CHAPTER 54 The dual plane approach to breast augmentation

History

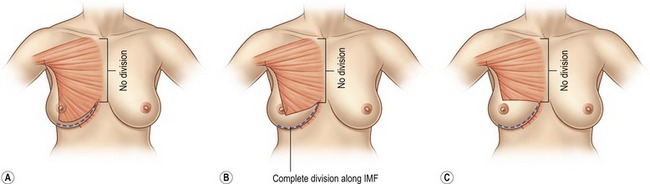

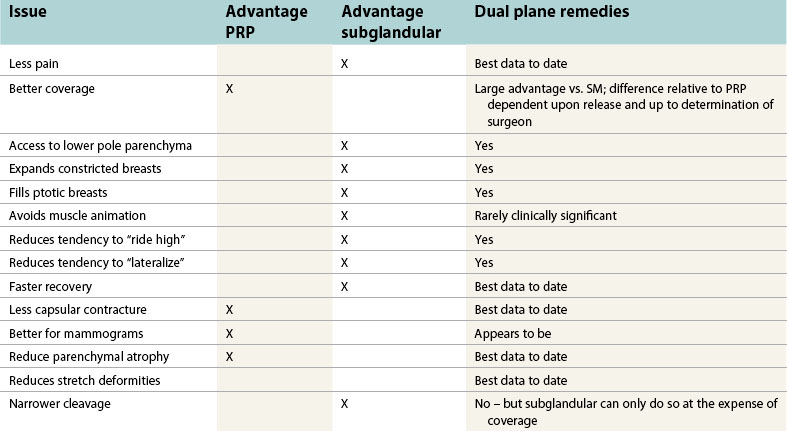

While submammary and partial retropectoral are “pure” extremes, the dual plane is a continuous spectrum of options, occupying the “gray-zone” in between. The operation starts with the creation of a partial retropectoral pocket. The origins are carefully divided along the inframammary fold, which allows the cut edge of the muscle to glide a bit superiorly, so that there is both a small submammary and a large subpectoral area of the pocket, and hence the term dual plane. By disrupting attachments of the muscle to the overlying gland, the muscle can be gradually and incrementally raised, thereby reducing the proportion of subpectoral pocket and increasing the proportion of submammary pocket. The purported advantages of the partial retropectoral pocket are predominantly coverage along the sternum and over the superior border of the implant; the dual plane preserves these. The purported advantages of the submammary pocket are to direct implant pressure upon the lower pole; the dual plane preserves these as well (Fig. 54.1).

Criteria for the ideal pocket

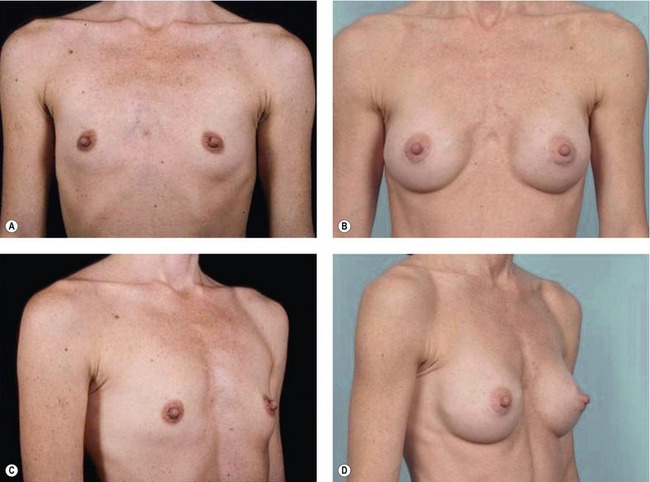

Over the last several decades, published reoperation rates in PMA studies have not changed despite the use of different implants, remaining consistently at about 20% at three years. In a study of one device, a single surgeon achieved a 0% 3-year reoperation rate in contrast to an average of 13.9% for all the doctors in the study. Taken together, these two findings demonstrate that the outcome in breast augmentation is determined far less by the type of the device than by other factors (Fig. 54.2).

Finally, outcomes need to be assessed at long intervals after surgery. Irrevocable, permanent, progressive, and at times totally uncorrectable changes occur to a breast years after an augmentation. Adequacy of tissue coverage needs to be judged at the longest possible intervals, decades if possible. Such long-term data is meager, but owing to the importance of such lifelong changes on the breast, at this point anecdote and extrapolation of shorter-term results should be considered (Fig. 54.3; Table 54.1).

Pain and recovery

When these same techniques are applied to the submammary approach, patients typically feel slightly less stiff and sore than do dual plane patients, but both groups still consistently achieve a “24-hour” recovery. Any difference is subtle, noted only for a day or two, and is of no real consequence, particularly relative to advantages of achieving more muscle coverage.

Coverage and stretch

Soft tissue coverage is the single-most important issue affecting the short and long-term result after a breast augmentation. With adequate coverage, the implant edges are less visible, and the breast looks more natural and less augmented. Any folds or irregularities with the implant shell are more concealed. With more tissue over it, the device is less palpable. With less tissue coverage, the edges of the implant are more visible, the breast looks more augmented, and it is easier to feel the implant (Fig. 54.4).

Over the long term, these changes become more profound. Implants put pressure on the breast, and the parenchyma gradually compresses and atrophies. The presence of the implant stretches and thins skin. This occurs with implants in all positions. No study will ever randomize patients of similar tissue types and implant sizes and follow them over enough time for a scientific conclusion to be made. But a large amount of clinical observation and logic (see Fig. 54.3 and Fig. 54.5) offers us guidance.

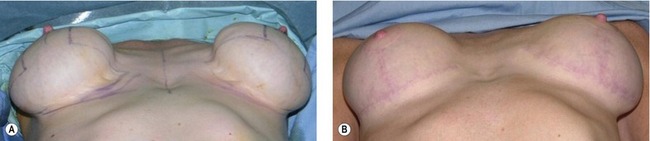

Examples of submammary patients with severe parenchymal atrophy abound, while retropectoral patients with similar characteristics are rarely seen. And when they are, though the implants may have ostensibly been placed “behind the muscle”, secondary surgery frequently reveals that the muscle has been avulsed off both the inframammary fold and sternum, thereby sacrificing the critical coverage of which we are speaking (Fig. 54.6).

These problems are sometimes noticeable within a year or two, but can often take years more to develop. We must be aware of these problems and remind ourselves that we need to create a result that will look good not just for years, but for decades. As someone who sees many secondary problems, I can state categorically that subglandular patients present more frequently, with more severe problems, and with more unsolvable problems than do subpectoral or dual plane patients.

Such tissue thinning with submammary patients also is a set up for a problem which is difficult to correct, as to do so often requires a switch to the partial retropectoral or dual plane position. But once there is a subglandular pocket, the coverage in the retropectoral pocket is forever impaired. Though one can use sutures to tack the muscle back up to the gland, its caudal cut edge can never be retained as caudally as it might have been were this not to have happened, thereby forever impairing inferior coverage. Marionette pullout sutures have been described to hold down the muscle in this situation, but this also cannot achieve the same degree of coverage as if the attachments between the muscle and the overlying gland were never disrupted (Fig. 54.7).

In conjunction with the thinning, there is often progressive stretch of the skin envelope, sometimes necessitating mastopexy. Even if this mastopexy would have been inevitable in the future with a partial retropectoral or dual plane pocket, such patients frequently have soft tissue thinning or capsular contractures in addition to the stretched skin. This necessitates a pocket change and possible capsulectomy in addition to the mastopexy, which can be a riskier procedure than if the implant had started out dual plane or partial retropectoral. This combination of secondary revision occurs so frequently that efforts must be made at the time of the original surgery so that this doesn’t happen (Fig. 54.8; also see Fig. 54.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree