Chapter 10 The Relative Strengths of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Autografts and Allografts

Methods

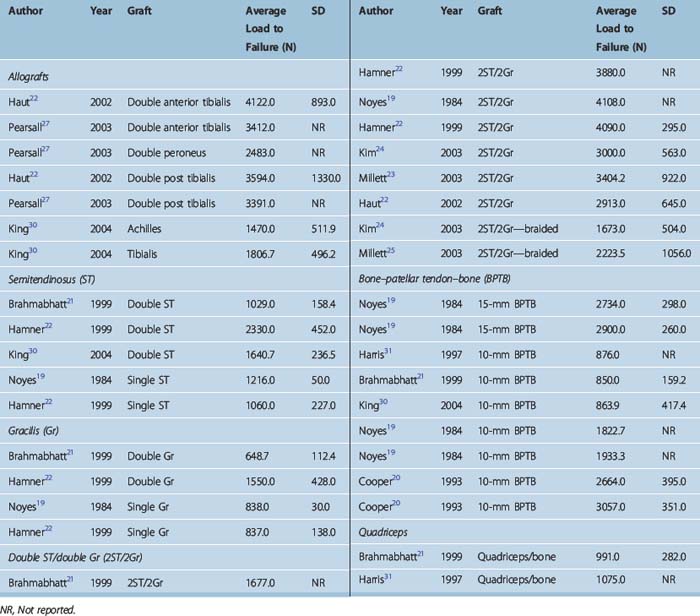

Table 10–1 summarizes the data that we were able to find in the literature on graft strengths. Load to failure (LTF) is the parameter compared in each case. This data was found from computerized literature searches targeting ACL reconstruction and each of the specific grafts in clinical use. Although some tissue banks have performed their own studies on graft strengths, we have purposely excluded such proprietary data and relied only on data published in the peer-reviewed literature to avoid bias.

Comparison of Graft Strengths

There is significant variability in LTF results among different studies for the same graft (see Table 10–1). This is likely related to differences in testing methodologies. Thus, it is necessary to look at the totality of the data to get an overall idea of relative graft strengths. Some of the authors have what appears to be outlier LTFs, but the relative strengths between grafts within their study generally reflect the bulk of the literature. The two main examples here are the data of Brahmabhatt21 and Harris, with low LTFs for all grafts tested relative to other studies. When comparing grafts it is important also to notice the configuration of the tested grafts; in other words, whether it is a single, double, or quadruple graft, and in the case of bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB), whether it is a 10-mm or 15-mm graft. The data in Table 10–1 also show that braiding of grafts has been shown to weaken rather than strengthen grafts and is not clinically indicated.

Effect of Ligamentization

Chapter 55 describes the effects of ligamentization on graft strength. Although there is some disagreement, it appears that grafts retain only about half their initial strength at long-term follow-up. Thus, grafts that are significantly stronger than the native ACL at time zero may indeed be necessary to produce ultimate strengths that are as strong as the ACL initially was. Indeed, some studies report a lower re-rupture rate for reconstructed ACLs than for the contralateral normal ACL,1 perhaps due to greater graft strength.

Allograft Strengths

Autograft strengths are relatively straightforward to measure. However, allograft strengths are more complicated because of the varying effects of graft preparation and sterilization techniques on the graft. Thus, any study that measures allograft strength can only be considered accurate for an allograft prepared in a similar manner. The relevant parameters may include radiated versus not radiated, the amount of radiation, and whether or not a radioprotectant was used. Other processes shown to significantly affect tissue properties include the use of cryoprotectant2 and even simple freezing.3 This is further complicated by the fact that these parameters may affect allograft strength at longer-term follow-up by influencing revascularization and cellular repopulation in addition to their effects at time zero. Thus, time zero data may not be sufficient for comparison between autografts and allografts, particularly in light of evidence that late failure rates may be higher for allografts than for autografts.4–7 The literature has also shown overall lower stability rates for allograft BPTB versus autograft BPTB,8–17 suggesting that ligamentization may weaken allografts more than autografts.18