Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is a channel created within the liver parenchyma to divert blood from the portal circulation to the systemic circulation. The aim of TIPS is to reduce portal venous pressure and treat the complications of portal hypertension, such as refractory bleeding varices and ascites. The shunt is created percutaneously between the intrahepatic portal vein and a hepatic vein through internal jugular venous access, by minimally invasive endovascular techniques under image guidance. The TIPS procedure is now widely accepted as an alternative to surgically created portosystemic shunts, which are associated with greater morbidity and mortality.

TIPS can also serve as a bridge to liver transplantation and offers the benefit of not altering the anatomy of the portal and mesenteric veins. Preservation of this anatomy reduces operative risk during subsequent transplantation. Other advantages of TIPS include controlled decompression of portal hypertension, thus minimizing the risk of hepatic encephalopathy, and the ability to embolize and sclerose bleeding varices and other competing portosystemic shunts at the time of placement.

There is level 1A evidence by systematic review of randomized controlled trials to support TIPS placement for the management of variceal bleeding refractory to endoscopic management and ascites refractory to medical management, which are the most common indications for TIPS placement.1

Clinical benefits of TIPS creation have been reported for other indications with limited evidence. A comprehensive list of indications and contraindications for the TIPS procedure and their associated level of evidence are listed in Table 1.1,2

Details of prior upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleed, findings of upper GI endoscopy to exclude other causes of nonvariceal upper GI bleeding, history of prior endoscopic management of bleeding varices, and frequency of paracentesis or thoracentesis should be obtained. Specific attention should be paid to the history of recent changes in mentation or memory loss indicating encephalopathy.

Patients with the preexisting encephalopathy and bleeding gastric varices should be evaluated for balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) of gastric varices because TIPS can worsen encephalopathy.

History of hepatobiliary disease and prior biliary and GI surgery should be documented. Prior surgeries may alter anatomy and can increase the complexity of TIPS placement.

History of prior liver resection or liver transplantation and the details of altered anatomy from these surgeries including the type of venous anastomosis must be obtained. Prior liver resection or transplantation is not a contraindication for TIPS. However, knowledge of altered portal and hepatic venous anatomy is essential for proper procedure planning.

History pertaining to heart disease, deep vein thrombosis, prior pulmonary embolism and pulmonary hypertension require additional preprocedural cardiac workup because pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure are contraindications to TIPS.

History of prior pancreatitis with splenic vein thrombosis may result in focal left upper quadrant portal hypertension and gastric varices. TIPS is not indicated for isolated gastric varices from splenic vein occlusion. Transhepatic recanalization of the splenic vein, BRTO, partial splenic arterial embolization, or splenectomy should be considered to treat this condition.

Focal physical examination is performed with special emphasis on assessing the patient’s nutritional status, jaundice, lower extremity edema, splenomegaly, ascites, hydrothorax, and encephalopathy.

Detailed and extensive discussion of the risks and benefits of the procedure (in particular encephalopathy) should be carried out with the patient and the family.

Complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel, and coagulation profile are essential to evaluate the need for correction of thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy and to evaluate the severity of liver disease.

Table 1: Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Indications and Contraindications

Indications (level of evidence)

Secondary prevention of variceal bleeding (1A)

Refractory ascites (1A)

Refractory acute variceal bleeding (1B)

Hepatorenal syndrome (1B)

Portal hypertensive gastropathy (2B)

Refractory hepatic hydrothorax (4)

Budd-Chiari syndrome (4)

Hepatic veno-occlusive disease (4)

Hepatopulmonary syndrome (4)

Absolute contraindications

Primary prevention of variceal bleeding

Polycystic liver disease

Severe hepatic failure

Severe right heart failure (RA pressure >20 mmHg)

Severe pulmonary hypertension (mean >45 mmHg)

Uncontrolled systemic infection or sepsis

Unrelieved biliary obstruction

Severe tricuspid regurgitation

Relative contraindications

Uncorrectable hepatic encephalopathy

Hypervascular liver tumors

Portal vein thrombosis

Thrombocytopenia of >20,000/cm3

Uncorrectable severe coagulopathy

Moderate pulmonary hypertension

Complete hepatic vein obstruction

RA, right atrial.

A Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score that does not include additional points for cause of liver disease is widely accepted to predict survival following TIPS placement.3 A MELD score of greater than 18 is associated with significantly higher mortality rate at 3 months following TIPS.1

Preprocedural imaging of the liver and the portal venous system with ultrasound or other imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to document patency of the hepatic veins, portal vein, and intrahepatic portal branches should be performed. Chronic occlusion of the portal vein is a relative contraindication of TIPS placement. Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI scans of the liver and portal venous system allow greater understanding of the spatial relationship between the hepatic veins and intrahepatic portal venous branches and should be considered for planned TIPS creation. Cross-sectional imaging with CT and MRI are especially helpful for planned TIPS in patients with prior liver resections.

In patients with history of long-term central venous access catheters, ultrasound examination of the internal and external jugular veins bilaterally should be considered.

Electrocardiogram (EKG) and surface echocardiography should be performed to assess cardiac function and right heart pressures if there is any suspicion of associated heart disease on history and physical examination.

Preprocedure liver biopsy is not essential before TIPS placement. However, if prior liver biopsy is available, it may be useful to differentiate presinusoidal and postsinusoidal causes of liver disease.

Evaluation of ascitic fluid should be performed in patients with clinical suspicion of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

TIPS is contraindicated in the presence of significant intrahepatic biliary dilation. However, TIPS can be performed safely following decompression of the bile ducts.

Patients with hepatitis C liver disease should be tested for α-fetoprotein elevation, and if elevated, should have cross-sectional imaging when feasible to rule out intrahepatic tumors.

It is common practice to type and crossmatch for blood products prior to TIPS.

Risks and benefits of TIPS placement are thoroughly discussed with the patient and family, and informed consent is obtained in the clinic setting. For emergent procedures, the family should be made aware of the morbidity, mortality, and risk of encephalopathy associated with the procedure.

Laboratory data and all previous imaging studies should be reviewed to access the extent of liver, renal, and cardiac disease present; to document patency of the portal venous system; and to identify altered anatomy from prior surgeries.

Preexisting thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy should be corrected. Blood products should be made available at the blood bank.

Patients with active upper GI variceal bleeding should have Blakemore tubes placed for balloon tamponade of varices before transfer to interventional radiology. TIPS can be performed while the esophageal and gastric balloons are inflated. However, the authors recommend deflation of balloons during post-TIPS placement splenoportogram to assess variceal filling and the need for embolization of varices.

Thoracentesis and paracentesis followed by recommended albumin infusion is performed the evening prior to the procedure in elective cases.

Preprocedural prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics are recommended.

Patient is placed supine on the angiographic table.

Preliminary ultrasound examination of the internal and external jugular veins should be performed bilaterally.

Following the initiation of conscious sedation or induction of general anesthesia, the planned jugular venous access site is prepped and draped in sterile fashion. Prepping the right upper quadrant (RUQ) and lower abdomen is recommended if paracentesis or transhepatic portal vein access for guidance is anticipated.

Paracentesis or thoracentesis should be performed first if there is significant ascites or hydrothorax. Significant ascites reduces fluoroscopic visibility during the procedure and at the same time increases the radiation dose to the patient. Displacement of the liver due to hydrothorax or massive ascites may also result in unfavorable anatomy for portal vein access.

An arterial line for continuous pressure monitoring during the procedure is indicated following large volume paracentesis in patients with active GI bleeding or hemodynamic instability.

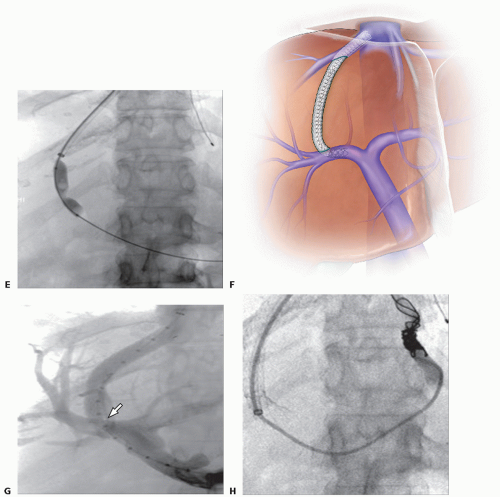

TIPS is most commonly performed through right internal jugular vein access. Using standard Seldinger technique, access to the right internal jugular vein is obtained with ultrasound guidance. Over a guidewire, the access is dilated and a 10-Fr dedicated vascular sheath is placed into the inferior vena cava (IVC).

Some practitioners prefer the use of the left internal jugular vein, as it may provide more stable access to the right hepatic vein. Alternatively, the right and left external jugular veins can be used.

In cases of superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction, right and left common femoral venous access can be used for recanalization of the SVC to facilitate more standard venous access from above. Common femoral access can also be used directly for TIPS creation in extreme situations.

Care is taken with guidewires, dilators, and sheaths to prevent cardiac dysrhythmias and right atrial perforation while crossing the right atrium.

Right atrial and IVC pressures are not routinely obtained unless there is a clinical reason such as history of cardiac or pulmonary disease.

Selection of an appropriate vein of suitable diameter is important. TIPS creation through the right hepatic vein is most common. A standard nonglide, 5-Fr appropriately shaped catheter (based on prior imaging) is then advanced through the sheath into the mid-IVC. As the catheter is withdrawn, the hepatic vein is cannulated.

When the right hepatic vein is considered not suitable due to smaller caliber or other anatomic reason, TIPS can be performed through the middle or even left hepatic veins.

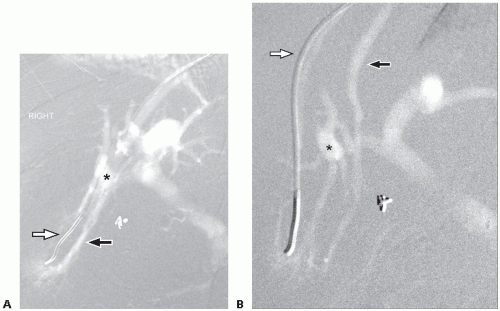

It can be difficult to distinguish between the right and middle hepatic veins (MHVs), but it is important to do so. When a wedged hepatic venogram is performed in a steep right anterior oblique (RAO) projection (see Visualization of the Portal Venous System), the right hepatic vein will be posterior and the MHV will be anterior to the right branch of portal vein (FIG 1).

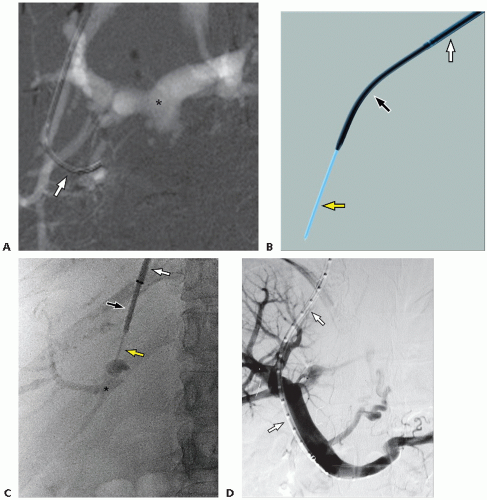

Indirect visualization of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic portal veins during the TIPS procedure can dramatically decrease procedure time. This can be done in multiple ways.

Most commonly, wedged portography using contrast or carbon dioxide (CO2) gas is performed (FIG 2A). CO2 gas is an excellent agent for imaging of the hepatic veins, portal veins, and varices because CO2 can easily flow through the venules and sinusoids due to its low viscosity. CO2 is the contrast agent of choice for wedged hepatic venography and in patients with associated renal impairment. However, use of CO2 is contraindicated in patients with right-to-left intracardiac shunting and should be used with caution in patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome.

The right hepatic vein catheter is wedged into a central hepatic venule. Wedge hepatic venogram and indirect portogram is then performed with injection of CO2 gas or contrast. CO2 or contrast will flow through the sinusoids to the portal side resulting in filling of the main portal vein and its branches. Peripheral wedging should be avoided to prevent extravasation and even capsular perforation. Imaging should be performed in both anteroposterior (AP) and steep RAO projections to properly assess the anatomic relation of the hepatic vein and the right branch of the portal vein (FIG 1).

Similarly, the intrahepatic portal branches can also be visualized using an occlusion balloon catheter. In this method, the 5-Fr catheter is exchanged over a guidewire for an occlusion balloon catheter. The balloon catheter is inflated in a branch of the hepatic vein and not wedged. The balloon is inflated to obstruct venous outflow from the segment. The injection pressure of CO2 is dissipated in a larger segment of liver minimizing complications and with better filling of the portal branches and the main portal vein.

Occasionally, wedge portography may fail to visualize portal vein especially in patients with veno-occlusive disease and intrahepatic portal vein branch thrombosis.

When indirect visualization of the portal vein is unsuccessful, direct visualization can be attempted (see “The Difficult Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt”).

Under ultrasound guidance, a 22-gauge needle can be inserted percutaneously into the intrahepatic portal venous system for injection of contrast or CO2. This method will require embolization of the parenchyma traversed during portal vein access at the end of the procedure with Gelfoam or coils to ensure hemostasis.

Other methods include percutaneous cannulation of a paraumbilical vein or trans-splenic access to the portal vein, both of which also require embolization of the access tract at the conclusion of the procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree