CHAPTER 78 Total facial alloplastic augmentation

Historical background

The senior author (E.O.T.) is widely recognized for his unique and bold contribution to the development of reproducible and more anatomically precise alloplastic implants for facial rejuvenation (Terino, 1992). This was a time period when the surgical community was still greatly influenced and biased toward the sole use of autologous craniofacial reconstruction techniques pioneered by the Paul Tessier (Tessier, 1971).

In the 20th century, chin alloplastic augmentation was first described in 1948 (Rubin and Walden, 1955). Gonzalez-Ulloa is credited to be among the first surgeons to describe malar augmentation with alloplastic implants (Gonzales-Ulloa, 1957). In the mid-1960s, Ulrich Hinderer developed unilateral corrective malar silicone implants (Hinderer, 1975).

The evaluation

Patient evaluation for total alloplastic facial augmentation includes the following:

• What problem does the patient want you to solve?

• Get the patient’s verbal description of his/her “ideal scene” appearance of facial change.

• Patient “homework assignment”: bring magazine photos of specific “do’s and don’ts” on desired anatomic part changes.

• Have older patients bring a variety of earlier personal photos.

• Use computer face photos (five views) and imaging technology to do the consultations.

• Use an anatomic facial zone model and facial type analysis.

• Use a personality profile test of the surgeon’s choosing to objectably predict patient satisfaction, an extremely important consideration after downplayed or ignored to the risk of the surgeon.

Applied anatomy for total alloplastic facial augmentation

Interrelationships of the facial promontories

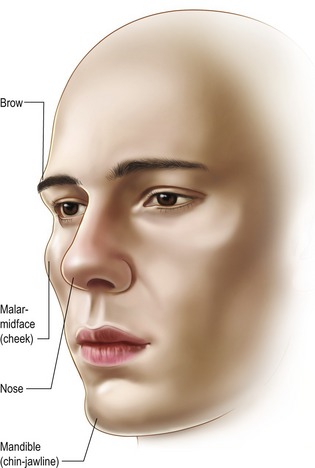

These are three major promontories of volume and mass. In order of importance, they are the nose, the two malar zygomatic eminences, and the chin–jaw line (Fig. 78.1). The supraorbital ridges, constitute a fourth promontory, which are of lesser significance (and will not be discussed in this chapter).

By altering the interrelationships of the three major prominentories, a surgeon can uniquely create or restore facial harmony, balance, and beauty. By mathematical law, the diminution or enhancement of any one of the three promontories directly and inversely affects the aesthetic importance of the others. Facial aesthetics is the art and science of achieving beauty by creating a balance in all three elements of facial skeletal anatomy. One important method by which the aesthetic surgeon can accomplish this balance is by properly employing alloplastic implants (Fig. 78.2). Recent advances in applied alloplastic implant technology now make it possible for the surgeon to make subtle or dramatic changes in the facial promontories with ease and predictability.

The restructuring of all these layers still has many limitations. Patients who display round, full, fleshy facial contours with an abundance of subcutaneous fat rarely appear beautiful by contemporary standards. Conversely, there are lean-faced individuals with a tendency to a longer facial contour with inadequate skeletal promontories in the malar or mandibular regions or both. Both extremes of these facial types, as well as innumerable patients who have combinations of volume deficiencies in varying anatomic locations can be significantly improved by rearranging the balance of their skeletal promontories with targeted alloplastic augmentation techniques. Furthermore, contour surgery of the facial skeleton should also be complemented by a wide variety of other sound coordinated facial procedures (Fig. 78.3).

Zonal anatomy of the malar and premandible regions

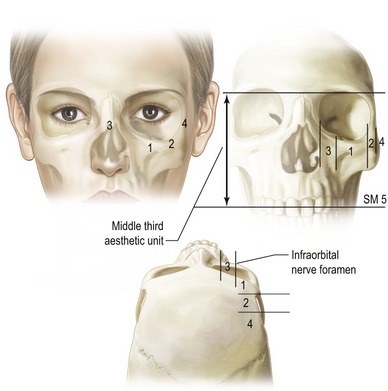

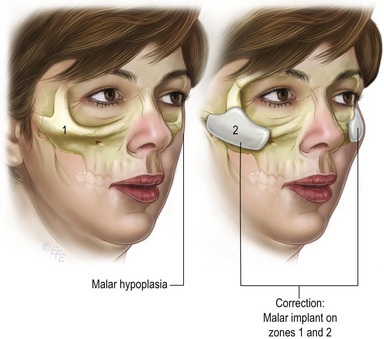

That part of the facial skeleton which, when appropriately augmented, produces an aesthetic change in the contour of midface can be called the “malar-midface space”. To determine the most aesthetic augmentation to select for that space, it is useful to partition the midface region into five distinct anatomic zones (Terino, 1992) (Fig. 78.4). By understanding these five zones and their interrelationships, the surgeon can vary cheek and/or midface shapes to accommodate each unique patient.

Summary of zones

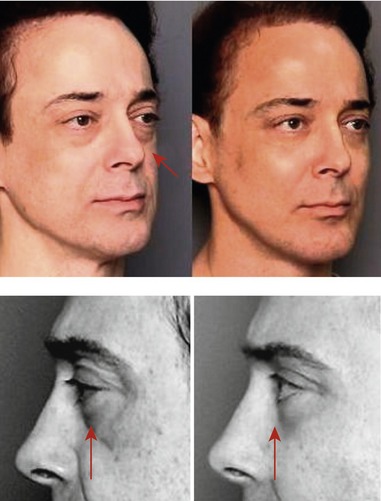

Zone 1, the largest area, includes the major portion of the malar bone and the first third of the zygomatic arch. Augmentation of this entire zone produces the greatest volumetric filling of the cheek and also maximizes the projection of the maxillary eminence (Fig. 78.5).

Zone 2, the second most important site, overlies the middle third of the zygomatic arch. Enhancement of this zone along with zone 1 increases accentuation of the cheek bone laterally, giving a broader dimension to the upper third of the face, and creating a high, arched appearance. This change of contour is particularly useful for individuals with a narrow upper face or a long-face syndrome. When, however, zones 1 and 2 are augmented in excess, an abnormal and unattractive protuberance may result (Fig. 78.6).

Zone 3 is the paranasal area, which lies medial to the infraorbital foramen and nerve. A line drawn vertically down from the infraorbital foramen marks the medial extent of the usual dissection for malar augmentation. This line also represents the lateral border of zone 3. When paranasal augmentation in zone 3 occurs, medial fullness of the face is created, often in the upper nasolabial area, which can be unattractive or can produce a “chipmunk-cheek” effect. The skin and subcutaneous tissues are thin in that region; consequently, any implant placed there must be carefully sculptured and tapered. Augmentation of zone 3 is indicated for certain reconstructive purposes, following trauma or other heredity deficiencies (Fig. 78.7).

Zone 4 overlies the posterior third of the zygomatic arch. Augmentation in this area is never needed as it would produce an unnatural appearance. Moreover, dissection here may be dangerous, since it is very possible to injure the zygomaticotemporal or orbicularis oculi branches of the facial nerve, and even the capsule of the temporomandibular joint. Infrequently, deformities have been observed that resulted from operations in this area.

Zone 5, the submalar zone or “submalar triangle,” is bounded posteriorly by the tendonous surface of the masseter muscle, and anteriorly by the canine fossa region of the maxilla. The superior boundary of zone 5 is the inferior margin of the malar bone, which constitutes the first two thirds of the zygomatic arch. The medial extent of the submalar space ends at the lateral border of the nasolabial mound and sulcus. Its anterior limit is bounded by the inferomedial portion of the roof of the entire malar-midface space. It contains the overlying facial musculature, fat, skin, and subcutaneous of the midface region. The inferior limit is selected by the surgeon in the natural dissection plane that separates the masseter from the overlying facial musculature according to the desired configuration of midface fullness selected by the patient. This equates to creating certain breast shape by choosing the lower limit of the submammary sulcus.

Fig. 78.5 Malar hypoplasia and the resulting malar-midface contour from Zone 1, 2 malar volume enhancement.

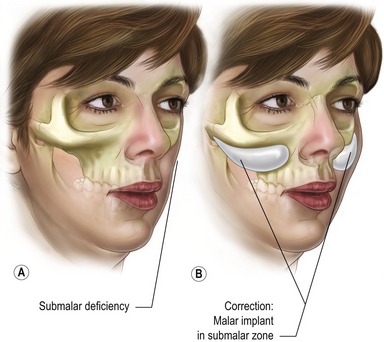

A type 2 facial aesthetic deficiency consists of a soft tissue contour depression specifically in the lower aspect of the midfacial aesthetic unit called the submalar zone 5 (SM5) or submalar “triangle”. This deficiency resides over the masseter tendon and the canine fossa lying under the inferior border of the malar bone and zygomatic arch. A large malar shell implanted over the inferior aspect of the malar bone in zone 1 and extending into the submalar space below the border of the malar bone creates the illusion of a round, full “apple cheek” in females.

By definition, a comprehensive augmentation of the entire malar-midface unit may require an implant shell with maximal transverse dimensions of 5.5 cm across and 4.5 cm vertically. A type 2 face has adequate malar bone prominence, but is deficient in submalar soft tissue volume. This creates a flat, older, midface contour. This frequently occurs in the aging face of both males and females. In a young individual with strongly defined cheekbones and yet deficiencies in the midface soft tissues, a submalar augmentation produces aesthetic softness, and adds youthful fullness to the face. Some people feel strongly that a submalar implant can lift the nasolabial sulcus and give the illusion of facial tightening that will postpone the perceived need for rhytidectomy. The authors have not observed this occurrence. The authors favor volume filling of the midface just posterior to the nasolabial mound, in order to de-emphasize the appearance of fullness and simultaneously correct the soft tissue volume deficiency in the midface.

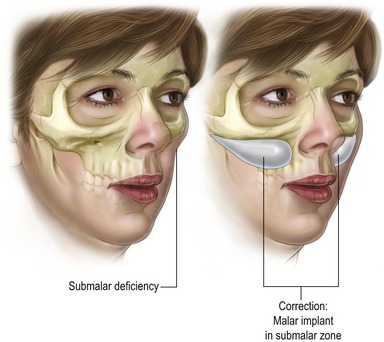

A type 3 facial aesthetic deficiency in a face consists of a very strong malar zygomatic superstructure and a very sunken submalar infrastructure. Such faces often have thin skin and subcutaneous support requiring a generous submalar augmentation with a projecting implant thickness (5–8 mm). This facial type occurs with aging, as well as from heredity (Fig. 78.8). The appearance is that of an emaciated, drawn, haggard and even sick countenance. This can result from soft tissue disease states such as Romberg’s hemi-atrophy and HIV lipodystrophy. The remedy, for any etiology, is the same: a generous volume filling of the submalar zone 5 (SM5) (Fig. 78.9).

Type 5 aesthetic facial deficiency exists as a weakness of facial structure in the suborbital “tear trough” region. This creates a tired and “hollow” appearance around the eyes, especially in the lower orbital region. There may also be a tendency for the eyeball itself to look proptotic due to the “negative vector” orbit (Fig. 78.10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree