Acne and Related Disorders

Overview

Acne, the most common skin disorder in the United States, is an embarrassing problem for many teenagers, but it is not limited to that age group. It may develop before puberty in either sex, or it may first be seen in adults, particularly in women.

Acne is a condition that involves the pilosebaceous apparatus of the skin. Acne vulgaris, or common acne (referred to herein as adolescent acne), begins in the teen or preteen years. In general, it becomes less active as adolescence ends but may continue into adulthood.

Acne that initially occurs in adulthood is designated postadolescent acne or adult-onset acne. Despite the clinical similarities and occasional overlapping of adolescent and postadolescent acne, the pathogenesis and treatment of each are somewhat different.

Acnelike disorders, such as neonatal acne, drug-induced acne, rosacea, and other so-called acneiform conditions, are also considered separate entities because of differences in pathogenesis.

That being said, no clear lines separate the various types of acne; much of acne’s features overlap and lie along a continuum. However, readers may find the following classifications useful for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

Adolescent Acne (Acne Vulgaris)

Preteen acne and adolescent acne, which may persist into adulthood

Postadolescent Acne

Female adult-onset acne, acne excoriée des jeunes filles

Male adult-onset acne

Acnelike Disorders

Rosacea

Perioral dermatitis

Neonatal acne

Drug-induced acne

Endocrinopathic acne

Physically induced and occupational acne

Folliculitis (see Chapter 5, “Superficial Bacterial Infections, Folliculitis, and Hidradenitis Suppurativa”)

Hidradenitis suppurativa (see Chapter 5, “Superficial Bacterial Infections, Folliculitis, and Hidradenitis Suppurativa”)

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (see Chapter 10, “Hair and Scalp Disorders Resulting in Hair Loss”)

Acne keloidalis (see Chapter 10, “Hair and Scalp Disorders Resulting in Hair Loss”)

Adolescent Acne

Basics

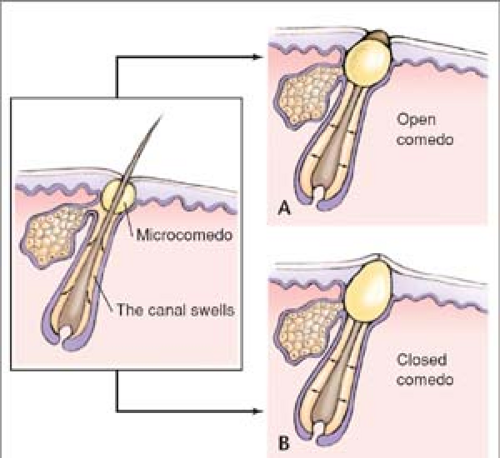

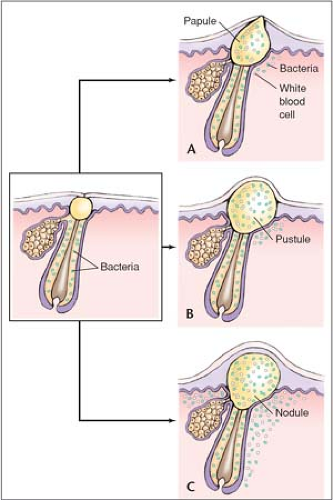

Teenage acne has a strong tendency to be hereditary and is less likely to be seen in Asians and dark-skinned people. Lesions begin during puberty when androgenic hormones cause abnormal follicular keratinization, which then blocks the sebaceous duct. This blockage results in a microcomedo (the microscopic primary lesion of adolescent acne). The microcomedo enlarges to become the visible comedo: the noninflammatory blackhead or whitehead. Alternatively, the microcomedo may become an inflammatory lesion, such as a papule or pustule.

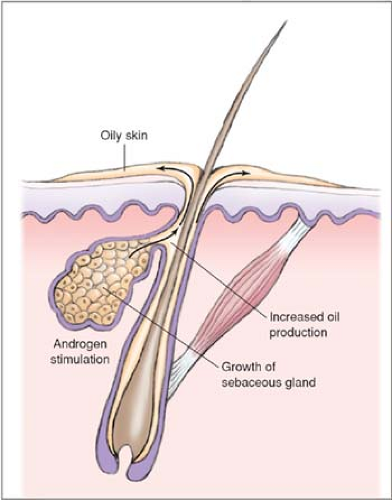

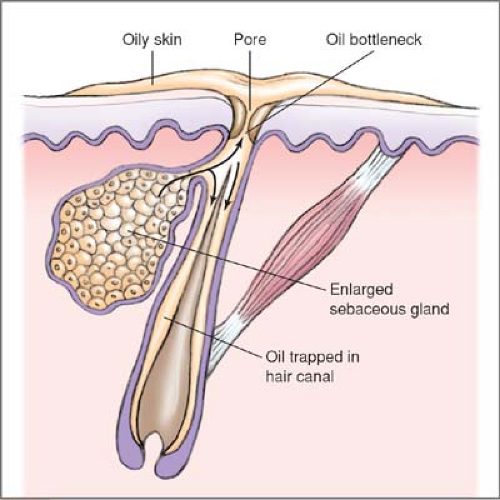

The development of inflammatory lesions theoretically occurs as follows: Androgenic hormones stimulate sebaceous glands to increase in size and function and thus to produce more sebum. The skin becomes oilier and the microcomedo becomes more hospitable to the anaerobe Propionibacterium acnes. Then P. acnes produces lipases that digest the lipids into fatty acids, causing a rupture of the microcomedo that incites an inflammatory cell response (Illus. 1.1–1.4) will be helpful.

Myth: Blackheads are caused by dirt.

Fact: They are black because of oxidized melanin. Blackheads, or open comedones, are collections of sebum and keratin that form within follicular openings and that, when exposed to air, become oxidized and turn black.

Myth: Acne should disappear by the end of adolescence.

Fact: Some women have acne that persists well past adolescence. Others have an initial episode in their 20s or 30s.

Myth: Acne is caused or worsened by certain foods, such as chocolate, sweets, and greasy junk food.

Fact: Despite occasional personal anecdotes and persistent cultural myths, acne is probably not significantly influenced by diet.

Myth: A dirty face exacerbates acne; therefore, scrubbing the face daily helps clear it up.

Fact: Scrubbing and rubbing a face that has acne, particularly inflammatory acne, will only serve to irritate and redden an already inflamed complexion. Instead, the face should be washed daily with a gentle cleanser.

Myth: Frequent facials are beneficial.

Fact: Professional facials and at-home scrubs, astringents, and masks are generally not recommended because they tend to aggravate acne.

Description of Lesions

Acne lesions are designated as inflammatory or noninflammatory (comedonal), or a combination of the two.

Inflammatory Lesions

Papules: Superficial red “pimples” that may have crusted, scabbed surfaces caused by dried pustules or by picking or squeezing.

Pustules: Superficial raised lesions containing purulent material, generally found in the company of papules.

Macules: The remains of formerly palpable inflammatory lesions that are in the process of healing from therapy or spontaneous resolution. They are flat, red or sometimes purple (violaceous) blemishes that slowly heal and may occasionally form a depressed, atrophic scar.

“Acne cysts” (nodules): Large, deep papules or pustules. Acne “cysts” are not really cysts. True cysts are neoplasms that have an epithelial lining. Acne “cysts” do not have an epithelial lining; they are composed of poorly organized conglomerations of inflammatory material.

Noninflammatory (Comedonal) Lesions

A comedo is a collection of sebum and keratin that forms within follicular ostia (pores) (Fig. 1.4).

Open comedones (blackheads) have large ostia that are black as a result of oxidized melanin.

Closed comedones (whiteheads) have small ostia.

Follicular prominence. These blackheadlike, dilated pores are frequently seen on the nose and cheeks in acne patients (Fig. 1.5).

Severity

Acne may be further classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Mild acne consists of comedones and/or occasional papules and pustules.

Moderate acne is more inflammatory, with relatively superficial papules and/or pustules (papulopustular acne); comedones may also be present. Lesions may heal with scars.

Severe acne (“cystic” or nodular acne, acne conglobata) has a greater degree, depth, and number of inflammatory lesions: papules, pustules, nodules, “cysts,” and possibly abscesses. Sinus tracts, significant scarring, and keloid formation may also be evident (Fig. 1.6).

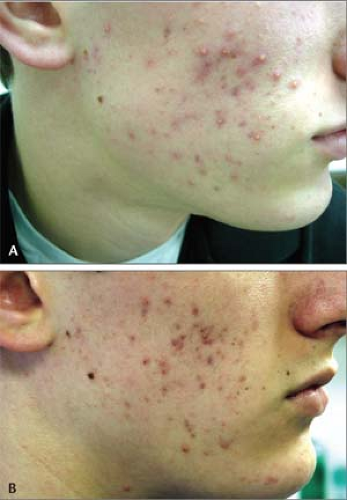

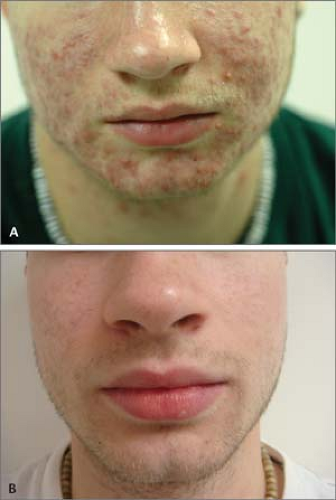

1.3 A and B A: Inflammatory acne. Nodules. Severe “cystic” acne. B: The patient 6 months later after treatment with isotretinoin (Accutane). |

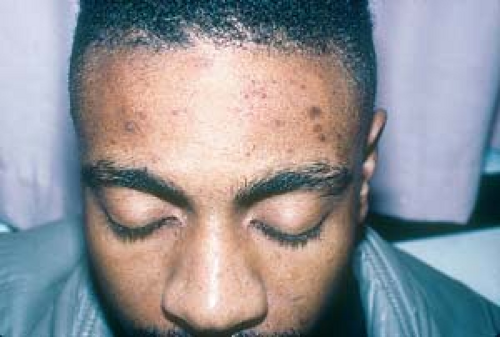

1.5 Follicular prominence. These blackheadlike, dilated ostia (pores) are frequently seen on the nose and cheeks in acne patients. |

Distribution of Lesions

Acne most commonly erupts in areas of maximal sebaceous gland activity: the face, neck, chest, shoulders, back, and upper arms.

Clinical Manifestations and Sequelae

The more severe inflammatory lesions of acne are prone to heal with atrophic or pitted (“ice-pick”) scars on the face, and hypertrophic scars or keloids on the trunk (Fig. 1.7).

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur, particularly in patients with darker skin (Fig. 1.8).

The negative psychologic effects of acne (e.g., lowered self-esteem) and its impact on limiting employment opportunities and social functioning are among the overriding concerns of individuals who have moderate to severe acne.

Diagnosis

Adolescent acne is easy for both the patient and practitioner to recognize.

However, specific underlying causes of acne (e.g., hyperandrogenism) should be considered in certain female patients (see following).

Keratosis Pilaris

(See Chapter 2, “Eczema, Atopic Dermatitis.”

Keratosis pilaris consists of small, follicular, horny spines. The tiny papules may resemble acne when they are inflamed.

The lesions of keratosis pilaris are most often seen on upper outer arms (Fig. 1.9), back, thighs, and lateral face.

In children, the lateral sides of the cheeks are frequently involved. These findings are commonly mistaken for acne (Fig. 1.10).

Folliculitis

See Chapter 5, “Superficial Bacterial Infections, Folliculitis, and Hidradenitis Suppurativa.”

Goals

The three main therapeutic goals are:

To prevent scarring

To help improve the patient’s appearance

To make every effort to control acne with topical therapy alone

General Principles

Treatment of acne should be individualized and frequently involves a trial-and-error approach that begins with those agents that are known to be most effective, least expensive, and have the fewest side effects.

Acne is a multifactorial disease; therefore, appropriate therapy often involves the use of more than one agent, each of which targets a different pathogenic factor.

Mild acne can often be managed successfully with over-the-counter (OTC) remedies.

Oral medications should be tapered as soon as control is achieved.

A patient should be advised not to squeeze or pick lesions.

Topical Therapies

Notwithstanding the testimonials seen on late-night television infomercials for acne preparations, no “one size fits all” treatment for acne exists. In fact, the active ingredients in these advertised preparations can be obtained less expensively in many OTC products.

Benzoyl Peroxide

See Table 1.1.

In addition to being potent antibacterial agents, benzoyl peroxide preparations improve both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions (comedones).

They dry and peel the skin, and they help clear blocked follicles.

Benzoyl peroxide may be used alone to treat mild acne, but for more severe cases, it should be used in conjunction with topical retinoids, as well as topical or systemic antibiotics.

Table 1.1 Benzoyl Peroxide–Containing Preparations

OVER-THE-COUNTER PREPARATIONS

Oxy-5, Oxy-10

5%, 10% benzoyl peroxide

Clear by Design

2.5% benzoyl peroxide gel

Clearasil 10%

10% benzoyl peroxide lotion

PRESCRIPTION FORMULATIONS

Desquam-Xerosis

5%, 10% benzoyl peroxide gel (water based)

Desquam-E

2.5%, 5%, 10% benzoyl peroxide gel (water based)

Bevoxyl

4%, 8% benzoyl peroxide gel (water based)

Triaz pads

3%, 6%, 10% benzoyl peroxide gel (water based)

ADVANTAGES

DISADVANTAGES

Available over the counter

No reported bacterial resistance

Often irritating (causes stinging, redness, and scaling)

Available in many formulations, including cream and liquid (water-based gels less irritating than alcohol-based preparations)

Contact sensitivity may occasionally occur

May bleach clothing and bed linen

Benzoyl peroxide is an ingredient of many brand-name OTC products, such as Clearasil, Oxy 5, and Oxy 10, as well as less expensive generics. It is available in water- and alcohol-based vehicles, soaps, medicated pads, and washes.

Lower-strength (e.g., 2.5%) preparations are less irritating and probably as effective as the 5% and 10% concentrations.

The addition of zinc to benzoyl peroxide in several newer products, such as Triaz, may enhance efficacy.

Benzoyl peroxide is also available in combination with erythromycin (Benzamycin) and clindamycin (Benza-Clin and Duac).

How to Use Benzoyl Peroxide

Beginning with a lower strength preparation, benzoyl peroxide is applied sparingly once or twice daily, in a thin layer on acne-prone areas.

Irritation and burning are not uncommon but usually resolve in 2 to 3 weeks.

Topical Retinoids

See Table 1.2.

Topical retinoids are primarily comedolytic (i.e., they treat comedones); they also have potent anti-inflammatory effects.

In addition, retinoids facilitate the penetration of, and may be used in combination with, other topical antiacne agents such as benzoyl peroxide.

These agents help “plump up” the skin and make enlarged pores (follicular prominence) less obvious.

All retinoids may produce sun sensitivity.

They should not be used during pregnancy or breast-feeding (although no studies have shown them to be harmful to the fetus).

Table 1.2 Topical Retinoids

Brand Name

Generic Name

Advantages/Disadvantages

Strengths

Sizes

Retin-A cream, gel

Tretinoin

Available in various strengths and less expensive generic formulations

Creams: 0.025%, 0.05%, 0.1%

20, 45 g

Often irritating

Gels: 0.01%, 0.025%

Retin-A Micro topical gel

Tretinoin

Less irritating than other forms of Retin-A

0.04%, 0.1%

20, 45 g, 50-g pump dispenser

Avita cream, gel

Tretinoin

Less irritating than Retin-A

One strength

0.025%

20, 45 g

Differin cream, gel, solution, pledgets

Adapalene

Less irritating than Retin-A; causes less sun sensitivity than Retin-A

One strength

0.1%, 0.3%

15, 45 g 30 ml, #60

Tazorac dream, gel

Tazarotene

Possibly more effective and faster acting than Retin-A; two strengths

Irritating; expensive

0.05%, 0.1%

30, 100 g

Table 1.3 Topical Antibioticsa

BRAND NAME

GENERIC NAME

ADVANTAGES/DISADVANTAGES

SIZES

A/T/S solution, gel

Erythromycin 2%

Effective for postadolescent acne, rosacea; irritation is infrequent

Often used in conjunction with benzoyl peroxide and/or retinoids

60 ml, 30 g

Akne-Mycin ointment

Erythromycin 2%

Least irritating topical antibiotic; excellent for atopic skin

Somewhat messy to apply

25 g

Cleocin T solution, gel, lotion

Clindamycin 1%

Effective for postadolescent acne, rosacea

Lotion is less irritating than solution and gel

30, 60 ml

Evoclin foam

Clindamycin 1%

Easy to apply to large and hairy areas

50, 100 g

Theramycin Z

Erythromycin 2%/zinc acetate

Contains zinc

50, 100 g 60 ml

Ziana

Clindamycin 1.2%/tretinoin 0.25% gel

New combination drug

30, 60 g

aBacterial resistance is possible with all of these agents.

How To Use Topical Retinoids

Topical retinoids are applied once daily, usually at bedtime.

Beginning with lower-strength preparations, such as tretinoin 0.025%, adapalene cream 0.1%, or tazarotene cream 0.05%, they are applied sparingly in a thin layer over the acne-prone areas. In time, higher concentrations can be applied.

Patients who exhibit sensitivity may use it every other day, or less frequently, until they develop a tolerance to it.

The area of application should first be washed and thoroughly dried.

Side effects may include erythema, dryness, and peeling. These usually resolve after 3 weeks.

Use of a sunscreen should be advised, because tretinoin and adapalene may cause photosensitivity in some patients.

Table 1.4 Combination Topical Antibiotic and Benzoyl Peroxide Agentsa

BRAND NAME

GENERIC NAME

ADVANTAGES/DISADVANTAGES

SIZES

Benzamycin gel

Erythromycin 3%/benzoyl peroxide 5%

Less expensive than comparable products

Refrigeration necessary

23.3, 46.6 g

BenzaClin gel

Clindamycin 1%/benzoyl peroxide 5%

No refrigeration necessary; 50-g pump dispenser

25, 50 g

Duac gel

Clindamycin 1%/benzoyl peroxide 5%

No refrigeration necessary

45 g

aNo bacterial resistance is reported with these agents.

Topical Antibiotics

See Table 1.3.

Preparations that contain the topical antibiotics clindamycin and erythromycin are active against P. acnes.

In addition to their antibacterial action, these drugs have an anti-inflammatory action that helps clear inflammatory acne lesions (papules and pustules).

Topical clindamycin and erythromycin are considered equally effective.

Drug resistance has been reported with these antibiotics.

How To Use Topical Antibiotics

These agents are applied once or twice daily, in a thin layer across the acne-prone areas.

Irritation and burning are uncommon and may be avoided by using an ointment-based erythromycin such as Akne-Mycin or clindamycin (Cleocin) in a lotion preparation.

Topical antibiotics are available in a variety of vehicles, including creams, lotions, ointments, gels, and solutions.

Combination of Topical Antibiotic and Benzoyl Peroxide

See Table 1.4.

Benzamycin, BenzaClin, and Duac gels are the most commonly prescribed formulations.

The combination of erythromycin and clindamycin with benzoyl peroxide helps prevent bacterial resistance furthermore, there appears to be a synergistic effect (the combination appears to be more effective than either drug used alone) when clindamycin and erythromycin are combined with benzoyl peroxide.

How To Use Combination of Topical Antibiotics and Benzoyl Peroxide

These agents are applied sparingly once daily to acne-prone areas.

The same cautions apply as for benzoyl peroxide. Dryness, erythema, and pruritus are the most common side effects.

Alternative Topical Prescription Drugs

These include azelaic acid (Azelex 20%), as well as older preparations that contain sulfur and sodium sulfacetamide such as Sulfacet-R lotion, Novacet lotion, and Klaron lotion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree