CHAPTER 43 The ethnic rhinoplasty

History

Rhinoplasty, since its origins has been intimately tied to specific ethnicities. For example, John Roe1 used endonasal approaches to perform cosmetic rhinoplasty on the “pug nose” (referring to Irish patients who had excessive nostril show and a high nasolabial angle), while Jacques Joseph, modified tips and dorsal humps in Germany in the early 1900s.2 More recently, there have been numerous articles, documentaries, and media exposure over the popularity of rhinoplasty in Tehran, Iran, which is referred to by popular media as “the capital of nose jobs”.

In the United States, “standards of beauty” propagated by the mass media, are mostly based on Northern European facial traits with well-defined aesthetic goals (straight, narrow bridge, narrow and sharply defined nasal tip, a nasolabial angle of 90 to 95 degrees in men and 95–105 degrees in women). However, refining the nose of ethnic patients does not adhere to these European-based characteristics, which can lead to “racial incongruity”.3

“Racial incongruity” refers to an imbalance between the physical traits of individual and their ethnic background.3 A marked disproportion between nasal and facial morphology can be very conspicuous and awkward. For example, a sharp supra-tip break and an overly narrowed alar base in an African-American patient with Fitzpatrick 6 skin type, large jaws, and thick sebaceous skin, appears unnatural and over-operated. Many of the principles of avoiding an “over-operated” looking nose, are inherent to rhinoplasty as a whole. These concepts are even more critical in ethnic patients and racial incongruity can be prevented through proper preoperative evaluation and precise technical execution.

Many of the rhinoplasty lessons that we have learned and continue to improve upon have been by way of our non-Caucasian patients.1–16 Ethnic patients generally fall into two categories, those who want a “dramatic” difference without close attention to retaining their “ethnic” nose, and those who want subtle, natural refinement, without any loss of ancestral traits. The authors advocate a more “natural” approach to ethnic rhinoplasty. Furthermore, we feel that an open approach rhinoplasty works best for the complex, multidimensional nasal features of ethnic patients.3–9

African-American

Physical evaluation and anatomy

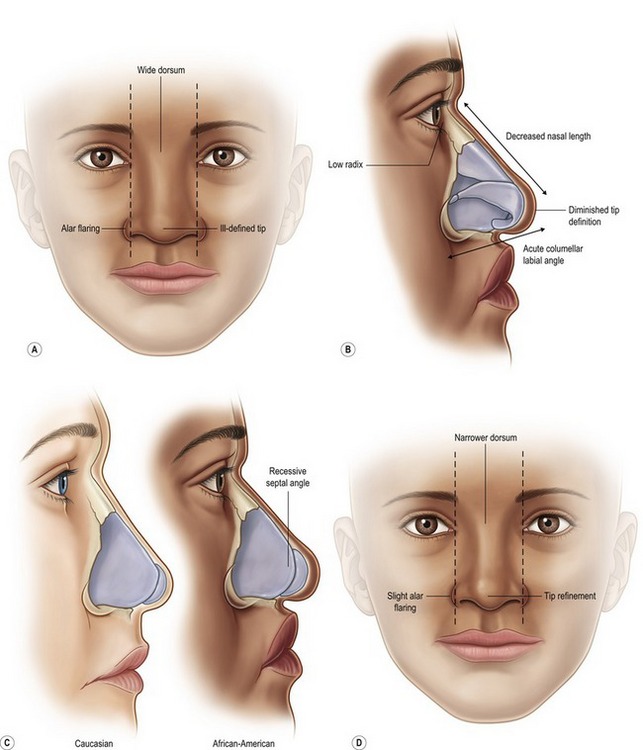

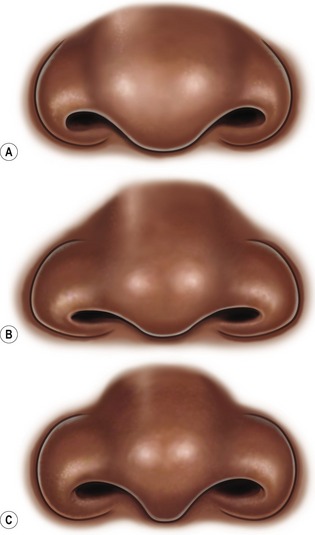

As with all rhinoplasty patients, the objectives should be clearly emphasized and discussed preoperatively. Ofodile and Bokhari5 have described a variable spectrum in anatomical traits of African-Americans depending on their origin. Rees6 observed that West Indies origination may influence the presence of a dorsal hump, which is very rare in African-Americans living in the United States. The African-American nose can typically be characterized by: thick, sebaceous skin/soft tissue, a shorter columella with less tip projection (rarely drooping), wide and flat dorsum (wide or non-distinct dorsal aesthetic lines), retrusive septal angle, alar flaring, wide interalar distance, bulbous tip, round nostrils, short nasal length, wide pyriform aperture, and bimaxillary protrusion (Fig. 43.1). In contradistinction to many Hispanic and Middle Eastern noses, African-American and Asian noses have a retrusive septal angle which can be beneficial in creating a pleasing tip-dorsum differential. Figure 43.2 depicts typical preoperative tip–alar relationships that should be recognized to prevent postoperative aesthetic complications. The osseous pyramid is often retrusive and wide. The presence and magnitude of these morphological traits should be closely evaluated, in addition to standard naso-facial analysis. Rohrich and Muzaffar3 have a clearly outlined and detailed study on African-American patients.

Technical steps

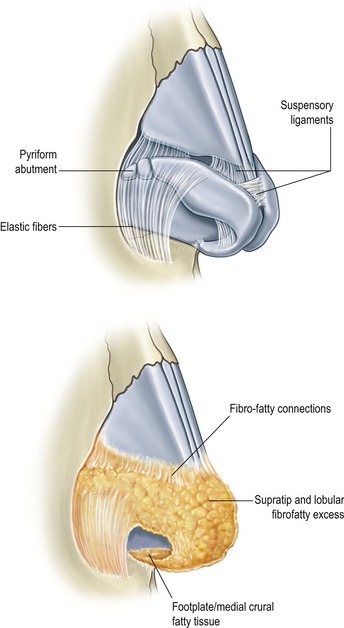

In general, African-American patients, like Asian patients, need augmentation in multiple dimensions. A common characteristic shared in varying degrees by each ethnic group in this chapter, is a thick, amorphous, and sebaceous skin/soft tissue nasal envelope and is best exemplified by the African-American nose. This weighs down the lower lateral, middle and medial crura, which can lead to prolonged swelling. Wide undermining is required for exposure, recruitment of nasal skin, and more even re-distribution of soft tissue healing forces (may aid in reduction of postop notching and buckling). The undersurface of the nasal skin, particularly in the supratip, domal, and paradomal region should be trimmed to, but not past the level of the subdermal plexus. Soft tissue debulking may improve the contractile ability of the skin to reveal the underlying framework established (Fig. 43.3). Taping and massage postoperatively plays an important role in limiting fibrous edema and thickened scarring between the skin and cartilage.

Dorsal aesthetic lines are just as important as tip shaping in African-Americans. The gold standard in dorsal augmentation is rib cartilage; however if the patient does not desire this, or does not require more than 6 mm of augmentation then the following methods can be employed: septal grafting with fascia or Alloderm (LifeCell Corp., Branchburg, NJ) overlay, Surgicel17 or fascia-covered diced cartilage,18 or silicone dorsal implant. We do not advocate the “L-shaped,” combination dorsal-tip projection silicone implant which has a higher extrusion and complication rate.

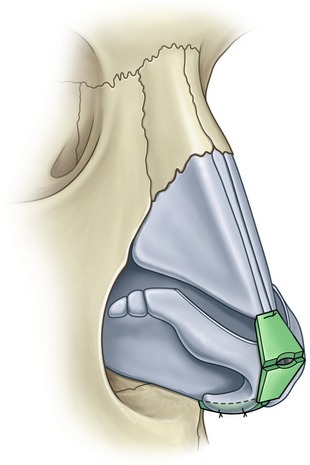

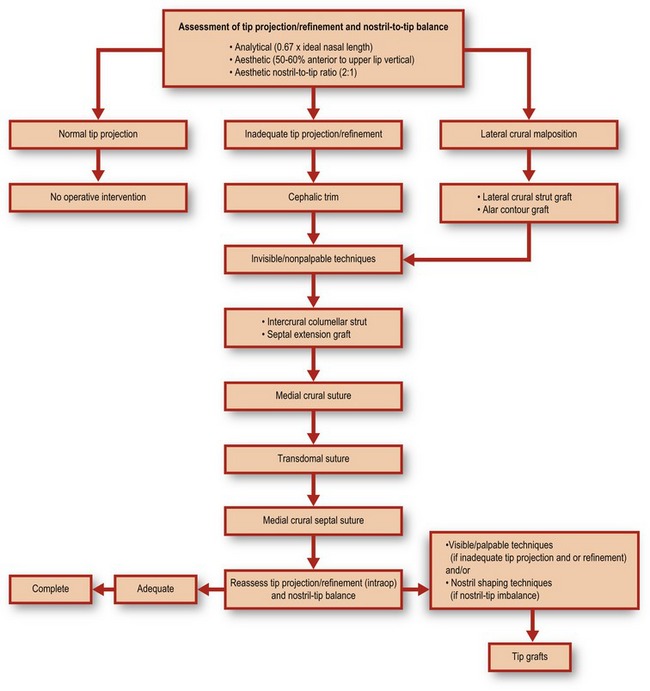

The new cartilaginous frame/shape must be established through maneuvers that increase tip support along with refinement. One benefit of the thick soft tissue coverage is that visible and more aggressive maneuvers can be used to improve tip shape and projection. A combination of tip suturing techniques are usually needed.19–22 A systematic approach is advocated to serve as a guide (Fig. 43.4). This begins with establishing tip platform strength via a columellar strut, medial crural sutures (MCS) and medial crural–septal sutures (MCSS)(if necessary for tip positioning). Transdomal sutures (TDS), interdomal sutures (IDS), and lateral crural spanning sutures (LCSS) are placed next. A helpful technique to improve alar arch strength is to overturn and suture the cephalic portion of the LLC to the native caudal rim strip instead of simple excision, known as a “lateral crural turnover flap”. This is a beneficial maneuver in ethnic patients because irregularities in the lower lateral crura are corrected while simultaneously improving rim support. Alar contour grafts are often needed to prevent notching at the soft triangle which can readily occur in African-American and Asian patients due to round nostril shape, and wide interalar distance that is later reduced. The excess alar soft tissue, when bent and medialized during tip shaping tends to buckle and addition of a crushed soft triangle graft may be needed.

Fig. 43.4 Tip algorithm. This serves as a general guide in performing systematic nasal tip shaping.

Adapted from Janis JE, Ghavami A, Rohrich A. A predictable and algorithmic approach to tip refinement and projection. In: Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ, Adams WP Jr, eds. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters, 2nd edn. St Louis, MO: Quality Medical, 2007.

Further tip refinement is established with a combined infratip lobular/onlay tip graft (Fig. 43.5). This will augment the deficient infratip lobule, improve tip projection and provide for necessary breakpoints. Septal cartilage is best and suture stabilization of the graft to the columellar construct and domes is recommended. Increased tip augmentation can be achieved by allowing the cephalad portion of the Gunter-type graft to project anterior to the domes. More cartilage grafts can be placed under this cephalad portion or as onlays. Additional crushed graft remnants can be placed after columellar closure, using a Bayonet forcep. Skin redraping throughout the process of tip shaping helps determine the influence of each maneuver on the external surface, which is the ultimate aesthetic goal.

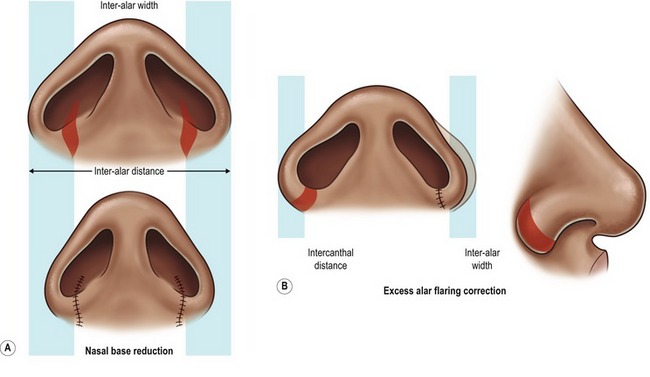

Lastly, enhancement of nostril shape and alar base reduction is almost always needed. Degree of alar flaring should be assessed according to how lateral to the medial canthus the flare is. Alar base resection is required when this is >2 mm (Fig. 43.6). Excision should not extend beyond the supra-alar groove where the lateral nasal artery travels. Closure using the “halving principle” is required. Excision amount should be measured with a caliper, and may be different on each side. Typically this measures between 6–12 mm. Extension into the nostril sill is needed when interalar distance is wide. Postoperative care will be discussed after all the ethnic nasal types have been addressed.

Case 1

African-American

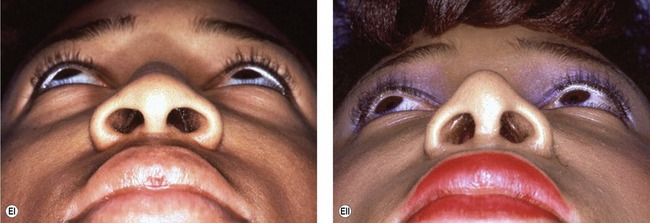

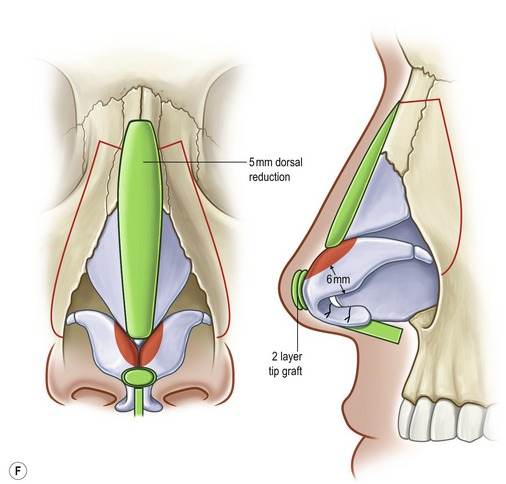

The patient demonstrates a wide dorsal hump and flat, poorly defined nasal tip (Fig. 43.C1). Alar base is wide. She also presents with a hanging ala and weak columella. There is a high dorsal hump and columellar-lobule disproportion. Internal exam was normal.

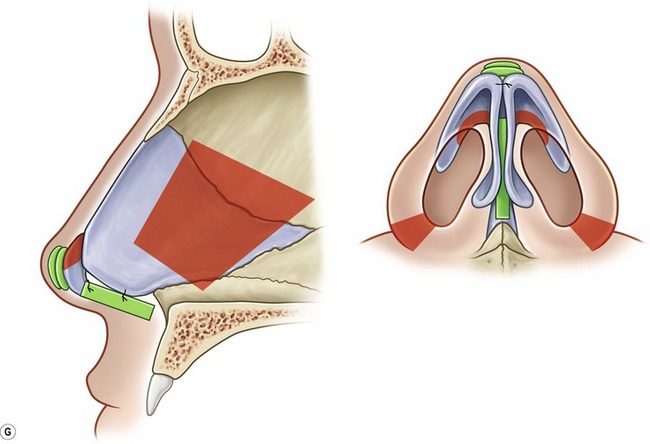

Fig. 43.C1 A, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. B, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. C, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. D, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. E, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. F, Intraoperative technique. G, Intraoperative technique. Red, resection/excision; Green, augmentation/grafts.

Operative steps

• Open approach with stair-step transcolumellar incision joined to bilateral infra-cartilaginous incisions.

• Component reduction of dorsum (5 mm).

• Cephalic resection of lower lateral cartilage, preserving 6 mm rim strips.

• Floating columellar strut graft stabilized to repositioned (more anteriorly projecting) medial crura with polydioxanone sutures.

• Graduated, sequentially-placed transdomal and interdomal “shaping” sutures.

• Onlay tip grafts x3, stabilized with sutures.

• Lateral osteotomies (low to high).

Hispanic

Introduction

Hispanics make up the largest proportion of ethnic minority groups in the United States. In areas such as Los Angeles and Miami, Hispanic patients are one of the largest groups seeking cosmetic surgery. Aside from post-partum modifications such as body and breast contouring, rhinoplasty is becoming a more acceptable way to achieve a refined elegance and balance to the face. Similar to Middle Eastern patients, this ethnic group requires detailed preoperative planning to delineate the significant characteristics that warrant alteration. An over-operated appearance is commonly seen by surgeons that perform similar maneuvers in every ethnic type, without regard for the anatomical distinctions. As a whole, Hispanic patients are very appreciative, and realistic about the postoperative expectations.

Physical evaluation and anatomy

A classic Hispanic rhinoplasty study is that of Fernando Ortiz-Monasterio on the Mestizo nose.11 Ortiz-Monasterio11 lists five characteristics that differ from Caucasian noses: (1) thick, sebaceous soft tissue envelope; (2) small osseocartilaginous vault; (3) weak tip support due to short medial crura and weak caudal septum; (4) short, hidden columella; and (5) broad alar base and round nostrils. He advocates an intracartilaginous approach with supportive grafts, struts, minimal dorsal augmentation, and nostril/sill correction. Since that seminal manuscript, further ethnic and morphological delineations have been made by Sanchez23 (“Chata”-Caribbean nose, predominant “Black” or “Asian” features) and Milgrim.24 Milgrim24 divides the Hispanic female nose into three subtypes based on geographical origin: Caribbean, Central American, and South American.

Daniel15 reported on his experience with primarily Mexican-American patients and classified them into three types: Type 1 – (Castilian) high arched osseocartilaginous dorsum and normal tip projection; Type 2 – (Mexican-American) low radix and underprojecting tip with the illusion of a large dorsal hump; Type 3 – (Mestizo) thick skin envelope, dorsal-tip disproportion, amorphous, wide base. While classifications are less relevant, an analysis-based treatment plan is imperative in this ethnic group. In addition, those with more African-American (Caribbean-Creole) features tend to be more wary of significant nasal modification, sometimes citing noses of notable African-American celebrities that display extreme “racial incongruity”.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree