Distraction osteogenesis is a viable treatment option for patients with a cleft associated with severe maxillary retrusion. A rigid external distraction device and a hybrid internal maxillary distractor have been used to advance the maxilla allowing for predictable and stable results. These techniques can be applied by itself or as an adjunct to traditional orthognathic procedures. The technical aspects are presented. These procedures tend to be simpler and demonstrate great stability compared to traditional surgical methods. The reasons for stability are discussed.

Key points

- •

Distraction osteogenesis is a viable treatment option for patients with a cleft associated with severe maxillary retrusion.

- •

External and internal devices can be utilized.

- •

The external distraction device is utilized in cases with severe maxillary hypoplasia secondary to a cleft condition greater than 8 to 10 mm, with paranasal and malar deficiencies associated with severe scarring, existing pharyngeal flap, or previously failed advancement with a traditional approach.

- •

The main advantages of external maxillary distraction include large advancements and ease of vector control and adjustability during the activation process. The technique does not require a second surgical procedure for its removal. The requirement of an external halo and framework is its main disadvantage, although when properly utilized, it is an effective treatment option for otherwise challenging cases.

- •

Hybrid internal maxillary distractors are utilized in moderate cases of cleft-related maxillary hypoplasia. Virtual surgical planning and 3-dimensional design and manufacturing facilitates accuracy in device placement and vector selection. The hybrid intraoral distractor described in this article does not require a second operation for removal. A high maxillary osteotomy is difficult to use as the plate supporting the distractor, is anchored high in the maxillary/ malar bones, limiting it’s placement.

Introduction

The conventional treatment of dentofacial deformities in patients with cleft includes both orthodontic treatment and orthognathic surgery (OGS). The key surgical procedures required for the correction of these conditions include the Le Fort I osteotomy, sagittal split mandibular ramus osteotomies, and on occasion a genioplasty utilizing rigid fixation techniques. With these approaches, successful and predictable correction is usually obtained. However, the use of these techniques in patients with severe maxillary hypoplasia, either related to clefts or syndromic deformities, may fall short of expectations, as this particular group of patients includes additional challenges.

In patients with a cleft presenting with severe maxillary hypoplasia, marked mandibular excess, deficiency or asymmetry, a 2-jaw approach must be undertaken. The advantage of this surgical-orthodontic approach is that with 1 operation, the reconstructive team can provide the patient with close to ideal occlusion and markedly improved function and aesthetics. At the time of OGS, the surgeon has the added advantage of access to the nasal cavity to address the deviated septum, large turbinates, and residual nasal floor defects. In addition, the alveolar segments (when separated) can be approximated in such a way to facilitate the closure of nasolabial fistulas with locally elevated flaps while concurrently reconstructing the alveolar cleft with bone graft. The 2-jaw OGS approach can limit the extent of the maxillary advancement. However, it is recognized that patients undergoing OGS in which multiple segments are used present a higher risk to stability and surgical complications. These complications may include instability of bony translation or loss of individual teeth or bone segment loss secondary to vascular compromise. It has been reported that the risks for complications after Le Fort I maxillary surgery are about 4% in patients without a cleft. However, for patients with orofacial clefts and other deformities, this increases to about 25%. The maxillary advancement in patients with a cleft can be unstable, and the tendency for long-term relapse is high compared with that in noncleft patients. In addition, patients with orofacial clefts have mandibles that are of normal size or slightly smaller. For this reason, in many patients in whom the maxilla is extremely hypoplastic, the surgeon may choose to sagittally correct both the maxilla and mandible during OGS, thereby increasing the complexity of the operation.

Conventional orthognathic surgical procedures in this challenging group of patients should be done with the utmost care, and alternative treatments should be explored. In 1992, McCarthy and colleagues introduced the use of distraction osteogenesis (DO) in the craniofacial skeleton. Since that time, the technique has been applied to all of the bones of the craniofacial skeleton as detailed in this issue of Clinics in Plastic Surgery. It is now the treatment of choice for patients with craniofacial conditions such as Crouzon syndrome and Apert syndrome as well as hemifacial microsomia. , In addition, the technique has been successfully applied to patients with severe maxillary hypoplasia secondary to orofacial clefts.

Molina and Ortiz-Monasterio were the first to report maxillary distraction osteogenesis by means of elastic traction with an orthopedic face mask. Although this approach appeared promising, the results were disappointing. An external cranially fixed halo (rigid external distractor –RED) was developed as a point of anchorage to advance the maxilla and midface. The maxilla is connected with surgical wires through the dentition by an intraoral splint with removable traction hooks to the halo device. This distraction system utilizes both bone and dental anchorage and provides stable maxillary advancement in patients with severe hypoplasia of the lower midface. In addition the technique is relatively simple, with low morbidity, predictable, and has shown stable long-term results. , , ,

The benefits of distraction for correction of severe maxillary hypoplasia in patients with a cleft are well appreciated, but the benefits and limitations of internal versus external devices remain topics of active debate. Hybrid internal maxillary distractors (HIMXDs) can be used to correct deficiencies at or just above the Le Fort I level. They can be more technically demanding to place because of limitations in bone stock and surgical exposure. The benefits of the HIMXDs include: greater rigidity of the hybrid device leading to an earlier return to function and ease of maintaining the devices during the consolidation phase Furthermore, the device described in this article does not require a secondary procedure for removal. Cases requiring major advancements and significant control in 3 dimensions are better suited for RED. Recommendations for case selection are summarized in Table 1 .

| Recommendations | RED | HIMXD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| 1. Intact neurocranium | ✔ | n/a | n/a | |

| 2. Adequate dentition | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 3. Maxillary edentulous patients | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 4. Primary and transitional dentition | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 5. Small mouth aperture | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 6. Ideally well aligned arches with orthodontic appliances | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 7. Requires a dental borne splint and/or orthodontic appliances for fixation of the device | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 8. Requires an occlusal splint | ✔ | ? | ||

| 9. Mandible with normal size and position | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 10. Maxillary deficiency with overjet of 8–10 mm or more | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 11. Maxillary deficiency with overjet of 10 mm or more | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 12. Maxillary deficiency with severe malar and infraorbital deficiency | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 13. Severe palatal and lip scarring from previous surgeries | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 14. Pharyngeal flap | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 15. Severe airway issues related to maxillary hypoplasia | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 16. Ideal time late adolescence, can be done in growing patients with the understanding that repeat surgery might be required | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 17. Virtual surgical planning recommended | ? | ✔ | ||

| 18. Can be done before finishing OGS | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 19. Can be done in combination with OGS | ✔ | ✔ | ||

The surgical protocol for maxillary distraction utilizing a RED device and HIMXDs will be described.

Presurgical orthodontic alignment of the dentition and the fabrication of a tooth-supported intraoral splint

Presurgical Orthodontics

Ideally, all patients are prepared like any other patient undergoing OGS. Orthodontic treatment aligns the dentition and restores dental arch form. In patients with primary or transitional dentition, it may not be possible to ideally prepare the dental arches because of the presence of deciduous teeth. If early maxillary advancement is deemed necessary because of airway or psychosocial issues, the orthodontic alignment can be completed afterward. However, patients with a cleft who undergo early maxillary distraction are unlikely to undergo subsequent anterior maxillary growth and will often require finishing distraction or OGS at the time of facial maturity. Ideally, orthodontic alignment and arch coordination should be done before this procedure. The authors’ preference is to delay maxillary distraction in patients with a cleft until facial growth is completed.

Presurgical Planning

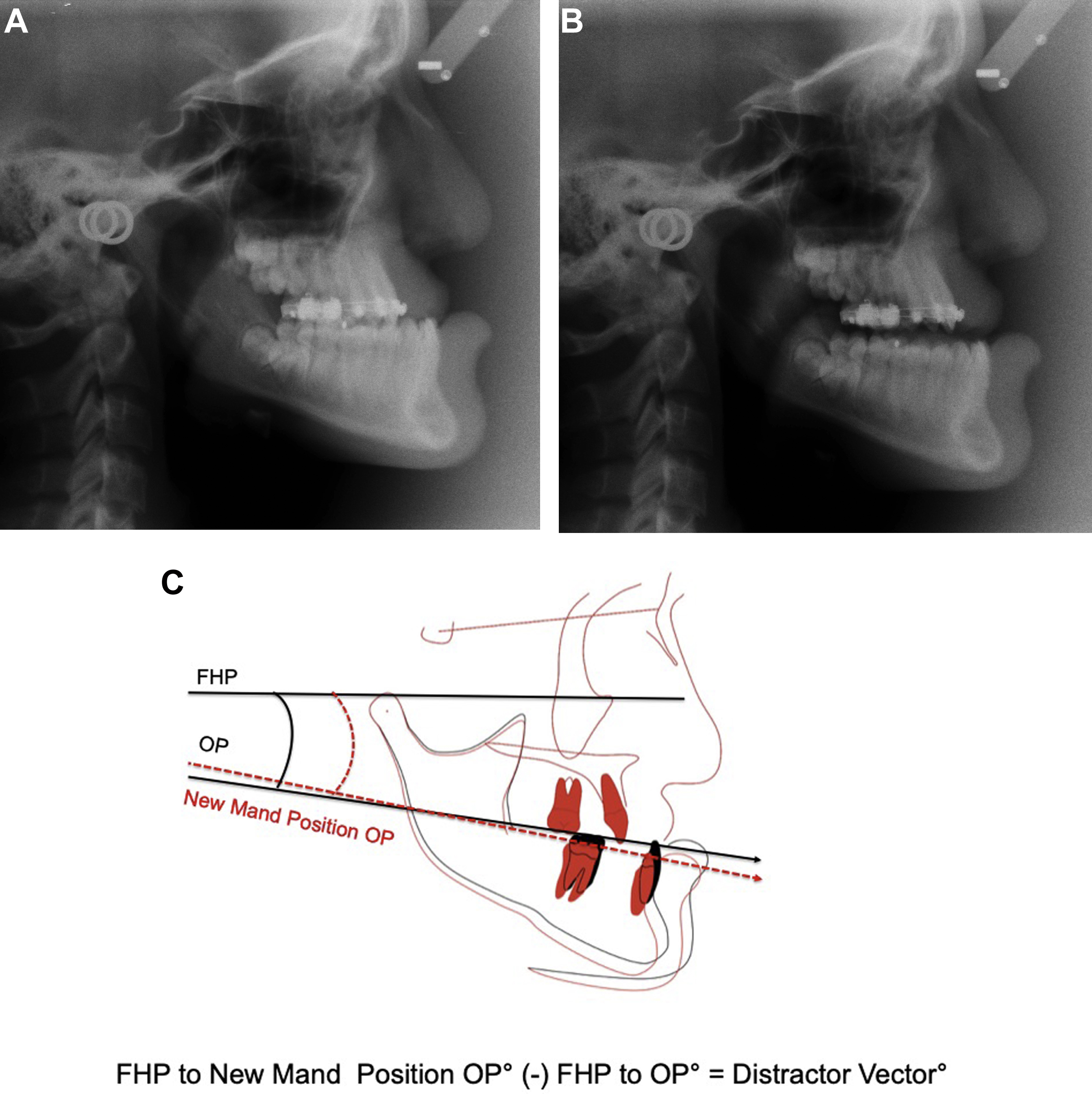

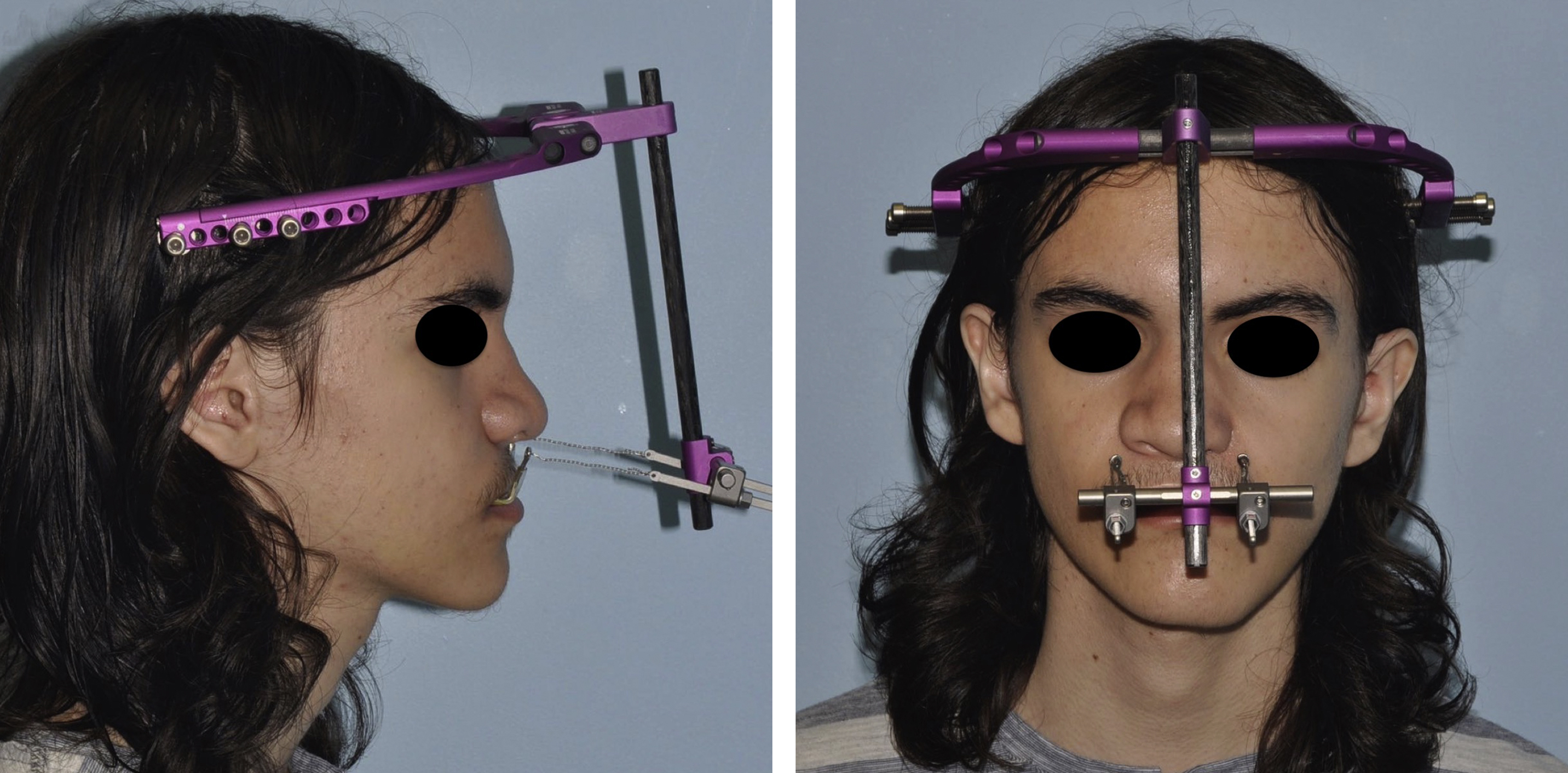

Thorough facial and intraoral examination with speech velopharyngeal evaluation is performed in all patients. Traditional cephalometry (with hand tracing), digital cephalometry, or 3-dimensional virtual surgical planning can be used. The planning radiograph or 3-dimensional scan is obtained with the lips in repose and the teeth in full occlusion. If the patient has vertical maxillary hypoplasia, the clinician should determine the degree of vertical overclosure, as a radiographic record taken in an overclosed position will disrupt accurate presurgical planning in several ways ( Fig. 1 A). First, the predicted maxillary advancement will be greater than what will be required. Second, the upper lip form will be abnormal in the study photographs and radiographs. Third, an incorrect mandibular occlusal plane measurement will be recorded, leading to an inappropriate maxillary distraction vector. If the patient exhibits overclosure, the radiographic record is taken with the mandible in rest position and the lips in repose. To assure accuracy of the mandibular position, a central relation registration bite is obtained and used while the necessary facial photographs and radiographs are taken ( Fig. 1 B). The radiographs are traced to determine the mandibular occlusal plane and the distraction vector of the maxilla. The maxillary occlusal plane is drawn and compared with the mandibular plane relative to Frankfort Horizontal Plane. The difference between the two is the desired vector ( Fig. 1 C). It is also critical to know the location of the approximate center of mass of the bone segment to be distracted. , In the sagittal plane, force vectors passing above, through, or below the center of mass will rotate the segment in a clockwise, straight, or counterclockwise direction respectively. In the maxilla, the approximate centers of mass and resistance are located above the mesial root of the first molar. The position of the eyelets on the external traction hooks is lateral to the alar cartilages bilaterally and at or above the level of the nasal aperture or palatal plane. It is important to record tooth shown in repose and the maxillary dental midline relative to the skeletal midline. If they are different, the distractor device needs to be differentially activated to correct the midline. When utilizing the HIMXD, the midline can be corrected at the time of device placement with fine adjustment in yaw position, then at the end of activation with differential final extension of the right and left devices. The RED and HIMXD systems allow for correction of the inferior pitch, as well as yaw. The RED system also has the capacity for a degree of roll correction. These adjustments are done by differentially activating the distraction screws, repositioning the horizontal distractor bar toward the right or left, then differentially altering the superior or inferior position of the distraction screws mounted on the horizontal bar combined with the use of interarch elastics ( Fig. 2 ).

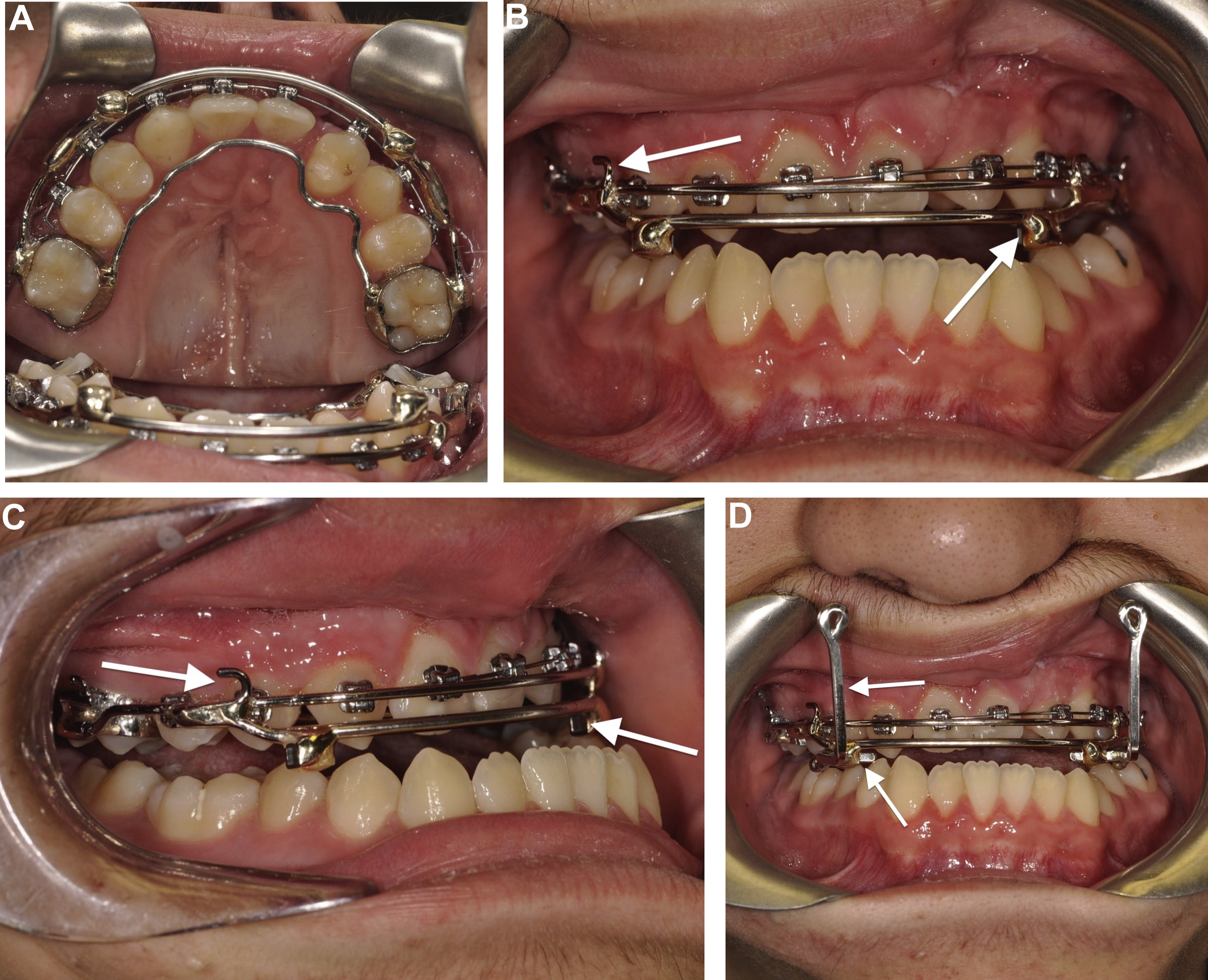

Intraoral Splint

For both external and internal distraction devices, the authors use 0.040″ stainless steel wire conformed to the labial and palatal aspects of the dental arch and soldered to the first molar bands ( Fig. 3 A–C). If desired, additional teeth can be incorporated for added retention of the appliance. In younger patients undergoing RED distraction, maxillary second primary molars can be used to support the splint if they have adequate root support and are stable. The RED splint has 2 square tubes just medial to the oral commissures that are used to secure 2 removable rectangular hooks, which connect the intraoral splint to distraction screws mounted onto the RED system. , The height of the traction hooks is such that they are level to or above the palatal plane for vector control (see Fig. 2 ; Fig. 3 D).