Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

The incidence of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is as high as 1 in 6,000 live births.1,2 It occurs with equal frequency in males and females and in different races and ethnicities. Hereditary transmission is evident in approximately one-third of patients. Sporadic disease occurs in about two-thirds of patients, and this is attributed to de novo mutations.3

Etiology and Pathogenesis

TSC is caused by mutations in a tumor suppressor gene, either TSC1 or TSC2.3 Mutations in TSC2 are observed in about three-fourths of patients, and even more commonly in de novo cases.4,5 Patients with mutations in TSC2 tend to exhibit a more severe phenotype.4–7

TSC1 maps to chromosome band 9q34. The 8.6-kb full-length transcript encodes a protein called hamartin or TSC1.8 TSC2 maps to chromosome band 16p13.3. The 5.5-kb transcript encodes a protein called tuberin or TSC2.9 Immediately adjacent to TSC2 on chromosome 16 is PKD1, the gene mutated in polycystic kidney disease. Some patients with TSC have severe, early-onset renal cystic disease, and most of these patients have a contiguous deletion of TSC2 and PKD1.10

Typical of mutations in tumor suppressor genes, the mutations observed in patients with TSC are inactivating mutations located anywhere along the sequence of TSC1 or TSC2. Consistent with Knudson’s two-hit hypothesis, most TSC tumors show a second somatic mutation that inactivates the wild-type allele.11,12 TSC1 and TSC2 form a complex that inhibits signaling through the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway (Fig. 140-1). Loss of TSC1/TSC2 function leads to increased mTOR signaling and increased cell growth. Rapamycin is a drug that inhibits mTOR and may be useful for the treatment of internal tumors in TSC.13

Figure 140-1

Molecular pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). A. An example is shown in which a mutation in TSC2 is passed from the father (red square) to the son (red square), whereas the mother (white circle) and another son (white square) are unaffected. B. Skin lesions are observed in the son at the indicated locations. C. A cell from the mother shows two normal alleles for TSC2 on chromosome band 16p13.3. A cell from the son shows the TSC2 mutation inherited from his father. A tumor from the son has this germ-line mutation and a “second-hit” mutation, detectable as loss of heterozygosity at this locus, that inactivates the other allele. D. TSC2, in a complex with TSC1, is a guanosine triphosphatase-activating protein, converting active Ras-homolog enriched in brain (Rheb) guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to inactive Rheb guanosine diphosphate (GDP). Rheb GTP activates mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a kinase that increases protein translation and cell growth, so TSC2 normally acts to inhibit cell growth. Loss of TSC2 function in tumors results in increased levels of Rheb GTP, activation of mTOR, and increased cell growth.

Clinical Findings

The diagnosis of TSC is based on clinical criteria categorized as major or minor features (Table 140-1).14,15 Cutaneous and oral lesions comprise 4 of 11 major features and 3 of 9 minor features. Major features are thought to have a high degree of specificity for TSC, whereas minor features are less specific or substantiated. No single feature is present in all patients, and no feature is specific for TSC. Genetic testing can be offered and may be important in particular situations (see Section “Molecular Diagnosis”).15

Major Features |

|

Minor Features |

|

The medical and family history taking should include questions about seizures, learning disability, behavioral disorders, visual problems, and tumors of the brain, heart, kidneys, lungs, and skin. Determining the ages of onset of skin lesions and their subsequent changes may assist in discriminating TSC skin lesions from similar-appearing non-TSC skin lesions. Many TSC skin lesions are not present at birth, but appear later at ages typical for the lesion.16 For example, infants show multiple hypomelanotic macules but not angiofibromas or ungual fibromas. Adults may have multiple angiofibromas and ungual fibromas, but hypomelanotic macules may have faded or disappeared.

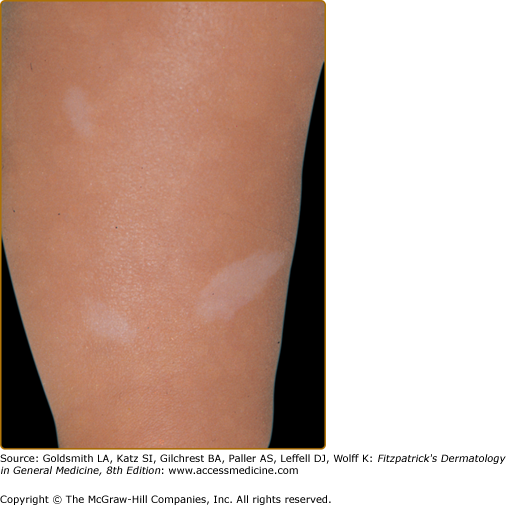

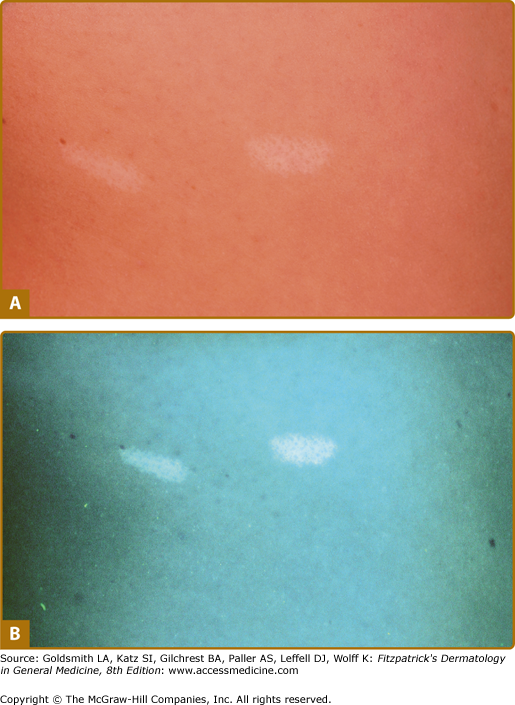

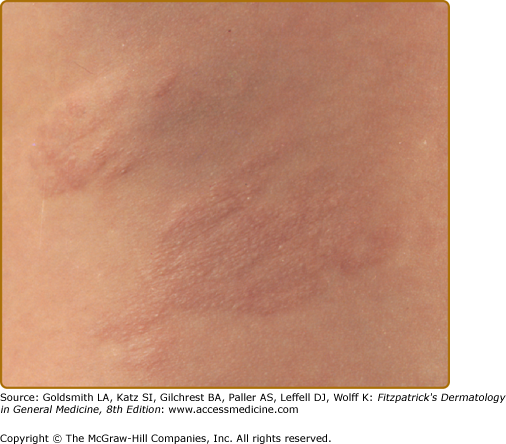

Hypomelanotic macules (Fig. 140-2) are observed in over 90% of children with TSC.4,17–21 They are often present at birth or appear within the first few years of life and may fade or disappear in adulthood. The ultraviolet light of a Wood’s lamp is used to improve detection, especially in lightly pigmented individuals22 (Fig. 140-3).

Hypomelanotic macules typically measure 0.5–3.0 cm in diameter. They are off-white and not completely depigmented as in vitiligo.23 Some are oval at one end and taper to a point at the other. Such lesions are called ash-leaf spots because of their resemblance to the leaf of the European mountain ash.24 They number from 1 to over 20. They can be located anywhere on the body but tend to occur most often on the trunk and buttocks. When located on the scalp, they cause poliosis.17

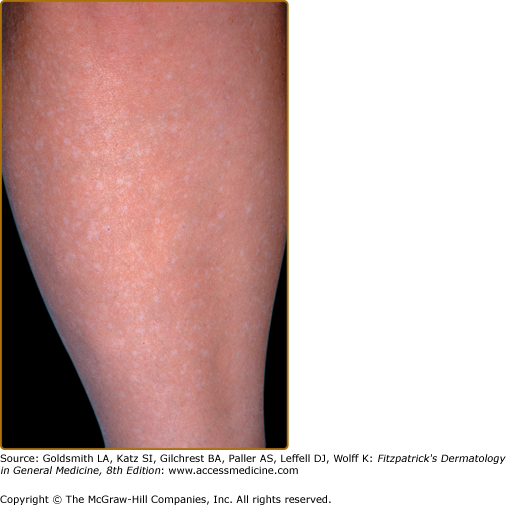

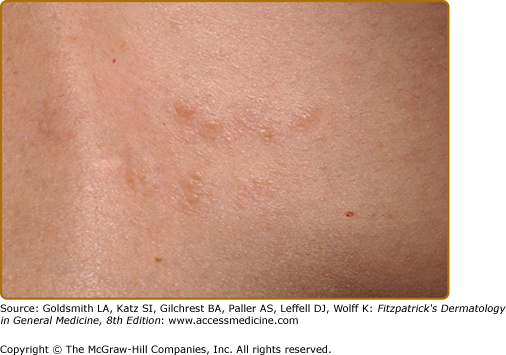

Three or more hypopigmented macules constitutes a major feature for the diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis. One or two, and in rare individuals up to three, hypomelanotic macules occur in 4.7% of the general population.25 A less common type of hypopigmentation is the “confetti” skin lesion (Fig. 140-4), which is considered a minor feature for diagnosis. It typically occurs on the legs below the knees or on the forearms, and consists of multiple hypopigmented macules 2–3 mm in diameter.17,24

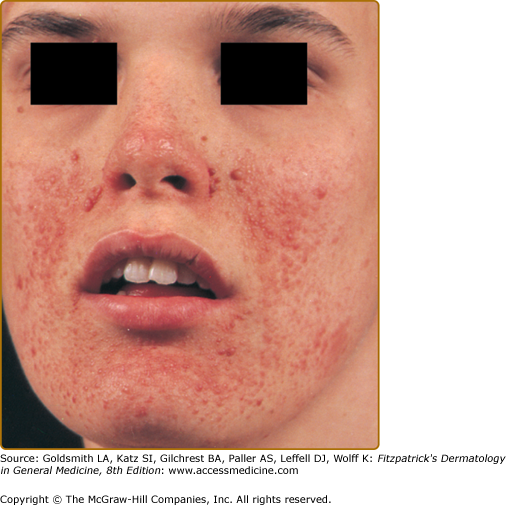

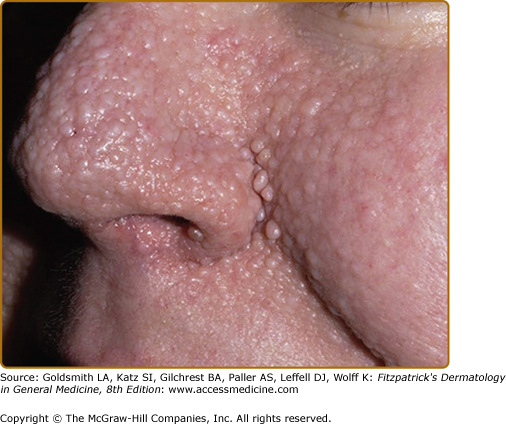

Angiofibromas appear at 2–5 years of age and eventually affect 75% to 90% of patients.4,17,20,21 These 1–3 mm in diameter pink to red papules have a smooth surface (Fig. 140-5). They may be hyperpigmented, especially in individuals with darker pigmentation. They occur on the central face and are often concentrated in the alar grooves (see eFig. 140-5.1), extending symmetrically onto the cheeks and to the nose, nasal opening, and chin, with relative sparing of the upper lip and lateral face. Sometimes lesions occur on the forehead, scalp, or eyelids. They may number from 1 to over 100. Lesions may coalesce to form large nodules, especially in the alar grooves.17,20,22 Angiofibromas are unilateral in rare cases and may indicate a segmental or mosaic defect.26–29

The development of papules may be preceded by mild erythema that is intensified by emotion or heat. During puberty, angiofibromas may grow in size and number. During adulthood they tend to be stable in size, but redness may gradually diminish.22

Angiofibromas must be multiple to be counted as a major feature. A solitary angiofibroma is clinically and histologically indistinguishable from the fibrous papule that occurs sporadically as a single lesion in the general population.30 Multiple angiofibromas are also observed in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1,31–33 and as an unusual finding in Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome.34

The forehead plaque may be congenital or show gradual development over years.17,35 It is present in 20% to 40% of patients.4,17,20 It is an irregular, soft to firm, connective tissue nevus with the color of the normal surrounding skin, red, or hyperpigmented in darkly pigmented individuals (Fig. 140-6). The plaque can also be found on the scalp, cheeks, and elsewhere on the face and is therefore sometimes referred to as a fibrous facial plaque. The forehead plaque is grouped together with angiofibromas as a major feature for diagnosis.14

The shagreen patch is observed in approximately 50% of patients.4,17,20,21 It may be present in infancy but usually becomes apparent later. It is a firm or rubbery irregular plaque ranging in size from 1 to 10 cm (Fig. 140-7). The surface may appear bumpy with coalescing papules and nodules, or the patch may have the surface appearance of an orange peel. The color may be that of the surrounding skin, or it may be slightly pink or brown. There may be scattered smaller oval papules with or without a larger plaque (see eFig. 140-7.1). The most common locations are on the lower back and buttocks; the patch is found less commonly on the thighs.22

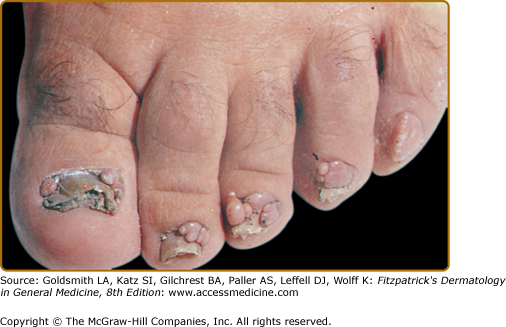

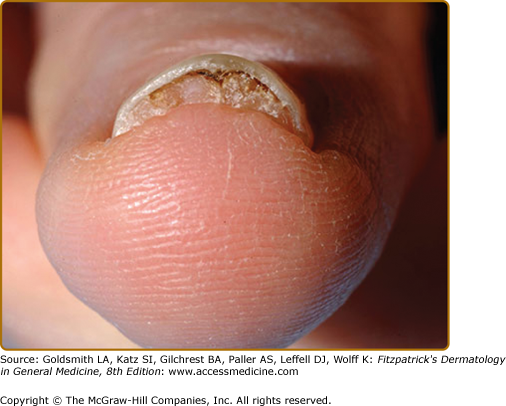

Ungual fibromas, also known as Koenen’s tumors, usually appear after the first decade and eventually affect up to 88% of adults with TSC.20 They are more common on the toes than on the fingers.36

Ungual fibromas measure 1 mm to 1 cm in diameter. They arise from under the proximal nail fold (periungual fibromas) and under the nail plate (subungual fibromas). Periungual fibromas are red papules and nodules that are firm, pointed, and hyperkeratotic, or soft and rounded (Fig. 140-8). They press on the nail matrix and cause a longitudinal groove, and sometimes a groove forms without an evident papule20,36 (see eFig. 140-8.1). Subungual fibromas can be seen through the nail plate as red or white oval lesions or as red papules emerging from the distal nail plate, causing distal subungual onycholysis (see eFig. 140-8.2). In addition to ungual fibromas, TSC patients may develop “red comets” (subungual red streaks), splinter hemorrhages, and longitudinal leukonychia.36

Presence of a nontraumatic ungual fibroma is a major feature for diagnosis of TSC.14 Solitary lesions (also termed acral or acquired digital fibrokeratomas) are also observed in the general population, especially after nail trauma.37 Multiple acral fibromas with a myxoid stroma were reported in one patient with familial retinoblastoma.38

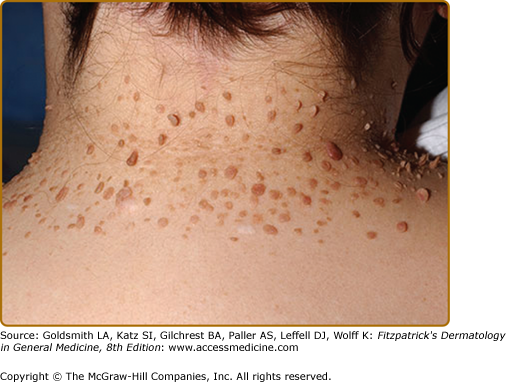

Molluscum fibrosum pendulum (skin tags) is the name given to multiple fibroepithelial polyps in TSC. These range from soft pedunculated papules to larger firm pedunculated nodules located on the neck, axillae, trunk, and flexures (see eFig. 140-8.3). They can be skin colored or hyperpigmented.17 Skin tags are common in the general population, so these are not useful for diagnosis. Miliary fibromas are patches of multiple minute papules, usually on the neck or trunk that appear like “gooseflesh.”22 Pachydermodactyly is a benign thickening of the proximal fingers that has been observed in a few patients with TSC.36,39,40

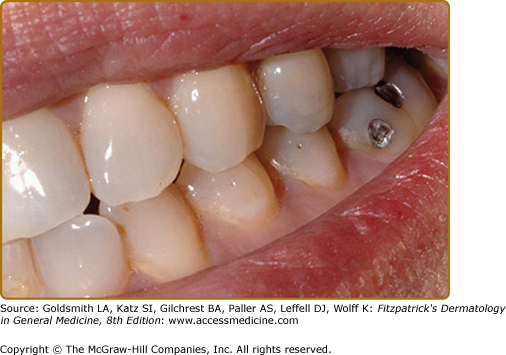

Multiple pits of the dental enamel are observed in up to 100% of TSC patients.41–44 These pits can be tiny pinpoint lesions or larger crater-like lesions (see eFig. 140-8.4). They occur on both deciduous and permanent teeth. The identification of these lesions is enhanced by using a dental plaque stain. Dental pits can also be seen in the general population, albeit with lower prevalence and at lower numbers than in TSC.41 The presence of multiple dental pits is a minor feature for diagnosis.14

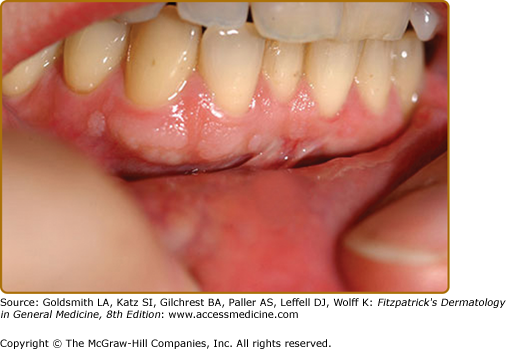

Approximately 50% of TSC patients have oral fibromas20 (see eFig. 140-8.5). These sometimes occur in the first decade but are more common in adulthood.45 They are most common on the gingivae, but also occur on the buccal and labial mucosa, hard palate, and tongue.45 Some patients have diffuse gingival overgrowth. Gingival overgrowth is a common side effect of anticonvulsants, especially phenytoin and cyclosporine, but gingival overgrowth can be observed in TSC even in patients not treated with anticonvulsants or immunosuppressive agents.45,46 Gingival fibromas are a minor feature for diagnosis.14 Oral fibromas in the general population are typically single and form at sites of trauma, usually on the tongue or buccal mucosa.47

Tuberous sclerosis can affect almost any organ. Only one-third of patients have the classic triad of seizures, mental retardation, and angiofibromas.

Cerebral lesions include cortical tubers, subependymal nodules, and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas. Cerebral lesions may manifest as seizures, cognitive disability, and behavioral disorders. Seizures occur in approximately 80% of patients, with onset common in the first 2 months and usual by the first 2 years of life. Seizures are most likely infantile spasms but can be all types except pure absence (classic petit mal).48 Seizures are controlled with antiepileptic drugs. A ketogenic diet can decrease seizures and mTOR inhibitors may also prove to be useful in reducing seizures.49,50 Epilepsy surgery may be required for seizures intractable to anticonvulsant therapy.51,52

Learning disability tends to occur in patients with seizures, but many children with seizures have no obvious neurologic impairment. The extent of mental disability ranges from mild to profound. Individuals with normal intelligence may have specific deficits in attention, executive control, and memory.53 Behavioral disorders include autism, attention deficit disorder, hyperactivity, aggressive behavior, impulsivity, anxiety, and sleep disorders.7,53,54

Subependymal giant cell astrocytomas occur in 6% to 14% of individuals with TSC. They may increase intracranial pressure and cause headache, vomiting, and bilateral papilledema.55

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are observed in 50% to 70% of infants with TSC.56 These neoplasms are often asymptomatic and spontaneously regress, but they may cause fetal hydrops and stillbirth or heart failure shortly after birth.57,58 Cardiac rhabdomyomas may cause dysrhythmias, commonly Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, noticed in utero or in the first year of life in TSC patients.57–59

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree