Key Terms

Infantile (Juvenile) Hemangioma

Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis

Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome

Hemangioma thrombocytopenia syndrome

Hemangioma with thrombocytopenia

Pyogenic Granuloma

Lobular capillary hemangioma

Vascular tumors include all neoplasms that demonstrate endothelium-lined channels and contain red blood cells (erythrocytes). This chapter is organized so that congenital vascular lesions are discussed first, followed by benign acquired vascular lesions and, finally, malignant vascular tumors. Also included are superficial lymphangiomas with hemorrhage, which may be clinically confused with vascular tumors.

Important History Questions

How long has this lesion(s) been present?

Vascular tumors may be congenital or acquired. This is an important distinction, because some vascular tumors tend to occur in younger individuals (e.g., pyogenic granuloma) and some occur in older adults (e.g., cherry angiomata). Similarly, in general, lesions that are present for many years are less likely to be malignant.

Has the lesion changed?

A history of change or growth can be important in suggesting a malignancy. For example, early angiosarcoma of the scalp might appear initially to be flat and difficult to distinguish from a port wine stain. However, history of recent and/or rapid growth may warrant a biopsy to exclude angiosarcoma.

Have you ever been treated with radiation?

Because angiosarcomas can occur in radiation ports, even years after treatment, this is an important historical factor to ascertain and consider.

Important Physical Findings

How many vascular lesions are present?

Some vascular neoplasms usually occur as multiple lesions on the body (e.g., cherry angiomata, angiokeratomata), whereas other vascular neoplasms usually occur as solitary lesions (e.g., pyogenic granuloma, angiosarcoma).

What is the distribution of the lesions?

Most vascular neoplasms have characteristic patterns of distribution. For example, cherry angiomata often occur on the trunk. Angiosarcoma usually occurs on the head and neck, or in past radiation fields. Pyogenic granulomas usually occur on mucosal surfaces and the digits.

Are the lesions macular or palpable?

Vascular lesions can be flat (e.g., macules, patches) or demonstrate an elevated character. For example, nevus flammeus nuchae (so-called stork bite) is usually macular, whereas pyogenic granulomas and cherry angiomata are nearly always palpable. Some vascular tumors evolve from a flat to a palpable lesion. For example, infantile and juvenile hemangiomas may be flat at birth but rapidly evolve into larger palpable vascular tumors. The presence or absence of ulceration is also an important physical finding.

Are the lesions pulsatile?

Some vascular tumors, such as spider angiomata and pyogenic granulomas, are pulsatile and may demonstrate a feeder vessel on diascopy. Sometimes, the pulsatile nature of a lesion is not evident until the biopsy is performed. For example, pyogenic granulomas may manifest with pulsatile and rapid arterial bleeding when a shave biopsy is performed.

Infantile (Juvenile) Hemangioma

ICD10 code D18.0

BENIGN NEOPLASM

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of infantile hemangioma (IH), also called juvenile hemangioma or strawberry hemangioma, is not well understood. Expression of placental vascular isotopes and an increased incidence of placental abnormalities in mothers of affected children suggest a causal relationship. Infantile hemangiomas usually manifest a period of rapid growth, followed by involution, often occurring over years. IH usually reaches maximum size after 3 to 6 months of growth. A general rule of thumb is that 30% of IH involute by age 3 years, 50% by 5 years, and 70% by 7 years.

Clinical Features

- •

IH may be present at birth or may appear during the neonatal period.

- •

IH may present first as telangiectasias, pink macules, or patches or bruise-like lesions. Early lesions can mimic a port wine stain ( Fig. 32.1A ). Rarely, neonates present with well-developed lesions.

Fig. 32.1

A, Infantile hemangioma at the time of presentation. B, Fully evolved infantile hemangioma (same infant as seen in A), with partial ocular and nasal obstruction.

(Both images from the Fitzsimons Army Medical Center Collection, Aurora, CO.)

- •

Well-developed IH manifests with a red lobulated appearance, likened to a strawberry (see Fig. 32.1B ).

- •

Ulceration and hemorrhage can be identified in IH.

- •

Involution of IH manifests as decreasing size. A gray color may develop. Fully involuted IH can manifests as a white scar because telangiectasias or even atrophy may develop ( Fig. 32.2 ).

Fig. 32.2

Patient with an involuted infantile hemangioma, with residual telangiectasia, scar, and atrophy.

(From the Fitzsimons Army Medical Center Collection, Aurora, CO.)

- •

IH varies in size. Lesions may be singular or multiple.

- •

IH usually affects the skin and mucosa, but internal organs may be involved on occasion (e.g., liver, gastrointestinal tract, lungs).

- •

Patients with numerous cutaneous lesions (diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis) are at increased risk for involvement of internal organs ( Fig. 32.3 ).

Fig. 32.3

Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis. The patient also had numerous lesions in the liver.

(From the Fitzsimons Army Medical Center Collection, Aurora, CO.)

- •

IH can obstruct or partially obstruct the oral cavity or respiratory tract, or it may impair vision.

Diagnosis

- •

Early IH (macular phase) may be difficult to distinguish from port wine stains. It is often the clinical course, with rapid growth, followed by involution, that best establishes the diagnosis of IH.

- •

A punch or incisional biopsy may be needed in cases that manifest in an unusual way.

- •

Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis can be life-threatening, with mortality rates of 29% to 80%. In this circumstance, ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to evaluate for systemic disease.

Treatment

- •

Treatment of IH is controversial and depends on the site involved and degree of involvement. If possible, patients should be referred to an expert in congenital vascular lesions.

- •

Small IH are not often treated. When treatment is desired, flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser, targeting the vasculature, may be used.

- •

Systemic therapies include intralesional or systemic corticosteroids, recombinant interferon-α, or, more recently, a beta blocker (e.g., propranolol). Systemic corticosteroids may be used in life-threatening or vision-threatening IHs. Since 2008, beta blockers, especially propranolol, have been used off-label as treatment of complicated IH. Use of this drug represents a major development in the area. However, this medication should be used by those with experience in treating pediatric patients.

- •

Surgical removal is generally limited to smaller and exophytic lesions amenable to extirpation.

- •

Kasabach-Merritt syndrome requires immediate hospitalization, but treatment is not standardized.

Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome

Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome

ICD10 code D69.5

CLOTTING DISORDER

Pathogenesis

Kasabach-Merritt syndrome (KMS), occasionally referred to as hemangioma with thrombocytopenia or hemangioma thrombocytopenia syndrome, is a rare complication of hemangiomas in neonates and infants. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma are the two forms of vascular neoplasms usually associated with KMS. For unknown reasons, patients with KMS develop platelet trapping and a consumptive coagulopathy. Resultant bleeding problems can be life-threatening.

Clinical Features

- •

KMS usually presents at birth or in the neonatal or early infancy period. Almost all cases occur before 6 months of age.

- •

Patients with KMS typically have a large congenital vascular neoplasm.

- •

The vascular neoplasm often demonstrates an abrupt change in size, color, or firmness ( Figs. 32.4 and 32.5 ).

Fig. 32.4

Thrombosed tufted angioma in a patient who developed Kasabach-Merritt syndrome.

(From the William Weston Collection, Aurora, CO.)

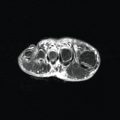

Fig. 32.5

Thrombosed deep hemangioma in a neonate who developed Kasabach-Merritt syndrome.

- •

Affected infants often develop hemorrhage and bruising at sites away from the vascular neoplasm, which include the skin and internal organs.

Diagnosis

- •

The presentation of a large congenital vascular neoplasm with abrupt change suggests concern for KMS, and this concern is augmented by hemorrhage or bruising of skin away from the vascular neoplasm.

- •

A complete blood count (CBC), with attention paid to platelet count, is important. Clotting studies should be performed emergently because clotting factors (fibrinogen) are rapidly depleted.

- •

Imaging studies such as ultrasound, MRI, or CT should be considered to investigate hemorrhage beyond the skin.

- •

In select cases, a biopsy of the vascular tumor may be considered. Thrombosis in the vascular neoplasm supports the diagnosis.

Treatment

- •

Immediate admission to a pediatric intensive care unit (ICU), preferably at a tertiary children’s facility, is important, because management often requires a multidisciplinary approach, and skilled pediatric nursing is preferred.

- •

The management of KMS is not standardized and is beyond the scope of this text. Typically, care is supportive and focuses on transfusions of fresh-frozen plasma and platelets. In select cases, treatment with anticoagulant and antithrombotic drugs may be used by experts.

- •

Surgical excision of the tumor may be curative, but urgent surgical extirpation is often made more difficult because of the bleeding diathesis. This must also be assessed by a pediatric surgeon on a case-by-case basis.

Clinical Course

KMS is a life-threatening emergency, with a mortality rate that approaches 30%.

Pyogenic Granuloma

ICD10 code L98.0

BENIGN NEOPLASM

Pathogenesis

Pyogenic granuloma, also known as lobular capillary hemangioma, is a common vascular neoplasm of unknown pathogenesis. Many cases occur at sites of trauma, and there is an increased incidence during pregnancy, suggesting a hormonal influence. Some drugs, such as oral retinoids, used in severe acne, may be associated with the development of pyogenic granulomas.

Clinical Features

- •

Pyogenic granulomas usually affect children, adolescents, and young adults.

- •

Pyogenic granulomas often evolve rapidly.

- •

Pyogenic granulomas are usually singular, but multiple lesions can develop.

- •

Although the distribution is highly variable, the face, fingers, lips, and gingivae represent common sites.

- •

Pyogenic granulomas may develop in preexisting hemangiomas or port wine stains.

- •

Pyogenic granulomas usually present as red to violaceous exophytic papules that may be pedunculated ( Figs. 32.6–32.9 ).