Dermatitis

Lilla Landeck

Lynn Baden

Among industrialized countries, dermatitis (synonym: eczema) is one of the most frequent dermatologic diagnoses presenting for treatment. By definition, the term dermatitis describes a noncontagious skin disease characterized by inflammation in the epidermis and upper dermis with multiple etiologies. Although the terms dermatitis and eczema are often used interchangeably, “dermatitis” frequently refers to the more acute form of skin inflammation with rapid improvement, while “eczema” tends more to illustrate a chronic relapsing course.

A common term associated with dermatitis is skin barrier function, which refers to the damaged skin barrier accompanied by inflammation of the skin and vice versa. The epidermal skin barrier is discussed in detail in Chapter 4. Skin exposure, either to substances that dissolve intercellular lipids (e.g., organic solvents/detergents) or destroy keratinocytes, stresses the skin barrier function. In cases of chronic skin damage, barrier function may be exhausted, resulting in the damage of chronic forms of eczema. Skin inflammation can be classified according to the sequence of inflammation into an acute phase with clinical features such as erythema, edema, exudation, and/or vesiculation and a chronic state that presents clinically with scaling and lichenification. Both can be accompanied by pruritus.

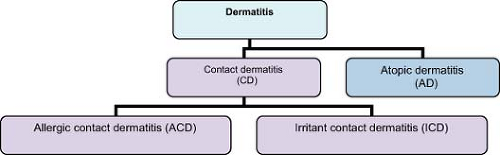

Further attempts to categorize eczema include reference to anatomical localization (e.g., hand, foot, generalized); specific clinical features (nummular, asteatotic); and in some cases, the specific subtype of dermatitis such as shown in Figure 15-1. Because eczema may originate from a mixture of etiological causes with similar morphological/clinical and histopathological appearances, specific differentiation can be difficult. It is possible, especially with hand eczema, for any or all diagnoses to play partial roles in driving the eczema.

Diagnosis of eczema depends on patient’s history, clinical distribution, and morphology of skin lesions, and the exclusion of other diagnoses.

Therapy is generally based on three principles: avoidance of possible triggers, restoration of impaired epidermal barrier function with emollients, and treatment with anti-inflammatory therapeutics. The most common first-line anti-inflammatory medications are topical corticosteroids. They are easy to apply and utilized in different potencies and vehicles. Side effects of topical corticosteroids are minimized by appropriate selection and utilization. These will be further discussed in the individual sections below.

Atopic Dermatitis

|

A mother presents with concerns about her 16-month-old son: “Since the beginning of wintertime when we turned on the heat, he scratches himself all night long awaking frequently and crying.” Upon examination it is noted that the child is continuously scratching. The skin is erythematous, edematous, and reveals exudative crust and excoriations (Fig. 15-2). The face, the neck, and the flexural areas of the extremities are most prominently affected. Moreover, the mother describes worsening of the skin after giving her son cow’s milk or egg-containing foods.

Background

The word atopy is derived from the Greek word “ατoπiα” and depicts a condition “out of place/placelessness,” or unusual. From a medical point of view atopy describes a polygenic inherited disposition to develop at least one of the following disorders: atopic dermatitis (AD), allergic rhinitis (AR), or allergic asthma (AA). Atopic disorders (AD, AR, AA) are marked by a manifestation of the interface of the organism to the environment (skin, mucosal skin, lungs) and have in common genetically based increased susceptibility to react to environmental factors. it appears that atopy is more prevalent in highly industrialized societies and higher socioeconomic classes.

AD is characterized by a genetically based hypersensitivity of the skin with predisposition to develop eczema in typical anatomic localizations according to stage. Current estimates show that 15% of schoolchildren and 2% of adults in industrialized countries suffer from AD, with a slight predominance of females. A myriad of possible intrinsic and extrinsic triggers include stress, aeroallergens, microbial products, and/or food allergens. The manifestation of the disease is typically most severe in childhood, with a chronic relapsing course and improvement in most cases occurring during adulthood. Important hallmarks comprise pruritus and xerosis cutis.

Key Features

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is characterized by a pruritic, chronic, relapsing eczema.

Often, there is a personal and/or family history of atopy and xerosis.

AD has a genetic basis (filaggrin mutation) with variable expression depending on environmental factors.

Typically, three stages with different morphologic appearance and anatomic distribution of flares to distinguish them: infantile, childhood, adulthood.

Most often affected individuals are infants and children. Upon reaching puberty, prevalence decreases.

Mainstays of treatment are the avoidance of triggers, maintenance or restoration of epidermal barrier function with emollients, and topical corticosteroids during flares.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis and etiology of the disease are still not fully understood. Most likely the AD phenotype results from a complex interplay between genetic, immunologic, metabolic, and neuroendocrine alterations and their interaction with the environment.

Genetics

It has long been recognized that inheritance of atopy is on a polygenetic basis with variable expression influenced by environmental factors. Recently, mutations in multiple regions of the filaggrin gene, leading to dysfunction of the filaggrin protein, an essential component in epidermal barrier function, were reported. Not only do filaggrin defects seem to be at least partially responsible

for AD, they also play a role in the pathogenesis of ichthyosis vulgaris, a xerotic skin condition seen in conjunction with AD in ∼8% of cases.

for AD, they also play a role in the pathogenesis of ichthyosis vulgaris, a xerotic skin condition seen in conjunction with AD in ∼8% of cases.

Barrier-disrupted Skin

AD skin is characterized by severe dryness due to alterations in composition of intercellular lipids and an impaired barrier function of the epidermis, with resulting high transepidermal water loss and lower skin surface hydration levels. A combination of barrier disruption and AD makes the skin highly susceptible to environmental factors such as irritants, allergens, and microbes.

Immunologic Alterations

AD shows a multifaceted immunologic picture with immune deficiency and immune hyperreactivity. Selective immune deficiency is observed by the trend to develop certain skin infections, such as herpes simplex virus. In contrast, approximately 70% of AD patients suffer from increased IgE levels, which were directly correlated to the disease activity. While consensus exists that among atopic individuals there is a heightened tendency to develop IgE-type-I antibodies to environmental factors, some authors have claimed a decreased type-IV cell-mediated immunity, which would lead to the observation of decreased rates of allergic contact dermatitis. However, recent publications showed atopic individuals to be at least as likely to have allergic contact dermatitis as nonatopics, probably because of the increased use of topicals and the eased penetration of allergens due to disrupted skin barrier.

Clinical Presentation

The majority of patients are infants and children. Up to 90% of cases arise before the age of 5 years. At each stage AD may show acute, subacute, or chronic skin changes. However, certain presentations are more common in specific stages. AD of infants and children is predominately an acute, exudative inflammation, with secondary excoriations. In adulthood, chronic inflammation with hyperkeratotic skin-thickening, lichenification (accentuated skin markings), and scaling are more prominent. Postinflammatory pigment changes, either hyper- or hypopigmentation, can be observed. Pruritus is almost always present. The typical anatomic distribution of AD varies by stages, changing over lifetime. AD lesions of infants are predominantly located on the face and the extensor surface of the extremities, while the childhood pattern is typified by flexural

involvement. For the adult with atopic dermatitis, the earlier classic locations are often involved, such as flexural areas (Fig. 15-3). There also is more frequent facial (especially eyelid) and hand/foot eczema.

involvement. For the adult with atopic dermatitis, the earlier classic locations are often involved, such as flexural areas (Fig. 15-3). There also is more frequent facial (especially eyelid) and hand/foot eczema.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria for AD are based primarily on clinical presentation, patients/family history, and the exclusion of other disease entities. Hanifin and Rajka compiled, in the early 1980s, important diagnostic features, which attained international recognition. Since that time, the criteria have evolved into the current schema. A consensus conference, convened by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) suggested the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of AD given in Table 15-1.

Diagnosis is made using the above-mentioned criteria. In questionable cases, a supportive biopsy with histopathologic interpretation may help, especially when other differential diagnoses, such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma must be excluded. Biopsy is not appropriate to classify the eczema according to a specific etiology because of many histologic similarities between eczema types. Analytical measurement of total IgE is used to distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic forms of AD. Extrinsic AD, with elevated serum IgE, is characterized by a personal or family history of respiratory allergy and can be found in 70% of AD individuals. Patients without IgE reactivity or obvious allergic respiratory conditions have intrinsic AD.

Differential Diagnoses

In children: seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis (allergic or irritant), psoriasis, scabies, familial keratosis pilaris, Langerhans cell histocytosis, congenital ichthyosis

In adults: seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis (allergic or irritant), psoriasis, scabies, familial keratosis pilaris, tinea manuum, asteatotic eczema, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, secondary syphilis

Therapy

The inherited hypersensitivity and the disposition of the skin to develop eczema is a lifelong condition. Thus, whether disease is active or not, avoidance of potential triggers and maintenance of physiologic skin barrier function with hydration (e.g., with urea 3% to 5% as an ingredient) and thick

emollients is essential. Generally, patients with AD should limit potentially skin-irritating activities such as wet work and contact to chemicals/detergents. Moreover the use of mild, perfume-free, nonalkali soaps is recommended. Although bathing dries the skin, patients often sense a general relief and reduction of pruritus while immersed. Hence recommendation for bathing patients includes the immediate reapplication of moisture. Use of a cream containing ceramides (either prescription or over-the-counter) is helpful for many patients.

emollients is essential. Generally, patients with AD should limit potentially skin-irritating activities such as wet work and contact to chemicals/detergents. Moreover the use of mild, perfume-free, nonalkali soaps is recommended. Although bathing dries the skin, patients often sense a general relief and reduction of pruritus while immersed. Hence recommendation for bathing patients includes the immediate reapplication of moisture. Use of a cream containing ceramides (either prescription or over-the-counter) is helpful for many patients.

Table 15-1 Diagnostic Features of Atopic Dermatitis as Suggested by the AAD Consensus Conference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reduction of house dust mites with vacuum cleaning, removal of carpets and curtains, and the use of special bed covers seems to improve the skin condition as well. Cotton clothing is preferred to wool and synthetics. Avoidance of specific food products such as eggs, milk, or nuts in those patients who experience a flare when eating them can be helpful too.

In case of active flares, intensity and distribution of skin lesions, as well as specific symptoms, determine the therapeutic choices. The mainstay of treatment for pruritus is antihistamines whereas corticosteroids are used to gain control of skin inflammation. Advantages of topical corticosteroids include ease of application, possibility of combination with other therapies (e.g., phototherapy), and the opportunity of choices with regard to ingredient potency. Rapid flares are best treated with 5 days of a medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroid ointment. Application should be once to twice a day. Once disease control is achieved, the topical corticosteroid can be tapered to a less-potent class and eventually withdrawn. Adjustment of steroid class when used in the groin area and the face should be considered, as these areas are more vulnerable for cutaneous atrophy. Alternating therapy with topical immunomodulators (calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, FDA approved for patients > 2 years) or days of therapeutic pause decrease the risk of cutaneous atrophy. Especially for moderate to severe AD, phototherapy in combination with topical therapy can improve AD. Appropriate regimens comprise narrow-band UVB and PUVA (Psoralen + UVA). Disadvantages of phototherapy are the inconvenience of traveling to clinic for tri- or bi-weekly treatments, as well as the risk of photoaging and/or induction of cutaneous malignancies and sunburns.

If a patient is not already applying topical corticosteroid twice daily to all affected areas, a regimen of triamcinolone 0.1% cream dispensed in a 454-g jar often is helpful. This allows aggressive application topically as in many cases patients do not have enough to adequately treat affected areas (see Chapter 2). Using triamcinolone 0.1% in conjunction with open wet dressings (Table 15-2) is very helpful for patients able to apply them once or twice daily.

For severe, unresponsive AD, systemic use of corticosteroids may be employed judiciously. Chronic utilization of oral corticosteroids should be avoided because of possible systemic complications. Tapering should be done carefully, because abrupt cessation of therapy may be associated with a rebound flaring.

Another helpful systemic medication in severe AD is systemic cyclosporine in daily dosage of 2 to 5 mg/kg. It can improve the condition quickly, but its usefulness may be limited by side effects. Less often used systemic treatments include methotrexate and azathioprine.

Systemic antistaphylococcal therapy is helpful for all stages of infected AD. Antibiotics of choice are oral cephalosporin and dicloxacillin in doses of 250 mg four times daily for adults, or 125 mg twice a day (25 to 50 mg/kg/day divided into two doses) for young children. Future treatments may include the use of IgE-binding biologics for a subgroup of patients. A simple method to reduce bacterial colonization is bleach baths. These are simple and cost effective. In a standard 40-gallon bathtub, fill with comfortable temperature (not hot) water. Add ½ cup bleach (such as Clorox). Soak for ∼10 minutes. Gently

rinse the face with a washcloth, keeping eyes closed. Repeat this as maintenance 2 to 3 times weekly.

rinse the face with a washcloth, keeping eyes closed. Repeat this as maintenance 2 to 3 times weekly.

Table 15-2 Open Wet Dressings | |

|---|---|

|

“At a Glance” Treatment

Maintenance therapy:

Patients with AD should limit potentially skin-irritating activities such as wet work and contact to chemicals/detergents.

Use mild, perfume free, nonalkali soaps.

Bleach baths 2 to 3 times weekly.

Following bathing, patients must moisturize immediately.

Apply cream containing ceramides (either prescription [Atopiclair/Mimyx] or over-the-counter [Cerave]).

Topical mild or moderate potency corticosteroid application immediately with dermatitis flare, after resolution return to moisturizing regimen as above.

Alternate maintenance: topical tacrolimus (Protopic) to AA BID × 1 to 6 weeks until dermatitis clear, then apply as maintenance to prior AA twice weekly.

Mild or moderate active flares:

The mainstay of treatment for pruritus is antihistamines whereas corticosteroids are used to gain control of skin inflammation.

Rapid flares are best treated with 5 days of a medium-to high-potency topical corticosteroid ointment. Application should be once to twice a day. Once disease control is achieved, the topical corticosteroid can be tapered to a less potent class and eventually withdrawn.

Adjustment of steroid class when used in the groin area and the face should be considered, as these areas are more vulnerable for cutaneous atrophy.

Alternating therapy with topical immunomodulators (calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, FDA approved for patients >2 years) may be helpful.

Moderate to severe AD: consider combination topical and ultraviolet therapy.

Narrow-band UVB and PUVA (Psoralen + UVA).

Severe, unresponsive AD:

Topical triamcinolone cream: dispense 454-g jar. Advise open wet dressings to affected areas as described.

Systemic use of corticosteroids may be employed judiciously. Chronic utilization of oral corticosteroids should be avoided. Taper carefully.

Systemic cyclosporine in daily dosage of 2 to 5 mg/kg.

Less often used systemic treatments include methotrexate and azathioprine.

Systemic antistaphylococcal therapy is helpful for all stages of infected AD:

Antibiotics of choice are oral cephalosporin and dicloxacillin in doses of 250 mg four times daily for adults, or 125 mg twice a day (25 to 50 mg/kg/day divided into two doses) for young children.

Bleach baths 2 to 3 times weekly: put ¼ to ½ cup bleach in a standard bathtub. Soak for at least 10 minutes.

Course and Complications

In most affected infants and children, the frequency of active inflammatory flares decreases with age until the teens. Around two thirds of childhood AD cases clear in early adolescence or become symptom free. Of note, patients with childhood AD are at risk for the later development of hand eczema, allergic rhinitis, and/or asthma. A minority of patients show a chronic relapsing course beyond puberty. Frequently these patients develop a moderate-severe AD accompanied by other atopic features such as allergic rhinitis and/or allergic asthma.

Even with diminution of active AD skin lesions, the inherited hypersensitivity and the disposition of the skin to develop eczema is a lifelong condition. This can be important when choosing a profession. Avoidance of potential triggers such as frequent contact to water, detergents, and chemicals is a lifelong necessity.

Infections

Patients with AD are prone to develop skin infections. One specific feature of AD is dense colonization with Staphylococcus aureus. In addition to bacterial infections, patients with AD show an increased prevalence of viral infections from herpes-, pox-, and papillomavirus groups. Typical viral infections include eczema herpeticum, molluscum contagiosum, and flat warts. There is also an increased susceptibility to superficial fungal infections, especially Trichophyton rubrum and Pityrosporum ovale.

Dermatologic referral becomes useful when skin lesions do not resolve or when they exacerbate with common treatment options.

In cases of severe infections, (e.g., zoster ophthalmicus); systemic involvement (e.g., erythroderma); neuropsychiatric impairment (e.g., depression); or when side effects of pharmacotherapy are unacceptable, consultation with the appropriate specialist is essential.

Erythroderma

In severe cases of AD, a significant exacerbation may lead to an erythrodermic skin condition possibly complicated by cardiac and renal compromise.

Neuropsychiatric Changes

The intractable course of AD may result in a diminished sense of personal well-being and self-esteem, leading to depressive mood and withdrawal from social interaction.

Complication of Treatments

The use of topical immunosuppressive therapy can worsen skin infections. Moreover the chronic use of topical corticosteroids leads to poor wound healing, skin atrophy, and telangiectasias. Regular application of corticosteroids to the face can cause rosacea, acneiform skin eruptions, and hypertrichosis.

Allergic reactions to vehicles in products, such as wool alcohols or preservatives, are also possible. Oral immunosuppressive steroid therapy may lead to osteoporosis, Cushing syndrome, and hip necrosis, and the use of cyclosporine can lead to hypertension and renal failure.

Allergic reactions to vehicles in products, such as wool alcohols or preservatives, are also possible. Oral immunosuppressive steroid therapy may lead to osteoporosis, Cushing syndrome, and hip necrosis, and the use of cyclosporine can lead to hypertension and renal failure.

Staphylococcal colonization and infection can drive chronic AD. Be sure to assess and treat skin infection.

For spreading, painful dermatitis consider eczema herpeticum.

Open wet dressings are exceedingly helpful for acute, severe dermatitis.

ICD9 Codes

| 706.8 | Other specified diseases of sebaceous glands |

| 372.53 | Conjunctival xerosis |

| 691.8 | Other atopic dermatitis and related conditions |

| 692.0 | Contact dermatitis and other eczema due to detergents |

| 692.1 | Contact dermatitis and other eczema due to oils and greases |

| 692.2 | Contact dermatitis and other eczema due to solvents |

| 692.3 | Contact dermatitis and other eczema due to drugs and medicines in contact with skin |

| 692.4 | Contact dermatitis and other eczema due to other chemical products |

| 692.5 | Contact dermatitis and other eczema due to food in contact with skin |

| 692.6 | Contact dermatitis and other eczema due to plants (except food) |

| 692.70 | Unspecified dermatitis due to sun |

| 692.71 | Sunburn |

| 692.72 | Acute dermatitis due to solar radiation |

| 692.73 | Actinic reticuloid and actinic granuloma |

| 692.74 | Other chronic dermatitis due to solar radiation |

| 692.75 | Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (dsap) |

| 692.76 | Sunburn of second degree |

| 692.77 | Sunburn of third degree |

| 692.79 | Other dermatitis due to solar radiation |

| 692.81 | Dermatitis due to cosmetics |

| 692.82 | Dermatitis due to other radiation |

| 692.83 | Dermatitis due to metals |

| 692.84 | Contact dermatitis and other eczema due to animal (cat) (dog) dander |

| 692.89 | Contact dermatitis and other eczema due to other specified agents |

| 698.9 | Unspecified pruritic disorder |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree