Abstract

Benign cutaneous pigmented lesions may result from an increased production of melanin or a proliferation of melanocytes. In ephelides, café-au-lait macules (CALMs), Becker melanosis, and lentigines, there is an increase in melanin production by melanocytes followed by its transfer to keratinocytes. When multiple CALMs are present, the possibility of a neurocutaneous syndrome, most commonly neurofibromatosis type 1, needs to be considered whereas generalized lentiginosis may point to the diagnosis of Carney complex or Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines (LEOPARD syndrome).

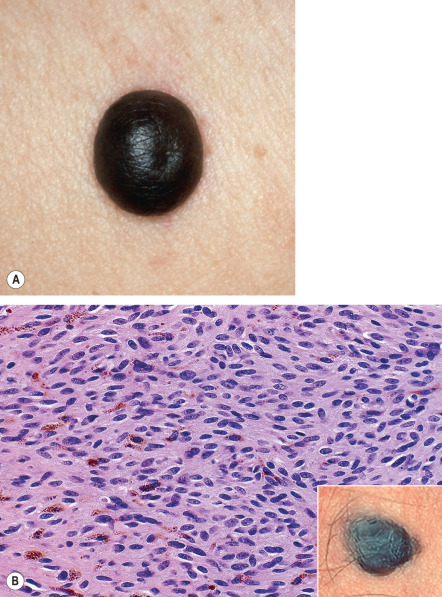

Dermal melanocytosis is characterized by blue to blue–gray skin discoloration and includes the entities Mongolian spot, nevus of Ota, and nevus of Ito. Histopathologically, a sparse number of dendritic, melanin-producing melanocytes are scattered among the collagen bundles of the reticular dermis. Blue nevi represent dermal melanocytomas and present as blue–gray to blue–black, firm papules, nodules or plaques. Histopathologically, common blue nevi are characterized by aggregates of dendritic, heavily pigmented melanocytes within a variably sclerotic dermis. In cellular blue nevi, there may be nodules of non-pigmented dermal melanocytes admixed with melanophages within the dermis and subcutis.

Common acquired melanocytic nevi are classified as: (1) junctional, with a proliferation of melanocytes at the dermal–epidermal junction; (2) intradermal, with nests of melanocytes within the dermis; and (3) compound nevi, with both intraepidermal and intradermal complexes of melanocytes. Based upon clinicopathologic features, there are several other variants of melanocytic nevi, including Spitz nevi, atypical (dysplastic) nevi, acral nevi, halo nevi, combined nevi, recurrent nevi, and speckled lentiginous nevi. Distinguishing Spitz nevus and its variants from cutaneous melanoma can be one of the most challenging problems in dermatopathology. Atypical nevi may arise in a sporadic fashion or be inherited in the context of familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome.

Congenital melanocytic nevi are melanocytic nevi that are usually present at birth but sometimes appear during infancy (tardive congenital nevi). They are classified as small, medium-sized, large, and giant. Associated neurocutaneous melanosis is seen in patients with multiple medium-sized congenital nevi or a large/giant congenital nevus while melanoma occurs primarily in those with the latter. In contrast to common acquired nevi, the melanocytes of congenital nevi may infiltrate the lower reticular dermis, subcutaneous fat, fascia, and even deeper structures.

Keywords

café-au-lait macule, Becker melanosis, Becker nevus, melanocytic nevus, nevomelanocytes, nevocellular nevus, nevus cells, lentigo, lentigo simplex, atypical nevus, dysplastic nevus, blue nevus, Spitz nevus, spindle and epithelioid cell nevus, congenital nevus, congenital melanocytic nevus, compound nevus, junctional nevus, intradermal nevus, pigmented spindle cell nevus, mucosal melanotic macule, labial melanotic macule, dermal melanocytosis, nevus of Ota, acral nevus, nevus spilus, speckled lentiginous nevus, halo nevus, combined nevus, recurrent nevus, common blue nevus, cellular blue nevus

Ephelides

▪ Freckles

- ▪

Small, well-circumscribed, pigmented macules found only on sun-exposed skin of individuals with fair skin

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Ephelides are common in individuals with blond or red hair . They are not present at birth, but usually begin to appear during the first 3 years of life. The hyperpigmentation in ephelides is the result of increased sun-induced melanogenesis and transport of an increased number of fully melanized melanosomes from melanocytes to keratinocytes. Variants of the gene that encodes the melanocortin-1 receptor play a role in the development of red hair and ephelides (see Ch. 65 ) .

Clinical Features

Ephelides only occur on sun-exposed areas of the body, in particular the face, dorsal aspects of the arms, and upper trunk. They do not occur on mucous membranes. Ephelides are well demarcated and are round, oval, or irregular in shape. They are usually 1 to 3 mm in diameter, but are occasionally larger. Depending on the intensity of sun exposure, ephelides vary in color from light to dark brown, but almost never become as dark as lentigines or junctional nevi. They may increase in number and distribution and show a tendency for confluence, but can also fade over time with aging.

Ephelides are benign and show no propensity for malignant transformation . While they are not a direct precursor of melanoma, ephelides are a marker of ultraviolet (UV)-induced damage and, hence, a marker for an increased risk of UV-induced neoplasia . In a study of 195 patients diagnosed with melanoma in England, the density of freckles on the face and arms was found to be more strongly associated with cutaneous melanoma than the number of melanocytic nevi. When adjusted for other factors (nevi, sunburns, skin type), those with a high freckle density had an odds ratio of 6.0 for developing melanoma compared with those without freckles. Some ephelides may represent a subtype of solar lentigo .

Pathology

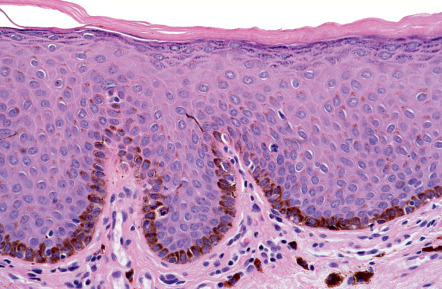

The epidermis exhibits a normal configuration. The keratinocytes show an increase in melanin content, predominantly in the basal cell layer . Occasionally, melanophages are seen in the papillary dermis. The density of melanocytes within ephelides does not differ significantly from normal. Compared to adjacent uninvolved epidermis, the melanocytes in ephelides are larger and have more branching of dendrites and a higher DOPA positivity, apparently indicating greater functional activity.

Differential Diagnosis

Ephelides must be distinguished from simple lentigines, solar lentigines, small café-au-lait macules, and junctional nevi. In general, ephelides are lighter in color than simple lentigines, are confined to sun-exposed skin, and are responsive to solar exposure. In contrast, simple lentigines may occur on any site and are persistent. Table 112.1 compares ephelides and solar lentigines. Café-au-lait macules are usually solitary and larger than ephelides.

| COMPARATIVE CLINICAL FEATURES OF EPHELIDES AND SOLAR LENTIGINES | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ephelides (freckles) | Solar lentigines (see Ch. 109 ) | |

| Epidemiology | ||

| Age of appearance | Early childhood | By 20–30 years (I, II) |

| Skin color | Light pigmentation | Light to dark pigmentation |

| Hair color | Often red or blond hair | Any type |

| Skin phototype | More common in I, II | More common in I and II, but also in III and IV |

| History | ||

| Precipitating factors | Bursts of high-intensity sun exposure activate latent predetermined melanocytes, leading to permanent freckles | Repeated sun exposure over time alters melanocytes within a circumscribed area to overproduce melanin |

| Duration of lesions | Fade without sun exposure | Persist for life |

| Relation to season | Much darker in summer, fade in winter and over time with aging | May darken in summer but do not fade in winter |

| Heredity | Probably AD; also AR when related to MC1R variants | No data |

| Physical examination | ||

| Type of lesion | Macule | Macule |

| Size | 1–5 mm | 5–15 mm or larger |

| Color | Light or medium brown | Medium or dark brown |

| Shape | Oval to irregular | Oval to irregular |

| Border | Smooth to jagged | Smooth to jagged |

| Distribution | Favor the face, extensor forearms, and back; rare on the dorsal aspect of the hands | Sites of chronic sun exposure, especially the face, arms (including dorsal aspect of the hands), and upper trunk |

| Dermoscopic features | ||

| Uniform pigmentation and a moth-eaten edge | Diffuse light brown structureless areas, sharply demarcated and/or moth-eaten borders, fingerprinting, and a reticular pattern with thin lines that are occasionally short and interrupted | |

Treatment

Since darkening of ephelides depends on UV radiation, sun exposure should be minimized and use of sunscreens, hats, and protective clothing recommended. Although topical retinoids and hydroquinone may lighten lesions, it is difficult to achieve an even clinical effect. Pigment-specific lasers and cryotherapy represent additional treatment options. Of note, any resulting dyspigmentation from these destructive therapies can be more disturbing to the patient than the original lesion.

Café-Au-Lait Macules

- ▪

Well-circumscribed, uniformly light to dark brown macules or patches that often range from 2 to 5 cm (in adults)

- ▪

Usually noted during infancy or early childhood

- ▪

Found in 10–20% of the normal population but can serve as a marker of an underlying genodermatosis, especially when multiple

Epidemiology

In an individual, the number of café-au-lait macules (CALMs) can vary from one to more than a dozen. When multiple, the possibility of a genetic syndrome, such as neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), needs to be considered (see Table 61.4 ). Single CALMs are found in 10% to 20% of the normal population, and up to 1% of healthy children have up to three CALMs, especially African-American children. The lesions may be present at birth, but usually become clinically obvious during the first year of life and then increase proportionately in size with age.

Pathogenesis

The hyperpigmentation observed in CALMs is due to increased melanogenesis and an increased melanin content within keratinocytes. While the underlying pathogenesis has not been elucidated in patients with isolated lesions, biallelic NF1 inactivation has been identified in melanocytes from CALMs in patients with NF1, and in McCune–Albright syndrome, affected skin contains an activating mutation in the gene that encodes G s α (see Chs 61 & 65).

Clinical Features

The term café-au-lait refers to the lesion’s characteristic homogeneous color reminiscent of coffee with milk. They can vary from light to dark brown, depending upon the patient’s level of constitutive pigmentation. CALMs are completely macular, and they often have an overall oval morphology with margins that are well defined and regular (“typical” CALMs; Fig. 112.1A ) . They may be located anywhere on the body, with the exception of the mucous membranes. CALMs are usually 2–5 cm in diameter in adults, but may vary from freckle-like lesions (≤2 mm) to patches that are >20 cm in diameter ( Fig. 112.1B ). CALMs enlarge proportionately with overall body growth and then remain stable in size during adulthood. By dermoscopy, a homogenous brown patch is seen with perifollicular hypopigmentation; a faint reticular pattern may also be present.

Compared with NF1, the CALMs of McCune–Albright syndrome are typically fewer in number, larger, and have a midline demarcation; they usually have a segmental distribution pattern or present as broad bands along the lines of Blaschko . These CALMs favor the head, neck, trunk and buttocks. They also tend to be unilateral, often involving the same side as the bone lesions and situated in proximity. They can, however, be indistinguishable both clinically and histologically from the CALMs of neurofibromatosis. If present, superimposed lentigines (due to widespread “freckling” extending beyond the axillae) can point to NF1-associated CALMs.

Pathology

Light microscopy shows a normally configured epidermis with a slightly increased melanin content in the basilar keratinocytes. The adnexal epithelium is spared of hyperpigmentation, and melanophages are rarely found in the dermis. In DOPA-stained epidermis from most patients with neurofibromatosis, the density of melanocytes is higher in both CALMs and normal adjacent skin, in comparison with healthy individuals. The melanocytic density in isolated CALMs of otherwise normal persons, however, is usually less than in surrounding skin. Melanin macroglobules (large pigment particles resulting from fusion of autophagosomes containing varying numbers of melanosomes) may be found in CALMs, but they are not specific for neurofibromatosis, as they are occasionally found in isolated CALMs (without any underlying disease) and occur in several other conditions such as simple lentigines, Becker melanosis, congenital melanocytic nevi, and sometimes even normal skin. By electron microscopy, the melanosomes are usually dispersed singly within melanocytes and are usually homogeneous, electron-dense, and ellipsoidal when fully melanized .

Differential Diagnosis

Hyperpigmented macules or patches that might be confused with CALMs include pigmentary mosaicism (segmental pigmentation disorder, linear nevoid hyperpigmentation), early nevus spilus (before the “speckles” have appeared), Becker melanosis (without obvious hypertrichosis), mastocytoma, mosaic (segmental) neurofibromatosis, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Smaller lesions may resemble lentigines or acquired melanocytic nevi, while larger lesions may be confused with relatively flat congenital melanocytic nevi. Café-noir spots are hyperpigmented patches that have an even darker hue (relative to background skin) than CALMs and are seen in LEOPARD syndrome (Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines) and the Carney complex.

Treatment

CALMs have never been reported to undergo malignant change. Topical agents (e.g. hydroquinone) and sun protection will have no effect on CALMs. A variety of lasers have been used to treat CALMs, with variable success . The risks of laser surgery include transient hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, slight scarring, permanent hyperpigmentation, incomplete clearance, and especially recurrence. Typically, between 1 and 14 treatments are required, and responses are difficult to predict. For instance, of 12 CALMs treated with a Q-switched ruby laser in one study, 50% developed repigmentation within 6 months. Responses to frequency-doubled Nd:YAG are also quite variable.

Becker Melanosis (Nevus)

▪ Becker’s nevus ▪ Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma ▪ Nevoid melanosis

- ▪

Unilateral, hyperpigmented, often hypertrichotic patch or slightly elevated plaque

- ▪

Most commonly on the shoulder of male patients

- ▪

Onset usually during adolescence

Epidemiology

Becker melanosis has been observed in all races . Although it is usually acquired, some cases are congenital. The lesions most often appear during the second and third decades of life and are six times more common in males than in females. Familial occurrence has been reported. In one study, the prevalence among 19 302 army recruits ages 17 to 26 years was 0.5%.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of Becker melanosis remains unclear. It is believed to be an organoid hamartoma of ectodermally and mesodermally derived tissues. An increase in androgen receptors and probable heightened sensitivity to androgens have been postulated. The latter characteristics would explain its onset during or after puberty, as well as its clinical and histologic manifestations, which include hypertrichosis, dermal thickening, acne, and hypertrophic sebaceous glands. Androgen stimulation could also explain the accentuated smooth muscle elements often found in the dermis of Becker melanosis . Recently, postzygotic mutations in beta-actin were reported to be associated with Becker nevus and Becker nevus syndrome (see below) .

Clinical Features

The onset of Becker melanosis is usually noted during the second or third decade of life, sometimes following intense sun exposure. Lesions are most often unilateral and usually involve an upper quadrant of the anterior or posterior chest ( Fig. 112.2A,B ). However, they have also been described on the face, neck, lower trunk, extremities, and buttocks ( Fig. 112.2C ) . Normally, Becker melanosis appears as a single lesion, but multiple lesions have occasionally been observed. The diameter ranges from a few centimeters to >15 cm, and the most common configuration is block-like, although linear patterns have been reported.

The hyperpigmentation varies from uniformly tan to dark brown and while the lesions are well demarcated, the margins are usually irregular. The center of the lesion may show slight thickening and corrugation of the skin. Hypertrichosis usually develops after the hyperpigmentation, and the hairs become coarser and darker with time (see Fig. 112.2B ). Sometimes, the hypertrichosis is subtle and can only be appreciated by comparison with the contralateral side. The hypertrichosis and pigmentation may not overlap completely. After its initial appearance, Becker melanosis may enlarge slowly for a year or two but then remains stable in size. The color can fade with time, but hypertrichosis usually persists.

Normally, Becker melanosis is asymptomatic, but some patients report pruritus. Firmness to palpation may point to an associated smooth muscle hamartoma. In some patients, perifollicular papules may be a sign of coexistent proliferation of the arrector pili muscle. Acneiform lesions strictly limited to the area of hyperpigmentation have also been reported.

Becker melanosis is a benign lesion, and malignant transformation has not been reported. In contrast to the hyperplasia of the ectodermal and mesodermal tissues in Becker melanosis, developmental anomalies that are generally hypoplastic in nature have occasionally been associated with Becker melanosis. These abnormalities include hypoplasia of the ipsilateral breast, areola, nipple and arm, ipsilateral arm shortening, lumbar spina bifida, thoracic scoliosis and pectus carinatum, as well as enlargement of the ipsilateral foot. Accessory scrotum and supernumerary nipples have also been reported. In cases of Becker melanosis with associated abnormalities (also referred to as “Becker nevus syndrome”), the male : female ratio is reversed at 2 : 5 (in comparison to 6 : 1 in those without abnormalities) .

Pathology

There is variable degree of acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and sometimes mild papillomatosis . Regular elongation of the rete ridges and hyperplasia of the pilosebaceous unit may be observed. The melanin content of the keratinocytes is increased, whereas the number of melanocytes is normal or only slightly increased, without nesting. Melanophages may be found in the papillary dermis. A concomitant smooth muscle hamartoma is often, but not invariably, present in the dermis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis primarily includes CALM, congenital melanocytic nevus, plexiform neurofibroma, and congenital smooth muscle hamartoma. The latter tends to be smaller in size, but some authors consider Becker melanosis and congenital smooth muscle hamartoma to be two ends of a clinical spectrum (see Ch. 117 ). A congenital melanocytic nevus, plexiform neurofibroma, and congenital smooth muscle hamartoma can all have cutaneous hyperpigmentation plus hypertrichosis. By dermoscopy, Becker melanosis is less likely to have focal thickening of network lines, globules or homogeneous diffuse pigmentation, when compared to congenital nevi. The presence of multiple CALMs and axillary freckling can be helpful in establishing the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis, and unlike Becker melanosis, CALMs do not have corrugation on side-lighting. In an occasional patient, histologic evaluation is required to confirm the diagnosis, especially if the lesion is in an unusual location and there is an associated smooth muscle hamartoma.

Treatment

Patients with Becker melanosis should be examined for possible soft tissue and bony abnormalities (see above). Electrolysis, waxing, camouflage makeup, and laser treatments may be recommended. The hyperpigmented component may respond to Q-switched ruby and frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser therapy , but recurrence rates are high. The hypertrichosis can be addressed, sometimes more successfully, with one of several lasers designed for this purpose (see Ch. 137 ).

Solar Lentigines

▪ Lentigo senilis ▪ Liver spot ▪ Old age spot ▪ Senile freckle

- ▪

Tan to dark brown or black macules due to exposure to UV radiation

Lentigo Simplex and Mucosal Melanotic Lesions

- ▪

Lentigo simplex: • simple lentigo • lentiginosis (if multiple)

- ▪

Mucosal melanotic lesions: • mucosal melanotic macules • lentiginosis • melanosis

- ▪

Anatomic subtypes: • oral melanotic macules • labial melanotic macules • genital lentiginosis • anogenital lentiginosis

- ▪

A lentigo simplex is a brown macule with an early age of onset (as compared with a solar lentigo) and little or no relationship to sun exposure

Epidemiology

The frequency of lentigo simplex in children and adults is unknown. Lentigines are found in all races and appear to occur equally in both sexes. Isolated lesions may be present at birth, more commonly in darkly pigmented than lightly pigmented newborns. These lentigines may increase in number during childhood or puberty. Sometimes they occur in an eruptive form called lentiginosis, with or without obvious precipitating factors. After melanocyte activation, lentigo simplex represents the next most common histology in matrix biopsies of longitudinal melanonychia (see Ch. 71 ). In darkly pigmented individuals, lentigo simplex is the most common histologic pattern for cutaneous pigmented lesions in acral sites.

Oral melanotic macules are found primarily in adults over 40 years of age. Some authors report a slight female predilection, whereas others describe both sexes being affected equally. The most common sites are the vermilion border, followed by the gingiva, the buccal mucosa and the palate. Up to 30% of melanomas in the oral cavity of Caucasians are preceded by melanosis for several months or years. In Japanese patients, two-thirds of infiltrative oral melanomas arise in association with oral melanosis. The labial (lip) melanotic macule usually appears between the second and fourth decades of life and has a strong predilection for Caucasian women.

The incidence of lentiginosis or melanosis of the female genital area is probably higher than reported. For example, 15% of 106 females between the ages of 16 and 42 years had genital “nevi”, and in a study of 100 random autopsies, three cases showed melanosis of the genitalia, and all three were elderly women. Most lesions are found on the labia minora, but they can also occur on the labia majora, the vaginal introitus, the cervix, the periurethral area, and the perineum as well as perianally. In general, lentiginosis and melanosis of the female genitalia are benign conditions; atypia is uncommon and progression to melanoma has rarely been observed .

In a study of 10 000 men between 17 and 25 years of age, 14% were noted to have “pigmented nevi” of the genitalia . It is uncertain what proportion represented penile lentiginosis or melanosis since no clinical descriptions or histologic studies were reported. In the literature, the ages of patients with penile lentiginosis or melanosis range from 15 to 75 years. The lesions occur on both the glans penis and penile shaft. Men can also develop lentigines perianally.

The incidence of conjunctival melanosis is unknown, but it can be assumed that primary acquired melanosis is a precursor lesion of melanoma in this area, since a significant number of conjunctival melanomas are associated with it. Lentigo simplex occasionally develops within scars following excision of cutaneous melanoma as do pigmented streaks due to basilar hyperpigmentation; the latter favors individuals with numerous solar lentigines.

Pathogenesis

An increased number of melanocytes within the basal layer of the epidermis leads to an increased production of melanin, resulting in hyperpigmented macules. To date, insights into lentigo formation have not been forthcoming despite the discovery of the genetic bases of several syndromes associated with lentiginosis (see Ch. 55 ). Some penile lesions have been reported to follow injury, irritation, or PUVA therapy; in women, hormonal factors are thought to play a role. Acral lentigines may be influenced by genetic factors, since they are frequently found in darkly pigmented individuals.

Clinical Features

Lentigines simplex are light brown to black, homogeneously pigmented macules occurring anywhere on the body, including mucous membranes and palmoplantar skin, without any predilection for sun-exposed areas. They are well circumscribed, round or oval, have regular borders, and are usually <5 mm (often <3 mm) in diameter. Lesions on the mucous membranes frequently have irregular, ill-defined borders as well as mottled non-homogeneous pigmentation with areas devoid of pigment ( Fig. 112.4 ). The latter may be several centimeters in diameter and may resemble early melanoma clinically. By dermoscopy, mucosal lentigines have a fingerprint pattern with narrow parallel lines and broader track-like pigmentation interrupted by dots and globules.

Lentigines simplex occur as solitary or multiple lesions. Generalized lentigines may be an isolated phenomenon without an underlying disease, either present at birth or appearing during childhood or adulthood, or it may be a sign of a genetic disorder ( Table 112.2 ).

| DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH MULTIPLE LENTIGINES | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disorder | Comments | Disorder | Comments |

| Generalized | Localized | ||

| LEOPARD syndrome (now referred to as Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines) |

| Head and neck (including oral mucosa) ± acral | |

| Peutz–Jeghers syndrome | |||

| Generalized lentigines |

| Bandler syndrome * |

|

| Deafness plus lentiginosis * |

| ||

| Carney complex (NAME/LAMB syndrome) |

| Laugier–Hunziker syndrome |

|

| Hyperkeratosis- hyperpigmentation (Cantú) syndrome |

| ||

| Arterial dissection plus lentiginosis |

| Cowden disease |

|

| Gastrocutaneous syndrome * |

| Centrofacial lentiginosis (neurodysraphic) |

|

| Tay syndrome * |

| ||

| Pipkin syndrome * |

| Inherited patterned lentiginosis |

|

| Cronkhite–Canada syndrome |

| ||

| Genital | |||

| Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome |

| ||

| “Photodistribution” | |||

| Xeroderma pigmentosum |

| ||

| Segmental | |||

| Partial unilateral lentiginosis |

| ||

* To date, observed in a single family

In contrast to lentigo simplex occurring on the skin, lesions on mucous membranes can slowly increase in size over months to years, with or without changes in the degree of pigmentation. The relationship between acral or anogenital lentigines and acrolentiginous melanoma requires more investigation.

Special forms and associated syndromes

Multiple lentigines may or may not be associated with other systemic manifestations. In LEOPARD syndrome (now referred to as Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines), the acronym refers to: l entigines, e lectrocardiographic conduction defects, o cular hypertelorism, p ulmonary stenosis, a bnormalities of genitalia, r etardation of growth, and d eafness (see Table 112.2 ). Multiple lentigines are present at birth or appear during early infancy and may increase in number during childhood. The lesions are generalized, occurring in both sun-exposed and sun-protected sites, including genitalia, palms, and soles.

The Carney complex is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by multiple lentigines and multiple neoplasias, including: myxomas of the skin, heart (atrial), and breast; psammomatous melanotic schwannomas; epithelioid blue nevi of skin and mucosae; growth hormone-producing pituitary adenomas; and testicular Sertoli cell tumors. Components of the Carney complex have been described previously as the NAME (n evi, a trial myxoma, m yxoid neurofibroma, e phelides) and LAMB ( l entigines, a trial myxoma, m ucocutaneous myxoma, b lue nevi) syndromes.

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is also an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by mucocutaneous lentigines which are present at birth or appear during childhood in combination with intestinal polyposis. The skin lesions have an acrofacial distribution pattern and favor the perioral region. Mucosal lesions may affect the palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, and conjunctivae. The major entity in the differential diagnosis is Laugier–Hunziker syndrome in which there are acromucosal lentigines and longitudinal melanonychia, but no consistent internal manifestations ( Fig. 112.5 ).

In partial unilateral lentiginosis , also referred to as segmental lentiginosis, there is unilateral clustering of lentigines, suggesting a developmental abnormality of melanocytes. The onset is often during childhood and the individual lentigines are well circumscribed, varying from 2 to 10 mm in diameter. There is no background hyperpigmentation (as in nevus spilus) and the lesion can expand in a wavefront-like manner. Patients with facial lesions may have ocular involvement and CALMs may also be present. Partial unilateral lentiginosis may be associated with mosaic (segmental) NF1.

Pathology

Lentigo simplex exhibits increased numbers of melanocytes in the basal layer of elongated epidermal rete ridges. Increased melanin in the basal layer and sometimes even in the upper layers of the epidermis and stratum corneum is commonly observed. Melanophages and a mild inflammatory infiltrate are often present in the superficial dermis.

Lesions on mucous membranes, including the lips, show acanthosis with or without elongation of the rete ridges ( Fig. 112.6 ). Slight melanocytic hyperplasia is usually observed, but may be absent. Hyperkeratosis, telangiectasia, activated fibroblasts, and large dendritic melanocytes have been described in labial melanotic macules. Some acral and mucosal lesions have been reported to exhibit cytologic atypia of the melanocytes. Ultrastructurally, melanin macroglobules have been observed within the melanocytes, as well as in keratinocytes and melanophages. These are not specific for lentigo simplex, since they have been described in other pigmented lesions (see above).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a solitary lentigo simplex consists primarily of a junctional melanocytic nevus, a relatively flat form of compound melanocytic nevus, solar lentigo, and ephelis. In some instances, cutaneous melanoma, pigmented spindle cell nevus, and cutaneous intracorneal hemorrhage might enter into the differential diagnosis.

Although there is a continuum from simple lentigo to junctional melanocytic nevus, the simple lentigo is distinguished from melanocytic nevi by the absence of distorted skin markings when viewed with side-lighting, and a lentigo simplex is often smaller than a melanocytic nevus. That said, histopathologic examination may be required for discrimination as melanocytic nests are not found in lentigo simplex. Lentigo simplex is usually distinguished from a solar lentigo by its smaller size, symmetry, uniform pigmentation, and lack of relationship to sun-exposed sites. However, this clinical distinction may not be possible in some instances.

Treatment

In general, there is no need to treat a benign-appearing lentigo simplex. Lesions on acral or mucous membranes should be evaluated carefully and, if clinically atypical, should be considered for biopsy to assess for melanocytic atypia. Patients with both generalized and localized lentiginosis should undergo investigation to exclude systemic disease (see Table 112.2 ).

Dermal Melanocytosis

▪ Congenital dermal melanocytosis: • Mongolian spot

- ▪

Blue to blue–gray patch present at birth, whose primary location is lumbosacral

- ▪

More common in Asians

- ▪

Usually resolves during childhood

- ▪

Sparse dendritic melanocytes in the deeper dermis

Epidemiology

Dermal melanocytosis is usually present at birth or appears within the first weeks of life; rarely, lesions appear after early childhood . Both sexes seem to be affected equally. Dermal melanocytosis usually regresses during early childhood, but it can persist and was seen in 4% of 9996 Japanese males between 18 and 22 years of age. It occurs in all races, with a frequency in one study of 100% in Malaysians, 90–100% in Mongolians, Japanese, Chinese and Koreans, 87% in Bolivian Indians, 65% of blacks in Brazil, 17% of whites in Bolivia, but only 1.5% of whites in Brazil. The racial differences in the frequency of this abnormality suggest that genetic factors influence survival of dermal melanocytes (see Ch. 65 ). Microscopically, histologic findings consistent with dermal melanocytosis can be found in the presacral area of 100% of newborns, irrespective of race .

Pathogenesis

The blue color in dermal melanocytosis is secondary to melanin-producing melanocytes residing within the middle to lower dermis. Melanocytes appear in the dermis during the 10th week of gestation, and then either migrate into the epidermis or undergo cell death, except for melanocytes in the dermis of the scalp, extensor aspects of the distal extremities, and the sacral area. The latter is the most common site for dermal melanocytosis. The bluish coloration of dermal melanocytosis results from the Tyndall phenomenon: dermal pigmentation appears blue because of decreased reflectance of light in the longer-wavelength region compared with the surrounding skin. Longer wavelengths, such as red, orange and yellow, are not reflected, compared with the shorter wavelengths of blue and violet, which are reflected .

Clinical Features

The classic location is the sacrococcygeal and lumbar regions and the buttocks, followed by the back ( Fig. 112.7 ). Dermal melanocytosis may consist of a single or multiple patches and usually involves <5% of the body surface area. The lesions are macular and have a round, oval or angulated shape. The size varies from a few to more than 20 cm. The color varies from light blue to dark blue to blue–gray. Extrasacral (aberrant) variants tend to be more persistent, and there is overlap between persistent lesions and the entities adult-onset dermal melanocytoses, nevus of Ito, and patch blue nevus. Extensive dermal melanocytosis should raise the possibility of phakomatosis cesioflammea (type II phakomatosis pigmentovascularis [PPV]) and phakomatosis cesiomarmorata (type V PPV; see Ch. 104 ). When CALMs and satellite congenital melanocytic nevi reside within areas of dermal melanocytosis, there may be a rim that lacks dermal melanocytes around each lesion (see Fig. 112.7 ).

Pathology

Bipolar dendritic melanocytes are dispersed singly in the lower half or lower two-thirds of the dermis. These melanocytes are DOPA-positive and lie parallel to the epidermis between the collagen bundles without disturbing the normal architecture of the skin. Occasionally, persistent dermal melanocytosis has the histology of a blue nevus with involvement of the subcutis, muscle, and fascia by melanocytes. On electron microscopy, dermal melanocytosis shows fully developed melanocytes with exclusively mature, electron-dense melanosomes and very few premelanosomes.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of dermal melanocytosis includes primarily nevus of Ota (if there is facial involvement), nevus of Ito, and patch blue nevus. The latter has many names in the literature, including dermal melanocyte hamartoma, acquired dermal melanocytosis, and acquired linear dermal melanocytosis; clearly there is overlap with the rare adult-onset dermal melanocytosis. The clinical differential diagnosis may also include venous malformations or deep infantile hemangiomas and a contusion. Although the distinctive clinical presentation of dermal melanocytosis generally allows easy distinction from these entities, there have been reports of the misdiagnosis of child abuse.

Treatment

Persistent lesions may be treated with cover-up cosmetics or lasers (see nevus of Ota ).

Nevus of Ota and Related Conditions

- ▪

Nevus of Ota: • nevus fuscoceruleus ophthalmomaxillaris • oculodermal melanocytosis • congenital melanosis bulbi • oculomucodermal melanocytosis

- ▪

Nevus of Ito: • nevus fuscoceruleus acromiodeltoideus

- ▪

Nevus of Ota-like macules: • Hori’s nevus

Nevus of Ota

- ▪

Blue to blue–gray to blue–brown unilateral, or occasionally bilateral, facial patch

- ▪

More common in Asians and blacks

- ▪

More dermal dendritic melanocytes than in congenital dermal melanocytosis, but less than in blue nevus

Epidemiology

Nevus of Ota occurs predominantly in more darkly pigmented individuals, especially in Asians and blacks, but has also been described in Caucasians . Approximately 80% of all reported cases have been in women; however, this figure may be somewhat skewed as a result of greater cosmetic concerns in women. In Japan, nevus of Ota is seen in ~0.4–0.8% of all dermatologic patients. The lesion has two peaks of onset: the first (~50–60% of all cases) is during infancy (before the age of 1 year), with the majority present at birth, and the second (40–50%) is around puberty. Onset between the ages of 1 and 11 years and after 20 years is unusual. Although rare familial forms of nevus of Ota have been reported, the condition is generally not considered hereditary.

Pathogenesis

The blue to blue–gray color in nevus of Ota is due to melanin-producing melanocytes in the dermis. The larger concentration of melanocytes in nevus of Ota in comparison to congenital dermal melanocytosis is thought to indicate a hamartoma. The possibility of a hormonal influence in women has been raised. Somatic activating mutations in GNA11 or GNAQ were detected in up to 15% of cases of nevus of Ota, as compared to 65–75% of blue nevi (primarily GNAQ ) and 80–85% of primary uveal melanomas . Both of these genes encode α-subunits of G proteins that interact with endothelin receptor type B (see Ch. 65 ). In mice, germline mutations in Gnaq lead to an increase in dermal pigmentation. Of note, BAP1 mutations have been detected in cases that progressed to melanoma, pointing to a role in malignant transformation.

Clinical features

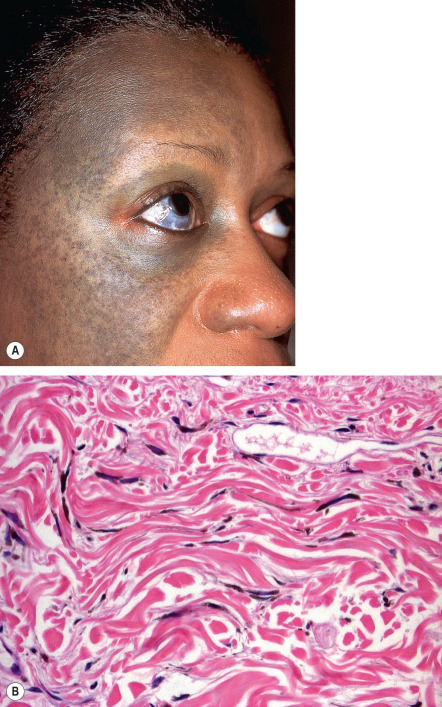

Nevus of Ota is usually characterized by a confluence of individual macules varying from pinhead-sized to several millimeters in diameter. The shape of the individual macules may be round, oval or serrated, whereas the overall appearance is that of an irregularly demarcated and often mottled patch. The overall size varies from a few centimeters to extensive unilateral and occasionally bilateral involvement ( Fig. 112.8A ). The color varies from shades of tan and brown to gray, blue, black and purple.

Nevus of Ota is usually unilateral and favors the distribution of the first two branches of the trigeminal nerve. The periorbital area, temple, forehead, malar area, earlobe, pre- and retroauricular regions, nose, and conjunctivae are the most common sites of involvement. A characteristic feature, which is seen in about two-thirds of patients, is the involvement of the ipsilateral sclera; rarely, nevus of Ota affects the cornea, iris, fundus oculi, retrobulbar fat, periosteum, retina, and optic nerve. Iris mammillations and glaucoma (~10% of patients) have been reported, but vision is usually not impaired. Other frequent sites of involvement are the tympanum (55%), nasal mucosa (30%), pharynx (25%), and palate (20%). Occasionally, the external auditory canal, mandibular area, lips, neck, and thorax are involved. In 5% to 15% of patients, the lesion is bilateral.

Nevus of Ota may extend over time and it persists for life. Fluctuations in the intensity of the color have been described, especially in association with periods of hormonal flux such as menstruation, puberty or menopause.

Uveal melanomas arising within nevi of Ota are unusual, estimated at 1 in 400 in Caucasians and even less often in Asians. As of 2016, 11 cases of cutaneous melanoma arising within a nevus of Ota had been reported in the literature . These typically presented in Caucasian patients as new subcutaneous nodules and did not adhere to the ABCD rules of melanoma. Other tumors such as atypical and borderline cellular blue nevi have also been described . In addition to the uveal tract, primary melanomas of the orbit, chiasma, and meninges have been observed in association with nevus of Ota as it is one of the entities that can have associated neuromelanosis and meningeal melanocytomas.

Related conditions

Nevus of Ito differs from nevus of Ota primarily in its area of involvement; the former corresponds to the distribution of the posterior supraclavicular and lateral cutaneous brachial nerves (which encompasses the supraclavicular, scapular, and deltoid regions). The clinical and histologic picture is the same as in nevus of Ota. There is a mottled appearance with both bluish and brownish macules. Nevus of Ito may occur as an isolated lesion or in association with an ipsilateral or bilateral nevus of Ota. Development of melanoma within a nevus of Ito is very rare . Acquired nevus of Ota-like macules (Hori’s nevus) are characterized by bilateral blue–gray to gray–brown macules of the zygomatic area and less often the forehead, upper outer eyelids, and nose. This entity has been reported primarily in Chinese or Japanese women ranging from 20 to 70 years of age. In contrast to nevus of Ota, the eye and oronasal mucosa are not involved, and it is most commonly misdiagnosed as melasma. A patch blue nevus , which overlaps with the rare disorder adult-onset dermal melanocytosis, presents as a diffusely gray–blue area that may have superimposed darker macules. The age of onset and sites of involvement vary, with some lesions having a linear distribution.

Pathology

The non-infiltrated areas in nevus of Ota show pigmented, elongated and dendritic melanocytes scattered among the collagen bundles ( Fig. 112.8B ). In comparison to dermal melanocytosis, the cells are more numerous and are located within the upper third of the reticular dermis. Occasionally, cells are found in the papillary dermis or even deep in the subcutaneous fat.

Hypermelanosis of the lower epidermis and an increase in basilar melanocytes may occur. The DOPA reactivity of the melanocytes in nevus of Ota varies: slightly pigmented cells are often strongly reactive, whereas heavily pigmented melanocytes often are not reactive, indicating minimal residual enzymatic activity. Melanocytes can be found clustering around blood vessels as well as sweat and sebaceous glands; occasionally, they are seen within vessel walls or in sweat ducts. Raised or infiltrated areas show a larger number of dendritic melanocytes forming cellular aggregates or clumps resembling blue nevi histologically.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of nevus of Ota and related conditions includes congenital dermal melanocytosis (Mongolian spot), adult-onset dermal melanocytosis, blue nevus (patch or plaque), melasma, partial unilateral lentiginosis (when it involves the face), a nevus spilus that develops blue nevi, venous malformations, and ecchymoses. Congenital dermal melanocytosis differs from nevus of Ota and other dermal melanocytoses due to its location in the lumbosacral region and its spontaneous regression during childhood.

Treatment

Nevus of Ota and nevus of Ota-like macules have been treated successfully by Q-switched ruby, alexandrite, and Nd:YAG lasers . Although malignant changes are rare in patients with nevus of Ota, patients with eye involvement should be followed more carefully by an ophthalmologist, since the majority of associated melanomas are ocular in origin and some patients develop glaucoma. Suspicious lesions, especially a new subcutaneous nodule, should be biopsied. Any complaint of neurologic symptoms requires further investigation.

Melanocytic Nevi

In dermatology, the term “nevus” is used to describe a hamartoma (e.g. epidermal nevus, sebaceous nevus) or a proliferation of nevomelanocytes. The remainder of this chapter focuses on the various types of melanocytic nevi, including associated genetic mutations ( Table 112.3 ) and genetic syndromes in which patients can develop numerous melanocytic nevi ( Table 112.4 ).

| GENES IMPLICATED IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF MELANOCYTIC NEVI | |

|---|---|

| Gene | Type of melanocytic nevus |

| BRAF | Common acquired melanocytic nevi (65–80%) |

| NRAS | Congenital melanocytic nevi (~80%), small minority of common acquired melanocytic nevi, congenital melanocytic nevus with hypophosphatemia (single case) |

| HRAS | Spitz nevi * , ** (~15%), deep penetrating nevi (6%), nevus spilus/speckled lentiginous nevi (100% in one series); also phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica |

| GNAQ | Blue nevi (50–85%, depending upon the study); also phakomatosis pigmentovascularis |

| GNA11 | Blue nevi (7–10%); also phakomatosis pigmentovascularis |

| BAP1 | Atypical epithelioid cell nevi/tumors (often polypoid and combined dermal nevi with large “spitzoid” cells) |

| PTEN | Nevi in patients with xeroderma pigmentosum (~60%) |

| PRKAR1A | Epithelioid blue nevi (mutation in the second allele in Carney complex), pigmented epithelioid melanocytomas |

* Also copy number increases of chromosome 11p where HRAS resides.

** Also Spitz nevi arising within a nevus spilus (sometimes mistakenly termed “agminated Spitz nevi”).

| GENETIC SYNDROMES ASSOCIATED WITH NUMEROUS ACQUIRED MELANOCYTIC NEVI |

|---|

| Familial atypical mole and melanoma syndrome * |

| BAP1 cancer syndrome – atypical epithelioid nevi/tumors, uveal melanomas, mesothelioma |

| Carney complex (NAME/LAMB syndromes) – see Table 112.2 |

| Turner syndrome – webbed neck, congenital lymphedema (partial or complete loss of X chromosome in females) |

| Noonan syndrome (mutations in multiple genes including PTPN11 , RAF1 , KRAS , SOS1 ) > other RASopathies (e.g. LEOPARD [Noonan with multiple lentigines] syndrome, cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome, Costello syndrome; see Ch. 55 ) |

| Ectrodactyly, ectodermal dysplasia, and cleft lip/palate syndrome (EEC syndrome; TP63 mutations) |

| Goeminne syndrome – torticollis, keloids, cryptorchidism, and renal dysplasia |

| Kuskokwim syndrome – congenital joint contractures, skeletal deformities ( FKBP10 mutations) |

| Mulvihill Smith syndrome – progeroid short stature with pigmented nevi |

| Trichorhinophalangeal syndrome type II (Langer–Giedion syndrome) |

| Tricho-odonto-onychial dysplasia |

* OMIM designation is “Susceptibility to cutaneous melanoma”.

Blue Nevus and Its Variants

▪ Blue nevus of Jadassohn–Tièche ▪ Dermal melanocytoma ▪ Nevus bleu ▪ Blue neuronevus

- ▪

Blue to blue–black, firm papule, nodule or plaque, often with an onset during childhood or adolescence

- ▪

Aggregates of dendritic, heavily pigmented melanocytes within the dermis

Epidemiology

Most blue nevi are acquired and while they usually arise during childhood or adolescence, up to a quarter can first appear in middle-aged adults. A congenital common blue nevus is unusual, but ~25% of cellular blue nevi are congenital.

Pathogenesis

Blue nevi represent benign tumors of dermal melanocytes . In general, dermal melanocytes disappear during the second half of gestation, but some residual melanin-producing cells remain in the dermis of the scalp, sacral region, and dorsal aspect of the distal extremities. These are the sites where blue nevi most commonly occur. The blue coloration of these nevi is the result of the Tyndall phenomenon (see above). Somatic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ (primarily the latter) have been detected in 50–85% of blue nevi, depending upon the study. As a consequence, the intrinsic GTPase activity of encoded α-subunits is blocked and the G protein becomes locked in a GTP-bound, constitutively active state .

Clinical Features

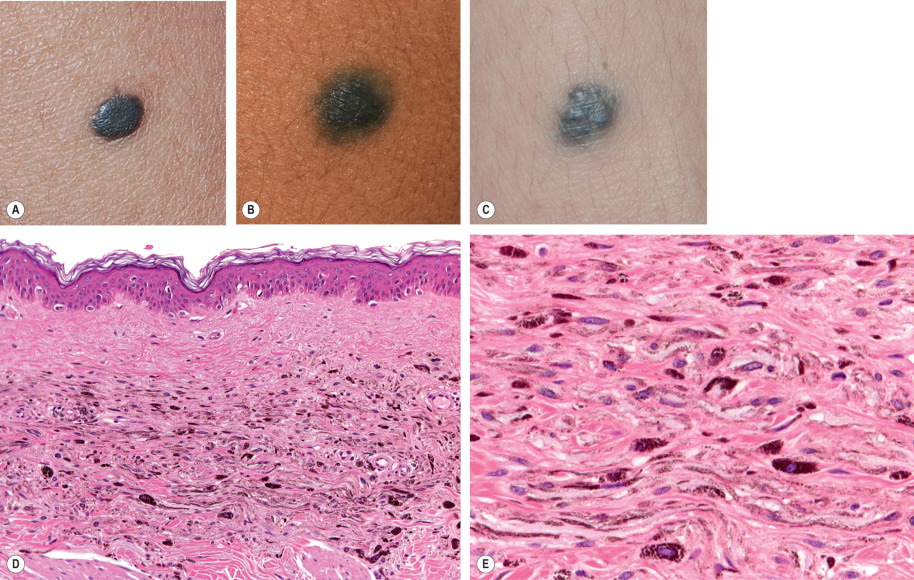

Common blue nevi

Common blue nevi are well-circumscribed, dome-shaped papules that are blue, blue–gray, or blue–black in color ( Fig. 112.9A–C ). They are usually 0.5 to 1.0 cm in diameter, rarely larger. The lesions may occur anywhere, but about 50% are found on the dorsal aspect of the hands and feet, with the face and scalp being other common sites. Blue nevi have been described in the oral and genital mucosae, cervix, prostate, spermatic cord, and lymph nodes. Over time, hypopigmentation can appear centrally within common blue nevi, and an “achromic” variant has been described.

Usually, blue nevi are solitary, but they may be multiple or agminated or may arise with a nevus spilus or plaque blue nevus. Concentric, target-like lesions (target blue nevi) have been described as well. Dermoscopically, a blue nevus is characterized by homogeneous blue–gray to blue–black pigmentation (see Ch. 0 ).

Cellular blue nevi

Cellular blue nevi are blue to blue–gray or black nodules or plaques, generally 1 to 3 cm in diameter but sometimes larger ( Fig. 112.10 ) . Their surface is often smooth but sometimes irregular. The most common sites are the buttocks, sacrococcygeal area and scalp, followed by the face and feet. Congenital cellular blue nevi, some with satellite lesions, have been reported, as have benign or malignant cellular blue nevi arising within congenital melanocytic nevi. The ratio of common blue nevus to cellular nevus is at least 5 : 1.

Epithelioid blue nevi

Epithelioid blue nevi were first reported as a feature of the Carney complex (see Table 112.2 ); however, they also may occur sporadically . These lesions have a predilection for the trunk and extremities and rarely develop on orogenital mucosa. Histologically, they may be indistinguishable from pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.

Pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma

This somewhat controversial term has been proposed as one that unifies epithelioid blue nevi (described above) and lesions previously reported as “animal-type”, “melanophagic”, or “pigment synthesizing” melanomas. The latter are characterized by marked melanin production and a resemblance to certain melanizing tumors in animals . The lesions seem to have a low-grade potential for regional metastases, but rarely for non-regional metastases; they almost never result in overt malignant behavior and death of patients. In one study, all eight epithelioid blue nevi that arose in patients with Carney complex (with confirmed PRKAR1A mutations) showed loss of expression of protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1-α (the product of PRKAR1A ) as did 28 (82%) of 34 sporadic pigmented epithelioid melanocytomas, suggesting a relationship .

Malignant blue nevi (cutaneous melanoma arising in or having features of blue nevus)

Malignant blue nevi are rare forms of cutaneous melanoma most commonly arising within cellular blue nevi . They tend to show progressive enlargement, often measuring several centimeters in diameter, and have a multinodular or plaque-like appearance. The scalp is the most common site of occurrence and lymph nodes are the most common sites of metastasis. Malignant blue nevi can arise in a previously benign cellular blue nevus, in a nevus of Ota or Ito, or de novo .

Pathology

The common or ordinary blue nevus is composed of elongated and often slightly wavy melanocytes with long, branching dendrites ( Fig. 112.9D,E ). The melanocytes, with their long axes parallel to the epidermis, lie grouped or in bundles in the upper and mid dermis. Occasionally, they extend into the subcutaneous tissue or approach the epidermis but do not alter it. Most of the melanocytes are filled with numerous fine melanin granules, often completely obscuring their nuclei as well as extending into their dendrites. Variable numbers of melanin-laden macrophages are also present. The amount of collagen is usually increased, giving the lesion a fibrotic appearance. Melanin content may be minimal in the hypopigmented variant.

In a cellular blue nevus , one often observes deeply pigmented dendritic melanocytes (as in a common blue nevus) in addition to nests and fascicles of spindle-shaped cells with abundant pale cytoplasm containing little or no melanin (see Fig. 112.10B ). The aggregates of spindle cells may be arranged in intersecting bundles extending in various directions, a disposition resembling the storiform pattern of neurofibroma. By electron microscopy, the spindle-shaped cells contain melanosomes with little or no melanization. However, melanin production within these cells and a transition to bipolar dendritic nevus cells have been documented.

Penetration of rounded, well-defined cellular islands into the subcutaneous tissue is frequently noted in cellular blue nevi. Some of the cells may appear atypical, with nuclear pleomorphism accompanied by multinucleated giant cells, rare mitoses, and inflammatory infiltrates. Lastly, while there are classic histopathologic differences between common and cellular blue nevi, overlapping features are seen in some lesions.

Occasionally, lymph nodes draining the anatomic site of a cellular blue nevus contain blue nevus cells. The foci, found either in the marginal sinuses or in the capsule, are usually small, discrete and peripherally located. They may result from passive transport or represent arrested migration from the neural crest. These “benign metastases” are found in 5% of the reported cases of cellular blue nevi.

Atypical cellular blue nevi demonstrate one or more of the following features compared to conventional cellular blue nevi: larger size (>1–2 cm), asymmetry, ulceration, infiltrating features, cytologic atypia, mitoses, and necrosis . Such lesions have been associated with lymph node metastases and evolution to frank melanoma. These lesions require further study since their biologic potential is difficult to predict.

Epithelioid blue nevi and pigmented epithelioid melanocytomas are typified by dermal (and sometimes junctional) aggregates of enlarged epithelioid melanocytes often containing coarsely granular melanin pigment and prominent nucleoli. These cells are often admixed with heavily pigmented spindled and dendritic melanocytes as well as melanophages. Cytologic atypia and dermal mitoses may be present.

Combined nevus is discussed later in the chapter.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of a common blue nevus includes traumatic tattoo, combined nevus, vascular lesions including venous lake and angiokeratoma, sclerosing hemangioma, primary and metastatic melanoma, pigmented spindle cell nevus, atypical nevus, dermatofibroma, papular pigmented basal cell carcinoma, and glomus tumor. For cellular blue nevus, especially with satellitosis, malignant blue nevus needs to be considered, and when the lesion is on the face, nevus of Ota. Blue nevi also need to be distinguished from a cutaneous neurocristic hamartoma, a complex proliferation of nevus cells, Schwann cells, and pigmented dendritic and spindled cells.

Histologically, epithelioid blue nevi and pigmented epithelioid melanocytomas must be differentiated from primary or metastatic melanoma as well as tumoral melanosis due to complete or almost complete regression of melanoma. Cellular blue nevi, especially those with atypical features, need to be distinguished from malignant blue nevi. Occasionally, cutaneous metastases of melanoma can simulate a blue nevus.

Treatment

Blue nevi that are <1 cm in diameter, are clinically stable, do not have atypical features and are located in a typical anatomic site do not require removal. On the other hand, histologic evaluation should be strongly considered for lesions that appear de novo , are multinodular or plaque-like, or have undergone change. Atypical cellular blue nevi and pigmented epithelioid melanocytomas should be resected completely in order to prevent recurrence and because of their risk for malignant transformation or metastases. The approach to typical cellular blue nevi varies, but if observation is difficult (e.g. lesions on the scalp), excision can be considered.

Common Acquired Melanocytic Nevi

▪ Nevocellular nevus ▪ “Mole”

- ▪

A junctional nevus is a brown to black macule with melanocytic nests at the junction of the epidermis and dermis

- ▪

An intradermal nevus is a skin-colored or light brown papule with nests of melanocytes in the dermis

- ▪

A compound nevus is a brown papule with combined histologic features of junctional and intradermal nevi

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree