14 Thumb and finger reconstruction

Microsurgical techniques

Synopsis

Microsurgical toe-to-hand transplantation has allowed the possibility of replacing “like for like” tissues, achieving good functional and aesthetic results with acceptable donor site morbidity.

Microsurgical toe-to-hand transplantation has allowed the possibility of replacing “like for like” tissues, achieving good functional and aesthetic results with acceptable donor site morbidity.

Early consideration of toe-to-hand procedures at the initial debridement ensures careful preservation of all viable neurovascular bundles, flexor and extensor tendons, mobile joints, and skin in order to maintain or achieve maximal functional results with minimal dissection of the foot.

Early consideration of toe-to-hand procedures at the initial debridement ensures careful preservation of all viable neurovascular bundles, flexor and extensor tendons, mobile joints, and skin in order to maintain or achieve maximal functional results with minimal dissection of the foot.

Retrograde dissection of the vascular pedicle facilitates toe harvest and alleviates concerns regarding any variations in the vascular anatomy of the donor vessels.

Retrograde dissection of the vascular pedicle facilitates toe harvest and alleviates concerns regarding any variations in the vascular anatomy of the donor vessels.

Amputated thumbs can be successfully reconstructed with various modifications of the great toe, including whole great toe, trimmed great toe, great-toe wrap-around flaps, and the second toe.

Amputated thumbs can be successfully reconstructed with various modifications of the great toe, including whole great toe, trimmed great toe, great-toe wrap-around flaps, and the second toe.

Amputated fingers can also be successfully reconstructed with various configurations from lesser toes, achieving results comparable to that of the thumb.

Amputated fingers can also be successfully reconstructed with various configurations from lesser toes, achieving results comparable to that of the thumb.

The “metacarpal hand” refers to a hand with amputations of all fingers proximal to a critical functional level with or without accompanying thumb amputations. Toe-to-hand transplantations can help restore maximal hand function to this once permanently crippling condition, even for bilateral defects.

The “metacarpal hand” refers to a hand with amputations of all fingers proximal to a critical functional level with or without accompanying thumb amputations. Toe-to-hand transplantations can help restore maximal hand function to this once permanently crippling condition, even for bilateral defects.

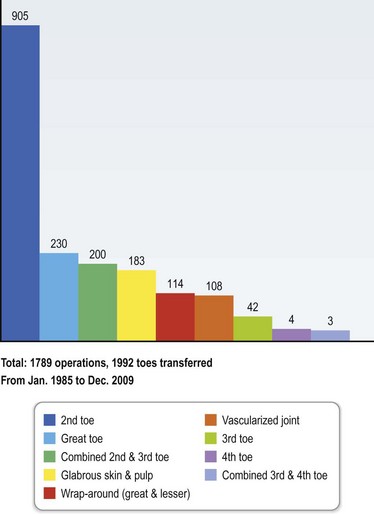

Our large series of over 1700 cases allows continual pioneering of new concepts, refinements of existing techniques, improved classification systems, and strategic management algorithms that will enable easier mastery of toe-to-hand transplantations.

Our large series of over 1700 cases allows continual pioneering of new concepts, refinements of existing techniques, improved classification systems, and strategic management algorithms that will enable easier mastery of toe-to-hand transplantations.

Introduction

The first toe-to-thumb procedures were performed by Yang1,2 in 1966 and Cobbett3 in 1967. These were among the first free tissue transfers to be attempted and probably reflects the central role of the hand, and the obvious logic in using toes to replace missing digits. The human hand functions through a combination of different prehension patterns, adequate motor strength, and sensory feedback. Such a unique combination requires the presence of mobile joints, specialized glabrous skin composition with a rich sensory input especially in the fingertips, with accompanying splintage from healthy nails. Following digital amputations, the replacement of “like for like” tissues that restores these exacting demands is only achievable by a successful replantation.4–6 In cases of failed replantations, toe-to-hand transplantations remain the next best option with a superior result than the use of prosthesis or other nonmicrosurgical techniques to achieve functioning digits with acceptable sensibility and appearance.7–13

To date, toe transplantation for thumbs has been established as the gold standard in replacing mutilated or unreplantable thumbs.14–17 The use of toes to replace missing fingers, however, has been somewhat less acknowledged and controversial, partly due to the perceived insignificance of finger loss and overall discomfort with the technical challenge involved, resulting in a general reluctance to carry out a “big operation” for a “small injury.” In certain select patient groups, however, especially those with demanding functional18 or aesthetic concerns,19 replacing single fingers with composite tissues offers satisfactory results, even when carried out solely for cosmetic and psychological reasons.20–22 In certain occupations, e.g., musicians, these operations provide the only hope of continual meaningful employment. When multiple fingers are amputated, the resultant disability is comparable to the loss of the thumb and drastically alters the appearance of the hand.8,23–26 The “metacarpal hand” is a devastating injury with amputations of all fingers proximal to a functional level with or without accompanying thumb amputations.12,27,28 Toe-to-hand transplantations remain the only useful option for this condition to restore functional usefulness, especially in bilateral defects.29,30

The growing literature, especially in the area of toe-to-hand transplantations for finger amputations, reflects the increasing acceptance among surgeons for this procedure and also a relentless pursuit to achieve excellence in outcomes31–38 and improved donor site morbidity39–41 through continuous innovation. The reconstructive surgeon wishing to replace missing thumbs or fingers with toes now has a wide range of options for selection in order to achieve optimum results. This chapter outlines the current experience of toe-to-hand transplantations, drawing from our experience of more than 1700 cases over a 30-year period at Chang Gung University Medical College Hospital (Fig. 14.1).

Historical perspective

Before the introduction of microsurgery, Carl Nicocolandi42 in 1897 was the first to recognise the suitability of replacing lost digits with toes by reporting the first pedicled toe-to-thumb reconstruction in a 5-year-old child. It is interesting to note that he arrived at this logical conclusion following initial dissatisfaction with the use of tubed chest flaps due to their bulkiness. Davis43 subsequently improved on this technique of pedochyrodactyloplasty with his review of 40 cases and represented probably one of the earliest examples of innovation in toe-to-hand transplantations. It was not until 1966 that the first microvascular toe-to-hand transplantation was to be attempted in a rhesus monkey by Buncke and Schulz.44 Following closely in 1967, Yang and Gu2 became the first pioneers to use the second toe for thumb reconstructions in humans, with Cobbett3 reporting the use of the great toe 2 years later in 1969. A recent follow-up of his patient at 30 years shows good subjective sensation and no evidence of osteoarthritis.45

Following these proven results in adult traumatic injuries, a logical progression would be to extend these experiences to congenital anomalies. O’Brien et al. were the first to report the use of toe transplantations for congenital absence of the thumb.46 This technique was further popularized later by Gilbert47 and Cooney and Wood,48 who extended the indications to the replacement of fingers as well as thumbs. Four decades have passed since the pioneering microsurgical operations of Buncke and others, both experimentally and clinically. Since their initial efforts, the numerous successful series as well as reports of new innovations continually demonstrate the safety, reliability, and preference of toe-to-hand transplantations for traumatic hand injuries, as well as the special place it occupied and will always occupy in the history of reconstructive microsurgery.

Diagnosis/patient presentation

The initial management of the potential toe-to-hand transplantation patient is similar to any other trauma or patient requiring digital replantation, with resuscitation and management of concomitant life-threatening injuries if necessary, and appropriate preservation of the amputated digits. Initial assessment of the injured hand allows pre-emptive discussion of toe-to-hand transplantation with the patient, especially when the possibility of a successful replantation is in doubt, such as in severely avulsed, crushed, or multiple amputations. In particular, patients whose occupation requires a high-demand use of their hands or those with special needs and hobbies requiring a fine degree of dexterity and 10 fingers, e.g., musicians or athletes, should be given all information available concerning different reconstructive options. If there is significant soft-tissue damage, or anticipated soft-tissue lack following debridement, additional cover with the use of pedicled groin flaps should be considered at the time of the initial operation and discussed with the patient (Fig. 14.2).

The initial operation

Anticipation of either primary or secondary toe-to-hand operations ensures careful preservation of all viable structures at the initial debridement or following failed replantation.49,50 Excessive shortening of structures in order to achieve direct wound closure or the use of local flaps should be avoided10 with the use of a pedicled groin flap instead; with the following advantages: (1) donor site on the foot can be primarily closed without the need to harvest large amount of skin with the toes; (2) skin grafts in the hand can be avoided, thus improving the appearance of the toe transplantation; and (3) an adequate webspace can be created with the excess skin available. Although some reports have suggested other methods of additional soft-tissue harvest with the toe transplantation, either as a single-stage microvascular procedure with combined free flaps,51 or the use of native foot tissue,31,52 we recommend a groin flap for the majority of cases as it is quick and simple to perform and leaves an almost negligible donor scar.

As the use of intraosseous wires is an effective method of osteosynthesis53 and only requires 0.5 cm of bone for wire placement, as much remnant bone should be preserved as possible. In transjoint amputations, any intact articular cartilage and accompanying ligaments should be preserved to facilitate joint reconstruction with disarticulated toe joints.54 Amputations at the level of the thumb metacarpals can be augmented with the use of bone blocks, thus avoiding the need for a transmetatarsal osteotomy in great-toe harvest, as preservation of the metatarsophalangeal joint is important for foot function and appearance.12,55

Avulsed or shredded extensor and flexor tendons should be debrided but never sacrificed for the sole purpose of obtaining wound closure. In fingers, preserving the native intrinsic extensor apparatus as far as possible, especially over the proximal interphalangeal joint, allows preservation of the arrangement of the intrinsic and extrinsic extensor systems56 following reconstruction. Similarly, preserving the insertion of the flexor digitorum superficialis, wherever possible, has proved useful in achieving better functional results.50,57

Excessive shortening and the use of cauterization of arterial and venous ends are to be avoided in order to minimize intimal damage and preserve length, avoiding more extensive foot dissection and the need for vein grafts which prolong the operation and increase complications.58 The same applies to nerves. Traditional teaching of the “pull and cut” method for prevention of neuromas in amputated stumps is to be avoided, as sensory recovery is much faster when nerve length is preserved and neurrorhaphy performed nearer to the transferred toe.59 All neurovascular bundles should be tagged carefully with 10/0 sutures to ensure easier identification at the subsequent reconstruction.

Patient selection

Patient factors

Careful patient selection is the key to success. Age is not a contraindication, although the demands of hand function decrease with advanced age. Furthermore, the higher risks of thrombosis60 as well as lessened sensory recovery61 have to be carefully discussed with the elderly patient. Ideal patients are well motivated and clear about their needs and goals with good overall health. Decision-making for each patient is individualized not simply for the injury status but also to take into account the hand dominance and occupation as well as socioeconomic status.

Primary versus secondary reconstruction

Although secondary toe-to-hand procedures may appear to be the logical choice to ensure better wound control and definition of the zone of injury, a primary reconstruction (before the wounds are closed or have healed) allows a one-stage procedure, earlier rehabilitation, and subsequent return to work, as advocated by several authors.20,62–64 In our study of 26 primary cases versus 96 secondary cases, there was no significant difference in terms of vascular re-exploration rates, recipient site complications, or requirement for secondary revision.64 In a well-informed and motivated patient without extensive soft-tissue loss or other significant injuries of the ipsilateral upper limb, primary toe-to-hand transplantation offers the ideal method of replacing digit loss. On the other hand, the procedure is best delayed in patients who are unsure about their decisions and who also communicate their reluctance to undergo further rehabilitation.

Injury factors

Decision-making for the thumb

The functional thumb depends on adequate length, sensibility, mobility, and stability. Microvascular toe-to-thumb transplantations allow these four objectives to be achieved in a single stage with a superior aesthetic result. The function of the thumb decreases by 50% once the amputation level is proximal to the proximal interphalangeal joint and reaches 100% once it crosses the metacarpophalangeal joint.65 Amputations distal to the interphalangeal joint are generally well tolerated but, in certain patients, the additional length, stability, and sensibility from a transplanted distal toe transfer should always be offered as an option.59,66

Various classifications and reconstructive algorithms exist for thumb defects,67–69 although the underlying principles relate mainly to the types of tissue and the length of thumb missing.70 Toe-to-thumb transplantations can be successfully reconstructed with various modifications of the great toe, including whole great toe,66 trimmed great toe,71 great-toe wrap-around flaps,72 pulp flaps,73 and the second toe.29,52 The decision to use which toe or its variation should be individualised not only to the thumb defect and the patient’s needs, but also with careful consideration to the donor site. In general, thumb reconstruction using the great toe or its variants provides a better functional and aesthetic outcome than use of the lesser toes, although augmentation procedures for second toes to improve bulk have been described.52 If the great toe is used, at least 1 cm of the proximal phalanx should be preserved in the foot to ensure better push-off and preservation of foot appearance; the great toe is therefore an ideal option for thumb amputation levels distal to the mid-metacarpal shaft. In more proximal amputations, a transmetatarsal transfer of the second toe or additional methods like preliminary distraction lengthening of the existing metacarpal or interpositional bone grafting between the transferred toe and the metacarpal without sacrificing the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe are preferred.12,30,59

Decision-making for fingers

Classification of finger defects is similar to the thumb and pertains to the type of tissue and length of finger missing, with the additional consideration of which finger is involved and whether there is single or multiple amputations. The definition of proximal or distal amputations is determined by its relation to the insertion of the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon.49,59,74 Toe transplantation to more distal finger amputations can be achieved by a wide variety of options, including the use of vascularized nail grafts,75–77 pulp flaps,78 wrap-around flaps,33 and partial second toe,19 depending on what tissues are missing. These operations are rewarding due to the restoration of high-density pulp sensation, fine pinch, and cosmetic appeal of the nail.74,75,79 A partial second-toe flap includes either only the distal interphalangeal joint or both the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints, and is indicated in amputations distal to the flexor digitorum superficialis insertion.18,74,80,81 In contrast, a whole second-toe flap is indicated in carefully selected patients with more proximal amputations59; the ideal level, however, is distal to the middle of the proximal phalanx as reconstructions for more proximal amputations usually result in a slightly shorter finger.82

Decision-making for patients with multiple finger amputations are largely guided by the specific occupational and cosmetic needs of the patient. In general, two adjacent fingers should be reconstructed wherever possible to allow a stable tripod pinch or hook grip.12,26,81 Preferential reconstruction of the radial two fingers should be recommended for patients who require fine pinch and the ulnar two digits for manual workers who require a strong grip.24,83

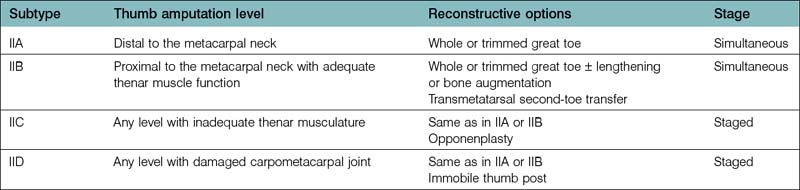

Decision-making for the metacarpal hand

The term “metacarpal hand” refers to a hand injury with multiple finger amputations at the level of the metacarpophalangeal joint, or immediately proximal or distal to it. Delitala was perhaps the first to coin this term84 and, since then, various classification systems have been proposed,85–88 with varying levels of clinical usefulness. A classification system based on reconstructive options and different stages of injury has proved useful in our experience12,55,84 (Tables 14.1 and 14.2). This takes into account the level of finger amputations and relative involvement of the thumb, and provides guidelines for the reconstructive technique as well as prediction of the functional outcome after reconstruction. Further subclassified into two types for these purposes, type I refers to an injury with four-finger proximal amputations without thumb or only distal-thumb involvement (no thumb reconstruction necessary). In type IA injuries, where the amputation level is distal to the metacarpophalangeal joint, the focus is on the selection of two separate toes or combined second and third, or third and fourth toe transplantations (Fig. 14.3). To ensure that the different digits curve around an object more evenly in grasp prehension, the length of the remaining amputation stumps should not be longer than that of a normal little finger when considering a combined second- and third-toe transfer.83 For type IB injuries, where the amputation level is through the joints with intact articular surfaces, combined second and third toes are harvested as composite joint transfers. More proximal injuries (IC) where the amputation level is proximal to the metacarpophalangeal joints require the harvest of combined second and third toes as transmetatarsal transfers. Reconstruction of two adjacent fingers allows for a stable tripod pinch, although reconstruction of all four fingers is possible in certain selected patients (Fig. 14.4).12

Table 14.1 Metacarpal hand classification for type I defects

| Subtype | Thumb amputation levels | Finger amputation levels |

|---|---|---|

| IA | Amputation distal to the interphalangeal joint | Distal to the level of metacarpophalangeal joint |

| IB | At the level of the metacarpophalangeal joint | |

| IC | Proximal to the level of the metacarpophalangeal joint |

Type II injuries refer similarly to four-finger proximal amputations but with various levels of thumb involvement. The reconstruction of fingers with toe transplantations follows a similar decision-making process as for type I defects, but reconstruction of the thumb is determined by the presence or absence of a functional thenar musculature. If the thenar muscle is intact or possesses adequate function (types IIa and IIb), a one-stage procedure to reconstruct the thumb and two adjacent fingers is recommended. If the thenar muscle presents with missing or inadequate function (IIC), the thumb reconstruction should be delayed until after the finger reconstructions and the thumb position first determined by the aid of a prosthetic thumb while the fingers assume its final positions (Fig. 14.5). This is to allow proper length and positioning of the reconstructed thumb in a suitably adducted and opposed posture at the second stage to facilitate an effective tripod pinch prehension. Tendon transfers for opposition transfers can also be carried out at the time of the second stage, if necessary.89

Decision-making in bilateral metacarpal hand injuries requires a careful balance of the severity of injury (type I or II), the patient’s needs, and acceptable level of donor morbidity. Type II injuries are much more difficult than type I, requiring up to but not exceeding five donor toes to achieve a functional level of prehension.30 In general, the use of a great toe, usually from the left or nondominant foot, is sacrificed for dominant thumb reconstruction together with a combined two-toe reconstruction from the opposite foot to achieve a tripod pinch. In the nondominant hand, single-digit pulp-to-pulp pinch is considered adequate with the use of a lesser toe for thumb reconstruction.30 Although the option of sacrificing both great toes or more lesser toes for hand reconstruction may seem attractive, we have found that the donor morbidity reaches a level that is incompatible with activities of daily living. In instances where multiple toes are needed, the patient needs to participate fully in the decision-making with regard to the foot morbidity, especially in certain populations where patients are far less tolerant of sacrificing their toes to reconstruct their hands (Fig. 14.6).29

Treatment/surgical technique

General principles in vascular dissection

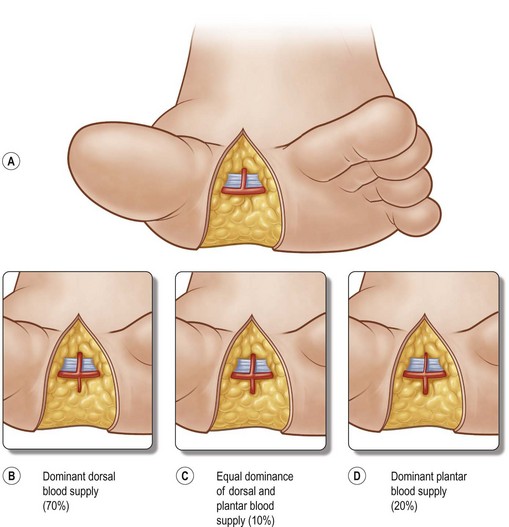

Dissection of the vascular pedicle remains a source of confusion and frustration for surgeons wishing to embark on toe-to-hand transplantations. Adopting a retrograde dissection method of the arterial pedicle alleviates concerns regarding vascular anatomy and greatly facilitates easier dissection.90,91 Begin by dissecting the pedicle in the web space and identifying the dominant blood supply to the toes, having a working knowledge of the three types of arterial supply. The first dorsal metatarsal artery (FDMA) is usually dominant (70%) and identified by its dorsal relation to the intermetatarsal ligament (Fig. 14.7).59,92 Once this is confirmed, it permits early ligation of the plantar system which greatly facilitates further dissection. In the 20% of cases where a first plantar metatarsal arterial (FPMA) system is dominant, as identified by its plantar relations to the transverse metatarsal ligament (Fig. 14.7), the FDMA is then ligated and the plantar dissection continued together with the harvest of the digital nerves. The length of the arterial pedicle harvested should be able to reach the chosen recipient artery. However, in a dominant FPMA system dissection should be limited to the nonweight-bearing zones, with the use of vein grafts if necessary to increase pedicle length. In cases where both the FDMA and FPMA appear equally dominant (10%: Fig. 14.7), the dorsal system is always selected due to its easier harvest and less donor morbidity. Following toe harvests, at least 20 minutes should be allowed for observation of adequate perfusion before detaching the flap. The venous drainage system is usually identified after the arterial system, and follows a lazy “S” incision on the dorsum of the foot. One sizeable vein is usually enough from the plexus of veins located in an intermediate layer and drained by the great saphenous vein; they should not be confused with the superficial dermal veins.

Hints and tips

• To facilitate easier dissection and alleviate concerns regarding vascular anatomy, start in the webspace and then trace the arterial pedicle in a retrograde fashion. In 80% of cases, the first dorsal metatarsal artery can be used as the arterial pedicle

• To improve the profile at the toe–digit junction and prevent a bulbous appearance, create four equal mobile flaps through a cruciate incision, and interpose these with the V-shaped flaps of the transplanted toe

General principles in recipient preparation

A two-team approach greatly reduces the overall operating time, surgeon fatigue, and risks of anesthesia.49 Proper preparation of the recipient site allows a smooth transition from flap harvest to inset without any delays. Preservation of all viable lengths of bone, joints, neurovascular bundles, and tendons should have been performed at the initial operation by a surgeon who has working knowledge of toe-to-hand transplantations.50 A cruciate incision allows the creation of four equal triangular flaps for smooth interdigitation with the V-shaped flap of the transplanted toe and prevents the ugly “cobra” appearance that features prominently at the toe–digit junction (Fig. 14.8). Following preliminary inset, excess fatty tissues are trimmed by skeletonizing the neurovascular bundles of the recipient flaps. All these maneuvers allow the creation of a finger or thumb with a more natural-looking appearance.