Abstract

This chapter examines tuberous breast deformities. Beginning with etiopathology at patient presentation, the authors guide the reader through each anatomic component and discuss how to properly contour each anomaly and/or deformity encountered. Discussion of surgical treatment starts with the incision and proceeds to the correction of anomalies/deformities. Remedial techniques proposed include customized dermoglandular flaps, glandular scoring incisions, and gland unfurling, which the authors consider the best option and thus cover in detail. Drawings and photographs greatly assist in illustrating the text. The comprehensiveness of the chapter is seen in the space devoted to other techniques, such as tissue expansion and fat grafting. Paragraphs on postoperative care, outcomes, and complications conclude the study.

37 Tuberous Deformity of the Breast (Breast Implantation Base Constriction)

37.1 Goals and Objectives

Understand the basics of tuberous breast deformity.

Define the key findings of the varying anomalies and appreciate the benefits of addressing each anatomic component for proper contouring.

Know the evidence-based perioperative care to maximize patient safety and quality outcomes.

37.2 Patient Presentation

The tuberous breast, which might be better termed “breast implantation breast constriction (BIBC),” is a congenital anomaly that only becomes apparent at the time of breast development. Although rare, it may also occur in males as a form of gynaecomastia. 1 Several other terms to describe the anomaly have been used in the English literature that should likewise be avoided, including tubular breast, constricted breast, doughnut breast, snoopy deformity, nipple breast, breast with narrow base and dome nipple. In severe cases, patients can suffer from social anxiety, depression, peer rejection, psychosexual dysfunction, and low self-esteem. 2 With no exact etiology yet clarified, it is accepted that it has an embryological origin although no family incidence or noxious fetal stimulus has been recognized. Its true incidence is unknown because its clinical definition has not yet been clearly stated.

37.2.1 Etiopathology

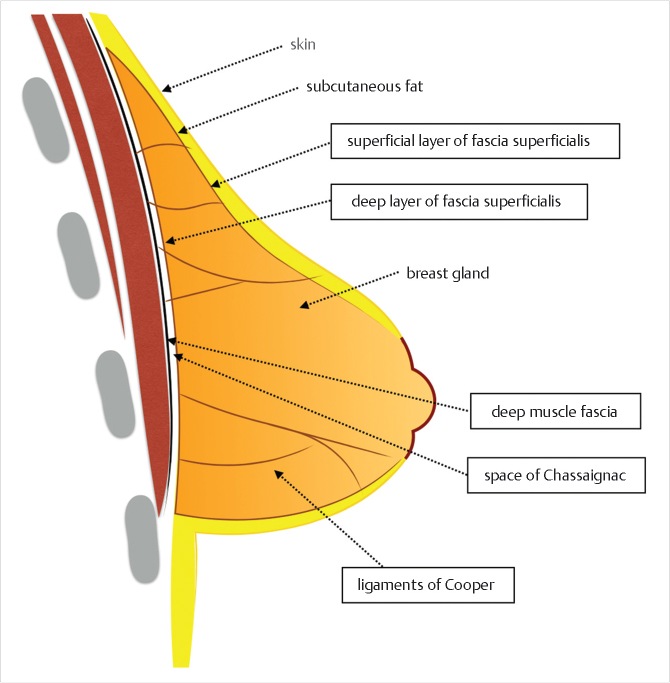

In order to understand the tuberous breast and appropriate treatment, an appreciation of breast fascial development and anatomy is mandatory. During gestation, the developing ectodermal breast bud penetrates the underlying mesenchyme and becomes enclosed within the superficial and the deep layers of the fascia superficialis that is continuous with the superficial abdominal fascia of Camper. 3 , 4 The superficial layer covers the breast parenchyma while the deep layer forms its posterior boundary and is separated from the underlying muscle fascia (pectoralis major and serratus anterior) by the loose areolar space of Chassaignac. 5 Vertical fibrous attachments (suspensory ligaments of Cooper) extend from the deep muscle fascia and the deep fascia of the fascia superficialis through the breast parenchyma and join the superficial fascia and the dermis. The superficial layer of the fascia superficialis, however, is absent in the area underneath the nipple-areola complex (NAC) (Fig. 37‑1). 5 , 6 , 7 During puberty, ovarian hormonal secretions determine breast development. Breast glandular structures (acini and galactophorous ducts) are under extreme hormonal influences (estradiol and progesterone) and it has been demonstrated that a harmonious growth and final glandular volume and shape are greatly influenced by the delicate balance of these two hormones.

Classically, a congenital fascial anomaly has been considered the underlying cause and two different theories have been proposed. First, the fibrous annular constriction band theory, proposed by Mandrekas et al, suggests that abnormal development of the fascia superficialis leads to restricted growth of the breast in one or more directions at the time of puberty. 6 , 7 The band is composed of dense fibrous tissue made of large concentrations of collagen and elastic fibers arranged longitudinally which do not allow the developing parenchyma to expand during puberty. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 The resultant narrow glandular base favors preferential vertical growth toward the areola anteriorly where the fascial layer is naturally attenuated if not almost nonexistent, hence causing it to become oversized and protuberant and creating the tuberous shape and areolar widening. 12 , 13 , 14 Existence of this periareolar constriction band has been demonstrated histologically. 6 , 7 A second theory, less popular and proposed by Pacifico et al and Costagliola et al, suggests that the causative aberrancy is a weakening within the NAC dermis and fascia, and not a constriction band at the breast base, which leads to herniation of tissue through the NAC as the breast develops. 13 , 15 Despite the recurrent descriptions of a fascial origin, it has been acknowledged that these fascial theories are pure speculations and Klinger et al, in 2011, have demonstrated histological evidence of a disorder in collagen deposition involving all of the stromal components (derma, gland, adipose tissue, and fascia) in patients with tuberous breasts versus normal breasts. 16

For one reason or another, a glandular growth restriction exists, mainly at the lower quadrants. As a consequence, the inframammary fold (IMF) ascends and the gland herniates through the areola, where the fascia superficialis is naturally nearly absent. Depending on the amount of gland, the growth restriction and the patient’s areolar characteristics, the areolar size and protrusion will be more or less evident and a continuous spectrum of anomalies can be found, sharing all the them, in varying degree, the following key features:

Breast gland constriction (more severe at the lower quadrants).

Ascended inframammary fold (as a consequence of breast growth restriction).

Areolar enlargement and protrusion.

37.3 Classification

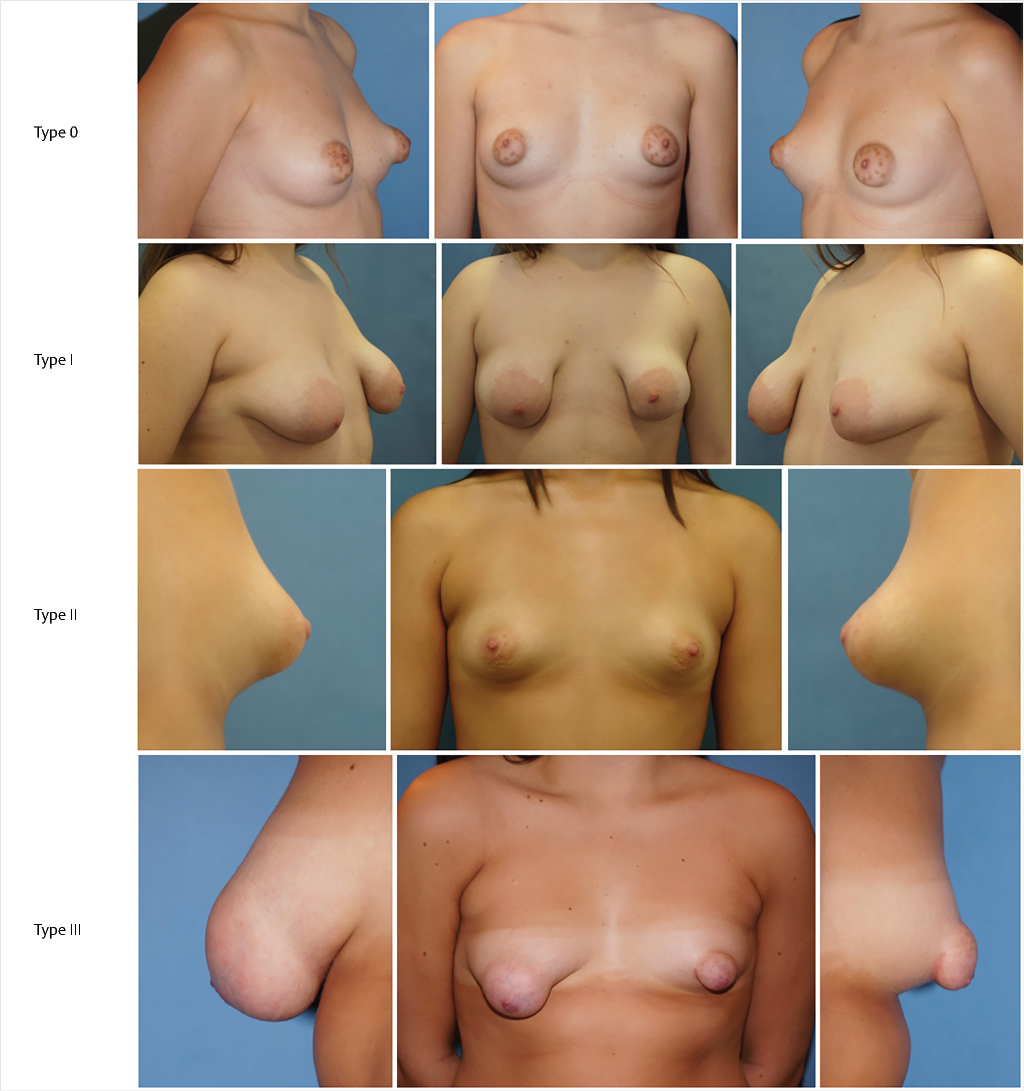

Rees and Aston found two types of the deformity but it was not until 1996 that Von Heimburg et al proposed the first formal classification, later revised by the first author in 2000. 8 , 17 , 18 Grolleau et al in 1999, Meara et al in 2000, Costagliola et al in 2013, and Kolker and Collins, in 2015, further refined Von Heimburg’s work. 12 , 13 , 19 , 20 At present, the BIBC (tuberous breast) might be classified in four types, shown in Fig. 37‑2.

Type 0: Isolated NAC herniation without further significant anomaly of the breast shape.

Type I: Deficient lower medial quadrant characteristically shaped like an italic S. The lateral breast is oversized in comparison. Overall, the breast is frequently ptotic with a normal or enlarged size. The IMF is ascended medially.

Type II: With normal or enlarged upper quadrants, lower inferior quadrants are deficient horizontally and vertically. As a result, the IMF is ascended and the areola points downward. Overall, the breast size is usually small and ptotic.

Type III: All four quadrants are deficient, resulting in a greatly restricted breast footprint and a resulting small breast. Constriction is both horizontal and vertical, giving the breast the shape of a tubercle.

Patients with severe BIBC or asymmetries have a major aesthetic concern and a related psychological impact that can be variable. On the other side, patients with minor degrees of the deformity however might not even be aware of the anomaly. Patients’ expectations are always key in postoperative satisfaction and, consequently, the importance of preoperative counseling cannot be overemphasized. Different classifications have been proposed according to the severity of presentation but clinical practice shows that many patients do not fit a particular type of deformity. Because there is not one single clinical presentation, there is not one single surgical technique. In these patients, standard mammoplasty techniques (reduction, lift, augmentation) have proved to be ineffective. Rather they should be modified according to the patients’ particular anatomy and added to the correction of the underlying tuberous findings. More than any other aesthetic procedure of the breast, breast asymmetries and tuberous deformities require a skillful surgeon than can customize the operation to the individual patient.

The usual case is a young woman with a breast asymmetry that shows a more or less tuberous anomaly in one or both breasts. Clinical examination should not focus on staging the anomaly because it does not necessarily have a prognostic or therapeutic implication. Rather, the following factors should be individually evaluated:

Areola:

Is the areola enlarged?

Is the areola protruding?

Should it be elevated?

Inframammary fold:

Is the inframammary fold elevated?

How much should it be lowered?

Gland distribution:

Which quadrants of the breast are constricted?

To what extent?

Does it need correction?

Breast volume:

Should the breast be reduced or lifted?

Does the subareolar breast require augmentation?

37.3.1 Preoperative Workup

Preoperative evaluation does not differ from other elective breast procedures. Because this group of patients is generally young and healthy (ASA I), preoperative and preanesthetic workout is quite expeditious. Bleeding diathesis not previously detected should always be ruled out in the medical record. In most patients, only usual preoperative blood tests (including coagulation) are all that is required. Six standard photographs should be taken pre and postoperatively and attached to the medical record (frontal with arms up and down, both oblique and both lateral views). Written informed consent should be taken before operation.

37.4 Treatment

37.4.1 Rationale a Surgical Strategy

Incision

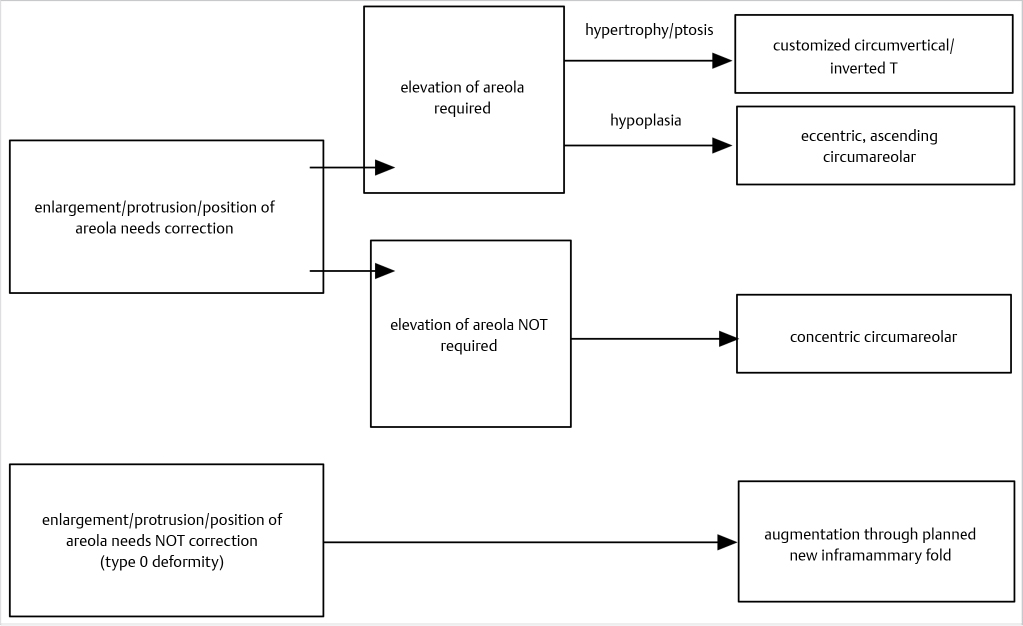

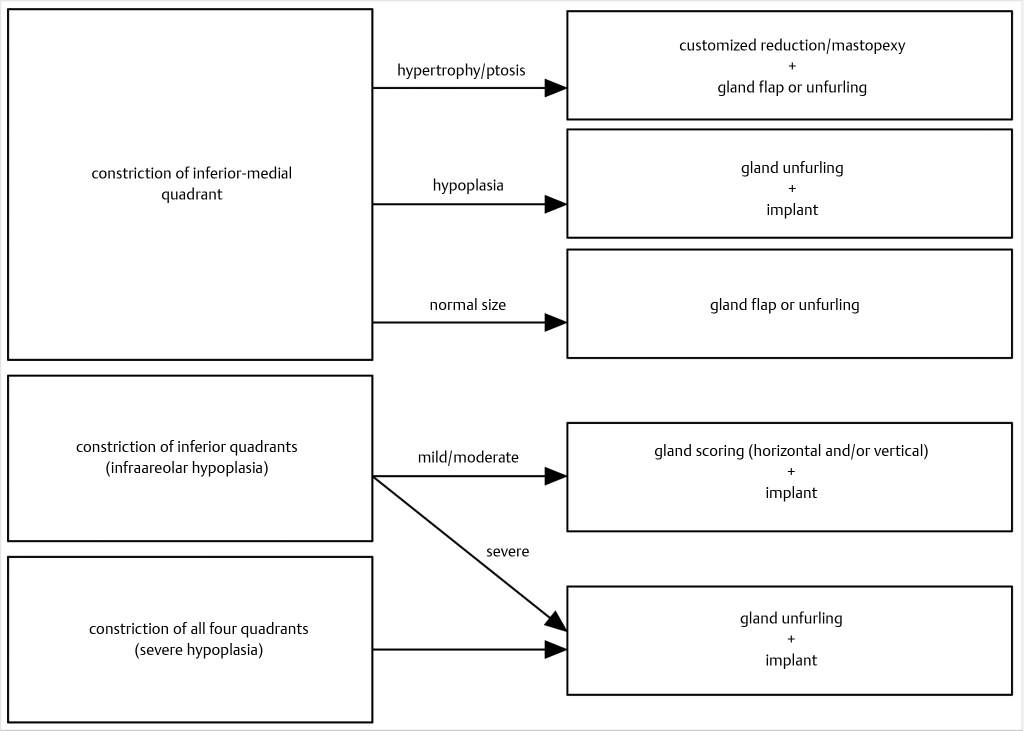

Depending on the specific findings, the incisional approach can be circumareolar, customized circumvertical/inverted T, or inframammary at the new fold. Decision-making as regards to incisions is shown in Fig. 37‑3.

37.4.2 Correction of the Inframammary Fold

Elevation of the inframammary fold (IMF) largely correlates with the underdevelopment of the inferior breast quadrants. Consequently, it will be more ascended in severe type IV cases where the lower breast quadrants are more deficient. How much should the fold be lowered is dependent on two factors, that is, the aesthetic proportions of the breast and the position of the contralateral fold. A balanced decision is thus required.

37.4.3 Correction of the Gland Maldistribution

Gland redistribution is the single most important aspect of a successful treatment in severe cases because it is the improvement of the breast shape, and not size, that really defines a good result. Surgical objectives are three: (1) release of the fascial constriction band, (2) tissue redistribution from excessive to deficient areas, and (3) attain a harmonious, aesthetically pleasant relationship among the four breast quadrants. Different options are available in Fig. 37‑4:

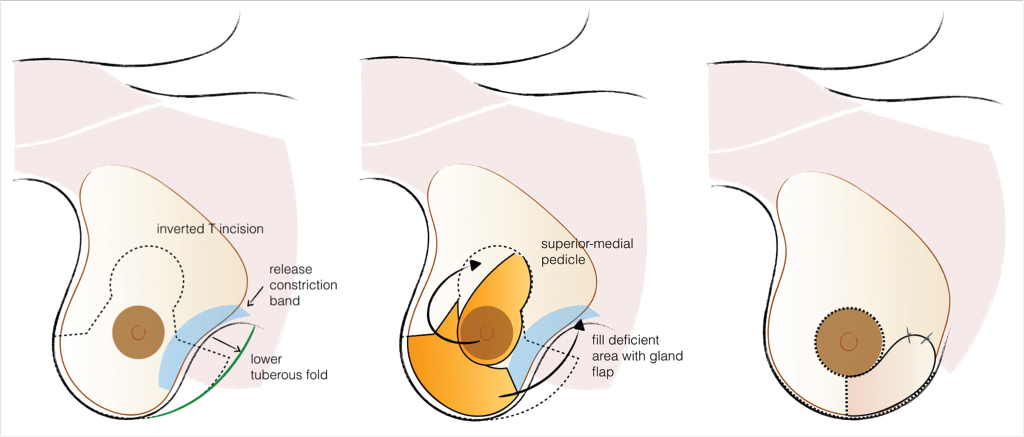

Customized Dermoglandular Flap

Characteristically indicated in type I deformities, where breast tissue is not usually deficient, the customization of the reduction/mastopexy pattern allows the creation of dermoglandular flaps that can move tissue from excessive to deficient areas, usually from inferior-lateral to inferior-medial (Fig. 37‑5).

Glandular Scoring Incisions

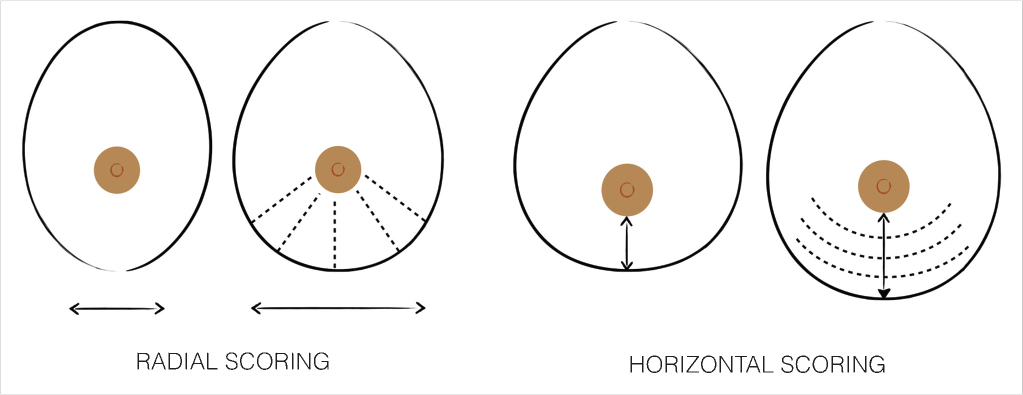

Single or multiple scoring incisions of the gland, through an anterior or posterior approach, release the fascial thickening, expand the gland and increase the compliance of the lower pole. 6 , 10 , 11 , 17 , 19 , 21 Typically, the technique is indicated in mild to moderate constriction of the inferior quadrants (mild to moderate type III cases) with the addition of implant augmentation. Expansion occurs depending on how the scoring is done (Fig. 37‑6):

Radial scoring allows a horizontal expansion of the constricted tissue and, consequently, increases the width and compliance of the inferior breast quadrants.

Horizontal scoring produces a vertical expansion of the infra-areolar breast and, consequently, increases the vertical height and compliance of the lower breast quadrants.

Scoring releases lower pole constriction but has two major limitations in severe cases: (1) it does not significantly improve the areolar protrusion because no retroareolar tissue is (re)moved and (2) it can leave irregularities of the lower pole. Going anterior or posterior will largely depend on the incisional approach (i.e., posterior scoring with the inframammary approach and anterior incisions with the circumareolar approach). Aggressive scoring might endanger vascular supply and end up with irregularities and patchy subcutaneous necrosis that can be palpated under the skin.

Gland Unfurling

First proposed by Puckett and Concannon, gland unfurling is the best technique, if not the only, to correct areolar herniation. It is also very effective in gland redistribution because it moves tissue from excessive to deficient areas. 22 , 23 , 24 Consequently, it is the procedure of choice whenever areolar herniation and gland constriction/maldistribution are significant, that is, in moderate to severe hypotrophic tuberous breasts (severe type III and type IV cases). The procedure has distinct benefits: (1) correction of the areolar herniation, (2) minimization of the risk of postoperative double bubble deformity in the usual case of implant augmentation, and (3) enhancement of the soft tissue support of the lower breast.

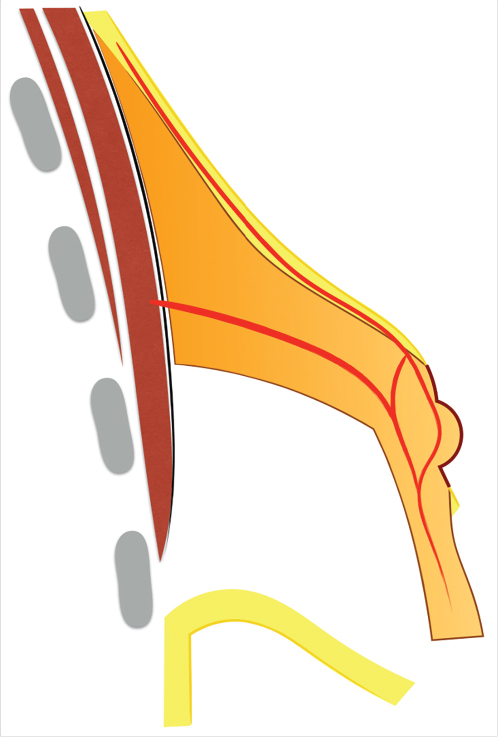

The vascular supply of the unfurled flap comes from the nipple-areola complex (NAC) vascular network (Fig. 37‑7). The NAC has a rich superficial (subcutaneous) and deep vascular supply (via transpectoral perforators) arising from the internal mammary artery, the highest (superior) thoracic artery, the anterior and posterior branches of the intercostal arteries, the thoracoacromial artery, the superficial thoracic artery, and the lateral thoracic artery. 25 , 26 Although no studies have been done regarding the vascular supply of the unfurled flap, clinical experience and basic knowledge on microvascular flap hemodynamics indicate that the vascularity of the flap is safe if properly executed: (1) the thickness at the flap base should not be less than 1 cm, (2) the retroglandular dissection should not go beyond the upper areolar margin to preserve any perforating vessels that might reach the NAC through the upper gland, and (3) the width-to-length ratio should be maintained within reasonable limits.

Areolar herniation is a major concern for many patients and relying on the areolar suture technique or tissue removal is not usually stable in the long term. 27 , 28 The unfurling technique offers long-lasting results because it moves tissue from where it is excessive (retroareolar) to where it is deficient (inferior quadrants).

37.4.4 Gland Unfurling: Surgical Technique

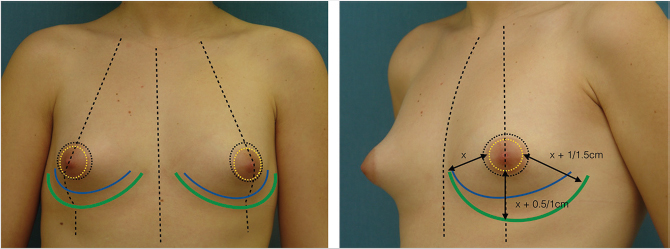

Preoperative Markings

The patient is marked preoperatively in the upright position. A vertical line is first drawn at the body midline followed by a midaxial line on both breasts. The existing fold is marked on both breasts, with a special attention to the usual fold asymmetries (which should be corrected). The planned new fold is then marked as previously published by the authors, albeit more conservatively to minimize the risk of necrosis of the infra-areolar skin. 29 , 30 A doughnut-shaped circumareolar marking is done for a final 4-cm areolar diameter. Supra-areolar skin can be deepithelialized if an areolar lift is required. Skin de-epithelialization should always be cautious when augmentation is planned (Fig. 37‑8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree