25 Endoscopic Forehead and Brow Lift

Pearls

The aging upper one-third of the face is assessed as a unit, and all aesthetic units are interrelated.

The aging brow can have a dramatic impact on general facial expression, creating a tired or fatigued appearance.

Ptosis of the aging brow can simulate dermatochalasis of the upper eyelid.

The approaches to forehead and brow lift can be divided into open and endoscopic. Open approaches include trans-blepharoplasty, direct, midforehead, trichophytic, and coronal.

The principles of endoscopic forehead and brow lift (EFBL) are the making of smaller, well-camouflaged incisions; maximal release of muscular and periosteal attachments; cephalic rotation of the scalp, forehead, and brow complex; and fixation of the complex at the desired height.

When a combined approach to dealing with the brows and eyelids is planned, EFBL is done first to set the height of the eyebrows and determine the amount of skin to be excised.

The advantages of EFBL over the coronal approach are camouflaged incisions, shorter recovery time, and less risk of alopecia and scalp numbness.

The disadvantages of EFBL are that the hairline can be raised, redundant forehead skin cannot be excised, less control in asymmetrical brows, increased cost due to more sophisticated instruments being used, and learning curve.

EFBL has been shown to be effective with lasting outcomes. Different fixation methods are available.

Introduction

Forehead and brow lift is an important component of upper face rejuvenation. This often complements the results of upper blepharoplasty, and the reverse is also true. Forehead lift results in a smoother contour with resolution or improvement of forehead and glabellar rhytids, while brow lift aims to elevate the brows to an aesthetically pleasing position and also to sculpt an aesthetically pleasing shape. In the process of achieving this, incisions have to be made in the forehead and scalp or along the hairline, where they may be too conspicuous for patients to accept. Hence, the concept of the minimally invasive procedure was developed. and the endoscopic forehead and brow lift (EFBL) was popularized.

This was first described by Vasconez et al1 in 1994 in the United States, where they detailed the use of endoscopes to guide the release of the supraorbital and glabellar tissues. The dissection was in the subgaleal plane, but the fixation was not well described. Subsequently, multiple variations in dissection and fixation techniques have been reported.

In general, EFBL has been shown to produce excellent results; however, it has not been proven to be superior to the open techniques. A study in 2002 by Puig and LaFerriere2 compared the results of open approaches versus EFBL. They found no statistical difference in the measurable results between these procedures. In a systematic review of open versus endoscopic techniques published in 2011, there is no clear evidence to indicate that open methods are inferior to the endoscopic approaches.3 However, EFBL does offer some advantages over the open techniques. The incisions are smaller and well hidden within the hairline. It results in less blood loss and also reduced scalp hypoesthesia. Disadvantages include the increased cost for the more sophisticated instruments and also a learning curve to overcome. The ideal fixation method is still controversial but many different techniques seem to work well.

Relevant Anatomy

Facial proportions are divided into horizontal thirds and vertical fifths. The upper face occupies the upper third and starts from the trichion to the glabella. The temporal region is also important when dealing with the lateral brow position. Hence, knowing the anatomy of the forehead and temporal region is of paramount importance to ensure a safe and complication-free forehead and brow lift.

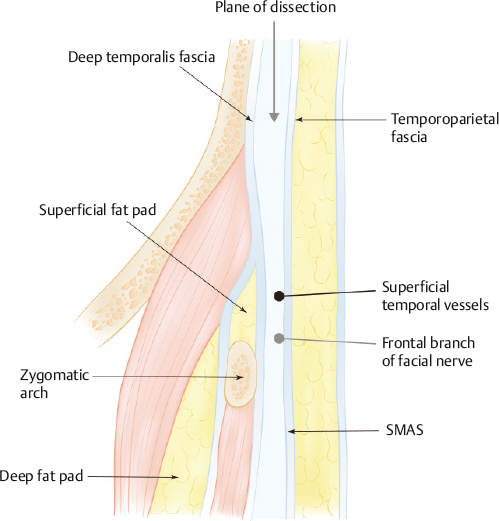

The forehead is made up of five layers. From superficial to deep, they are skin; subcutaneous fat; galea aponeurotica, which splits to envelop the frontalis muscle; loose areolar tissue; and periosteum. At the brow area is the subbrow fat pad or the retro-orbicularis fat pad, found just below the orbicularis oculi muscle but above the periosteum. As for the temporal region, the layers are skin, subcutaneous fat, temporoparietal fascia, deep temporalis fascia, and finally the temporalis muscle. The deep temporalis fascia splits into superficial and deep layers to envelop the superficial temporal fat pad ~ 2 cm above the zygomatic arch. The superficial layer attaches to the superficial superior margin of the zygomatic arch, and the deep layer attaches to the deep superior margin. Deep to the deep layer lies the deep temporal fat pad, which represents a superior extension of the buccal fat pad.

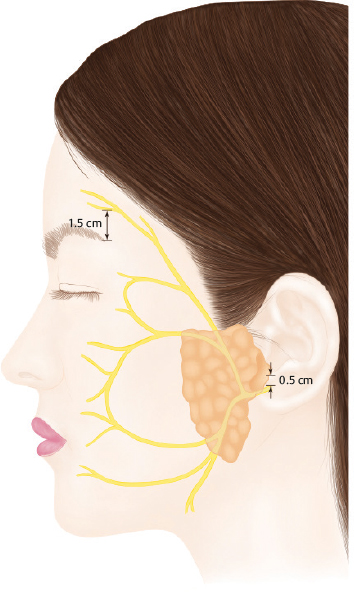

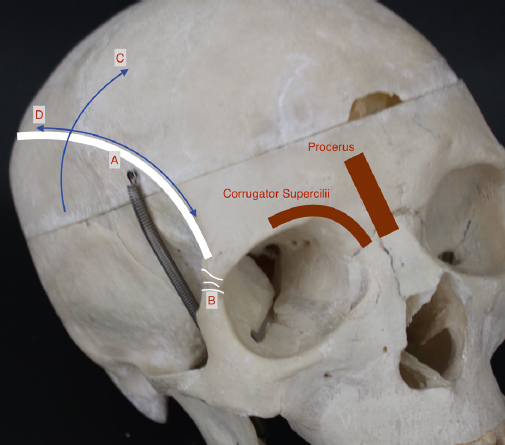

The frontal branch of the facial nerve courses within the temporoparietal fascia (Fig. 25.1) along the Pitanguy line.4 This is a line that runs from 0.5 cm below the tragus to 1.5 cm above the lateral eyebrow (Fig. 25.2).

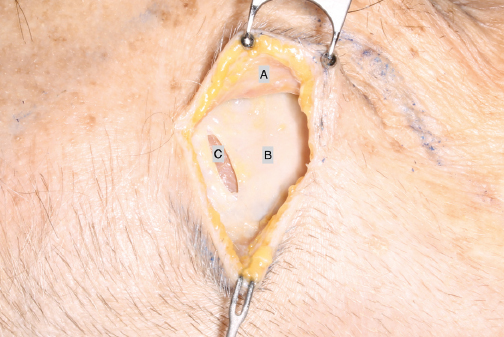

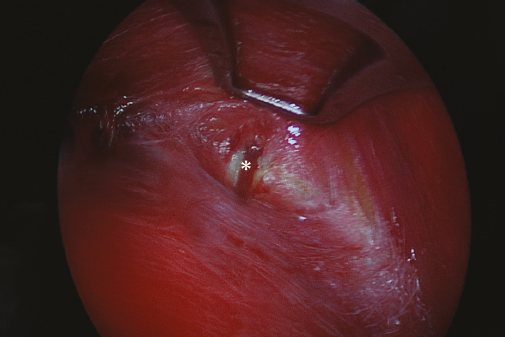

A loose areolar plane separates the temporoparietal fascia from the deep temporalis fascia. This is a relatively avascular plane, and it is deep to the frontal branch of the facial nerve, and hence is an ideal plane of dissection during EFBL (Fig. 25.3). However, the medial zygomatico-temporal vein or the sentinel vein can be found traversing this plane (Fig. 25.4). The vein can be found ~ 1 cm lateral to the frontozygomatic suture line, and the frontal branch is usually found just cephalad to it. Trinei et al5 mapped out a zone of caution based on the location of this vein and its proximity to the frontal branch, and found that the nerve was always within a 10-mm radius of this vessel. A more recent study by Sabini et al found this radius to be much closer, within 0 to 2 mm.6 Extreme care should be taken in this area since a disruption of the vein can lead to bleeding, impaired visualization, electrocautery, and then injury to the facial nerve.

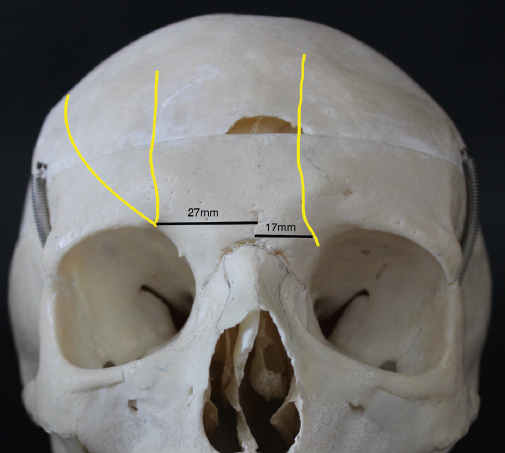

The supraorbital notch or foramen transmits the supraorbital nerve, a branch of the ophthalmic nerve. This can be located ~ 27 mm lateral to the glabellar midline, or typically within 1 mm of a line drawn in a sagittal plane tangential to the medial limbus (Fig. 25.5). As it emerges from the foramen or notch, it divides into a deep and a superficial branch. The deep branch runs superolaterally, parallel and ~ 0.5 to 1.5 cm medial to the superior temporal line in the loose areolar tissue between the galea and periosteum. The superficial branch usually divides into multiple branches, piercing the frontalis muscle and running superficial to it. The deep lateral branch supplies sensation to the lateral posterior forehead and scalp while the superficial medial branch supplies sensation to the forehead along the midline and frontal scalp.

The supratrochlear nerve, also a branch of the ophthalmic nerve, can be found ~ 17 mm lateral to the glabellar midline or at an average of 9 mm medial to the exit of the supraorbital nerve through a notch (Fig. 25.5). The nerve penetrates the corrugator and frontalis muscles as it courses superiorly along a line tangential to the medial end of the brow. It supplies sensation to a central vertical strip of forehead and the medial upper eyelid. The infratrochlear nerve exits just below the supratrochlear nerve around the medial orbital rim, and it provides sensation to the upper nose and medial orbit.

It is important to know that there is fibrous ligamentous thickening around the orbital rim and temporal area that fixates the brow and forehead complex. These firm attachments need to be released for the brow and forehead to be adequately and effectively lifted. The arcus marginalis is an area of localized thickening of the aponeurosis at the superior orbital rim where the orbital septum attaches to the orbital bone. Another area of this thickening is the conjoint tendon or the zone of fixation at the temporal fusion line (Fig. 25.6). This is an area of fusion between the galea, temporoparietal fascia, and deep temporalis fascia and the periosteum of the frontal bone. It also marks the transition between forehead and temple. Finally, there is the orbital retaining ligament centered over the frontozygomatic suture that holds the lateral part of the brow down.

The musculature also plays an important role in the position and shape of the brow. This is divided into the brow elevators and depressors. The elevators are the frontalis muscle and are supplied by the frontal branch of the facial nerve. The depressors are the procerus, corrugator supercilii, and the orbicularis oculi muscles, supplied by the frontal and zygomatic branches of the facial nerve. The depressors of the brow need to be adequately dealt with to achieve an effective lift. They are usually in a balanced state maintaining the position of the brow. Any over- or under-activity of either will cause the brows to be raised or lowered.

Considerations

Brow Aesthetics

Before assessing the patient, the surgeon needs to know what the ideal brow position and shape are, and also to understand the problem that is being addressed. The ideal brow position and shape vary with sex, age, race, culture, and fashion trends. Hence, it is important to understand the patient’s needs and concerns before embarking on surgery. There is no one standard surgery for all patients.

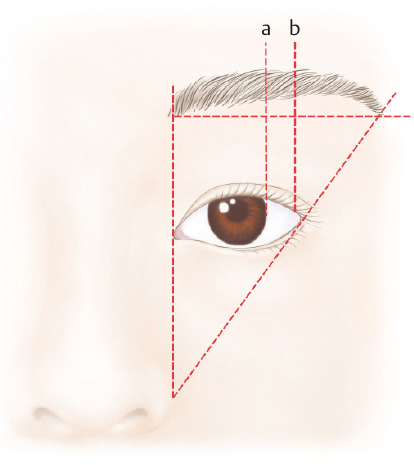

The brow can be analyzed in terms of its shape, position, mobility, and symmetry with the contralateral side. The medial brow should begin at a vertical line drawn from the alar facial crease to the medial canthus, and at ~ 1 cm above the medial canthus (Fig. 25.7). It should progress laterally in a club-like configuration, gradually tapering toward its lateral end. It should ascend superiorly to the apex and then turn inferiorly. The lateral brow should end at an oblique line from the alar facial crease to the base of the lateral canthus. The highest point, or apex, of the brow should be at the lateral limbus. However, some believe that this high point should be more lateral than the lateral limbus and closer to the lateral canthus. Finally, the medial and lateral ends should lie at about the same horizontal plane. The shape of the brow can be described as flat, arching, downward slanting, or upward slanting. Most important, the brows on the two sides should be in symmetry.

For males, the brows should be positioned at or near the supraorbital rim with minimal arching and be more horizontal. Creating the arch in a man will be unattractive. For females, the brows should be positioned slightly superior to the supraorbital rim with a subtle arch as described previously.

Aging Process

As we age, the brow undergoes descent due to gravitational forces and loss of skin elasticity. The medial brow height is maintained by the balance between brow elevator (frontalis) and depressors (corrugator supercilii and procerus). However, as the frontalis stops at the temporal fusion line, the lateral brow receives unopposed depression from the lateral part of the orbicularis oculi due to lack of frontalis action. Hence, the lateral brow descends earlier and more severely than the medial brow.

As the lateral brow descends, it creates hooding of the lateral part of the eyelid, which may cause obstruction of the visual field. Ptotic brows can portray the appearance of anger, sadness, worry, and weariness despite the absence of emotional intent or causative physical condition.

Forehead and glabellar rhytids develop as a result of repeated muscular contraction during facial expression and also the process of aging, which produces skin thinning and loss in elasticity.

Relationship with the Eyelid

Analysis of the brow would not be complete without the analysis of the eyelid, as they both contribute to the upper face aesthetics and undergo a similar aging process. Very often, brow ptosis and dermatochalasis contribute to lateral hooding. Hence, performing a brow lift or blepharoplasty alone may not adequately deal with the problem. Combining a brow lift with a blepharoplasty allows a more conservative resection of the upper eyelid skin and is a common procedure.

When assessing a patient for a blepharoplasty, it is imperative to assess the brow position as well. If the brows are ptotic to begin with, performing a blepharoplasty may exacerbate this and create an unnatural appearance. In this scenario, it is best to first raise and stabilize the brows before an upper blepharoplasty.

Another situation is when a patient presents with an asymmetric brow position secondary to over-activity of the frontalis on one side. This can occur from unilateral upper eyelid ptosis where the patient habitually raises one brow in an attempt to improve the visual field. Hence, the brows need to be assessed with the frontalis at rest to avoid intervention in what is a physiologic condition rather than an anatomic one. The correct management in this situation would be to correct the ptosis rather than the brow position. With over-activity of the frontalis due to brow ptosis, eyelid ptosis, or dermatochalasis, dynamic forehead rhytids will gradually become static, requiring a forehead lift.

Indications

The three main indications to lift the forehead and brow are forehead and glabellar rhytidosis, brow ptosis, and brow asymmetry.

Forehead and glabellar rhytidosis can be occasionally treated with botulinum toxin injection into the depressor muscles, a chemical brow lift. Botulinum toxin may have a stronger indication in a prophylactic role. Deeper rhytids can be addressed with soft tissue fillers, occasionally in combination with botulinum toxin. However, these methods are temporary and require repeated treatments to maintain the desired outcome.

In a surgical forehead lift, the wrinkles are mechanically pulled upward and flattened. The muscular elevator and depressors can be resected, separated, or weakened surgically to achieve similar effects. These results are deemed more permanent than the use of botulinum toxin and injectable fillers. However, the longevity is questionable as the muscle fibers tend to regenerate and re-establish the connection, resulting in some return of muscle function and hence the rhytids. Some argue that the return of function is minimal and the need for botulinum toxin is overstated.

Special Considerations in East Asian Patients

In general, the distance between the brow and lashes of the upper eyelid is greater in Asians than in Caucasians. In addition, Asians tend to have a shallower superior orbital sulcus compared with Caucasians.

Horizontal forehead rhytids are also less common in Asians because of increased dermal thickness as well as the presence of more abundant adipose tissue in the supragaleal plane. This holds true for glabellar rhytidosis as well.

Eyebrow tattooing or micropigmentation is very popular in Asia and must be recognized at the preoperative evaluation; it is important to locate the position of the actual brow, which may have been plucked or removed. Subsequent tattooing can be utilized for scar camouflaging if necessary.

Patient Evaluation

History and Examination

It is uncommon for patients to present with complaints of droopy brows and specifically request a brow elevation. More frequently, their general complaint is looking tired, fatigued, solemn, or older, while their energy and mood do not correlate. It is not uncommon for them to ask to “have their eyes done” as they pinch the hooded skin of the upper lids. In more severe cases, they may complain of superior visual field obstruction due to the hooding or frontal tension headache secondary to frontalis over-activity in an attempt to raise the upper lid to see better. Deep static forehead rhytids frequently co-exist after many years of frontalis hyperactivity. If the medial brow drops, the patient may complain that it creates the impression of sternness or anger.

It is important to identify the specific etiology of the unwanted appearance and demonstrate this to the patient. This leads to the most direct surgical treatment. One must distinguish between dermatochalasis, brow ptosis, dehiscence of the levator aponeurosis, hyperfunctioning frontalis, facial nerve injury, and other esoteric variables. Frequently a combination of maneuvers provides the best option, with EFBL being a central staple in upper facial rejuvenation.

As with all cosmetic patients, it is important to identify those with hidden agendas or psychiatric issues during the consultation process. If their expectations are unreasonable or if they have unrealistic demands, it may be better not to operate on them.

After understanding a patient’s needs and concerns, the next part of the consultation is to establish the pathology and severity. The whole face has to be examined for proportion and harmony, including the aging process of the lower face. After rejuvenation of the upper face, the lower jowls and marionette lines will appear more dramatic in contrast. The face can be in disharmony.

It is critical to give patients a mirror during the consultation for them to point out their exact concerns. You can then use the mirror to confirm what they desire and also to demonstrate what you can achieve for them. It is important for the surgeon and patient to have similar goals and expectations.

The examination should start from top to bottom.

Hairline: The hairline is important as it determines the starting point of the upper face and can be altered during a brow lift. If the hairline is high, it makes the forehead appear longer, and further elevation may be undesirable. Conversely, a low hairline lends itself well to a brow lift procedure. A receding hairline is a major factor in determining the proper surgical option since scar exposure in the future is clearly a problem. Even women, as they age, can show signs of thinning hair in the frontal area.

Height and shape of forehead: The height and shape of the forehead determines if the EFBL method can be used. If the forehead is too long and convex, the endoscopic instruments may not be able to reach the supraorbital rim and arcus marginalis adequately, making the procedure technically very difficult. A flatter forehead with a relatively low hairline is ideal for EFBL.

Forehead and glabellar rhytids: Forehead and glabellar rhytids are assessed to determine if they are dynamic or static. Muscular hyperactivity is not uncommon, and efforts to relax the muscles are required to bring the brows back to their natural position. This is an important step before assessing the actual position of the brows and the amount of redundant upper lid skin.

Position, shape, and symmetry of eyebrows: The desired height and shape of the brow is determined with the patient in front of a mirror. It can be discussed in only general terms, or a precise calculation can be measured. The forehead is first relaxed and brows are elevated to the desired position and shape. A skin marker is then placed at the apex of the brow at the desired height. Next, the brow is released and the skin marker is allowed to slide up onto the skin of the forehead. The distance marked is the amount of brow elevation required. The same is then done on the contralateral side. Any baseline asymmetry should also be pointed out.

Amount of redundant upper eyelid skin: With the brows held at the desired height by an assistant, the amount of redundant upper lid skin is determined by pinching and then marking with a skin marker. The amount of skin to be resected should be just enough to evert the lid lashes to 90 degrees but not cause lagophthalmos.

Presence of eyelid ptosis: It is extremely important to assess for eyelid ptosis, as it can be the major contributor to the tired appearance and visual field deficit. The marginal reflex distance can be used. The ptosis may secondarily give rise to an asymmetric, relative, unilateral brow ptosis as the ipsilateral frontalis attempts to compensate and elevates the brow. Moreover, a standard brow lift will not correct the compensatory brow asymmetry.

Absence of Bell’s phenomenon and lagophthalmos: Any baseline lagophthalmos should be detected as it will likely be exacerbated following EFBL and upper blepharoplasty. Bell’s phenomenon is a normal protective mechanism for the cornea and should be present, especially if a small amount of lagophthalmos occurs postoperatively.

Lower twothirds of the face: Again, the rest of the face should be assessed to ensure facial harmony. If significant aging co-exists in this region of the face, the discrepancy can be more dramatic following surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree