Abstract

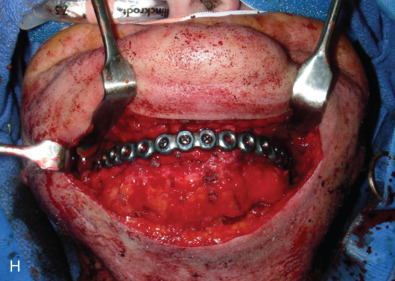

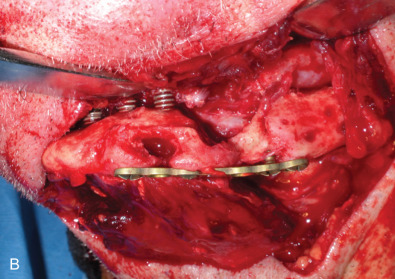

The evolution of mandibular fracture complications – infection, delayed union, malunion, nonunion, malocclusion, TMJ disorders, paresthesia, etc. – along with causes – the injury itself, inadequate or inappropriate treatment, patient compromise, misadventure, etc. – are described. Contemporary management is outlined with a series of illustrative examples. An underlying theme is that the treatment of failed rigid fixation, the standard of care today, is a bigger plate and more screws.

Keywords

mandibular fracture, complications, nonunion, malunion, infected nonunion

The Problem

The mandible is a complex structure involved in many functions. It is a hoop-like bone which gives form to the lower face. It supports the lower teeth, tongue, lips, and some of the muscles of facial expression. Through it runs the sensory innervation of the chin and lower lip. It is suspended in space by paired muscles of mastication which functionally move the jaw through mastication, expression, and speech. It articulates with the skull base through paired diarthrodial joints with interposed menisci. It is involved with facial form and appearance, mastication and movement, speech, sensation, and expression. As such, it is one of the most unforgiving structures, certainly bones, in the body as any alteration of one or more of these functions is not likely to be ignored.

Nature of Complications

There are complications of injury: traumatic loss of a tooth, severance of an inferior alveolar nerve. There are complications that occur with proper treatment: approach scars, paresis, infection. There are complications of inadequate or inappropriate treatment: infection, delayed, nonunion or malunion from inadequate reduction and/or fixation. There are surgical misadventures: pithing the nerve with a screw during the process of applying fixation. There are complications of no treatment: malunion, nonunion, infection. Treatment is designed to minimize or overcome the potential complications of injury, not introduce additional ones.

Evolution of Complications

In the 19th and early 20th century, the measure of success for mandibular fractures was functional union. One accepted infection, loss of teeth, sequestration of bone, paresthesia, etc. as the complications of injury. Suppuration of open fractures, exfoliation of teeth, bone fragments, were all considered part of the process. One only has to read the accounts of treatment and outcomes during the 19th century to see how far we have come.

The great advance to avoid and/or treat infection was immobilization of the jaws. Gunning and Bean utilized gutta percha splints. Lewis Gilmer introduced maxillomandibular fixation (MMF). These closed techniques of immobilization – later with the addition of skeletal pins – formed the basis of mandibular fracture treatment prior to antibiotics. Indeed, the great giants of maxillofacial trauma care were masters of the closed reduction. They knew how to reduce and immobilize the mandible without resorting to open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). The first edition of the Kazanjian and Converse classic text The Surgical Treatment of Facial Injuries is replete with descriptions of the closed techniques for the management of mandibular fractures.

The Antibiotic Era

With the advent of antibiotics, ORIF of open fractures in the tooth-bearing region emerged as a supplement to MMF. Stainless steel wire was used to maintain alignment, particularly for proximal control. By this time, the main complication in a properly managed mandibular fracture (MMF alone or MMF+ORIF or skeletal pin fixation) was “infection,” usually related to a tooth or dead bone. Nonunion, delayed and malunion often resulted. It was not uncommon to have prolonged periods of treatment, often lasting a year or more. Initial management – MMF+ORIF or X-fix – followed by “infection” with drainage, followed by debridement of nonvital teeth and/or bone, waiting 3–6 months after the cessation of drainage before bone grafting amounted to a year off one’s life.

Additionally, complications of condylar fractures in the form of ankylosis, malocclusion, and acquired retrognathia occurred. All required surgical correction.

As can be seen, complications of this era were primarily complications of injury or of “proper” treatment. Unless one failed to use adequate MMF with a “wire” ORIF or performed ORIF on a comminuted fracture (contraindicated prior to rigid fixation), operator error was most unusual.

The different areas of the mandible were not equal with respect to the incidence of complications. Angle fractures with teeth in the line of fracture were most prone to complication, with almost one-third having them. This occurred irrespective of whether they were done open or closed or whether the teeth involved were removed or retained. It remains true today.

It should be noted that treatment times, even for successful outcomes, often extended to 2 or 3 months as fractures were often not firm at 6 or 8 weeks. Following MMF, it was necessary to “rehabilitate” the jaw opening, a process often taking several more weeks.

Rigid Fixation

Rigid fixation (RIF) was introduced in Europe in the mid 1970s and North America in the mid 1980s. There were three distinct lineages: the AO, with reduction and rigid immobilization with stainless steel plates and screws – usually applied transfacial; the Luhr Vitalium system, also rigid immobilization but primarily transoral; and the transoral miniplate system of semirigid fixation popularized by Champy.

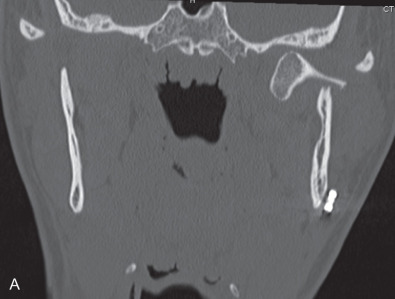

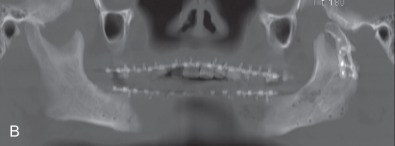

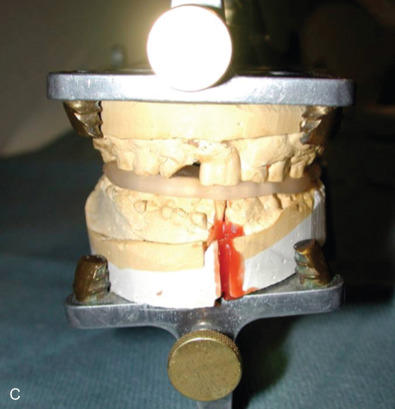

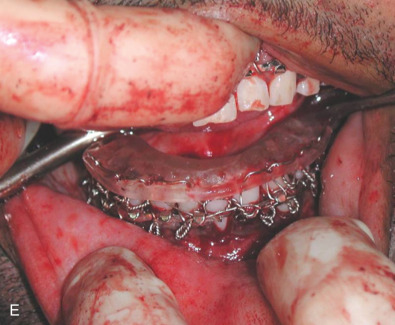

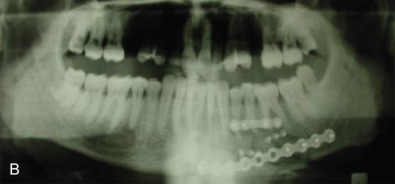

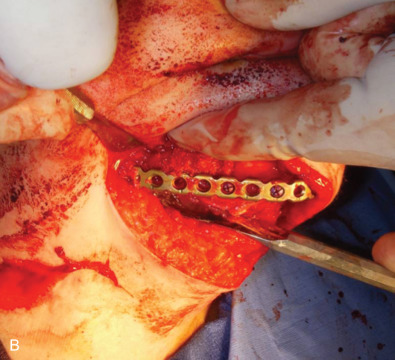

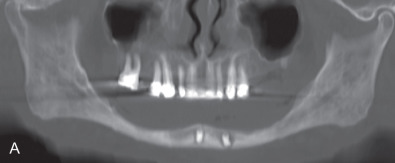

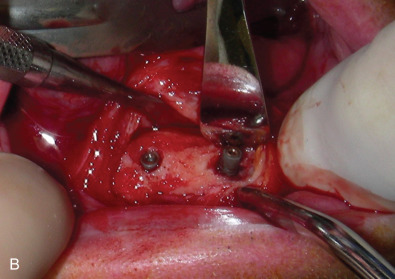

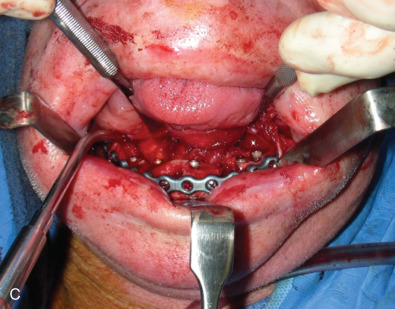

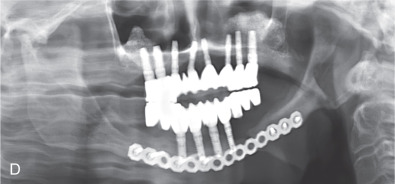

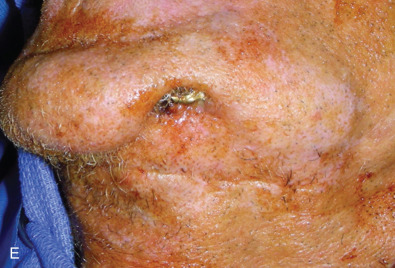

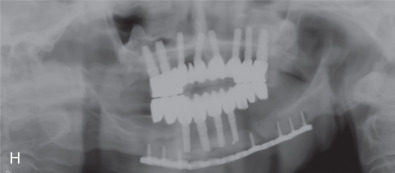

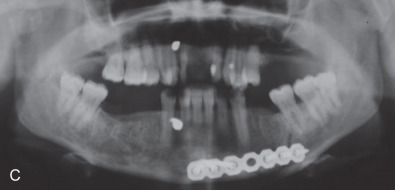

All of these systems allowed for convalescent function – life without MMF. RIF had the potential of dramatically shortening the course of treatment. However, its use was highly technique-sensitive with a steep learning curve. Thus, the incidence of complications increased dramatically due to operator error. Complications related to inadequate reduction – “the OIF” (open internal fixation … without the reduction) ( Figs. 1.16.1–1.16.3 ), inadequate fixation ( Figs. 1.16.4–1.16.7 ) and surgical misadventure ( Fig. 1.16.8 ) began to appear. Indeed, by the early 1990s operator error was the number one cause of mandibular fracture complications. Quite obviously, RIF is very unforgiving. When done poorly, one has a rigidly fixed mistake. The latest series of misadventures are related to the use of IMF screws. Bone-anchored arch bars will most likely be next. Not all believe that RIF and convalescent function is cost-effective with respect to the increased cost, potential for complications, and patient acceptance.

Incidence of Complications

As has been noted, this largely depends on what one considers a complication. Some feel that minor complications – loss of teeth, exposure of hardware, exfoliation of bone and modest delay to union – do not count, so long as union and some semblance of functional occlusion is achieved. Others consider complications to include anything that delays union or results in a suboptimal result. For example, transoral miniplate fixation of angle fractures has a 22% minor complication rate – exposure of hardware, loose screws, wound dehiscence – which can be simply managed in an office setting and do not affect the final outcome. The same treatment has a low (2%) major complication rate requiring return to the OR and major surgery in the form of application of additional RIF and/or bone graft.

Quite obviously, complications can depend on the one evaluating them. If that individual only considers union as an outcome, other complications will not be recognized.

It should be noted that studies involving complications of mandibular fractures are difficult to compare since some areas of the mandible are more prone to complications than others. Open fractures of the angle involving a tooth are most prone whereas closed fractures outside the tooth-bearing area are least prone. Other areas fall in between. In large series, all areas are included so the incidence may vary dramatically. Indeed, infection rates for ORIF of mandibular fractures have been reported to range from 3% to 30%. The most meaningful studies of the incidence of complications for varying treatments of mandibular fractures have been the angle fracture studies done by Ellis and coworkers. They compared different specific treatments of these fractures with comparable patient populations and similar surgical teams. As such, they compared “apples to apples vs. apples to oranges vs. considering all to be fruit.” These studies have clearly defined the incidence of complications of mandibular angle fractures with varying treatments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree