1 Managing the cosmetic patient

Understanding the motives, expectations, and desires of a patient seeking cosmetic surgery is at least as important as manual dexterity for achieving consistently satisfactory results.1

Synopsis

Societal interest in plastic surgery is increasing:

Societal interest in plastic surgery is increasing:

Understanding the patients motivations for surgery and their expectations of the outcomes are the keys to achieving satisfied patients postoperatively:

Understanding the patients motivations for surgery and their expectations of the outcomes are the keys to achieving satisfied patients postoperatively:

Postoperative follow up should include detailed written instructions and the surgeon’s contact details:

Postoperative follow up should include detailed written instructions and the surgeon’s contact details:

Societal interest in plastic surgery is increasing:

Societal interest in plastic surgery is increasing:

Societal interest in cosmetic surgery

The concept of beauty

What is beauty? The concept of attractiveness seems to be innate and is similar across cultures and religions. While it can be influenced somewhat by social trends and advertising, research shows that subjective attractiveness is largely biological, overlaid with only a small amount of personal preference. Studies looking at the consistency of physical attractiveness ratings across cultural groups agree that facial attractiveness is species-specific, not race-specific.2,3 Research in the US has shown that the ratings provided by Asians, Hispanics, Caucasians, and African Americans correlate well for facial attractiveness overall, although features such as expression and sexual maturity influenced some cultural groups more than others.3 Also, Caucasians and African Americans differed on their judgment of bodies. Judgments can potentially be influenced by cultural norms, for example, the classical Roman nose is very different in size and shape than the African American nose, so what may be considered a deformity in one person may be attractive on another. There is no simple answer to the question of what constitutes beauty, or even an attractive face.

In order to ascertain what makes an attractive face, some researchers have assessed facial features by judging individual faces, then comparing the results with computer-generated composite faces, averaging the individuals.4,5 This research showed there was a trend towards the composite face being more attractive than the faces individually, producing a claim that “attractive faces are only average.” Others have disputed this claim, saying that a mathematically averaged face is not the same as an average face.6,7 Interestingly, functional magnetic resonance imaging scanning of subjects during judgment on the facial attractiveness of strangers has shown that perceived facial attractiveness increases with eye contact rather than with increased physical attractiveness per se.8,9 These studies have also shown that facial attractiveness is a fundamental condition which a stranger can read rapidly. In fact, it takes only 150 ms and no eye movement to judge a stranger’s attractiveness.

Over 2000 articles on the study of facial attractiveness have been published in the past 30 years. Social and psychological literature from the 1970s and 1980s extensively studied the response to physical attractiveness and showed that physical attractiveness has a statistically significant effect on the person’s self-esteem and well-being.2 This implies that beauty has influence which is more than “just skin deep.”10 Pediatric studies have revealed that parents provide better parenting to attractive children and have higher expectations of success for them. Conversely, children with craniofacial deformities have behavioral and anxiety problems.11 Studies have also shown that attractive women receive more dates and are perceived to have more positive social attributes. Housman suggested that physically attractive people are offered greater opportunities for success and happiness throughout their life.10 Attractive individuals are more likely to be hired, promoted, and earn higher salaries than their less attractive counterparts. As the potential benefits go far beyond improved self-esteem, it is perhaps not surprising that individuals are attending their plastic surgeons with requests for surgical and nonsurgical options in an attempt to increase their perceived attractiveness or correct a deformity.

Increasing societal acceptance of cosmetic surgery

The specialty of plastic surgery is rooted in reconstructive surgery for congenital abnormalities and acquired injuries. Surgery for purely aesthetic reasons was incorporated into the field somewhat later. Research from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS) has shown that societal acceptance of plastic surgery is increasing. The ASAPS Quick Facts consumer attitudes survey of 2010 found that 53% of women and 49% of men approve of cosmetic surgery, while 27% of married Americans and 33% of unmarried Americans would consider cosmetic surgery for themselves in the future.11 If you compare these attitudes with previous results, 20% of Americans are more favorably disposed towards cosmetic surgery now than they were 5 years ago. This increased acceptance may be related to the extensive media coverage which essentially normalizes plastic surgery. This includes celebrities openly discussing their plastic surgical procedures, as well as popular television programs such as Dr 90210 and Extreme Makeover. Unfortunately, the downside of making plastic surgery a form of mainstream entertainment is the misrepresentation of the significance, complexity, downtime, and potential complications of undergoing surgery. These issues increase the chance that the patient will present with unrealistic expectations which must be clearly addressed by the plastic surgeon at preoperative consultations.

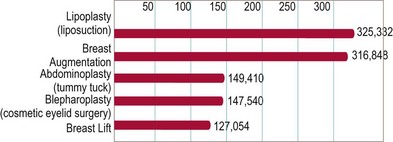

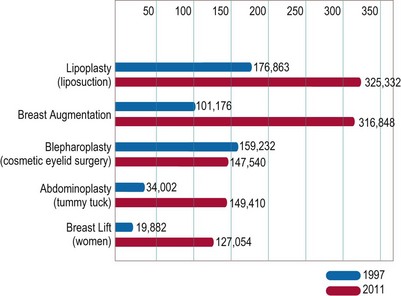

ASAPS statistics for surgical procedures performed by its members in 2011 show that the most commonly performed plastic surgery operations are breast augmentation and liposuction (Fig. 1.1).11 Compared with the surgical statistics from 1997, there has been a significant increase in these procedures (Fig. 1.2). This is in line with the overall 72.5% increase in plastic surgical operations performed over this period. Over this same time period there has also been a significant rise in nonsurgical cosmetic procedures, such as injectables (botulinum toxin, hyaluronic acid, and so forth), laser hair removal, and skin-resurfacing techniques, which have outpaced the growth in surgical procedures, growing 355.6% since 1997. This trend also highlights the public’s acceptance of cosmetic procedures overall, and the popularity of nonsurgical procedures may indicate a pool of potential patients who will consider operative procedures in the future.

Fig. 1.1 Top five surgical procedures in 2011 (American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2011 data.)

Fig. 1.2 Change in procedure numbers 1997–2011 (American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2011 data.)

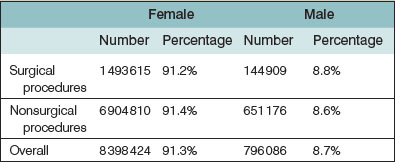

The largest age group of patients undergoing surgical and nonsurgical procedures is between 35 and 50 years of age. Interestingly, statistics show that patients in the younger age group than this (19–34 years) represent a greater proportion of patients who undergo surgical procedures (27.9%) than patients in the older group (51–64 years: 23.3%), while the older group more commonly underwent more nonsurgical procedures than the younger (Table 1.1). This may be related to the increasing societal acceptance of plastic surgery, as younger people tend to be quicker adopters of a new trend than older persons. Not surprisingly, the majority of plastic surgical and nonsurgical patients are female (Table 1.2).

Table 1.1 Age distribution of plastic surgery patients (American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2011 data)

Patient motivation for cosmetic surgery

As Greer stated in 1984, “Understanding the motives, expectations, and desires of a patient seeking cosmetic surgery is at least as important as manual dexterity for achieving consistently satisfactory results.”1 The patient may seek cosmetic surgery for any number of reasons. Elucidating the patient’s motivation is a goal of your first patient encounter. The best reason for wanting plastic surgery is for self-improvement. However, there are many other potential reasons. Patients may feel that surgery will alter their life in some way, perhaps make them more outgoing, help them secure a partner, or save their marriage. The surgeon must be wary of patients with hidden agendas, as an excellent surgical outcome may still not result in a happy patient postoperatively.

Special patient groups

The male cosmetic surgery patient

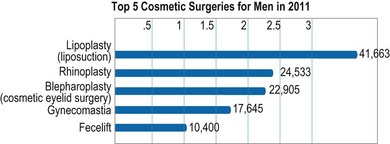

Male patients account for nearly 9% of all cosmetic surgery in the US and men underwent nearly 145 000 cosmetic surgery operations in 2011.11 While the most common operations include lipoplasty and rhinoplasty (Fig. 1.3), men also represented 9% of all facelift (rhytidectomy) procedures in 2011.

Fig. 1.3 Top five cosmetic surgeries for men. (American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2011 data.)

Importantly, men are often overrepresented in the complication data for their procedures, particularly hematoma rates. This should be thoroughly discussed with patients before surgery. The reported incidence of hematoma following male rhytidectomy ranges from 8 to 13% in most series, twice as high as for females. This may be related to the greater vascularity of the male facial skin, with a higher number of microvessels to supply the hair follicles.12 Strict perioperative blood pressure control may be the most important aspect of care to reduce this rate. To this end, we routinely give males clonidine (a centrally acting, alpha2 adrenergic receptor agonist) 0.1 mg postoperatively. This helps stabilize their blood pressure and is long-acting, with a half-life of about 12 hours.

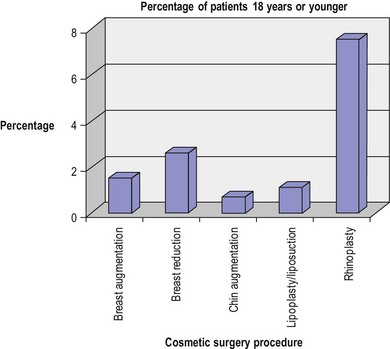

The young cosmetic surgery patient

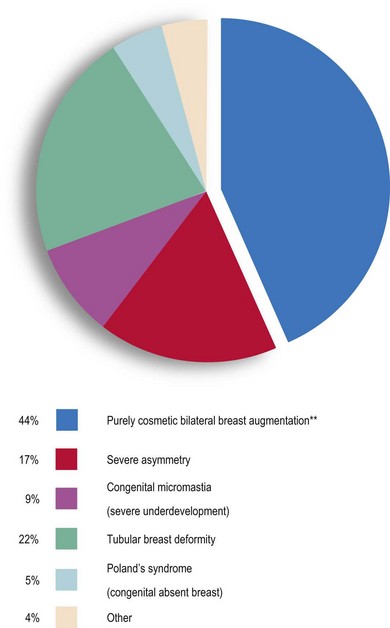

How young is too young for plastic surgery? This is not a straightforward question and the answer usually depends on the reason for the surgery and the degree of patient deformity and concern. The number of teenage patients is small – only 2.1% of all patients undergoing plastic surgery in 2011.11 Data from the last 12 years of reporting from both the ASAPS and the ASPS show similar rates every year over the time period, ranging between 1 and 3%. Excluding otoplasty (cosmetic ear surgery), rhinoplasty is the most common surgery for teenagers overall (Fig. 1.4). While ASAPS 2011 data show that only 1.5% of all breast augmentations were performed on women 18 years of age and under, over 44% of these were performed for purely cosmetic purposes (Fig. 1.5). This is despite the fact that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only approves saline-filled breast implants for cosmetic augmentation in women age 18 years and over, and silicone-filled implants for women 22 years and older. The FDA states that this restriction is placed because “breasts continue to develop through late teens and early 20s and because there is a concern that a young woman may not be mature enough to make an informed decision about the potential risks.”

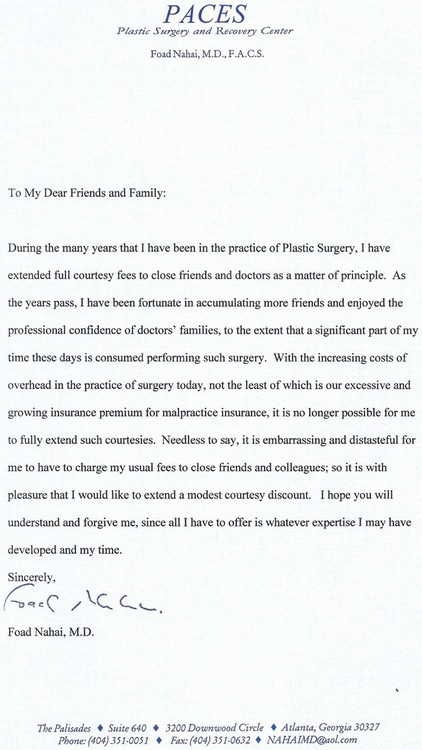

Friends or family as your cosmetic surgery patient

It is the practice of the senior author to discount my surgical fee for family, friends, other healthcare professionals, and office staff. However, the amount of discount that is offered will vary with the relationship. It can be embarrassing and challenging to discuss this face to face with the patient. To avoid this, I provide a letter to the patient explaining my position on this matter, which is a modified version of one which Dr. Tom Rees shared with me years ago (Fig. 1.6).