30 Genital Anomalies

Summary

Congenital anomalies of the genitalia include the following: micropenis, aphallia, ambiguous genialia, hypospadias, epispadius, cloacal exstrophy, transverse/longitudinal vaginal septum, and vaginal agenesis. Patients typically require multidisciplinary care, often with a urologist. Treatment is based on the type and severity of the deformity.

30.1 Introduction

Genital anomalies can result in debilitating functional and psychosocial sequelae if not treated properly. Beyond the obvious impact on urinary and sexual functioning, a genital defect can damage a child’s developing sense of identity and self-esteem, with significant effects on global well-being and interpersonal relationships. As such, reconstructive surgery can have a profoundly positive impact when integrated into a holistic team approach that addresses the urologic, sexual, and psychological pathologies associated with genital defects.

Genital anomalies affecting the penis are more common and more challenging to reconstruct than those affecting the vagina, and will therefore be the focus of this chapter. Penile defects requiring surgical correction in the pediatric population most often result from congenital anomalies, the most common of which are micropenis, aphallia, ambiguous genitalia, epispadias, and bladder and cloacal exstrophy (Table 30‑1). Each of these anomalies is associated with a unique set of pelvic and urologic deformities and physiologic derangements that must be addressed. Understanding how each of these malformations affects normal anatomy and sexual and urologic function facilitates optimal surgical decision-making and maximizes the likelihood of positive outcomes.

30.2 Diagnosis

Diagnosis of congenital penile anomalies typically relies on physical examination. However, deformities are often noted on ultrasound in utero; early recognition allows for prenatal counseling and can help prepare parents for what is to come. Genetic testing is often performed to confirm genetic sex and assess for underlying genetic disorders.

Aphallia is a rare condition in which the penis fails to develop in utero, resulting in complete absence of the penis. Many of these patients have associated genitourinary anomalies that must also be addressed.

The term micropenis, or microphallus, refers to a normally proportioned penis that is shortened in length (Fig. 30‑1). This condition typically results from insufficient androgen stimulation in utero. In hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, diminished androgen produced is due to insufficient GnRH stimulus from the hypothalamus. In contrast, hypergonadotropic hypogonadism describes a situation in which there is inadequate androgen release despite normal GnRH stimulus. To diagnose micropenis, the penile length must be more than 2.5 standard deviations below the age-adjusted mean.

The term ambiguous genitalia describes a broad set of congenital defects in which the external genitalia have both male and female characteristics. Micropenis is often grouped into this category. Ambiguous genitalia can occur in genetic males or females, and genetic testing is therefore important. In genetic males, ambiguous genitalia can exhibit an array of features, including a small penis resembling a clitoris, a urethral opening above or below the penis, an undifferentiated scrotum resembling labia, and undescended testes (Fig. 30‑2).

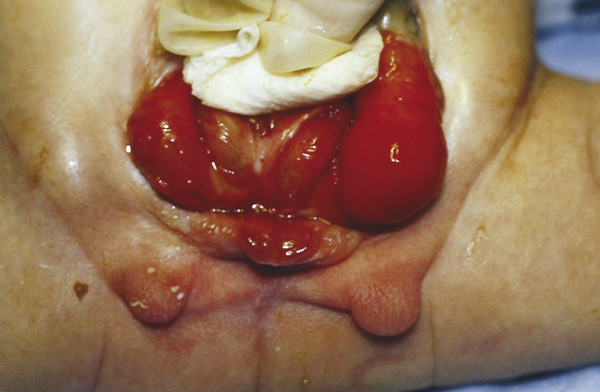

Epispadias, bladder exstrophy, and cloacal exstrophy are thought to belong to a spectrum of genital malformations termed the exstrophy–epispadias complex (EEC). EEC results from failure of mesodermal migration into the cloacal membrane that separates the ectoderm and endoderm of the anterior abdominal wall. This presumably results in premature rupture of the cloacal membrane. The timing and location of rupture dictate whether the patient will develop epispadias, bladder exstrophy, or cloacal exstrophy. Bladder exstrophy presents with a lower abdominal wall defect and severe pubic symphysis diastasis, as well as an exposed, open bladder and urethra and dorsal urethral opening (Fig. 30‑3). Cloacal exstrophy is more severe, with a bilobed bladder separated by the cecum (Fig. 30‑4). Epispadias is the mildest form of EEC and presents with a closed bladder, dorsally open urethral meatus, and mild pubic diastasis

30.3 Nonoperative Management

Congenital penile deficiency resulting from fetal testosterone deficiency may respond to testosterone treatment, delivered systemically and/or locally. Response to testosterone treatment can be seen in infancy, as well as later in childhood and adolescence. As such, when congenital hypogonadic micropenis is suspected, testosterone treatment should be considered first-line. If medical treatment fails, penile lengthening or phalloplasty can be considered.

Other than for congenital micropenis resulting from fetal testosterone deficiency, medical treatment for congenital penile defects are lacking and surgical intervention is typically warranted.

30.4 Operative Management

30.4.1 General Considerations

The preoperative assessment of a patient with a congenital penile defect begins with careful physical examination and discussion with the referring urologist to determine the extent of the defect. During this initial evaluation, it is important to consider the extent of surgery necessary to achieve an acceptable result. Less severe genital defects can sometimes be addressed by primary repair, local tissue rearrangement, and/or lengthening procedures. Situations arise in which a defect is otherwise amenable to local flap reconstruction, but the surrounding tissues have been scarred by multiple previous operations. In such cases, tissue expansion has shown great utility. Tissue expansion can also be useful in conjunction with lengthening procedures and repair of hypospadias (Fig. 30‑5). However, when a satisfactory result cannot be achieved with less complex procedures, phalloplasty to reconstruct the entire penis with pedicled locoregional flaps or free tissue transfer can be considered.

The genital defects associated with EEC can pose a difficult reconstructive challenge. Management often involves staged reconstruction of the bladder, urethra, abdominal wall, and genitalia, and requires close coordination and cooperation between the reconstructive surgeon and urologist. The genital defects associated with EEC vary in severity. In isolated epispadias, the urethral meatus is located on the dorsal surface of the penis at the penopubic angle and the glans is open dorsally. The phallus is typically shortened with dorsal chordee. Epispadias can sometimes be managed with standard lengthening procedures; however, phalloplasty can be used to achieve favorable results in severe cases. In cases of exstrophy, the penis can be halved and separated from the midline. In such cases of severe deformity, phalloplasty is indicated.

In the past, aphallia and severe congenital penile defects were treated with gender reassignment, with bilateral orchiectomy, penectomy (when a penis was present), labioplasty, clitoroplasty, and vaginoplasty. The realization that these patients typically maintain a male identity following surgery, as well as the emergence of effective techniques for phalloplastic reconstruction, has resulted in this practice falling out of favor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree