Fig. 9.1

Epigastric hernia

9.2.2 Umbilical Hernias

The umbilicus is formed by the umbilical ring of the linea alba. Intra-abdominally, the round ligament (ligamentum teres) and paraumbilical veins join into the umbilicus superiorly, and the median umbilical ligament (obliterated urachus) enters inferiorly. An umbilical hernia traverses the fibromuscular ring of the umbilicus (Fig. 9.2). This hernia is most commonly found in infants and children, is congenital in origin, and often resolves without treatment by the age of five. An acquired umbilical hernia may also be seen in an adult, and this hernia is more common in women with a history of multiple pregnancies and in patients with obesity or with increased abdominal pressure resulting from ascites and chronic bowel distention.

Fig. 9.2

Umbilical hernia

Umbilical hernia is more common in those who have only a single midline aponeurotic decussation compared with the normal decussation of fibers from all three lateral abdominal muscles. Strangulation is unusual in most patients; however, strangulation or rupture can occur in chronic ascitic conditions. Small asymptomatic umbilical hernias barely detectable on examination need not be repaired. Adults who have symptoms, a large hernia, incarceration, thinning of the overlying skin, or uncontrollable ascites should have hernia repair. Spontaneous rupture of umbilical hernias in patients with ascites can result in peritonitis and death [1, 4, 5].

9.2.3 Spigelian Hernias

Although spigelian hernias are uncommon (accounting for 0.1–2 % of all abdominal wall hernias), its diagnostic incidence has been rising because of improved imaging technology and incidental identification during laparoscopy. They occur in the anterolateral aspect of the lower abdomen, along the semilunar line formed by fibrous union of the rectus sheath with the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis and oblique abdominal muscles (Fig. 9.3). The absence of posterior rectus fascia may contribute to an inherent weakness in this area. These hernias are often interparietal, with the hernia sac dissecting posteriorly to the external oblique aponeurosis. Patients usually present with a prolonged history of intermittent lower abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction associated with a slight swelling or vanishing anterolateral mass located midway between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis. Most spigelian hernias are small (1–2 cm in diameter) and develop during 40–70 years of age, but the hernia has also been reported in younger patients. Spigelian hernias occur with almost equal frequency in males and females; they can be bilateral and associated with other ventral or inguinal hernias. Incarceration rates (often with omentum) have been reported to be as high as 20 % with these uncommon hernias [1, 4–6].

Fig. 9.3

Spigelian hernia

9.2.4 Incisional Hernias

Incisional hernias are delayed complications of abdominal surgery and occur in 0.5–13.9 % of patients. These hernias tend to occur during the first four months after surgery, a critical period for the healing of transected muscular and fascial layers of the abdominal wall. Incisional hernias are caused by patient- and surgery-related factors. The former includes conditions that may increase intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., obesity, collagen vascular diseases, a history of surgically repaired aorta, nutritional factors, ascites). Conditions that impair healing, such as collagen vascular disease in patients receiving glucocorticoid therapy and smoking, can also increase postoperative hernia formation. Surgery-related factors include the type and location of the incision. It is more common for hernias to develop after a vertical midline incision than after a transverse incision but to also develop through small laparoscopic puncture sites [4, 7, 8].

9.2.5 Eventration

Regardless of the cause, the loss of integrity of the abdominal wall reduces intra-abdominal pressure and causes serious disturbances, which is appropriately named “eventration disease” by Rives. The salient feature of this syndrome is respiratory dysfunction. A large incisional hernia produces paradoxical respiratory abdominal motion similar to the flail chest. Diaphragmatic function becomes inefficient. The diaphragm no longer contacts against the abdominal viscera and instead forces them into the hernia sac. Appraisal of respiratory function and blood gases is essential [9].

9.3 Preoperative Evaluation of Abdominal Wall Defects

The correct diagnosis of abdominal wall hernias is usually based on careful inspection and palpation; however, there are several situations in which an accurate clinical diagnosis may be difficult or impossible, such as in obese patients, those with severe abdominal pain or distention, and those with excessive scarring. Five to ten percent of abdominal wall hernias are not detectable by physical examination alone [10].

Although most abdominal wall hernias are asymptomatic, they may develop acute complications necessitating emergent surgery. In differential diagnosis it is important to keep in mind that the most challenging misdiagnosed conditions are diastasis recti and abdominal wall tumors [8].

9.3.1 Clinical Evaluation

The evaluation of abdominal wall hernias requires diligent physical examination. The anterior abdominal wall is evaluated with the patient in standing and supine positions, and Valsalva maneuver is also useful to demonstrate the site and size of a hernia. Examination should focus on the umbilicus and any incisions that are present. [1]

9.3.2 Radiological Evaluation

Imaging studies are not required in the normal workup of a hernia. The diagnosis of a hernia was made clinically, with plain radiographs or barium studies in the past. Increasingly, diagnosis is made by CT or ultrasonography.

However, cross-imaging studies may be useful in certain scenarios, as follows:

If an incarcerated or strangulated wall hernia is suspected, upright abdominal films may be obtained in clinical emergency patients to show small or large bowel obstruction; infrequently, the transition point is seen at the level of the complicated hernia.

Ultrasonography can be used in differentiating masses in the abdominal wall and allows dynamic evaluation (e.g., during Valsalva maneuver) to confirm herniation of intra-abdominal contents through a wall defect. Ultrasound may also have good specificity and a high positive predictive value for diagnosing postoperative incisional hernias [5, 11].

Multidetector-row CT (MDCT) is widely available and is fundamental in assessing patients with suspected abdominal wall hernia.

9.3.3 Signs and Symptoms

- 1.

Characteristics of asymptomatic hernias:

An obvious swelling or fullness beneath the skin at the hernia site

A heavy feeling in the abdomen that is sometimes accompanied by constipation

Discomfort in the abdomen when lifting or bending over

Aching sensation (radiates into the area of the hernia)

No true pain or tenderness upon examination

Enlarges with increasing intra-abdominal pressure and/or standing

- 2.

Characteristics of incarcerated hernias:

Painful enlargement of a previous hernia or defect

Cannot be manipulated (either spontaneously or manually) through the fascial defect

Nausea, vomiting, and symptoms of bowel obstruction (possible)

- 3.

Characteristics of strangulated hernias:

Patients have symptoms of an incarcerated hernia.

Systemic toxicity secondary to ischemic bowel is possible.

Strangulation is probable if pain and tenderness of an incarcerated hernia persist after reduction.

Suspect an alternative diagnosis in patients who have a substantial amount of pain without evidence of incarceration or strangulation.

- 4.

Characteristics of various hernia types:

Umbilical hernia – central and mid-abdominal bulge.

Epigastric hernia – small lumps along the linea alba reflecting openings through which preperitoneal fat can protrude.

Spigelian hernia – local pain and signs of obstruction from incarceration; pain increases with contraction of the abdominal musculature.

9.4 Treatment of Abdominal Wall Defects

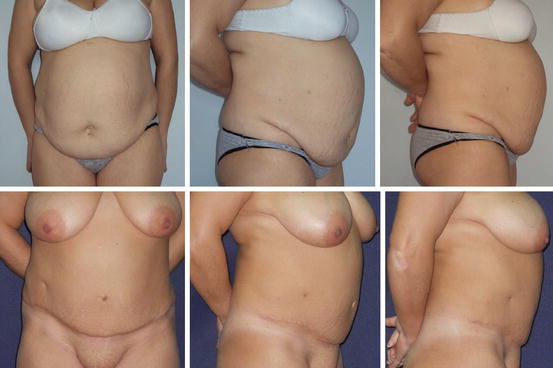

Abdominal wall hernias are either diagnosed on clinical examination or encountered intraoperatively during abdominoplasty. Skin and myofascial laxities, which are often found in overweight, postbariatric or multiparous women, are the primary indications for abdominoplasty procedure (Fig. 9.4). Abdominal wall hernias are frequently encountered problems associated with the occurrence of fascial laxity or diastasis. Both obesity and pregnancy cause increased intra-abdominal pressure, which are the main causes of rectus diastasis and anterior abdominal wall hernias [12].

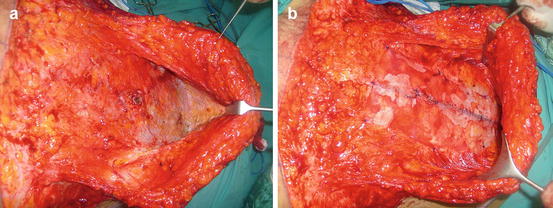

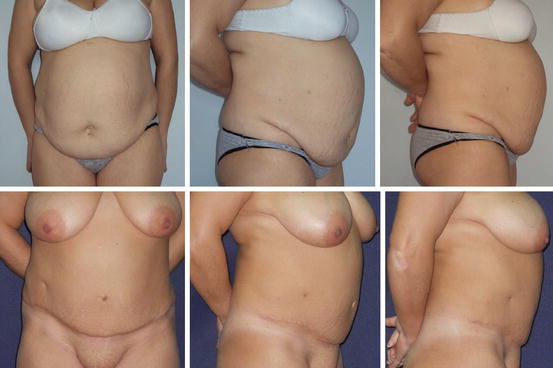

Fig. 9.4

A 44-year-old woman with severe abdominal myofascial laxity and infraumbilical panniculus. In preoperative examination, there was no sign of hernia. Incidental umbilical hernia has been determined in abdominoplasty operation. Above, preoperative views of the patient. Below, postoperative second-year view shows that there is no sign of myofascial laxity

It is not uncommon to encounter various degrees of umbilical or paraumbilical incidental hernias during abdominoplasty operations, although symptomatic umbilical hernias can be diagnosed on preoperative physical examination. Also, postbariatric patients have increased risk of incisional hernias with a reported rate of ~20 % [13].

Primary suture techniques, autologous techniques, and placement of prosthetic meshes and bioprosthetics have been described for repair of ventral abdominal hernias.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

- 1.

Primary repair

Incidental hernias during abdominoplasty operations are not rare in clinical practice, although the frequency of incidental hernia in the population and the rate of hernia in abdominoplasty patients are unknown. Usually a primary repair is enough, but first, the separation of the hernia sac from the abdominal wall ring is essential. After the sac is dissected, the peritoneum shall be examined. If intact, simple reduction of the sac is possible, but if the peritoneum is opened or injured, careful dissection and exploration of the intra-abdominal organs (omentum, intestines) is necessary. Following this exploration, the peritoneum should be closed separately. Finally the abdominal wall defect is closed by simple suture technique.

However, if the fascial defect is larger than 2–3 cm, primary repair techniques are usually inadequate. Synthetic/organic mesh materials are commonly used to bridge the fascial defect with a tension-free closure in such conditions.

- 2.

Synthetic mesh

Cumberland and Scales popularized the ideal characteristics of prosthetics [14, 15]. These properties include chemical inertness, resistance to mechanical stress, pliability, lack of physical modification by the body’s tissues, capability of being sterilized, no carcinogenic potential, no or limited inflammatory or foreign body reaction, and hypoallergenic nature. No prosthetics has been able to attain all these properties so far. In 1958, Usher et al. reported on the newly developed polypropylene mesh (Marlex) which was followed by similar plastic implantable prosthetic materials such as Mersilene and Gore-Tex [16]. This was a notable advance for surgery and allowed tension-free repairs that, when used properly, substantially diminished recurrences after hernia repair procedures. Many abdominal hernias can be repaired using synthetic mesh which lowers the hernia recurrence rates; it is today the first choice in hernia repair (Fig. 9.5). These are associated with serious complications including surgical site infection, extrusion, foreign body reaction, bowel adhesion, fistula formation, and prolonged seroma drainage that occur in ~10–15 % of cases [17, 18]. Infection is one of the most significant causes of recurrent hernia, and the risk of infection is clearly elevated with the risk factors including high body mass index (BMI), smoking status, nutritional status, steroid treatment, and the presence of comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)) in patients who have undergone synthetic mesh placement.