Chapter 33 FAT GRAFTING IN HIV-POSITIVE PATIENTS

The atrophic changes that occur in HIV-positive patients is an issue that most likely will disappear in decades to come as a result of advances in treatment, but for individuals affected today, the changes to the face and body are a visible and stigmatizing disorder that justify an interventional approach. Fat grafting, which has substantial longitudinal documentation of exceptional results as a filling material, provides an option for treatment of atrophic areas in these individuals. Because many HIV-positive patients do not have significant subcutaneous fat depots, some authors question whether the attendant atrophy of HIV can be resolved with the use of autologous fat grafting, given that patients can be treated with injection of synthetic materials. However, in patients with this chronic disease for which there is no expectation of spontaneous healing, the use of synthetic materials is unsuitable, because patients will demonstrate cyclical contour changes as the filler is resorbed. It is very expensive to treat atrophic areas beyond the face. Permanent materials such as silicone or methacrylate can be an option, but this kind of material tends to lead to more complications when high volumes are used, and these patients require high volumes, including in the face.

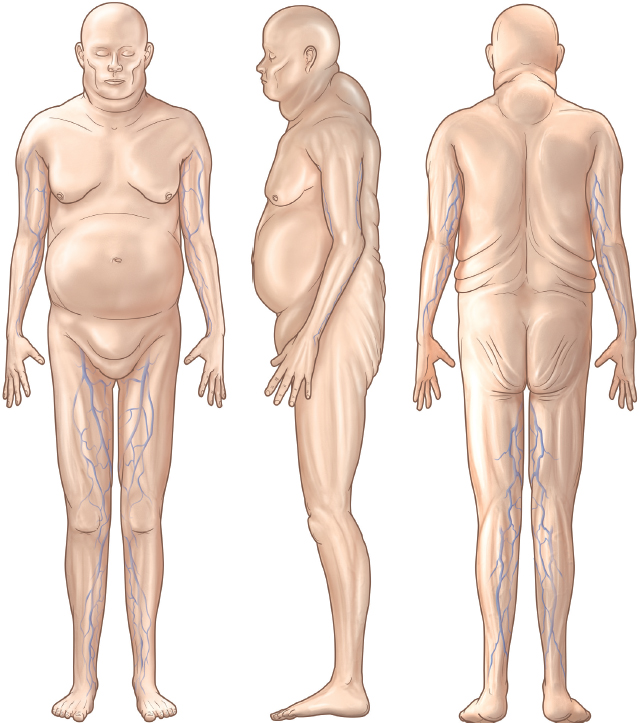

Abnormal changes in body fat distribution affecting HIV-positive patients were described in the late 1990s and were called HIV-associated lipodystrophy. 1 – 3 These changes include peripheral fat loss or lipoatrophy (LA), central fat accumulation or lipohypertrophy, or a combination of both of these types of changes in the same patient. The main clinical features are peripheral LA of the face, limbs, and buttocks and central lipodystrophy (LD) within the abdomen, breasts, neck, pubic region, and over the dorsocervical spine (“buffalo hump”), as well as subcutaneous lipomas and metabolic disturbance (insulin resistance, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertriglyceridemia). The prevalence has been described as being between 10% and 80%.

The pathogenesis of HIV LD is strongly related to the highly active antiretroviral therapy, which may increase the expression of other risk factors such as the individual’s genetic susceptibility, HIV clinical stage, race, sex, exercise level, age at the start of antiretroviral therapy, and many other factors. 4

The psychological impact, especially of facial atrophy (FA), can be devastating for many patients, leading them to fail to adhere to their antiretroviral treatment regimen. 5 , 6 They develop an altered body image and may become depressed and anxious that the visible changes will disclose to others that they are infected, and thus they experience social distress and isolation. 7 – 9 Sometimes patients state that they find it worse to live with LD than with HIV. 10 , 11

Earlier detection and treatment of HIV infection, as well as the use of antiretroviral drugs with less deleterious effects on body fat, make it reasonable to hypothesize that there will be a decrease in the prevalence of LD in HIV patients in the coming years. However, currently there is no specific treatment for established LD. LA can potentially be reversed by switching from antiretroviral drugs known for their adverse effects on adipose tissue to regimens that are less toxic in this regard, even though complete subcutaneous fat recovery cannot be expected. For this reason, it is necessary to establish a symptomatic treatment. 12 – 14

Material and Methods

AESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS

DISCLOSURE: Some data contained in this chapter have been made possible thanks to research grants provided by the Spanish Ministry of Health: Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria 03/0393, and Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria 08/0285.

Among all the features of LD, neck fat hypertrophy (buffalo hump) and LA are probably the most significant, because they are typical features of this syndrome and may lead to identifying the person as infected with HIV.

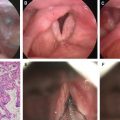

LA areas in the face comprise temple wasting, which makes the temporal fossa noticeable, and loss of subcutaneous fat from the cheeks showing an emaciated appearance (especially noticeable between the nose and the anterior rim of the masseter muscle and between the lower rim of malar bone to the mandible), prominent nasolabial folds, facial skeletonization (when the skin lies directly on bony and muscular facial structures), negative vector (concave cheek), and orbital hollowing. Other accompanying facial signs in the LD patient are submental fat accumulation and an increase in the parotid volume, which together with the FA confers a widened appearance to the face. LA can also be easily seen surrounding the zygomatic arch, but in this area it does not have the same repercussions for facial appearance as does atrophy in the cheeks.

Subcutaneous tissue in these patients is also depleted from the arms below the shoulders, buttocks, and lower limbs (peripheral wasting), with the distinctive prominence of the superficial veins in these sites, and the intermuscular grooves and bony prominences (femoral condyles) are especially noticeable. Patients complain of buttock flattening, not only because of the obvious aesthetic impairment, but also functional difficulty in holding up pants, shorts, or skirts, even when wearing a belt. Women used to be more worried than men about visible leg veins, because these are not common in healthy women; however, visible veins are common in healthy, lean, athletic men.

Because fat grafting can play an important role in modifying the stigmata of LD, surgeons should keep this in mind when discussing a liposuction procedure with such a patient. The fact that this fat could be useful for treating atrophic areas elsewhere in the body should be presented as an option in the first patient consultation.

ANATOMIC CHANGES AND CLASSIFICATIONS

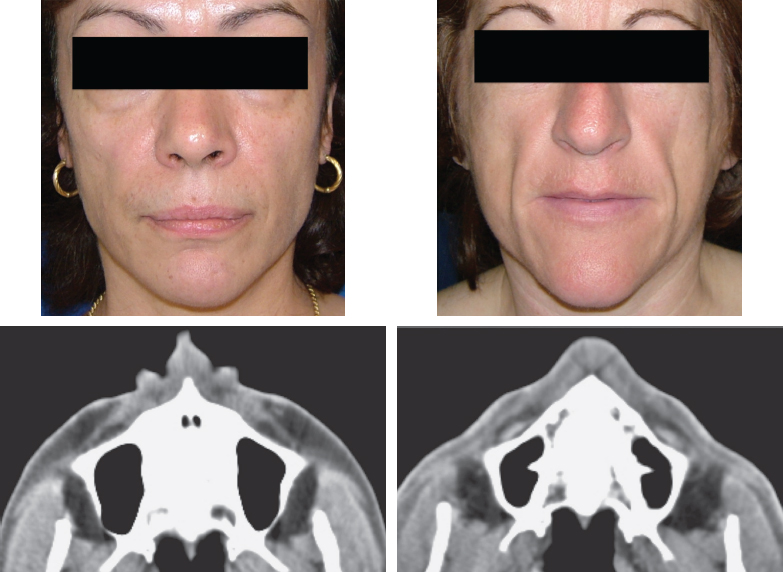

CT scans and MRIs have demonstrated thinning of the subcutaneous fat as well as an increase in density of this tissue. For this reason patients develop a sunken appearance in the anatomic areas where there is a lack of bony or muscular support, as in the cheeks, or between muscular compartments, such as in the thighs. However, contrary to what was believed when the first cases of HIV-related FA were diagnosed, the deep fatty bags in the face, such as the buccal fat pads, do not play a significant role in the physical appearance of FA, because they are not depleted. 15

The patient on the left has mild atrophy; subcutaneous fatty tissue is still present, as well as buccal fat pads. In the patient on the right, atrophy of the subcutaneous tissue is severe, but the buccal fat pads are still preserved.

Different methods have been described to clinically assess and classify the patients by the severity of their LD, but most proposed classifications are very subjective and only consider the face; they lack an objective method for categorizing all the features of LD in the body.

Quantitative measure of the subcutaneous fat has been performed using imaging methods (CT scans, MRIs, ultrasonography, DEXA), but none of these has been used to establish criteria for severity. For this reason the diagnosis of LD has been subjective, through the physician’s evaluation and the patient’s observations. 12

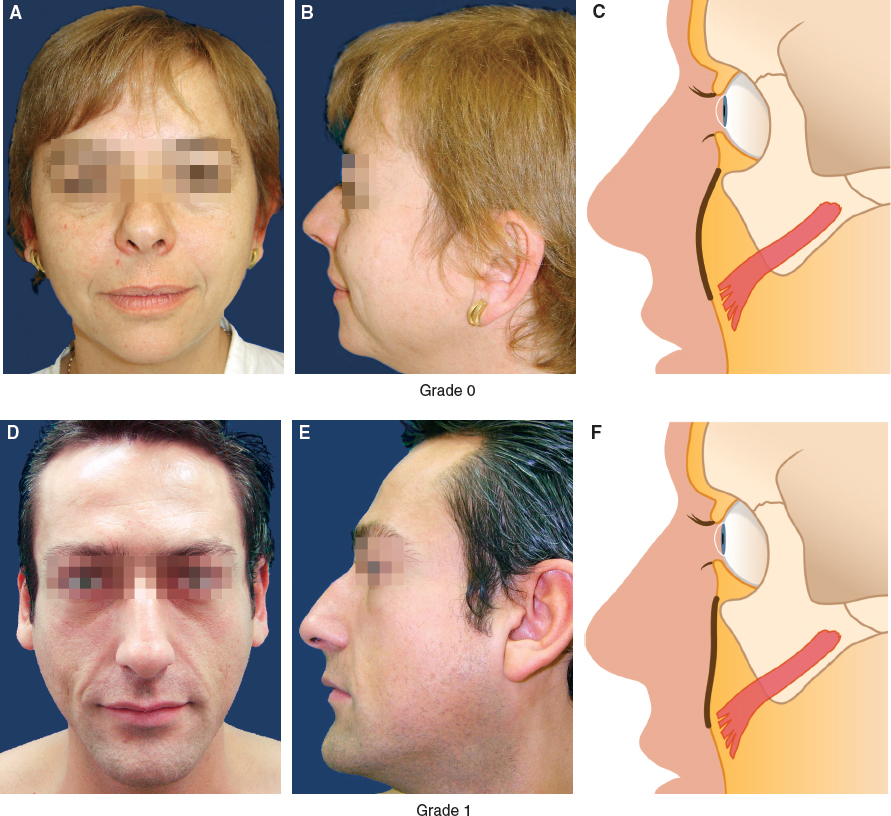

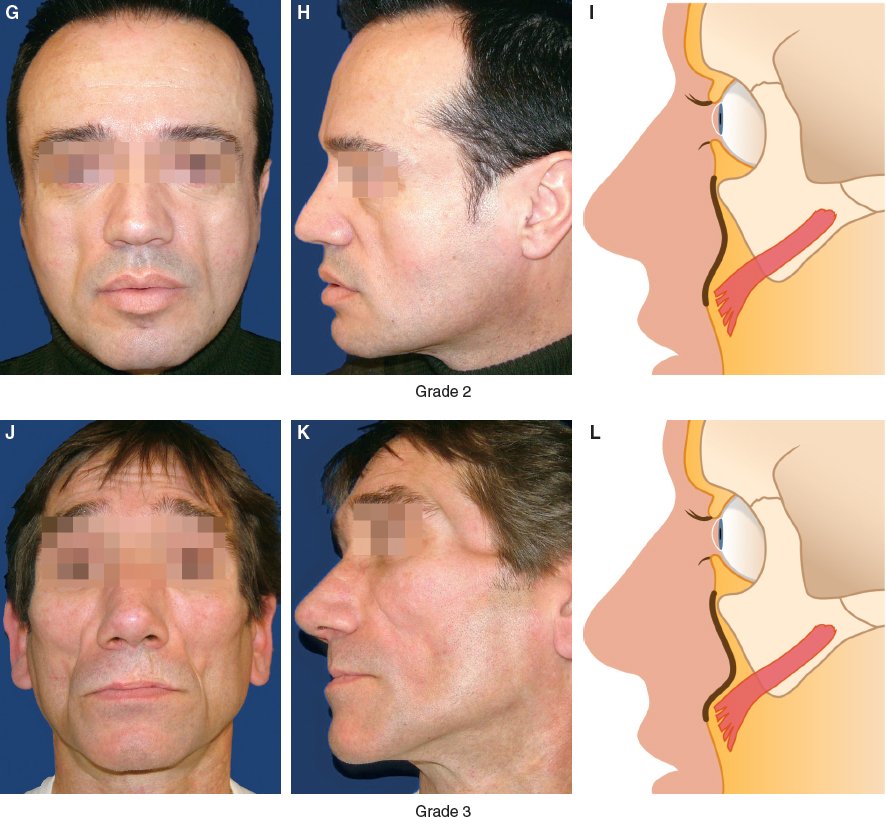

We recommend the following classification system because of its simplicity and ease of use for both FA and LD of the buttocks. To assess FA, a correlation is drawn with facial fat volumes measured by CT scan, 16 which classifies the patients in four degrees of atrophy. With no FA (grade 0), the cheekbone area has a convex contour from the orbital rim to the nasolabial fold. When there is a minor degree of atrophy (grade 1), the patient shows only a loss of this convexity, as well as some flattening of the malar eminence. These signs may also be seen in persons without HIV but who have facial skeleton dysmorphia.

Progression of FA (grade 2) is characterized by further shrinkage of the malar eminence, leading to a clinical impression of sunken skin under the malar lower rim. Patients classified as having the most severe degree of FA (grade 3) have easily identified prominence of the zygomatic major muscle and other superficial muscles of the face; the sunken areas extend from the lateral aspect of the upper lip to the lateral aspect of the malar bone, giving the face a skeletonized appearance.

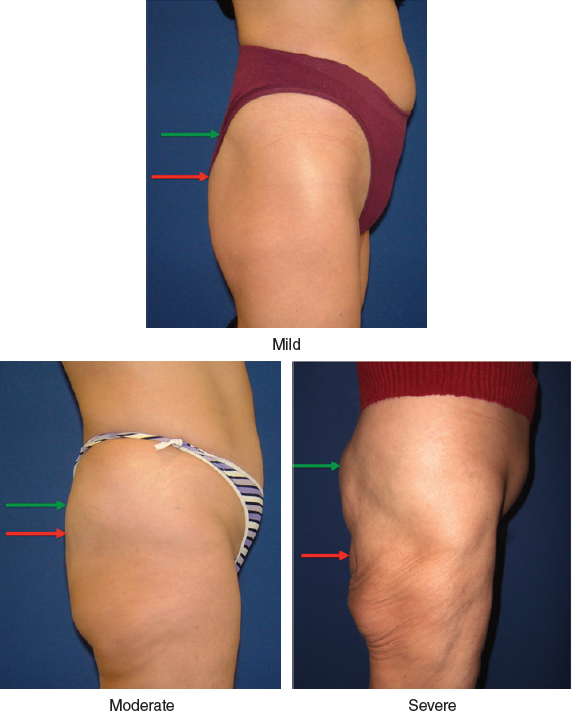

We have also published a clinical classification for assessing atrophy of the buttocks. 17 When the profile of the buttocks becomes flattened, but the contour still projects more than the sacrum, this is considered to be mild atrophy; when the projection of the buttocks is at the level of the sacrum, along with a slight ptosis, this is considered moderate atrophy; and when complete atrophy of the fat is present, along with skeletonization and the appearance of furrows in the bottom of the buttocks, this is considered severe atrophy.

A structured classification for lower and upper extremity LA is currently lacking, but it can be considered that when the veins of the lower limbs are readily discernable, this is the maximum degree of severity. This is the aspect that concerns patients most in regard to lipoatrophy of the limbs.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Symptomatic treatment of LA involves the transfer of autologous fat or injection of synthetic materials. The treatments most often used, especially for correction of FA, are fat grafting, polylactic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, and hyaluronic acid. 18 Other materials that have been used are silicone (United States), polyacrylamide (Europe), polyalkylimide gels (Europe, Mexico), and methacrylate (South America). Every suggested treatment presents advantages and drawbacks, and their results vary.

Fat grafting to the atrophied area seems to be the most valid option, because this method restores “like with like,” using the same kind of tissue that the disease has caused to atrophy. 19 , 20 Other advantages are that grafted fat is autologous, permanent, biocompatible, nontoxic, and has physical features like those of the tissue it restores. For these reasons our discussion will focus on fat grafting for the correction of LA.

Although the durability of fat grafts in HIV-affected patients has been a topic of discussion, our experience, and that of others who have used this technique, is that there is little resorption of properly grafted fat, 19 – 21 and it tends to behave like the tissue of the area from which it was harvested. This is an advantage, because LA is chronic in HIV-positive patients, and even administration of the newer antiretroviral drugs does not improve the patient’s condition enough to achieve full restoration of the patient’s features.

The cost of fat grafting can ultimately be less than that when synthetic fillers are injected, because although fat injection requires more material and time, the large amounts of exogenous filler required in these patients increases the price of the treatment, and the results with synthetic fillers are temporary, compared to that with fat grafting.

Fat grafting is indicated as the first option in HIV patients with LA when lipoaspirate can be obtained from any area of the body, often from the areas where these patients experience lipohypertrophy, such as the buffalo hump, infraumbilical area, pubis, back rolls, and male breasts. When a patient’s face has more severe FA, fat grafting is the optimal choice of treatment, because a large amount of filler will be necessary, and it must be durable. In these patients, a reabsorbable filler material will fail to provide good volumetric correction over time, which will give the patient an oscillating appearance, with periods in which the face appears full, alternating with periods of leanness. Furthermore, synthetic materials in large amounts are more likely to present complications such as infection, granuloma, nodulation, and an unnatural appearance. It has been possible to find a source of subcutaneous fat to treat FA in more than 50% of our patients. Correction of atrophy of the buttocks and limbs can be difficult in many HIV-positive patients, because these areas require a huge volume of fat, as much as tenfold or more than is needed to treat the face.

It is best to perform a fat grafting procedure when the patient’s HIV LD has stabilized so that the surgeon can work with stable adipose tissue compartments, both in the donor and recipient sites. This helps to avoid unexpected changes in fat volume associated with the evolution of the disease, although it does not alter the fat injection technique used.

A contraindication to fat grafting in these patients is previous implantation of synthetic injectables. These individuals must be rejected for fat grafting, because the synthetic material of these injectables can be contaminated, and this can lead to an infection or can induce granuloma or nodulation. The residual synthetic material can also interfere with the take of fat grafts. Patients must be asked during history-taking to specify which material was used and when it was injected. If it was a reabsorbable material, the patient is advised to wait for fat grafting until all of the synthetic material has been absorbed, usually 1 year after the injection, and its presence can be assessed by ultrasonography if necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree