42 Rhinoplasty in the Patient of African Descent

Introduction

The demographics of patients requesting aesthetic rhinoplasty has evolved considerably over the past three decades. Presently, the non-Caucasian demographic accounts for approximately 33% of the U.S. population. Conservative estimates indicate that this group, which includes Africans, Asians, and Hispanics, is among the most rapidly growing group within America and will constitute about 54% of the population by 2050. 1 This period has seen a significant increase in the number of patients of African descent requesting rhinoplasty. While this increase may reflect an increased awareness of rhinoplasty and a positive shift in economics and attitude toward elective surgeries, the general theme is that these patients desire an aesthetically pleasing appearance that preserves their ethnicity, while embracing facial harmony.

The aesthetic result desired by patients seeking nasal reshaping surgery is strongly influenced by one’s perception of beauty, which is influenced by a multitude of factors including race, ethnicity, and culture. Due to the diverse ethnic nature of most communities, the perception of beauty is not homogeneous. Beauty is a perception of good balance, symmetry, harmony, and features that are generally pleasing to the eye. Many attempts have been made to standardize what is and is not beautiful by establishing ethnic norms. Surgeons commonly attempt to achieve these ideal norms, which unfortunately may not necessarily be considered beautiful by the individual patient. The rhinoplasty surgeon must be aware of and embrace the ethnic, cultural, and anatomical features unique to this population. A comprehensive understanding of the facial features and beauty trends in patients of African descent is essential for appropriate nasal analysis when planning rhinoplasty.

Race is an objective term that defines people of the same heritage who share similar physical attributes, while ethnicity is a concept that is self-assigned and more subjective. Culture refers to a set of patterned beliefs or values that may or may not take race or ethnicity into account. 2 Members of the same race may not necessarily share ethnic identities or the same concepts of beauty. Since people from similar ethnic backgrounds may have very different cultural values, it is important to note that cultural forces play an important role in how individuals perceive beauty. These concepts of race, ethnicity, and culture in addition to the complex interplay among them should be explored when evaluating patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds who are seeking cosmetic rhinoplasty.

The concepts of preserving or altering racially defining features are important to consider when evaluating patients of African descent. In addition to the desire to improve aesthetic appearance, harmony, and facial balance, most patients of African descent also have a strong desire to achieve outcomes that preserve racially and ethnically concordant features. Racial transformation, in contrast, refers to the transformation of a patient’s features in order to obtain a more Westernized or otherwise racially discordant appearance. Patients who desire racially transforming nasal changes should be educated about the potential risks of this objective, and these requests should generally be discouraged.

Although the desired outcomes of patients of African descent seeking rhinoplasty cannot be generalized, there are common trends including achieving a defined dorsum, improved tip definition, and a narrowed midvault and alar base. In this chapter, we outline an approach to systematically analyze and reshape noses in patients of African descent, in a manner that is ethnically congruent.

Anatomy

The nose is composed of the soft tissue envelope and cartilaginous and bony framework lined internally by respiratory mucosa. In most African noses, the soft tissue envelope of the nasal tip is often thicker when compared to that of the Caucasian nose. This thick nasal tip skin often effaces the structure of the underlying cartilages resulting in a bulbous and illdefined nasal tip. The skin can be thick, sebaceous, and inelastic with a generous subcutaneous fibrofatty layer (2 to 4 mm thick).

The supportive nasal framework consists of the nasal bones, the upper lateral cartilages (ULCs), the lower lateral cartilages (LLCs), and the premaxilla. The nasal bones articulate with the nasal processes of the frontal bone and maxilla superiorly and laterally. 3 An obtuse angular relationship between the nasal bones at the dorsum will result in an illdefined dorsum and broad midnasal vault, both of which are common complaints of patients of African descent seeking rhinoplasty. Short nasal bones, a common feature in the African nose, risks midvault collapse following aggressive osteotomies. 4

The ULCs articulate cephalically with the undersurface of the nasal bones and caudally with the LLCs in the scroll area. The ULCs provide support to the midnasal vault and together with the nasal bones determine the width of the nasal bridge and the definition of the nasal dorsum. The ULCs are supported by the underlying quadrangular cartilage of the nasal septum with which they are in continuity. The quadrangular septal cartilage is a prime source of grafting material during rhinoplasty but may be inadequate for cartilage harvest in the patient of African descent; thus, alternative sources for grafting material should be considered. The septum ends caudally at the anterior septal angle and plays an important role in supporting the nasal tip.

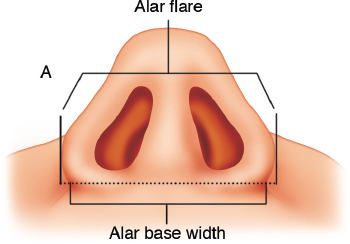

The LLCs play a dominant role in providing nasal tip support. Each LLC consists of a medial, middle, and lateral crus. The size, contour, and orientation of the paired LLCs determine the width and definition of the nasal tip. When dissected free of the surrounding soft tissue, the LLC is seen as a threedimensional structure changing orientation in multiple planes to give structure and shape to the nasal tip. The transition from the medial to the lateral crus of the LLC defines the intradomal angle. A broad intradomal angle contributes to a wide bulbousappearing nasal tip with poor definition. The interdomal angle is the angle that is created between the two intermediate segments of the LLC; this interdomal angle partly dictates the distance between the nasal tip–defining points. It is the reflection of the contours of the LLC through the overlying skin that determines the definition and aesthetic appearance of the nasal tip. The nasal alar is devoid of any cartilaginous support caudal to the lateral crus of the LLC. Thus, the shape and resilience on the nostril along the alar margin depends greatly on the rigidity of the soft tissue in the region of the ala ( Fig. 42.1 ). On base view, the nostril takes on a pear-like shape and can vary widely in size. The nostril shape and size are determined laterally by the alar margin, medially by the columella, inferiorly by the nasal sill, and superiorly by the soft triangle. Laterally, the alar rims should transition smoothly from the nasal tip to the alar facial grooves. A significant degree of flare along the alar margin is common in individuals complaining of wide nostrils. The alar base width is distinct from alar flare and is measured as the distance between the two alar-facial transition points ( Fig. 42.2 ). The appropriate alar base width is determined from patient to patient based on the aesthetic proportions of the entire face.

Nasal tip support is complex and based upon relationships between several adjacent structures. These include the LLCs, fibrous attachments between the ULCs and LLCs, suspensory ligaments overlying the crura and anterior septal angle, the abutment of the LLCs with the pyriform aperture, the nasal septum, and the anterior nasal spine. 5

Preserving nasal function is paramount when considering rhinoplasty procedures. The nasal valves are critical to nasal function and play a critical role in regulating nasal airflow. The external nasal valve is composed of the caudal septum, columella and premaxilla medially, and the alar lobule, ala, and dilator muscles laterally. 6 The internal nasal valve angle formed by the junction of the septum and the caudal aspect of the ULCs is the narrowest portion of the nasal airway and accounts for the majority of the upper airway resistance. 6 Whereas the internal valve angle should be between 10 and 15 degrees for adequate airflow to occur during inspiration in Caucasian noses, it is generally wider in the African nose. The nasal valve area, described by the area bound by the septum, the caudal end of the ULC, and the head of the inferior turbinate, is believed to have a greater impact on upper airway resistance in patients of African descent. 7

There are several descriptions in the literature as to the distinctions between the Caucasian nose and the African nose. Among them, however, are a number of myths. Many variations in this community stem from the triethnic background of African American, 8 which is a reflection of the same variations seen in Central and South America within the patients of African descent. On the continent of Africa itself, there is an appreciable variation in facial features and nasal anatomy based on the various ethnic groups and regions. This is attributed to the inherent racial differences as well as interracial mixing from other continents that have occurred for centuries as seen by a strong East Indian influence in East and South Africa as well as Arab influence in Northern and Eastern Africa. Anatomical variations in Caucasians and patients of African descent are summarized here.

Nasal Pyramid

When compared with the Caucasian nose, the African nose has often been described as flat, wide, and underprojected. There is generally a deepened nasofrontal angle and a low radix. The nasal bones generally lack projection of the ascending process of the maxilla, which contributes to the low and widened nasal base. 9 , 10 , 11 It is for this reason that dorsal augmentation with grafts and implants is commonly performed in African American rhinoplasty.

Alar Cartilages

Alar cartilages in the African patient are often thought to be thin and weak and lack enough strength to support the nasal tip, which typically contains thick fibrofatty sebaceous skin. On the contrary, anatomical studies by Rohrich 11 revealed that the African patients had alar cartilages that were similar in size to the Caucasian alar cartilages. Ofodile and James 12 reported similar findings, though there was variation along the previously mentioned triethnic lines. As such, cadavers with the Africantype nose had narrower alar cartilage compared with the Afro-Indian and Afro-Caucasian type noses. The medial and lateral projections of the alar cartilages are not shorter and weaker than in Caucasians as previously thought but are quite developed. The premaxilla and the anterior nasal spine in the African patient with African features are typically not as prominent in comparison to the Caucasian patient. The angle between the medial and lateral crura is obtuse, and the space is filled with a relative abundance of fat and skin. The columella is short and rounded and often hidden on the profile view by heavy overlying alar rims. These differences contribute to an acute nasal labial angle and diminished nasal tip support. 13

Nasal Analysis

Analyzing noses of patients of African descent for rhinoplasty immediately reveals a broad diversity in shape and skin thickness that makes it difficult to use strict anthropometric standards as a guide. Though anthropometric data have been described, it is important that surgeons interested in rhinoplasty in this group develop a systematic approach of analyzing each nose based on concepts of the beautiful African nose. 14 One way to develop this concept is to closely look at noses of individuals of African descent who make “the most beautiful black women list” published by contemporary popular magazines. Noses of these women may be examined for trends in radix projection, profile shape, dorsal and tip projection, tip width, nostril shape, degree of alar flare, and base width. This exercise trains the surgeon’s eyes to see the African nose in context of the entire face instead of nasal angles and ratios.

The input of patients is very useful when analyzing noses of patients of African descent. One simple approach the authors use to gain insight into the aesthetic taste of individual patients is to ask what they like and dislike about their noses. While patients are often quick to list what they do not like about their noses, they usually have difficulty identifying features they like. Identifying features that are desirable helps set a reference point when designing the shape and form of the nose.

One approach to systematically analyze the African nose begins with the skin. First, determine the thickness of the nasal skin anticipating how it will respond to dissection, scar formation, and secondary contouring. Palpating and pinching the nasal tip skin gives valuable information about what it will take to achieve definition. Next, evaluate the starting point of the nose at the radix. The radix should be analyzed for its depth and projection above the medial canthi, relation to eyelids, and degree of definition by its ability to reflect light. The radix is a common area of concern for patients of African descent seeking rhinoplasty. Patients often describe their radix as flat. As a guide, the radix in most patients of African descent is not far projected above the medial canthi and takes off in line with the pupil or lid margin in primary gaze. An overly projected radix, starting off higher than the lid margin, may cast a shadow over the eyes, making them appear sunken in and giving an unnatural appearance. Next, determine the tip projection and the desired changes needed. The nasal tip in patients of African descent is generally not as projected as in Caucasian patients. Extreme alteration in nasal tip projection may appear uncharacteristic and unnatural. Once the radix and tip projection have been determined, the desired profile may be determined by joining these two points and incorporating a dip in the supra tip area if desirable. The nose can then be analyzed on frontal view. The frontal view is what patients most often use to critically judge their rhinoplasty results. On frontal view, the nose may be divided into upper, middle, and lower thirds corresponding anatomically to the nasal bones, ULCs, and LLCs, respectively. The upper third is the region between the eyes in the region of the radix. As the nasal bones are palpated, they should be analyzed for length. Short nasal bones should raise caution when considering osteotomies. The width of the midnasal vault should be determined and the need for midvault narrowing considered. The lower third of the nose is analyzed for tip definition, alar contour, width, and dynamic changes when smiling. Tip definition should not be considered synonymous with tip width. The shape, strength, and contour of the tip cartilages as they influence the function and aesthetics of the tip are evaluated. If the tip is bulbous, the contribution from the skin and tip cartilage contour should be determined. Correcting bulbous tips resulting predominantly from thick skin is more challenging than that resulting from broad LLCs and wide intradomal angles.

Analysis of the basal view gives vital information about the alar lobule, degree of alar flare, alar–facial transition, nostril shape, size and symmetry, upper lip length, and transition at the nasolabial point. Most patients of African descent have some degree of alar flare, which should be preserved even after nostril reduction. Using cotton-tipped applicators gently placed in the nostrils, the nasal tip can be projected to gain a sense of the secondary changes in alar flare that can occur after surgical manipulation.

A wide alar base is a common reason patients of African descent seek rhinoplasty. The alar base width is commonly analyzed in the context of midfacial width and intercanthal distance. The alar base is considered wide when the alar is positioned lateral to the medial canthi in Caucasians. In patients of African descent, we find the caruncles instead of the medial canthi to be a better reference point.

The alar base should also be evaluated for dynamic changes. A common complaint is the “spreading” of the nasal base and complete loss or blunting of nasal definition when smiling. Widening of the nasal base with a smile is an inevitable effect of contracting facial muscles on the nose. Providing more support to the nasal tip, alar base, and midvault counters the forces of contracting facial muscles and minimizes the degree of blunting when smiling.

The frontal view should be analyzed for overall definition, proportion, and size. The defined tip reflects light and its outlines can be subtly differentiated from the dorsum and alar lobules. A defined tip is not necessarily pointy, projected, or isolated but rather reflects a visual contrast of highlighted tipdefining points surrounded by subtle shadow areas. The width of the nasal tip may be equal or slightly wider than the dorsal width determined by the brow tip aesthetic lines. We have found the width of Cupid’s bow on the upper lip is a good measure for an appropriate tip width in patients of African descent.

A defined nasal bridge is not necessarily a projected bridge but rather one that has a clear contrast between the sidewalls and the dorsum. It is not uncommon to hear from patients that they can achieve a more defined nasal appearance using makeup.

As in all rhinoplasties, intranasal examination should be performed in all patients to determine the patency and support of the nasal airway, availability of cartilage for grafting purposes, and the presence of any pathology that may need to be addressed.

Patient’s Desires and Goals of Rhinoplasty

In general, patients of African descent considering rhinoplasty desire some form of nasal refinement, without loss of their ethnic identity. As such, the term “nasal refinement” is preferred, as it refers to operative changes made to reshape the nose into a more pleasant form. When considering rhinoplasty in Caucasian patients, do we as surgeons approach the nose with intention to change the general ethnicity of the patient, or do we strive for a esthetically pleasing and facially harmonious results? Most surgeons will attest to the latter. It is with this philosophy in mind that patients of other ethnic groups should be approached where indeed facial harmony, with preservation of one’s ethnic identity and nasal function, is paramount. Today, with interracial mixing in what is America’s melting pot, we find a blend of features that may not fit into our traditional models; as such, the need for analysis and desire for facial harmony holds even more true. The surgeon has the challenge of formulating an operative plan that optimally addresses these patients’ desires. Achieving this goal hinges upon an understanding of the nasal anatomy of the patients of African descent as well as the critical differences that affect the operative technique of choice. Rohrich and Muzaffar 15 succinctly summarize five goals in African American rhinoplasty:

Maintaining nasal-facial harmony and balance

A narrower, straight dorsum

Enhanced tip projection and definition

Slight alar flaring

Narrower interalar distance

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree