The aging appearance of the lower eyelids is multifactorial, involving changes in the skin, orbital fat, orbicularis muscle, soft tissue of the midface, and tear trough. The extent of these changes differs in each case and happens in a background of volume loss that occurs with facial aging. We present the indications, advantages, and technique for volumizing transcutaneous lower blepharoplasty with fat transposition. The absolute and relative contraindications to transcutaneous surgery are discussed, and surgical details of transconjunctival blepharoplasty with fat repositioning and autologous fat grafting as alternative approaches are included.

Key points

- •

Lower blepharoplasty requires precise diagnosis and appropriately directed surgical approach.

- •

Optimal rejuvenative results are achieved with transcutaneous lower blepharoplasty when orbicularis muscle is preserved and appropriate suspensory maneuvers are performed in conjunction with fat transposition or autologous fat grafting.

- •

Contraindications to the transcutaneous technique include a negative vector orbit, orbicularis muscle weakness and excess lower eyelid laxity, in which case a transconjunctival approach is preferred.

Introduction

Even though a patient presenting for eyelid rejuvenation may be displeased with the changes in the periorbital tissues creating a tired or baggy eyelid look, they are unwilling to trade improvement in this look for a change in the natural contour of their eyes. Patients and surgeons fear any distortion of the natural shape and aperture of the eye. This is especially true for patients, as they see too many postoperative friends, family members, or people on the street who look like they have had plastic surgery on their eyelids. Results often show “round” small eyes, distortion of the lateral canthus with a “cat eye” appearance, or ectropion. It is anxiety provoking for the surgeon, as these undesired changes seem to be difficult to control, with the same technique giving a very different outcome in different patients.

I have performed more than 3000 blepharoplasties and I have learned the hard way. There are techniques that I was taught that I now avoid. I have added techniques described more recently and have advanced the field of peri-orbital rejuvenation with modified techniques. Although these changes in technique are important to creating better outcomes and happier patients, I believe that there are 2 other considerations crucial to better blepharoplasty outcomes. First, it is of the utmost importance to choose the right surgical approach based on the patient’s anatomy. An example of not matching the technique to the anatomy is performing a lower eyelid orbital fat reduction in a patient with a proptotic negative vector eye that creates deep set hollowed eyes that are not rejuvenated but actually more tired in appearance. The second is respecting the patient’s eyelid appearance as it existed in youth.

Because there are so many variables, and today so many techniques, it is important to have a clear understanding of the patient’s anatomy now and in youth, what their desires are, and what pitfalls might exist with a chosen approach. Of all the procedures we perform as aging face surgeons, there is more art and judgment required when treating the eyelids than any other area in the face.

Aging lower eyelid anatomy

The lower eyelid is formed by 3 lamellae: the anterior, middle, and posterior lamellae. The anterior lamella is the skin and orbicularis oculi muscle, the middle lamella is the tarsal plate and orbital septum, and the posterior lamella is the conjunctiva and the lower lid retractors. The orbicularis oculi muscle is composed of 2 parts: the outer orbital and inner palpebral portion. The palpebral portion contains a pretarsal component and a preseptal component. The upper and lower pretarsal components of the orbicularis oculi muscle join medially and insert onto the lacrimal crest as the medial canthal tendon. The 2 lateral components of the pretarsal orbicularis join together to form the lateral canthal tendon, which inserts onto the Whitnall tubercle. Immediately deep to the preseptal orbicularis oculi muscle is the orbital septum, a continuation of the orbital periosteum. The lower eyelid retractors fuse with the orbital septum approximately 5 mm inferior to the inferior-most aspect of the tarsal plate.

Orbital fat is contained within the orbital septum. The lower eyelid has 3 fat pads: medial, central, and lateral. The inferior oblique muscle divides the medial and central fat compartments and is an important anatomic marker to identify and preserve. The medial fat pad is distinct in that it contains denser whiter-colored fat. Both genetics and aging play a role in the size of these fat pads, and these fat pads do not fluctuate in size with changes in body habitus.

Age-related changes in the periorbital area are multifactorial and are best understood by the contributing parts. The aged periorbital appearance is the result of cumulative changes in skin texture, volume depletion, loss of elasticity, formation of rhytids, drooping of the skin, and ptosis. This milieu of changes result in the characteristic findings of the aged lower eyelid, one that is marred by dermatochalasis, pseudoherniation of the orbital fat, malar festooning, and atonia of the lower eyelid that affects lid and canthal position.

Just like in upper eyelid aging, there are patients who accumulate more soft tissue and those who lose soft tissue. This is manifested as pseudo-herniated fat compartments creating lower eyelid bag. Many patients develop devolumization of the lower eyelid with age and have no need for correction or reduction of the fat compartments. In fact, those with devolumization will need augmentation with autologous fat grafting to complete their eyelid rejuvenation.

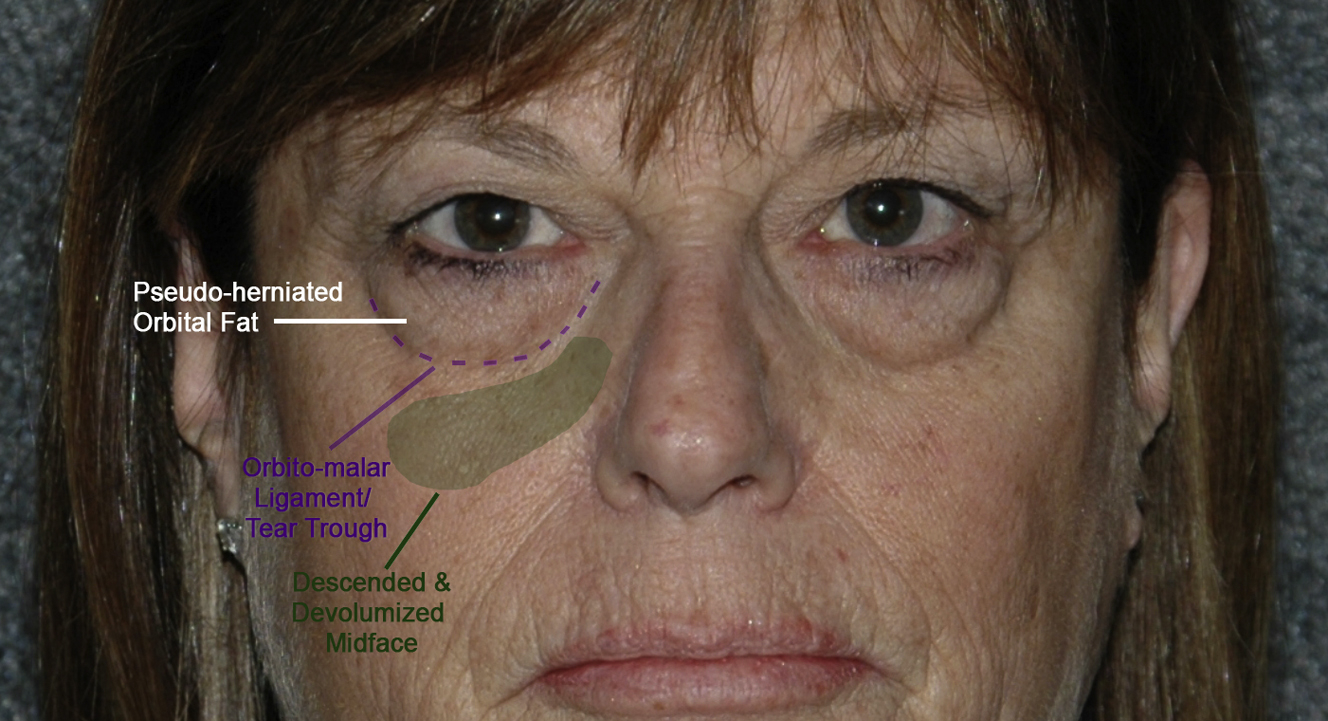

The tear trough is an area of particular concern in the aging eyes. The tear trough is the concave area caudal to the inferior orbital fat. First described as the nasojugal fold by Duke-Elder and Wybar in 1961, the modern day name “tear trough deformity” was coined in 1969 by Flowers when it was observed that tears would track down this dependent area. The etiology of the tear trough deformity appears to be multifactorial. Recent evidence suggests that the tear trough occurs as a result of skin tethering by an osteocutaneous ligament, situated between the origins of the palpebral and orbital parts of the orbicularis muscle. This ligament extends from the level of the insertion of the medial canthal tendon to the line of the medial pupil, where it continues laterally as the orbitomalar retaining ligament. This tethering effect is exacerbated with aging due to increasing bulge of orbital fat from above, and atrophy with descent of the malar fat below ( Fig. 1 ). This ligament also tethers redundant orbicularis muscle that develops with age, creating malar festoons and mounding.

The midface is an important yet often overlooked contributing factor to periorbital aged appearance. Gravitational descent and volume depletion of the midface indirectly affects the periorbita and plays a significant role in the aged appearance of the lower lids. The midface descends with synchronous deflation of the suborbicularis oculi fat creating a deepening of the tear trough. The ptotic mid face creates another bulge inferior to the tear trough.

Pseudoherniation and apparent orbital fat excess accentuates the tear trough, volume loss and hollowing in the infraorbital and lateral orbital areas, and a midface bulge, creating a double convexity of profile view ( Fig. 2 ).

Addressing the tear trough is important for successful rejuvenation of the lower periorbital area, which is why we recommend release of the orbitomalar retaining ligaments to allow for both redraping excess orbicularis muscle as well as volumizing the depth of the tear trough with transposed orbital fat. This ligament also tethers redundant orbicularis muscle that develops with age, creating malar festoons and mounding.

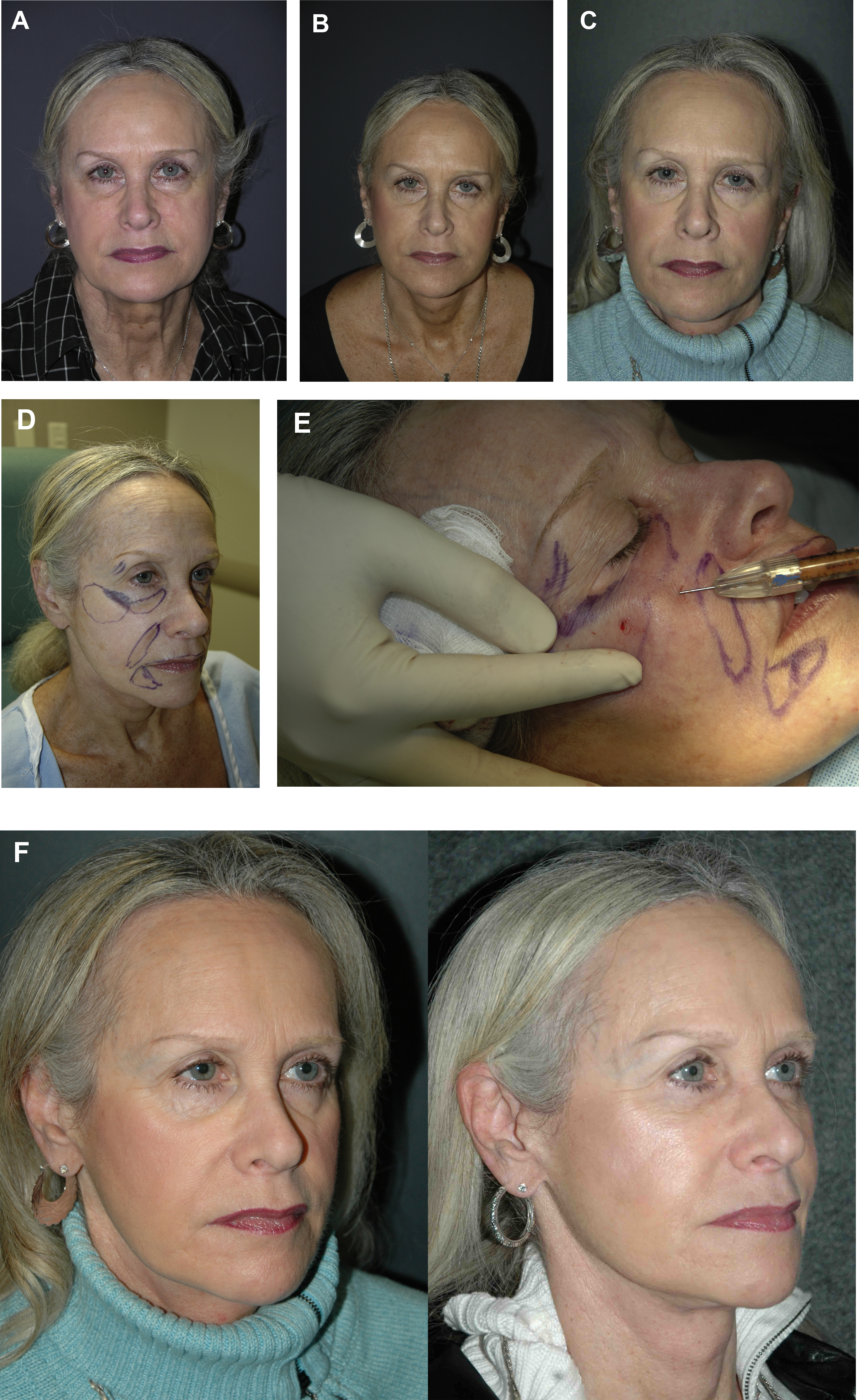

Surgical techniques for rejuvenation of the lower eyelid

There are 2 approaches to the lower eyelid I use, both involve volumizing the tear trough. I do not perform simple reductive blepharoplasty with fat pad removal anymore, as the patients will often need volume supplementation as early as 5 years after surgery, with continued volume loss with age, which magnifies the soft tissue deficit in the lower eyelid ( Fig. 3 ). Even in younger patients who have less volume loss, I will transpose fat to give them more volume reserve for the future ( Fig. 4 ).

One approach uses a transposition of excessive pseudoherniated lower eyelid orbital fat pads into the area of the tear trough, and the other approach adds supplemented autologous fat to the tear trough area in those patients who have a deflated orbit with modest fat pad volume. A deflated orbit also occurs in patients who had a reductive lower blepharoplasty performed prior. Many surgeons will combine removal of orbital fat pads with autologous fat injections to the tear trough. It is my preference to use the orbital fat because it is a vascularized fat flap and it always maintains its volume when transposed. Autologous fat is a free graft and has a failure rate of 20% to 25% with either incomplete or no graft take, so it is less predictable. With that being said, when there is no fat to transpose, autologous fat is the solution.

I use both a transcutaneous and transconjunctival approach to fat transposition and have specific indications for both. A transcutaneous approach to the fat in the lower eyelid in the wrong patient with contraindicated anatomy will increase the patient’ risk for lower eyelid malposition and ectropion. It is our experience that even small changes in eyelid shape are extremely distressing to the patient and change their perception of their facial identity. In my practice, I have gone from performing transcutaneous blepharoplasty in 90% of my patients to 50% today to decrease the risk. It has become more of an issue in the past 5 to 7 years, with patients’ use of selfie cameras on their cell phones that magnify even slight changes in eyelid shape. We are not talking about severe lateral canthal rounding or ectropion, but small changes. A recent study showed that selfie cameras increase nasal distortion by 30%. When performing a transconjunctival approach I will still address skin excess with a skin pinch and tighten the orbicularis by tightening it with plication of the muscle to the orbital periosteum as described in the following.

Preoperative evaluation: indications and contraindications

Preoperative planning is lauded by some as the most important aspect of blepharoplasty, and is vital to achieving successful outcomes. , The eyes are a focal point of the face and serve as the natural transition between the upper and middle face.

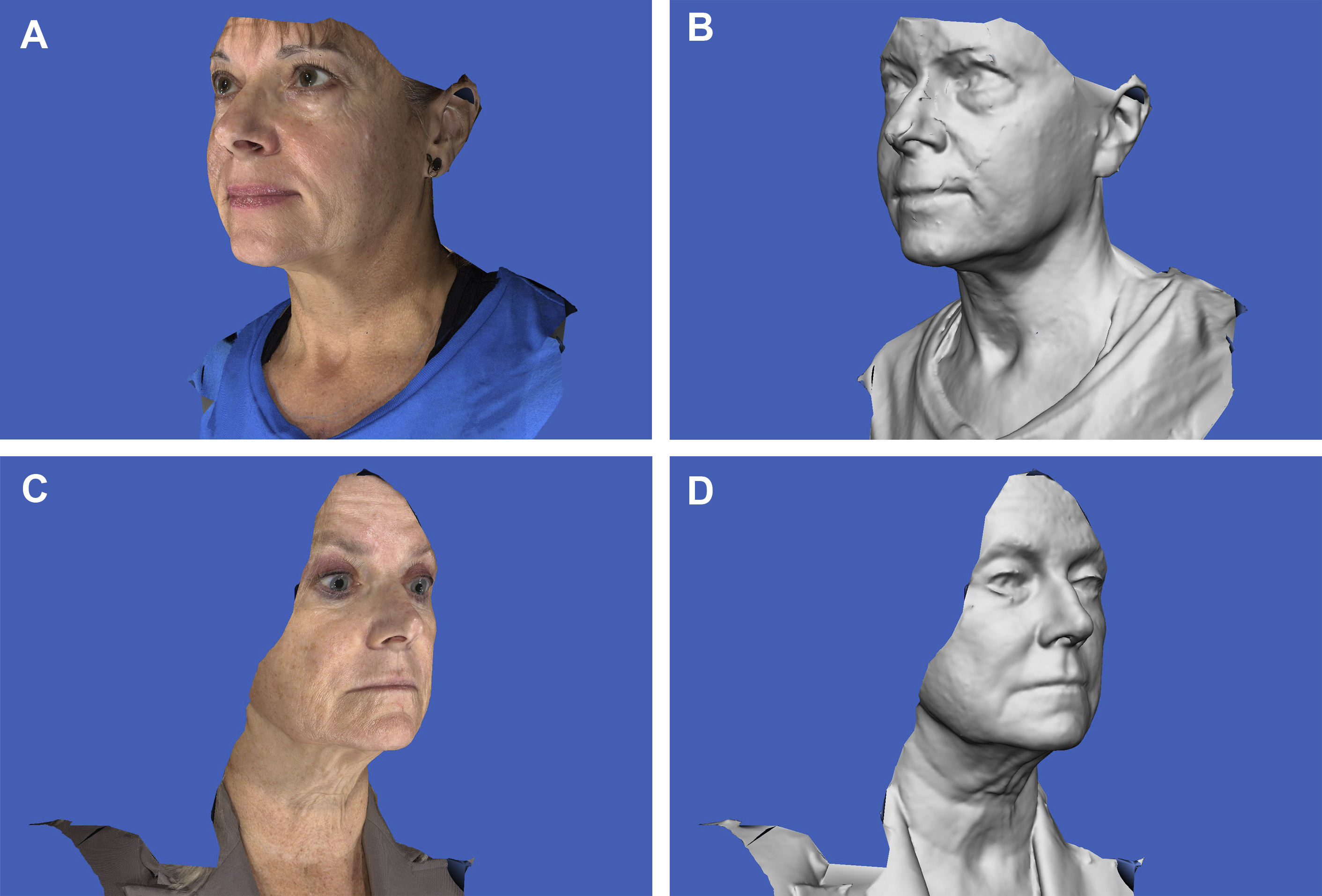

Thorough preoperative evaluation will identify the best surgical candidates for blepharoplasty, as well as steer the surgeon and patient away from unwanted potential postoperative pitfalls. This evaluation is inclusive of patients’ medical comorbidities, as well as their psychological well-being and emotional disposition. It is important to have a frank discussion with patients and record consultations with photographic documentation. This process is aimed toward setting realistic expectations, as well as pointing out any preexisting asymmetries for both patients and physicians to acknowledge. Smoking is discontinued for at least 2 weeks before surgery. All anticoagulants or herbal medications that interfere with blood clotting are discontinued 2 weeks before surgery. Thyroid disorders are investigated and noted, as hypothyroid and hyperthyroid states cause disparate influences on the periorbital area that cannot be addressed with routine blepharoplasty. Any history of dry eye is investigated with comprehensive ophthalmologic assessment, including the Schirmer test, visual acuity, extraocular movements, intraocular pressure, and cornea and ocular adnexa evaluation. Even with normal Schirmer testing, ophthalmologic and systemic evaluation is indicated to rule-out collagen vascular or other autoimmune disease and provide treatment and an assessment of safety preoperatively.

Physical examination warrants special observation of all dermatologic and structural changes in the periorbital area. Volume changes in the orbit are evaluated, specifically the amount of orbital fat available to transpose. Insufficient volume in the orbital fat requires the use of autologous fat as an adjunct ( Fig. 5 ). Volume excess in the pseudoherniation of the orbital fat accentuates the relative volume deficiency in the nasojugal groove and infraorbital hollows immediately inferior to the orbital fat pseudoherniation. In cases in which the lower eyelids have less dermatochalasis and orbicularis muscle redundancy, the transconjunctival approach is a more appropriate choice, leaving the orbicularis muscle untouched. Mild skin redundancy can then be treated with a skin pinch procedure or resurfacing with a peel or laser.

Excessive lower eyelid laxity should be assessed, defined as a snap test >1 second and distraction test (being able to distract the lower eyelid from the globe) >10 mm. On close inspection of those patients with excessive skin laxity, preoperative scleral show is often seen ( Fig. 6 ).

Indications for transcutaneous lower blepharoplasty include excess skin and orbicularis muscle that requires redraping for adequate lid recontouring and lower eyelid rejuvenation. This approach also allows for broad exposure, for wide release of the orbitomalar retaining ligaments, and orbital fat transposition.

Today I have 3 absolute contraindications for using the transcutaneous approach. In the past, excessive laxity of the eyelid was a relative contraindication to transcutaneous lower blepharoplasty, but in my practice today it is an absolute contraindication. The transcutaneous approach in cases with increased laxity can lead to postoperative eyelid malposition on a spectrum from lateral canthal rounding to frank ectropion even when additional adjunctive procedures were included to prevent problems. In these cases, I would include a concomitant canthopexy, or horizontal lower eyelid tightening procedure (such as a lateral tarsal strip procedure), depending on the degree of laxity, and I would still wind up with malposition in 10% to 20% of cases. In cases of more extreme laxity with a lower eyelid tightening procedure, the eyes would appear smaller, distressing the patient. This problem was not reversible ( Fig. 7 ). To avoid all this, I now use a transconjunctival approach and treat the skin and muscle less aggressively in cases with more significant eyelid laxity.

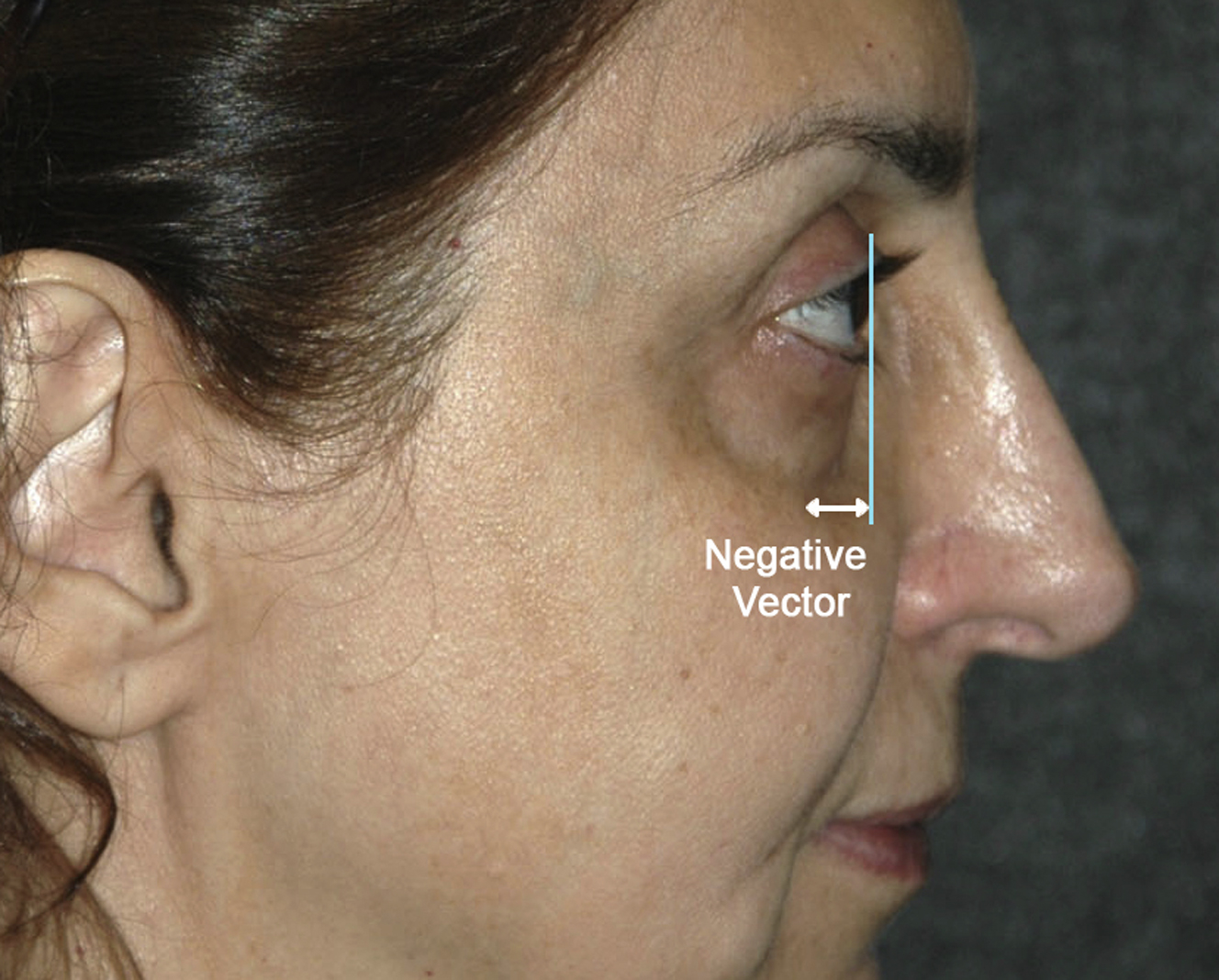

The other 2 absolute contraindications for transcutaneous blepharoplasty include patients with a negative vector and preoperative orbicularis weakness. A negative vector eyelid is noted when the patient’s profile is examined (sagittal view) the cornea projects more anteriorly than the midface ( Fig. 8 ). In these cases, I use a transconjunctival approach. These 2 preoperative physical findings have been noted in a study by Griffin and colleagues on post-blepharoplasty lower eyelid retraction patients to be present in 65% and 85%, respectively. When tightening the eyelid skin and orbicularis muscle, the tendency is for the redraped tissue to fall under the globe in a negative vector eyelid, similar to the way pants fall underneath a “beer gut.” Patients with preoperative orbicularis weakness are also predisposed to lower eyelid retraction, and skin muscle flap surgery further weakens the muscle with denervation, loss of strength, and lower eyelid margin eversion. Orbicularis strength is assessed by trying to pry the patient’s eyelids open during forceful closure by the patient. In a normal situation, the examiner cannot open the patient’s eyelids. With more degenerative changes and age, the eyes are easily pried apart. In both of these situations, we elect to approach the orbitomalar ligament and orbital fat transconjunctivally and address the skin externally by pinch technique and suspending the orbicularis muscle redundancy with suture fixation to the orbital rim and/or plicating the lateral orbicularis muscle.

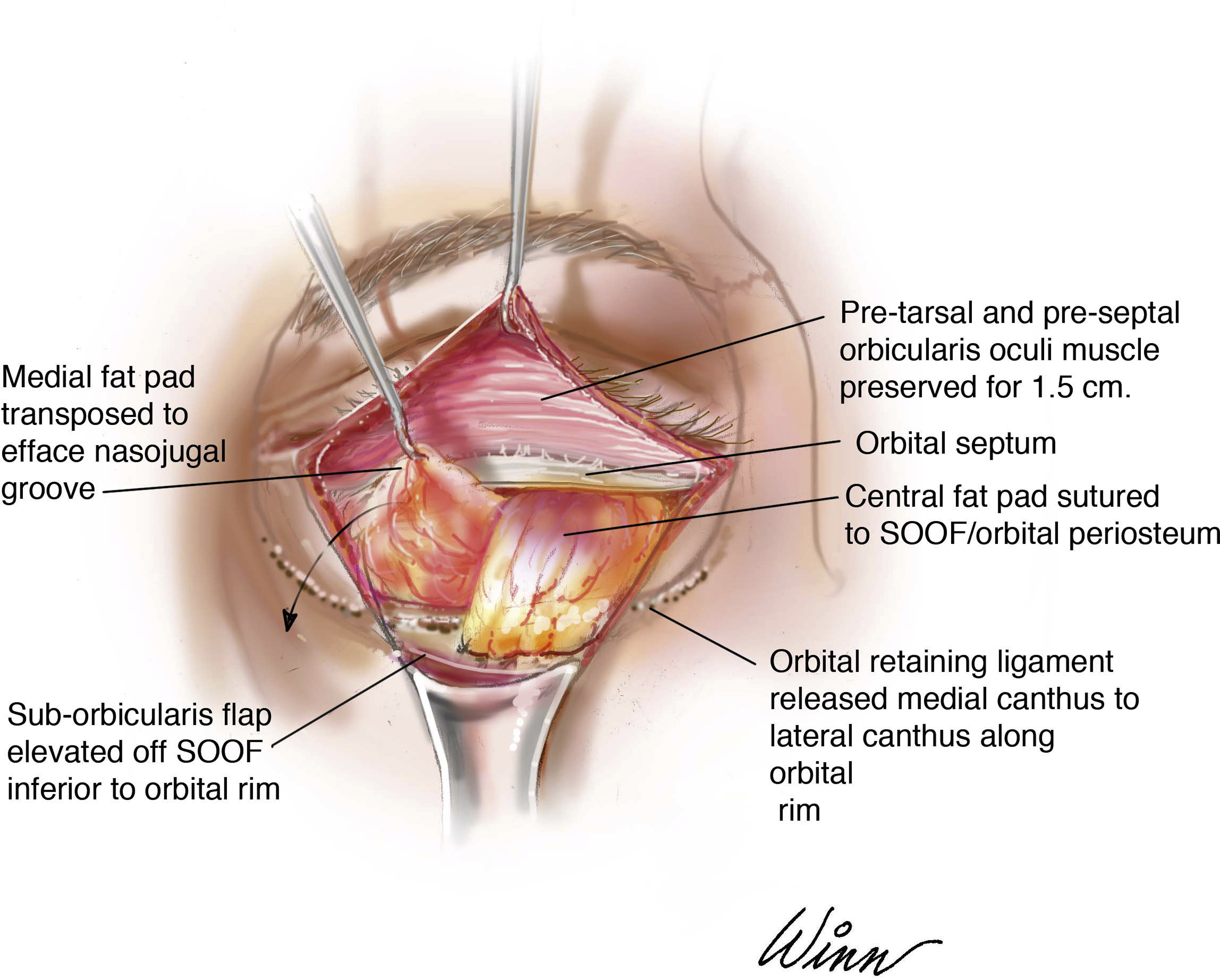

Transcutaneous blepharoplasty surgical procedure

Our transcutaneous lower blepharoplasty technique is an extended transcutaneous submuscular blepharoplasty with orbital-malar ligament release and orbital fat repositioning ( Fig. 9 ). Depending on the patient’s preoperative degree of infraorbital volume loss, this approach is used including the infraorbital ligament release with fat removal, partial removal and transposition, or complete transposition. Using this method of periorbital volume replenishment is predicated on the presence of sufficient orbital fat volume for transposition. I prefer orbital fat transposition when orbital fat is available because it is a vascularized pedicled fat flap that has an essentially 100% take, whereas injected autologous fat is a free graft and fails to incorporate in as high as 35% of patients in our experience. To minimize the risk of lower eyelid malposition, our approach preserving a robust orbicularis oculi sling, and incorporates periosteal fixation of the lateral canthus and skin muscle flap. What follows is my description of the techniques in 6 steps.