69 Cleft Lip Rhinoplasty

Introduction

Reconstruction of the cleft lip nasal deformity remains an ongoing challenge for the facial plastic surgeon. The deformity is a complex, threedimensional alteration in nasal anatomy with defects in all tissue layers: skin, cartilage, vestibular lining, and bone. The extent of the deformity varies with the degree of lip abnormality; it may be unilateral or bilateral and subtle or complete. 1 The sheer number of publications and techniques reported in the 20th century speaks to the difficulty of this reconstructive dilemma. 2

The goal of this chapter is to provide the reader with an understanding of the pathophysiology of the cleft lip nasal deformity, to discuss the timing of the various repairs needed, and to highlight a selection of techniques currently used to repair the deformity.

Pathophysiology of the Cleft Lip Nasal Deformity

Theory

The exact etiology of the cleft lip nasal deformity remains unknown. The two most common theories relate to intrinsic deficiencies and external pressures. Likely, the true answer is a combination of the two.

Veau proposed that the cleft lip nasal deformity is the result of agenesis of tissue within the lip and maxilla due to mesenchymal deficiency. 3 This leads to hypoplasia of the maxilla and lack of bone at the piriform margin and alar base, and causes posterolateral displacement of the piriform margin and alar base. The abnormal position of the alar base is central to the overall formation of the defect. Other authors have contended that decreased growth or hypoplasia of the lower lateral cartilage contributes to the deformity. 4 , 5 These findings have been challenged by Park et al, who made direct measurements of the completely dissected lower lateral cartilages at the time of rhinoplasty in 35 patients (ages 6 to 40). 6 They found no difference between the cleft lower lateral cartilage and the noncleft cartilage when comparing thickness at the intercrural, middle, and distal portion of the cartilage; width at the widest point; and overall length from the intercrural point to the distal end.

The extrinsic force theory holds that the abnormal insertions of ligaments and muscles lead to molding tension on the cartilage and soft tissue. Latham has postulated that the septopremaxillary ligament plays a critical role in the etiology of the unilateral cleft lip nasal defect. 7 , 8 This ligament binds the anterior septum to the premaxilla. Because the premaxilla is dissociated from the lateral maxilla by the cleft condition, these two growth centers are abnormally affected. The septopremaxillary ligament on the noncleft side provides unopposed tension on the caudal septum and columella causing deviation away from the cleft. Further, the disassociation of the growth centers leaves the lateral maxilla more posterior which creates added tension on the lower lateral cartilage. Additional extrinsic force is applied by the discontinuity and abnormal insertion of the orbicularis oris muscle. 9 , 10 On the noncleft side in the unilateral cleft deformity, the muscle inserts into the columella and provides further distraction of the columella and anterior septum away from the cleft, and on the cleft side the orbicularis oris inserts into the alar base causing additional lateral pull on the alar base. Threedimensional computed tomography scans of twelve 3-month-old children with unilateral cleft lip confirmed four consistent and statically significant findings related to the asymmetry of the nasal base. 11 All of the findings can be explained by the extrinsic force theory as detailed above: the columella is deviated to the noncleft side, the cleft alar base is more posterior than the noncleft, the noncleft alar base is further from the midline than the cleft, and the cleft piriform margin is more posterior than the noncleft. Finally, Fisher and Mann have been able to recreate the cleft lip nasal deformity in three dimensions with origami paper models. 12 Their models highlight the role that external tension places on the lower lateral cartilage and alar rim due to changes in the position of the piriform margin/alar base and columella in the development of the deformity.

These same theories can be applied to the bilateral cleft nasal deformity. The intrinsic deficiency theory allows for the absence of lip and maxilla to cause the posterior-lateral displacement of the alar base with the resulting widening of the nose but with little impact on columellar symmetry. On the other hand, the extrinsic force theory shows that the insertion of the septopremaxillary ligament is symmetric thereby causing no alteration in the anterior septum/columella unit. The insertion of the orbicularis oris musculature into the alar base bilaterally contributes to the widening of the nose and flattening of the lower lateral cartilages.

Characteristics of the Cleft Nasal Deformity

Although the pathophysiology that causes the cleft lip nasal deformity has not been completely explained, the characteristics of the deformity have been well elucidated. The deformity begins with the deficiency of tissue in the nasal base related to the maxillary hypoplasia and continues with findings related to the external pressures applied after surgical repair and during development. The following discussion will examine separately unilateral and bilateral defects and will subdivide the nose into thirds to illustrate the deformity and the repair of the deformity.

Unilateral—Lower One-Third (Table 69.1)

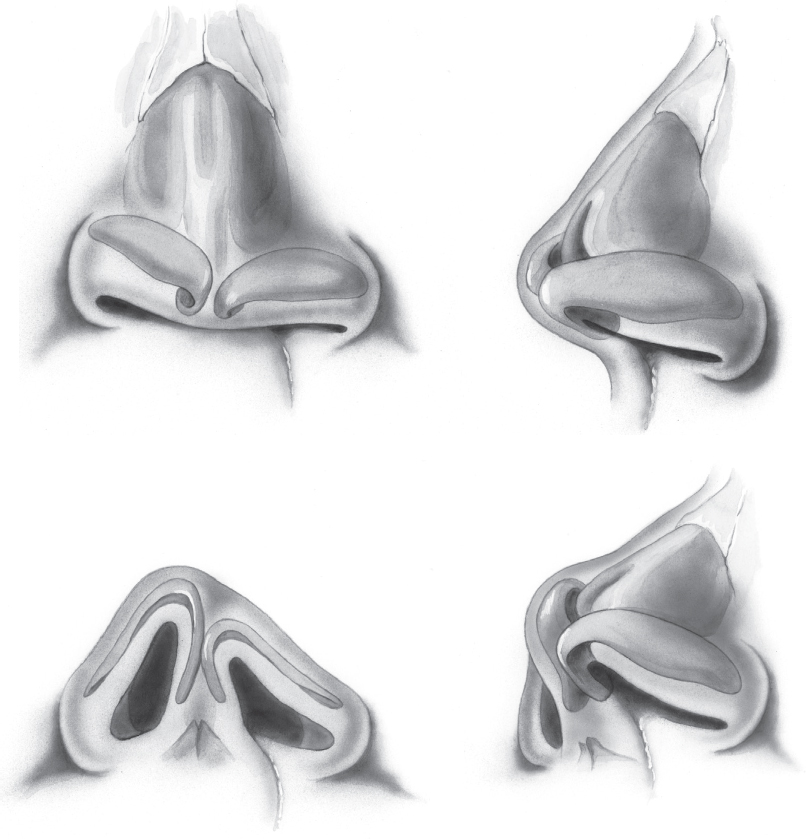

The lower one-third is the central portion of the cleft lip nasal deformity. Alterations from the noncleft nose are observed in the tip, the septum, and the external nasal valve. The nasal tip refers to the subunit composed by the alar bases, the columella, and the lower lateral cartilages. The position of both the columella and the alar base place distortional pressure on the lower lateral cartilage and influence the overall development of the deformity ( Fig. 69.1 ). The columellar complex, which is created by the medial crura and feet of the lower lateral cartilage, the caudal septum, and soft tissue, is typically deviated toward the noncleft side ( Fig. 69.2 ). Although the total length of the lower lateral cartilage is the same on the cleft and noncleft sides, the medial crus on the cleft side is foreshortened giving additional length to the lateral crus and creating a more obtuse angle to the dome. Further, the additional length leads to flattening of the dome and widening of the cleft nostril and nasal floor. The alar base is positioned posteriorly, inferiorly, and laterally when compared to the noncleft side. This changes the threedimensional configuration of the entire tip.

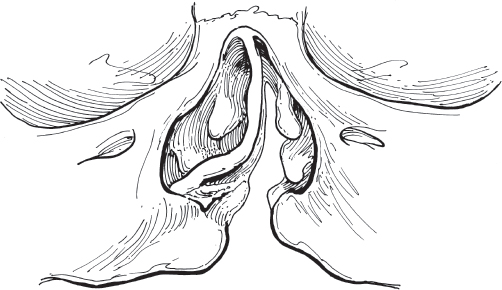

The nasal septum is deflected caudally into the noncleft nasal airway due to the unopposed pull of the orbicularis oris muscle and the septopremaxillary ligament ( Fig. 69.3 ). Further posteriorly, the lack of these attachments to the middle and posterior cartilaginous septum leads to a bowing of the septum into the cleft side airway. 4 Moreover, Crockett and Bumsted found in a study of 140 cleft septums that the bony septum was deviated into the cleft airway in 80% of cases. 13 Therefore, in the unilateral cleft condition, the nasal airway is compromised on both the cleft and noncleft side.

The external nasal valve is created by the relationship of the columella, lower lateral cartilage, nasal ala, and nasal sill. In the unilateral cleft deformity, the external nasal value is compromised by two related factors: introversion of the nasal ala and webbing of the nasal vestibule. Introversion of the cleft nasal ala is the result of posterior-inferior rotation of the lower lateral cartilage due to the distortional pressures on the cartilage from the position of the columella and alar base. 14 The introversion leads to hooding and thickening of the ala; it also contributes along with surgical scarring to webbing of the nasal vestibule. An oblique fold is formed by the posterolateral displacement of the piriform margin and the introversion of the lower lateral cartilage. This bulk influences airflow and alters the relationship of the upper and lower lateral cartilages.

Unilateral—Middle One-Third

The middle one-third of the nasal deformity can be characterized by interrelated changes to the upper lateral cartilages and to the internal nasal valve. On the cleft side, there is limited attachment of the upper and lower cartilage and a side-toside relationship rather than the more typical overlap seen on the noncleft side. 13 Both of these factors lead to decreased support of the upper lateral cartilage and collapse of the upper lateral cartilage with deep inspiration. The internal nasal valve is formed by the relationship of the upper lateral cartilage, the nasal septum, and the inferior turbinate. In the cleft lip nasal deformity, the septum is bowed into the cleft side at the internal nasal value, and the upper lateral cartilage support is weak causing the cartilage to bow or collapse with respiration. Therefore, the internal nasal valve can significantly limit the nasal airway on the cleft side.

Unilateral—Upper One-Third

Although there is no classic deformity to this portion of the nose in the cleft lip nasal deformity, the osseous pyramid is typically reduced in width at the time of definitive rhinoplasty to enhance the overall appearance of the nose.

Bilateral—Lower One-Third (Table 69.2)

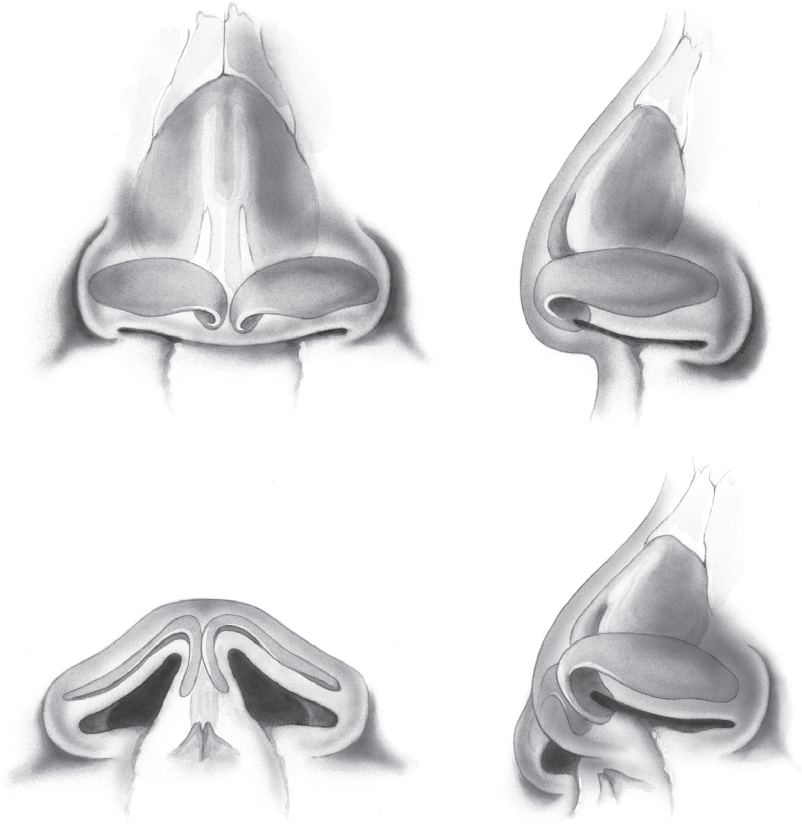

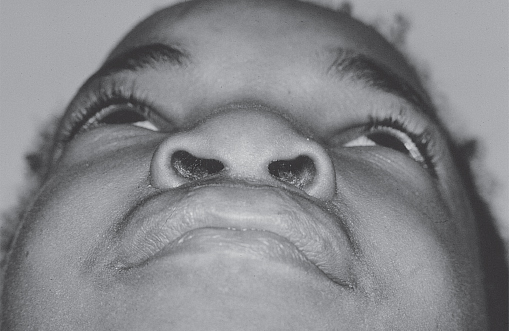

Similar to the unilateral deformity, the primary characteristics of the bilateral deformity revolve around the lower one-third of the nose ( Fig. 69.4 ). The nasal tip is typically in the midline in the bilateral complete deformity. If one side of the lip is more involved than the other, the short columella is typically deviated toward the less involved side, pulling the tip in that direction ( Fig. 69.5 ). The lower lateral cartilages demonstrate short medial crura and long lateral crura. The domes of the lower lateral crura are splayed contributing to a poorly defined, frequently bifid tip ( Fig. 69.6 ). The angle at the dome is obtuse. The alar bases are posterior, lateral, and inferior giving rise to flaring of the base and widening of the nostril. The tension on the lower lateral cartilage leads to introversion and webbing of the vestibular floor. The septum is in the midline in the complete bilateral deformity and deviated caudally toward the less involved side if an asymmetry exists.

Bilateral—Middle One-Third

The middle one-third is analogous to the unilateral deformity with poor support to the upper lateral cartilage leading to bowing and possible collapse of the upper lateral cartilage with deep inspiration. However, because the septum is typically in the midline, the compromise of the internal nasal valve is often not as significant.

Bilateral—Upper One-Third

The upper one-third is typically not involved in the bilateral nasal deformity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree