Bites, Stings, and Infestations

Overview

In much of the world, insect bites commonly serve as vectors that transport diseases such as malaria, leishmaniasis, filariasis, and rickettsial diseases. In modern industrial societies, insect bites are more of a nuisance than a potential carrier of a life-threatening illness. On the East Coast and in the Midwest of the United States, mosquitoes and biting flies as well as ticks account for most bites. In arid areas, including much of the Southwest and parts of California, flying insects are less common, and crawling arthropods are the primary cause of bites and stings.

West Nile virus, of much concern in the United States, is a mosquito-borne infection that can cause encephalitis. It was originally seen in New York State in 1999 and is now being reported throughout the country.

Insects, ticks, mites

Insects, ticks, mites

Insect bite reactions

Lyme disease (lyme borreliosis)

Scabies: mite infestation

Lice infestations (pediculosis)

Lice infestations (pediculosis)

Head lice (pediculosis capitis)

Body lice (pediculosis corporis)

Pubic lice

Waterborne stings and seashore infestations

Waterborne stings and seashore infestations

Jellyfish stings

Seabather’s eruption (“sea lice”)

Cutaneous larva migrans (“creeping eruption”)

Basics

Insects that bite include mosquitoes, fleas, flies, ticks, chiggers, and lice. Mosquito and fly bites occur most often from outdoor exposures, particularly in the summer. Flea bites are most often acquired indoors from pets.

Insects that sting include bees, wasps, hornets, and fire ants.

There is individual variability in the attraction of insects, possibly related to pheromones. Furthermore, reactions to bites and stings are probably related to individual hypersensitivity.

The physical insult of an insect bite or sting causes little injury; instead, lesions occur as a result of the body’s immune response to injected foreign chemicals and proteins introduced by the bite or sting. The time it takes for reactions to develop reflects the immune mechanism involved.

Pathogenesis

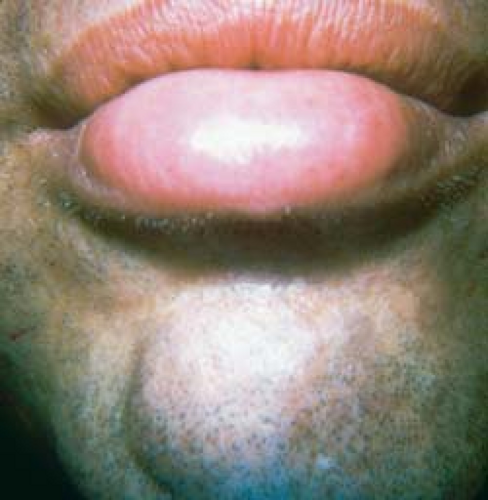

Immediate hivelike skin lesions reflect hypersensitivity to the bite or sting. They are mediated by immunoglobulin E (Fig. 20.1).

Delayed pruritic papules, nodules, and vesicles usually become symptomatic within 48 hours after the insult. They are manifestations of delayed hypersensitivity (type IV cell-mediated immunity).

Description of Lesions

Bite reactions typically present as intensely pruritic erythematous papules that commonly are excoriated.

Bite reactions may be indistinguishable from ordinary hives.

20.1 Angioedema caused by a bee sting. This patient developed an immediate hypersensitivity reaction after being bitten on the lip.

20.2 Flea bites. Note the arrangement of lesions in groups of three (“breakfast, lunch, and dinner”); the fourth lesion probably represents a “midnight snack.”

Grouping of lesions often occurs, particularly after flea bites (“breakfast, lunch, and dinner”; Fig. 20.2).

Lesions may have a central punctum and crust and also may become vesicobullous (Fig. 20.3).

Insect bite reactions are also known as papular urticaria when lesions persist for longer than 48 hours.

Distribution of Lesions

Lesions are found on exposed areas, more often on nonclothed body parts such as distal lower extremities, forearms, and hands.

The papules of flea bites are typically asymmetric in distribution.

Lesions are also commonly seen on the lower legs, forearms, lower trunk, and waist; the axillary and anogenital areas are usually spared. Flying insects tend to bite on the upper trunk or extremities, whereas crawling insects tend to bite or sting on the lower trunk or extremities. Although this is not always true, it often helps narrow down the cause.

Clinical Manifestations

Insect bites may be a chronic, recurrent problem or simply a nuisance.

The purpose of bites is usually to obtain a blood meal, which means that they often occur in multiples. The purpose of stings is usually self-defense, which means that they occur singly; the glaring exception is fire ants, which sting as much as they can.

Itching may be intense and may persist for weeks.

Secondary bacterial infection may occur.

Stings generally cause immediate pain and are therefore usually remembered.

Bites often go unnoticed, and the lesions that arise from them may not appear for days after the bite because of what is often a delayed immune-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. Consequently, a patient may seek medical advice for unexplained itchy bumps or blisters. Presumably, bites go unnoticed because it is to the arthropod’s advantage to obtain its blood meal without being detected, which serves to increase its survival value.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually made on clinical appearance and history.

Inquiry about household pets currently and formerly residing in the house may be a clue to the diagnosis. If the residence was formerly host to a dog or cat infested with fleas, the fleas left behind may have found new human hosts.

A skin biopsy is not diagnostic, but it may show suggestive findings consisting of a dense lymphocytic infiltrate (resembling lymphoma) with many eosinophils. The responsible agent is rarely found in a biopsy specimen.

Urticaria Unrelated to Insect Bites

See also Chapter 17, “Drug Eruptions.”

This type of urticaria lacks a central punctum.

It is often indistinguishable from insect bites.

Fiberglass Dermatitis

Nonspecific itching is noted.

The patient has a history of exposure (e.g., works with roofing materials).

Scabies

See the discussion later in this chapter.

A careful history and knowledge of the patient’s environment and possible exposures should be sought.

Symptoms may persist for weeks after the original bites.

Other causes should be diligently sought if symptoms persist for more than 4 to 6 weeks.

Patients who seek medical help generally do not consider “mundane” insect bites to be the cause of their dermatosis or itching; rather, they seek attention because they assume that other factors cause their problem.

Poisons normally used by exterminators do not kill fleas.

Insect repellents that contain N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) help prevent bites and stings.

Acute reactions to stings are treated symptomatically with topical or intralesional steroids and oral antihistamines; people with severe reactions from stings may profit from desensitization therapy.

Anaphylactic reactions require epinephrine, systemic steroids, and antihistamines.

If flea infestation is suspected, pets should be evaluated by a veterinarian. If fleas are present in the home, thorough vacuuming and shampooing of flea-infested areas and sometimes even fumigation may be necessary.

Insect Bite Reactions

20.4 Lyme disease, erythema migrans. A solitary, annular, targetlike, erythematous plaque of erythema migrans is seen. |

Lyme Disease (Lyme Borreliosis)

Basics

Lyme disease, or Lyme borreliosis (LB), is a systemic infection caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Bacteria are introduced into the skin via a bite from an infected Ixodes tick.

The tick has to be attached for 24 hours for the organism to be transmitted.

Once in the skin, the spirochete may stay localized at the site of inoculation, or it may disseminate via the blood and lymphatics. Hematogenous dissemination can occur within days or weeks of the initial infection. The organism can travel to other parts of the skin, the heart, the joints, the central nervous system, and other parts of the body.

The tick vector of LB, I. dammini, is found in the northeastern and midwestern United States, where most cases are reported. I. scapularis in the southeastern United States, I. pacificus on the Pacific coast, and I. ricinus, the sheep tick, in Europe are also vectors. Because the disease depends on deer, mice, ticks, and bacteria, it is limited geographically to the areas where all these organisms are present.

LB can occur in any season, although it is most prevalent during the warmer months from May through September during the nymphal stage of the tick. The ticks cling to vegetation (not trees) in grassland, marshland, and woodland habitats. They transfer to animals and humans brushing against the vegetation.

Description of Lesions

Initially, the LB lesion is a red macule or papule at the site of a tick bite. The bite itself usually goes unnoticed (only 15% of patients report a tick bite). Approximately 2 to 30 days after infection, the rash appears.

The lesion expands to form an annular erythematous lesion, erythema migrans (EM), which is the classic lesion of LB (Fig. 20.4). The lesion measures from 4 to 70 cm in diameter, generally with central clearing.

The center of the lesion, which corresponds to the putative site of the tick bite, may become darker, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic (Fig. 20.5).

Lesions may be confluent (not annular), and concentric rings may form.

Multiple lesions occur in approximately 20% of patients, likely a result of bacteremia (Figs. 20.6 and 20.7). These secondary lesions tend to be more uniform in morphology than the primary lesion.

Distribution of Lesions

Common sites are the thigh, groin, trunk, and axillae.

Because secondary lesions spread hematogenously, they are less restricted than primary lesions in terms of location.

Clinical Manifestations

Early Lyme Disease

At the early stage of disease, flulike symptoms, such as malaise, arthralgias, headaches, and a low-grade fever and chills, may occur. Other symptoms include stiffness of the neck and difficulty in concentrating.

The EM rash itself is usually asymptomatic.

Intermediate, Chronic, and Late Lyme Disease

Some of the signs and symptoms of LB may not appear for weeks, months, or even years after the initial tick bite and are believed to be caused by immunopathogenic mechanisms. The signs and symptoms of intermediate, chronic, and late Lyme disease include:

Arthritis in one or more large joints; nervous system problems that may include pain, paresthesias, Bell’s palsy, headaches, and memory loss; and cardiac dysrhythmias.

Rarely, a lesion of lymphocytoma cutis may develop, usually occurring on the earlobe or nipple. These lesions are bluish red nodules.

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) is a manifestation of chronic LB that begins as an inflammatory phase marked by edema and erythema, usually on the distal extremities. Later, atrophy occurs, and thin “cigarette-paper” skin is seen. Because of the loss of subcutaneous fat, underlying venous structures are more visible, and the skin becomes thin, atrophic, and dry.

Both lymphocytoma cutis and ACA are very rare findings in the United States and are seen primarily in Europe. The clinical differences probably result from the different antigenic strains of Borrelia.

Late Lyme disease refers to symptoms, primarily rheumatologic and neurologic, that occur months to years after initial infection. It is not unusual for patients to first present with late extracutaneous symptoms without ever having had an initial EM lesion or other overt symptoms of early Lyme disease. This may occur because the patient was asymptomatic or because early disease was not recognized by the patient or correctly diagnosed by the health care provider.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of LB is often difficult because the disease mimics many other conditions.

Viral infections, such as influenza and mononucleosis, also may manifest with rash, aches, fever, and fatigue.

Drug eruptions and insect bite reactions other than those caused by the Ixodes tick closely match the rash of early LB.

Early Diagnosis

To diagnose early LB, the following are important:

There is a history of tick exposure or bite in an area endemic for LB.

The specific tick is identified as a potential vector of LB.

The various presentations of EM are recognized.

Laboratory Testing

Serologic testing, using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot analyses for B. burgdorferi, is notoriously unreliable.

At the early presenting stage of LB, serologic testing has been reported to be positive in only 25% of infected patients. After 4 to 6 weeks, approximately 75% of these patients test positive, even after antibiotic therapy.

Patients with past LB and those who have been vaccinated may be persistently seropositive.

The poor reputation of serologic testing is derived somewhat from the many false-negative test results of patients treated very early in the course of the disease and from the many misdiagnosed cases of supposed LB.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends a two-step testing procedure consisting of a screening ELISA or immunofluorescent assay followed by a confirmatory Western immunoblot test on any samples with positive or equivocal results on ELISA.

Infrequently, spirochetes may be identified using silver or antibody-labeled stains.

Other diagnostic measures, such as polymerase chain reaction and cultures for B. burgdorferi have met with some success; however, these techniques are time-consuming and expensive. The Borrelia organism is fastidious, and culture of skin biopsy specimens is not readily available.

Tinea Corporis

See Chapter 7, “Superficial Fungal Infections.”

There may be a history of exposure to fungus.

Lesions are also annular (ringlike) and clear in the center; however, tinea corporis has an “active” scaly border (epidermal involvement).

Lesions are potassium hydroxide positive (Fig. 20.8), or the fungal culture grows dermatophytes.

Tinea corporis generally itches.

Acute Urticaria

See Chapter 18, “Diseases of Vasculature.”

At times, this may be indistinguishable from LB.

Lesions may have eccentric shapes (Fig. 20.9).

Individual lesions disappear within 24 hours.

It generally itches.

Granuloma Annulare

For a full discussion of this condition, see Chapter 4, “Inflammatory Eruptions of Unknown Cause.”

Erythema Multiforme

For a full discussion of this condition, see Chapter 25, “Cutaneous Manifestations of Systemic Disease.”

Tick Recognition

Ixodes ticks are much smaller than dog ticks. In their larval and nymphal stages, they are no bigger than a pinhead; unengaged adult ticks are the size of the head of a match (Fig. 20.10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree