41 East Asian Rhinoplasty

Introduction

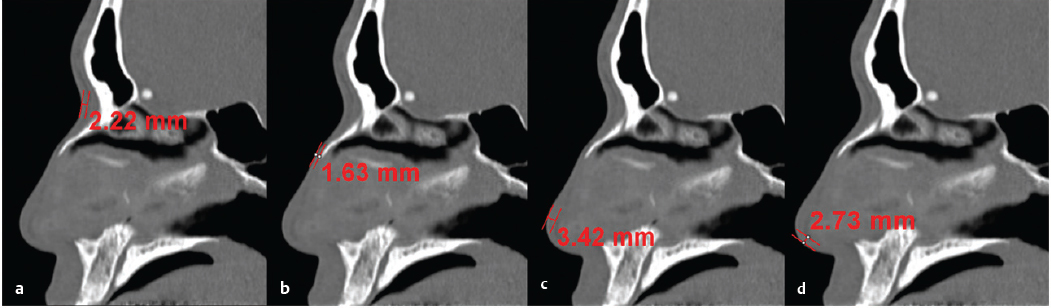

East Asia encompasses China, Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. Also, there are many Chinese descendants in Southeast Asian countries including the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam. The typical East Asian nose tends to have thicker nasal skin than Caucasian noses, with abundant subcutaneous soft tissue. In author’s research using computed tomography (CT) scans on the thickness of the nose in Koreans, the mean nasal skin thickness was 3.3 mm for nasion, 2.4 mm for rhinion, 2.9 mm for nasal tip, and 2.3 mm for columella ( Fig. 41.1 ). In the author’s study, thick skin at the nasal tip and columella was associated with poor surgical outcomes, suggesting that regional skin thickness is an important prognostic factor for tip surgery success. 1 The tip of the East Asian nose is usually low and the lower lateral cartilages are small and weak. The nasal bones are poorly developed and thick, thus manifesting low radix. The average nasal length to nasal tip projection to dorsal height to radix height ratio of the Caucasian nose has been shown to be 2:1:1:0.75. 2 However, in the author’s study, young Koreans had a nasal length to nasal tip projection to dorsal height to radix height ratio of 2:0.97:0.61:0.28. 2 These data indicate that East Asians had lower dorsal and radix heights. It was also found that East Asians have a more acute nasolabial angle than Caucasians, but a similar nasofrontal angle. The septal cartilage is thin and small. Therefore, the size and the quantity of harvestable septal cartilage may be inadequate for complete rhinoplasty procedures, indicating the higher possibility of harvesting grafts from other sites. 3

Dorsal Augmentation

General Consideration

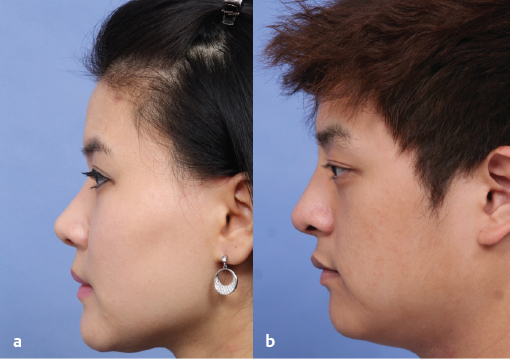

Dorsal augmentation is the most commonly addressed issue in East Asian rhinoplasty and also the most common reason for revision surgery. During dorsal augmentation procedure, it is important to set an ideal nasal starting point corresponding to the cephalic end of the implant. The cephalic end of the implant is best located around the horizontal midpupillary line or just above for women, and between the upper eyelash and eyelid crease for men ( Fig. 41.2 ). The thickness of the patient’s skin must be taken into consideration. If excessive dorsal augmentation is performed on a patient whose skin is too thin, there is a risk of implant visibility through the skin or an extrusion of the implant. Conversely, too thick skin can decrease the effect of dorsal augmentation. Therefore, in patients with thin skin, it is preferable to use soft implants such as Gore-Tex (W. L. Gore & Associates) or autologous tissues such as morselized cartilage rather than silicone. In patients with thick skin, a relatively solid material such as silicone, reinforced Gore-Tex, or costal cartilage can be used without causing significant problems. In particular, when using implants with a certain level of hardness, such as silicone or costal cartilage, the base of the implant should be trimmed well so that it conforms to the contour of the nasal dorsum. Otherwise, an up and down motion by palpation or deviation of the implant can occur, leading to implant visibility through the skin.

Implant Material

Various implant materials have been used for dorsal augmentation. Materials used in rhinoplasty can be divided largely between biologic tissues (autologous and homologous tissue) and alloplastic materials. In rhinoplasty for Caucasians, use of an alloplastic implant, especially silicone, on the nasal dorsum has generally been condemned. However, in East Asian rhinoplasty, alloplastic implants still play a role due to the differing anatomical characteristics of Asians, such as thick skin and poorly developed cartilaginous framework, compared with Caucasians.

Alloplastic implants generally need to be biocompatible, nontoxic, chemically safe, and nonimmunogenic. In addition, they must not induce infection, cancer, or produce toxic substances within the body. Additionally, during recovery, these implants should maintain their original size, shape, and hardness. At present, the most commonly used alloplastic implants that meet these conditions are silicone, Gore-Tex, and Medpor (Stryker). There is no single ideal implant or graft for dorsal augmentation. Each and every material has its own merits and drawbacks. 4 Thus, when surgeons choose a dorsal implant material, they should consider the material characteristics and anatomical characteristics of the patient, and their own level of expertise in using each material. Based on my own experience, delayed inflammations and infections that are exhibited a long time after surgery are more common in alloplastic implants, and if not treated adequately, can cause serious deformations. Longterm followup of rhinoplasty patients demonstrates that aesthetic complications are much more frequent in biologic implants. The reasons are visibility of the dorsal cartilage implant, absorption or deformation, and absorption occurring in cases using fascia or dermofat.

Inserting a foreign material between the nasal skin soft tissue envelope and nasal skeleton is by definition a procedure bound to involve complications. Therefore, the surgeon must adequately explain these risks to patients and be able to handle problems appropriately when they occur.

Silicone

Nasal dorsal augmentation with a prefabricated silicone implant is the most popular rhinoplasty procedure in Eastern Asia. The easy availability of readymade products makes application convenient, and the relative hardness of silicone makes it suitable for fashioning the desired nasal shape for Asians with a moderate to thick skin. 5 The prefabricated products can be divided largely into L- and I-shaped implants. Some surgeons favor an L-shaped or a variation of I-shaped silicone (covering the nasal tip) capable of covering from the radix all the way down to the nasal tip. 6 However, because the nasal tip area is an area that is always exposed to exterior stimulation, the use of L-shaped silicone carries a higher risk of extrusion, regardless of the thickness of nasal subcutaneous tissue in Asians. Thus, a placement of an I-shaped implant at the nasal dorsum area and tip plasty using an autologous material (septal cartilage, conchal cartilage) at the nasal tip area is preferable surgical method. In trimming the silicone, it should preferably be about 3.5–4 cm long and about 8 mm wide and the edge should be as thin as possible. When designing the silicone implant, natural convexity of the underlying nasal skeleton should be considered. Therefore, it is advisable to thin the implant contacting over the rhinion area. The caudal end of the silicone implant should not be in direct contact with tip skin. Thus, placement of stacked tip onlay graft on the dome area, which is in direct contact with the tip skin, is frequently a combined procedure ( Fig. 41.3 ). Revision rhinoplasty after silicone implants may be needed for implant deviation, floating, displacement, extrusion, impending extrusion, and infection ( Fig. 41.4 ). 7 Although infection is one of the most dreadful complications of silicone implants, early infections can be prevented by the use of aseptic techniques and prophylactic antibiotics. Infection can also be treated by implant removal, antibiotic administration, and delayed re-augmentation. Extrusion of the implant can occur through the nasal skin or mucosa, with tension over the implant being the most common cause of extrusion.

Gore-Tex ( Video 41.1)

Gore-Tex (expanded polytetrafluoroethylene [ePTFE]), next to silicone, is one of the most widely used alloplastic implant in East Asian noses. Gore-Tex implants have micropores that induce the surrounding tissue to grow inward through the pore, and have the advantages of increased stability and lower incidence of capsule formation. In addition, the risk of extrusion is lower with Gore-Tex than with silicone. The soft texture of Gore-Tex reduces patient discomfort, and the occurrence of unnatural visible implant contours through the skin is relatively uncommon, compared with silicone implant. 4

Since the thickness of commonly used ePTFE is usually 1–2 mm, multiple sheets should be stacked to get considerable increase in dorsal heights. The convenient part about using sheet implants is that augmentation levels can be adjusted for each region easily, even for patients with focal prominence or depression in dorsal height. If the surgeon conducts partial augmentations in regions such as radix and supratip nasal dorsum, using multiple layers for such regions can achieve getting the desired dorsal line (differential augmentation) ( Fig. 41.5 ). One thing to keep in mind is that when using multiple layers of Gore-Tex, the upper sheet should be carved narrower than the lower sheets to create a natural-looking nasal shape. Therefore, when designing a thick augmentation material of over 4–6 mm height, design the bottom sheet wide enough to make the whole cross-section a rhomboid/diamond shape.

When using Gore-Tex, sufficient beveling of the sheet’s margins is essential, especially for sheets of over 2 mm in thickness. If not beveled enough, the implant’s margins can be felt through the skin after surgery. When using ePTFE sheets, especially when stacking multiple layers, it is better to make a slightly wider pocket than the size required when using silicone, because a narrow pocket could fold or wrinkle the implant’s margins during insertion. After preparing the nasal dorsum fully, copious irrigation of the pocket right before implant insertion helps reduce infection.

When performing rhinoplasty via external approach, inserting the implant right in the midline position is not a difficult procedure, but the midline placement of the implant may be little more difficult through the endonasal rhinoplasty approach.

One notable disadvantage of Gore-Tex is that it decreases in volume after insertion. 8 In addition, it is more difficult to remove a Gore-Tex implant from the nasal dorsum than a silicone implant. Delayed inflammation is a serious complication due to the use of this material ( Fig. 41.6 ). One must be cautious when using Gore-Tex in the presence of inflammation within the nasal cavity (sinusitis, vestibulitis, and active acne). Before handling the Gore-Tex, surgical personnel should wash their gloves to remove powder or other foreign substances. It has been reported that infection rate in primary surgery is 1.3%, while infection rate in secondary surgery is 4.3–5.4%. 9 , 10

Autologous Cartilage

The advantage of autologous material for the dorsal augmentation of the nose cannot be questioned as these implants are well tolerated and carry the least risk of infection. However, if any autologous tissue other than septal cartilage is selected, the additional operative time required to harvest the graft and donor site morbidity become limiting factors. Common autologous tissues used for dorsal augmentation include septal cartilage, conchal cartilage, costal cartilage, fascia, and dermofat. As it is easy to harvest and shape the septal cartilage, it can be used to moderately elevate the nasal dorsum, to camouflage a partial concavity on the dorsum, and for nasal tip surgery. Since Asian patients have relatively small noses, a major limitation in the use of septal cartilage for dorsal augmentation is its limited availability; the amount of harvested septal cartilage is not always enough for simultaneous use in multiple grafting procedures. 3 Furthermore, it is often difficult to carve the cartilage to fit nicely onto the dorsum without irregularity.

Conchal cartilage, unlike septal cartilage, has an intrinsic curvature that hampers its routine use in a dorsal augmentation in its original shape. Rather, in surgery on Asian noses, conchal cartilage is more frequently used for nasal tip surgery, to camouflage a partial concavity, or to cover the tip of the silicone implant to prevent extrusion. In addition, the conchal cartilage is frequently too small to yield a cartilage piece suitable for one-piece dorsal augmentation. To overcome the intrinsic curvature and limited size of the conchal cartilage, suturing and layering of the cartilage into a multilaminar structure has been suggested. However, even with this technique, the intrinsic irregularity of conchal cartilage becomes noticeable some time after surgery. Another method to evade this problem is the use of conchal cartilage in diced form wrapped with fascia, and this has gained wide acceptance as an ideal dorsal augmentation technique.

Although costal cartilage is difficult to harvest and is associated with more serious donor site morbidity such as pneumothorax, as well as the problem of warping, it is the most useful as autologous cartilage for a thick-skinned primary case who requires substantial augmentation or in revision cases who have experienced complications with alloplastic implants ( Fig. 41.7 ). Although strongly advocated by some surgeons for routine use during the primary Asian rhinoplasty, 11 except for only a few highly experienced rhinoplasty surgeons, most rhinoplasty surgeons have difficulty using this cartilage at the nasal dorsum to form an aesthetically pleasing nose. In the author’s experience, overall complication rates and revision rates of rhinoplasty using autologous costal cartilage are much higher than those of rhinoplasty using other graft materials. The overall complication rate was 17.6%, including an infection rate of 8.4%. Warping, graft visibility, and unnatural looking noses are common complications of augmentation using costal cartilage ( Fig. 41.8 ). 12 Therefore, inexperienced rhinoplasty surgeons should use costal cartilage with great caution.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree