3 The Use of Costal Cartilage for Dorsal Augmentation and Tip Grafting

Pearls

Rhinoplasty in an East Asian patient requires attention to a different set of aesthetic goals than for a Caucasian patient. Digital image morphing software is very important to be able to communicate proposed changes to the patient population.

The East Asian nose is deficient in structural support. Augmentation is necessary to achieve the desired refinement. A structural approach to East Asian rhinoplasty allows the surgeon to accomplish the established goals.

Although alloplastic implants have been widely used in East Asian rhinoplasty, autologous costal cartilage is being used more frequently in the East Asian nose as a desirable alternative.

A thorough history, including previous surgery, infection, implants, or injectable fillers, is necessary to elucidate factors that will increase the complexity of the surgery.

For safe and successful costal cartilage harvest, the surgeon must be familiar with the anatomy of the rib cage to select the rib with the best contour for the necessary grafts.

The barrier to mastering costal cartilage grafting is learning to judge where to use each potential graft and how to properly prepare the grafts.

Age is the most important factor to consider when carving costal cartilage.

One of the most important concepts in successful costal cartilage grafting is to carve the material sequentially with repeated cycles of carving, soaking, and drying the graft to identify its natural bend.

Although cross-hatching and splinting are useful, it is important to understand that these techniques cannot overcome the selection of an inappropriate piece of costal cartilage.

In the setting of East Asian dorsal augmentation, osteotomies are usually unnecessary.

Serial carving, perichondrium camouflage, and rigid fixation are key strategies in performing dorsal augmentation.

Tip augmentation, accomplished with shield or horizontal onlay grafts, creates projection and refinement; however, a stable foundation is required to control length and rotation.

In the East Asian nose, with its wide airway and thicker lateral sidewalls, alar batten and alar rim grafts are infrequently indicated.

After structured rhinoplasty with autologous costal cartilage augmentation, technically difficult base reductions may be required to balance the nose.

Introduction

Aesthetic rhinoplasty of the East Asian face requires a different approach than that used for the Caucasian face. This alternative approach is due to differences in nasal anatomy, patient expectations, and surgical techniques. Regardless of the approach, the principles of structure rhinoplasty remain the same: surgical manipulation of the nasal construct causes weaknesses susceptible to scar contracture. For a longterm aesthetic and functional outcome, augmentation must withstand the distorting forces of tissue healing.1 Supporting the nose by augmentation requires a significant amount of grafting material. Autologous costal cartilage provides a bountiful source of material that can be used to produce a lasting aesthetic and functional result in the East Asian face.

Patient Evaluation

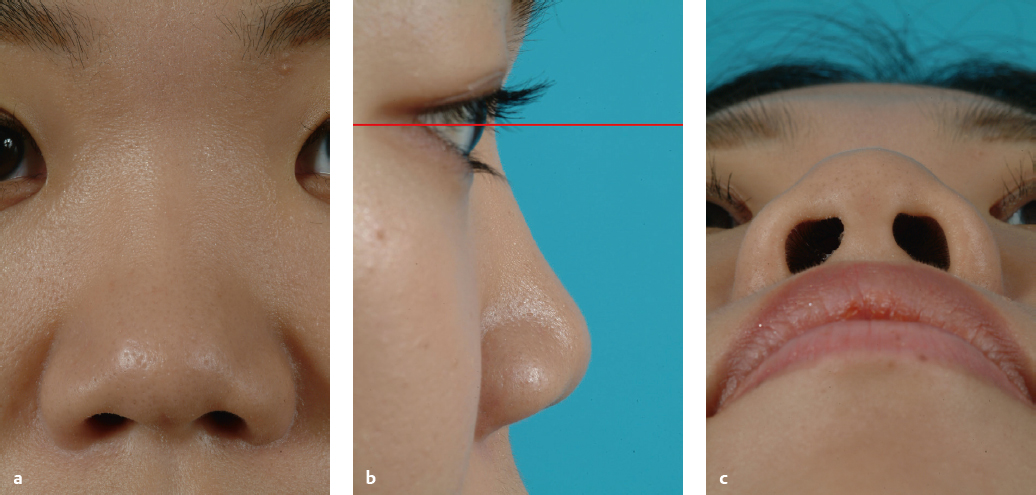

The initial patient consultation starts with a complete history and physical examination to diagnose the structural problems that cause the undesirable aesthetic features of the patient’s nose. In addition, the consultation should elucidate any history of nasal obstruction or complicating history: previous surgery, infection, or foreign bodies, including implants and injectable fillers. The physical exam will confirm characteristic anatomic features of the East Asian nose, including: flat glabella; low nasal dorsum with caudally placed nasal starting point; thick, sebaceous skin overlying the nasal tip and supratip; weak lower lateral cartilages; small cartilaginous septum; foreshortened nose; retracted columella; and thickened, hanging alar lobules (Fig. 3.1).2

Preoperative Evaluation

The preoperative evaluation continues with the photodocumentation of these anatomic features in standardized views (frontal, lateral, three-quarter, and base views). Three-dimensional stereophotogrammetry can be performed at this point to provide a baseline for postoperative comparison and measurements.3

Digital image morphing software provides an opportunity for a frank discussion between the patient and surgeon. Photographic manipulation is a transparent medium for the communication of expectations, prioritization of goals, and identification of potential pitfalls. Typical goals for the East Asian nose include elevation of the nasal dorsum, refinement of the nasal tip, narrowing of the nasal base, and correction of columellar retraction. Furthermore, the software can prompt subjective preferences (Westernized versus natural) and objective parameters: nasal length, dorsal height, projection, rotation, width, and tip refinement. Throughout this exchange, the surgeon needs to counsel the patient that the frontal view is the first priority. Improvements will be made regarding the profile and base views; however, the frontal view will not be sacrificed for such improvements. Agreement on the planned outcome is necessary prior to the operative date.

Preoperative Discussion and Counseling

Further preoperative counseling should include incision placement (columellar and alar for base reduction), increased stiffness of the nose, extra operative time for costal cartilage harvest, complications (pneumothorax and warping), and postoperative course (swelling, followup schedule). This is the time to tell the patient that to achieve the goals of dorsal augmentation and tip refinement in the setting of thick skin, a large amount of grafting material will be used, essentially making the nose bigger. This is necessary in East Asian rhinoplasty, as the primary cases will often be lacking in septal cartilage. Similar to the quality of the upper and lower lateral cartilages, the septum is thin and weak. According to the principles of structure rhinoplasty, destabilizing the already weak cartilage by reducing the structural components will allow scar contracture to have an even more dramatic and often undesirable effect. This emphasizes the need for augmentation. To address the lack of material, it is the authors’ opinion that autologous costal cartilage can provide the best aesthetic and functional results in the East Asian patient’s nose. Costal cartilage is inherently stronger and, therefore, can be carved thinner, avoiding bulk in the nose. The vascular demand is less than for auricular cartilage, decreasing rates of resorption. Costal cartilage is available in greater volume, providing all of the necessary grafts from a single donor site. As there is less cautery required for hemostasis at the rib compared with the ear, donor site pain is also less.4 Postoperative complications seen with synthetic implants—wound infection, graft extrusion, injured skin envelope—are rare; however, the risk of complications remains for a lifetime (Fig. 3.2). For these reasons, autologous costal cartilage is ideal for the East Asian nose and is the focus of this chapter.

Surgical Techniques

The senior author (DMT) performs augmentation rhinoplasty through a standard external rhinoplasty approach under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation in an outpatient surgicenter. The surgeon injects the chest and nose with 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine prior to prepping and draping to allow for optimal vasoconstriction. While injecting the septum, the surgeon can initiate the elevation of mucoperichondrial flaps via hydrostatic dissection. At the same time, needle palpation can differentiate cartilaginous versus bony nasal septum, for an estimation of available material for grafting. The nose is packed with cotton pledgets soaked in 0.05% oxymetazoline, for further vasoconstriction.

Opening the Nose

By opening the nose first, the surgeon can make a clear assessment of the amount of cartilage grafting material required to complete the case. A midcolumellar inverted-V incision is demarcated with anticipation of the tip projection outcomes. If there is a planned increase of projection, the incision is drawn slightly (1 mm) posterior to the midcolumella. The columellar incision is made with a no. 11 blade scalpel. Marginal incisions and columellar incision extensions are made bilaterally with a no. 15 blade scalpel. Using Converse scissors, the incisions are connected sharply. Particular attention is directed to preserving the soft tissue triangles as well as maintaining an adequate cuff of tissue separating the marginal incision from the alar rim, ~ 3 mm. Carelessness here can result in notching of the alar margin. Using three-point retraction, the skin envelope is raised sharply. Preserving the subdermal plexus by minimizing blunt spreading improves hemostasis and minimizes postoperative edema. Sharp dissection continues from the lower lateral cartilages superiorly to the cartilaginous dorsum and bonycartilaginous junction. A key point is to use the Joseph periosteal elevator in a limited fashion, preserving a tight pocket in anticipation of a dorsal graft. A tight pocket will restrict graft movement and aid in rapid fixation to prevent warping.5 Additionally, as most Asian patients do not require a hump reduction, wide subperiosteal dissection is not warranted.

The nasal septum is exposed by lateral retraction of the lower lateral cartilages and sharp dissection to the anterior septal angle. Bilateral mucoperichondrial flaps are raised in the appropriate subperichondrial plane to decrease the risk of septal perforation. Again, as most Asian patients do not require a hump reduction, a submucous resection may be performed at this time, while preserving 15-mm caudal and dorsal struts. The septal cartilage harvest will provide a small volume of grafting stock that is not particularly strong but is at low risk for warping.

After deconstructing the nasal framework, the surgeon surveys the nose and reviews the grafts anticipated to be necessary to resupport the nose, augment the dorsum, and refine the nasal tip before changing gloves and turning to the chest.

Costal Cartilage Harvest

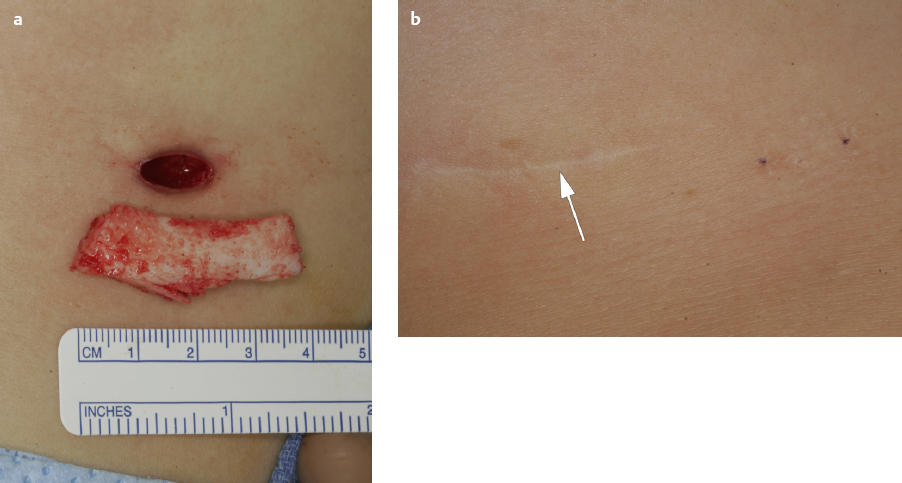

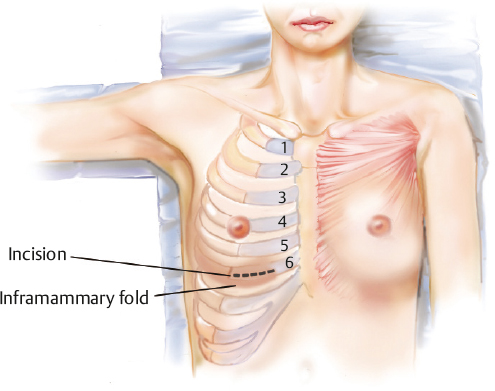

Prior to the costal cartilage harvest, the surgeon must consider several patient factors, including age, breast anatomy, and excessive scarring. Despite variability in nasal anatomy, costal cartilage anatomy is relatively consistent across different ethnic backgrounds. The most important factor is the age of the patient.6,7,8 Younger patients are at higher risk for graft warping. Older patients are at higher risk for fracturing during harvest or graft manipulation. Patients between the ages of 30 and 50 are generally at lower risk of warping, and fracturing can usually be prevented with careful handling of the grafts. In the East Asian patient population, the average volume of breast tissue obligates the surgeon to minimize the incision length for the sake of a smaller scar that cannot be hidden in an inframammary crease (Fig. 3.3).

With the increased prevalence of breast augmentation, incisions hidden in the inframammary crease may risk puncture or trauma to the breast implant. Furthermore, ribs directly under an implant (typically rib 6) provide important structural support to the breast implant. Harvest of a supporting rib may result in undesired asymmetries of the breast position or discomfort from the weight of the implant lying on the manipulated rib. Hypertrophic scarring and keloid formation should be elucidated from the patient’s history for appropriate counseling preoperatively. Abnormal chest wall anatomy and elevated body mass index may also increase the complexity of the harvest.

When selecting a rib to harvest, one must be familiar with the relationships of the individual ribs to one another. The fifth rib has a free superior and inferior margin; however, it can lie underneath breast tissue or pectoralis muscle. It is also relatively short and curved and may not be of adequate size for dorsal augmentation. The sixth rib typically has a free superior margin, but the inferior margin is connected to the seventh rib medially. The sixth rib is usually at an ideal depth, but it has a slight genu that may not be ideal if a long straight segment is needed (Fig. 3.4).

The seventh rib is straighter and will usually have connections with the surrounding ribs on both the superior and inferior borders. The eighth and greater nonfloating ribs will have significant connections to surrounding ribs and are thinner and may not be of adequate width for a dorsal graft. The seventh and eight ribs are located slightly deeper underneath the skin compared with the sixth rib. As the ribs are followed medially, they course deeper under the subcutaneous tissue. Ultimately, the rib with the best contour for the necessary grafts should be selected, but generally the cartilage component of the seventh rib has the best contour.

After these considerations, the surgeon should manually palpate the chest wall around the potential ribs for harvest. Once oriented, careful needle palpation with a 3.75-cm (1.5-in), 27-gauge needle localizes the osseocartilaginous junction and determines the degree of ossification. Be forewarned: Blind needle pokes may puncture the pleura and lung parenchyma, resulting in a closed tension pneumothorax.

Once the ideal rib has been selected and characterized, the overlying skin is marked and the surrounding area is injected with 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. Costal cartilage from the right side is preferred to avoid injury to the pericardium and confusion of postoperative discomfort with angina. The donor site is a separate sterile field, and cross-contamination with nasal flora should be avoided by changing gloves and using a separate set of surgical instruments.

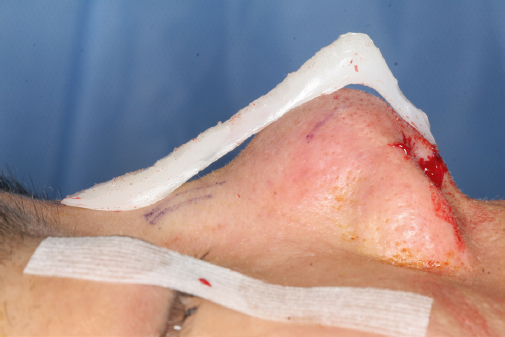

Due to the senior author’s experience, he is able to start with a 10-mm incision that may stretch to a final length of 12 or 13 mm. The chest incision is made small to minimize the visible scar and morbidity to the patient. For patient safety, surgeons should continue to use a larger incision until they are familiar with the dissection.5 After a skin incision is made, sharp dissection continues through the subcutaneous fat to the fascia overlying the muscle. For hemostasis, bipolar cautery is used to minimize postoperative pain. A no. 15c scalpel is used in the small window to sharply incise the muscle fascia. The muscle is bluntly spread to decrease bleeding and postoperative pain. The keyhole perspective is maintained with retractors to view the perichondrium overlying the rib. This window can be translated medially and laterally along the course of the rib. Recall that the rib’s course is not a straight line, but an oblique and threedimensional arc that changes depth as it curves from lateral to medial. Through the process of exposing the rib, the boundaries of the rib should be confirmed by careful needle palpation.

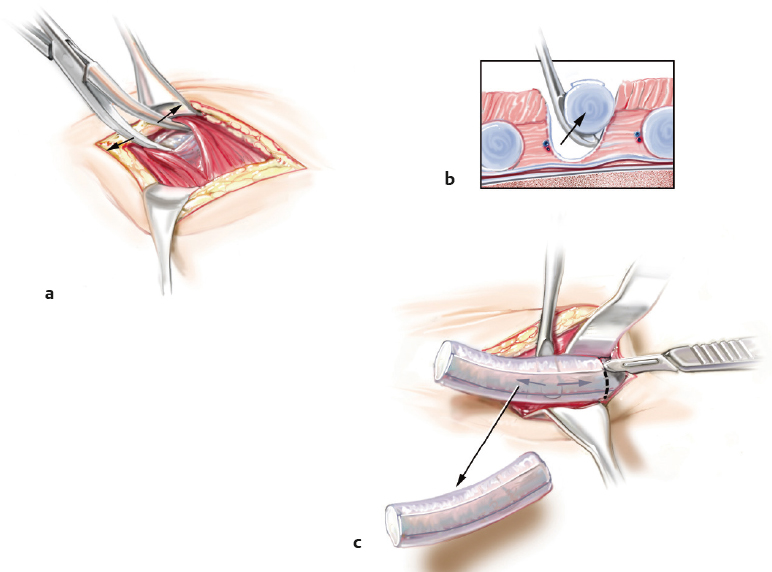

Once exposed, the anterior perichondrium is incised with a no. 15c scalpel along the lateral limit, superior border, and inferior border of the rib. The perichondrium is mobilized with a Freer elevator and harvested sharply. The rest of the perichondrium will remain intact to ensure the integrity of the harvest site.

Having opened the nose, the surgeon should have in mind the grafts that will be used to structure the nose. The harvested costal cartilage should be taken in dimensions appropriate for the planned grafts. Usually 3 to 4 cm of costal cartilage is harvested. To ensure an intact harvest site and avoid violation of the pleura, the first incision should start by using the sharp end of the Freer elevator to cut 0.5 mm from the superior and inferior margins of the rib. After 50% penetration through the depth of the cartilage, the incision is completed with the blunt end of the Freer elevator. The goal is to maintain a protective cuff of cartilage that guides the dissection into a safe plane above the posterior/deep perichondrium and pleura. Medial and lateral boundaries of the cartilage are first sharply incised with a no. 15c blade through 10% of the thickness, followed by a sharp Freer elevator through 70%; the blunt Freer elevator completes the final 30%. Once mobilized on inferior, superior, lateral, and medial borders, the undersurface of the rib is freed with a Freer elevator using a lifting motion (Fig. 3.5). Following the harvest, the medial and lateral edges of the remaining cartilage are smoothed with Takahashi forceps.

The wound bed should be inspected for violations of the perichondrium or pleura, with potential injury to the lung parenchyma and a resulting pneumothorax. The wound bed is filled with saline. A Valsalva maneuver confirms an intact harvest site, if the saline volume is constant and there are no bubbles. Any defects should be repaired immediately. To repair such defects, the lung is deflated and a catheter is placed in the defect. A pursestring stitch should be placed around the defect and tied after the catheter is placed on suction, and removed when the lung has been maximally reexpanded. A repeat inspection and Valsalva maneuver are warranted. Injury to the lung parenchyma may require a chest tube insertion.

The chest harvest site remains open for the duration of the operation as a contingency for more graft material or perichondrium. The site is protected with an antibiotic-soaked gauze sponge and blue towel. After completing the rhinoplasty, the surgeon again changes gloves. The rib harvest site is irrigated and inspected. Closure begins with 3–0 PDS suture to reapproximate the muscle and its fascia. Careful attention is paid to this layer of closure to ensure the separation of muscle and fascia from the overlying subcutaneous tissue. A suture spanning the two layers will result in tethering of the overlying tissue to the deeper fascia, inhibiting independent motion. The subcutaneous fat is reapproximated with 4–0 PDS suture. The deep dermal layer is closed with 5–0 PDS suture. The subcuticular layer is closed with 6–0 Monocryl suture. The cutaneous layer is reapproximated and everted with 5–0 fast-absorbing gut suture. Finally, cyano acrylate adhesive is applied superficially to seal the wound.

The senior author recommends routine postoperative chest X-ray and a period of observation after costal cartilage harvest until the surgeon is familiar with the procedure.

For patients with a propensity for keloids or hypertrophic scars, Kenalog (10 mg/mL) may be injected at the costal cartilage harvest site. After the skin glue falls off, silastic sheeting may be utilized to help minimize the visibility of an unsightly scar.

Costal Cartilage Carving

At this point of the procedure, the surgeon needs to focus on the critical step of cartilage carving. Regardless of the amount of energy expended on the harvest or complications encountered during the harvest, the surgeon cannot lose concentration. The barrier to mastering costal cartilage grafting is learning to judge where to use each potential graft and how to properly prepare the graft. Prior to any carving, the surgeon should repeat the survey of the nose and plan all of the necessary grafts; one should not carve the grafts as they are needed in the procedure. If a large dorsal augmentation is planned, an appropriately thick piece of costal cartilage stock needs to be preserved for the dorsal graft, starting with the first cut into the costal cartilage. Improper carving, selection, or fixation of the costal cartilage grafts could potentially create more deformity than the deficiency one is trying to repair.

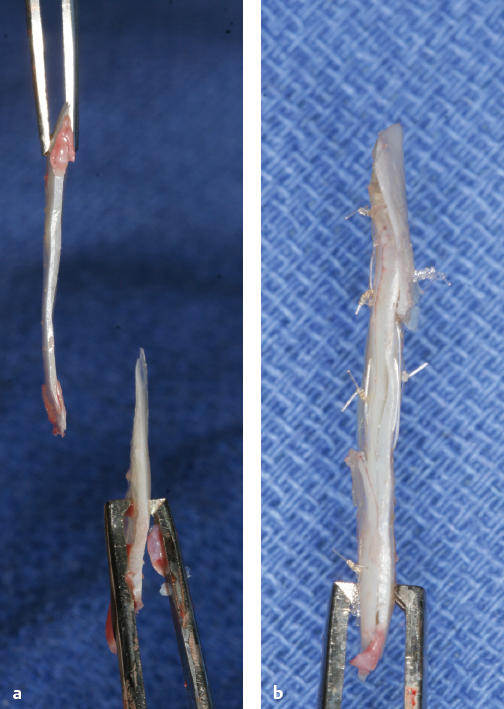

Again, age is the most important factor to consider when carving the costal cartilage. The cartilage will have a whiter-appearing outer portion, which contains a fibrous component. In the younger patient, the outer portion of the rib has an increased tendency to bend. In the older patient, the outer fibrous component is less prone to fracture, in which case it is preserved.9,10 The central piece may bend less than the peripheral slices; however, it may be brittle and prone to fracture in older patients. With the properties of the central and outer/fibrous component in mind, the surgeon may begin to carve the costal cartilage.

One of the most important concepts in successful costal cartilage grafting is to carve the material sequentially. Repeating soaking and drying cycles between carvings encourages the cartilage to reveal any tendency to bend in 30 to 60 minutes. First the harvested segment is cut into three pieces along the longest axis, creating anterior, central, and posterior slices. These pieces are allowed to soak and then they are carved into thinner pieces. After allowing the freshly carved cartilage to show its natural bend, the key is to utilize that bend when selecting individual pieces for specific grafts. Most grafts require some degree of curvature for optimal function. The inherent strength of costal cartilage allows it to be carved very thin to decrease the bulk in the nose; however, a thickness less than 1 mm increases the risk of torquing. Attempting to carve the cartilage into a straight piece is not advised, as it may result in unpredictable warping after fixation.

Limited manipulation of the costal cartilage is possible and is particularly useful if warping is a concern. The two techniques available to the surgeon are cross-hatching and splinting, which may be used separately or in combination. Cross-hatching consists of partial-thickness cuts into the concave side of a curved piece of cartilage to release the bowing forces on the graft. The degree of release is difficult to predict, and overzealous cross-hatching may result in overcorrection and curvature in the opposite direction. Partial-thickness cuts on the convex side increase the existing curvature. Splinting involves the summation of curves. Two curved pieces are sutured together with opposing concavities to create a single straight graft (Fig. 3.6). Although cross-hatching and splinting are useful, it is important to understand that these techniques cannot overcome the selection of an inappropriate piece of costal cartilage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree