mainly used to evaluate pigmented lesions. It combines diascopy and magnification and is useful in diagnosing melanoma as well as deciding which tumors need a biopsy. Diascopy is a test to observe change in color after compression of a skin condition with a clear plastic or glass slide. If an observer has significant experience in dermoscopy, it is useful when deciding whether a lesion is truly benign or not.

7. There are computerized systems that will soon be available to evaluate multiple variables of pigmented tumors in vivo to decide whether a biopsy is necessary.

8. Serial photography systems have been shown by some authors to be useful when determining which pigmented tumors have changed significantly enough over time to warrant a biopsy.

Pustules: Vary in size and are circumscribed elevations of the skin containing purulent fluid (Fig. 3-2G). Examples include acne, pustular psoriasis, and impetigo.

Petechiae: Range in size (up to 1 cm) and are circumscribed deposits of blood or blood pigments. Examples are thrombocytopenia, vasculitis, and drug eruptions.

Purpura: A circumscribed deposit of blood or blood pigment that is larger than 1 cm in the skin. Examples include senile purpura, drug eruptions, bleeding diatheses, chronic topical and systemic corticosteroid use, and vasculitis.

Secondary Lesions

Scales: Shedding, dead epidermal cells that may be dry or greasy. Examples are seborrhea (greasy) and psoriasis (dry).

Crusts: Variously colored masses of skin exudates of blood, serum, pus, or any combination of these (Fig. 3-3A). Examples include impetigo, infected dermatitis, nummular eczema, or any area of excoriation.

Excoriations: Abrasions of the skin, usually superficial and traumatic. Examples are scratched insect bites, scabies, eczema, and dermatitis herpetiformis.

Fissures: Linear breaks in the skin, sharply defined with abrupt walls. Examples include congenital syphilis, interdigital tinea pedis, and hand eczema.

Induration: Woodiness or hardness as seen in infiltrating tumors such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, cutaneous metastasis, lymphoma, scleroderma, or hypertrophic scars.

Ulcers: Variously sized and shaped excavations in the skin extending into the dermis or often deeper that usually heal with a scar. Examples include stasis ulcers of legs, ischemic leg ulcers, pyoderma gangrenosum, and tertiary syphilis.

Scars: Formations of connective tissue replacing tissue lost through injury or disease. Examples are discoid lupus, lichen planus in the scalp, and third-degree burns.

Keloids: Hypertrophic scars beyond the borders of the original injury (Fig. 3-3B). They are elevated, can be progressive, and usually are the result of some sort of trauma in the skin. Keloids are more common in darker-skinned people. They are common on the upper torso, neck, and with body piercing (especially with piercings of the earlobe). Rarely, keloids can occur spontaneously. Any type of full-thickness skin trauma can heal with a keloidal scar. They are unsightly and can be numb, pruritic, or painful.

Lichenification: A diffuse area of thickening and scaling with a resultant increase in skin lines and markings (Fig. 3-3C). It is often seen in atopic dermatitis or any area chronically rubbed or scratched.

Several combinations of primary and secondary lesions commonly exist on the same patient. Examples are papulosquamous lesions of psoriasis, vesiculopustular lesions in contact dermatitis, and crusted excoriations in scabies.

Special Lesions

Some primary lesions, limited to a few skin diseases, can be called specialized lesions.

Burrows: Very thin and short (in scabies) or tortuous and long (in creeping eruption) tunnels in the epidermis.

Comedones or blackheads: Plugs of whitish (whiteheads or closed comedones) or blackish (blackheads or open comedones) sebaceous and keratinous material lodged in the pilosebaceous follicle, usually seen on the face, chest, or back and, rarely, on the upper part of the arms. Examples include acne and Favre-Racouchot on sun-damaged skin in the temporal areas. These are a hallmark of chloracne. Chloracne is caused by exposure to hydrocarbons such as those found in cutting oils and Agent Orange.