CHAPTER 44 The Asian rhinoplasty

Introduction

Asian rhinoplasty is distinguished from other ethnic groups based on differences in anatomy, individual aesthetic goals, and surgical technique. Anatomical features of Asians include thicker skin, weaker cartilages, less dorsal projection, rounder tip and alae, and a more retrusive columella.1,2 Asian patients seeking rhinoplasty typically present with the chief complaint of a flat, wide nose and bulbous tip. Their aesthetic goals are to raise the dorsum, to increase tip projection, and refine the tip contours while still maintaining their ethnic appearance.

Surgical techniques, aimed at strengthening and augmenting the weaker cartilage framework, have supplanted traditional reductive techniques described for the over-projected Caucasian nose.3 Controversy over an ideal technique has divided practitioners, principally based upon material preference: alloplastic implants versus autogenous grafts. The most common material used worldwide is currently silicone alloplast formed as either an L-shaped implant to augment both the dorsum and support the columella or a straight (I-shaped) dorsal onlay implant. Other alloplastic materials include expanded polytetrafluoroethylene [ePTFE] (Surgiform Technology, Ltd., Columbia, South Carolina) and porous high density polyethylene, Medpor® (Porex Corp., Newnan, Georgia). Autogenous tissue options have included cartilage (septal cartilage, auricular cartilage, costal) and bone (split-calvarium, iliac crest, olecron, costal) sources.1,4,5 The senior author’s preferred method is costal cartilage because of its abundant availability, mechanical strength, and resistance to infection, resorption or extrusion.

Physical evaluation

Anatomy

Deep to this layer is the nasal skeleton of bone and cartilage. The bony dorsum, which makes up the superior third of the nose, is comprised of paired nasal bones attached to the frontal process of the maxillary bones laterally and the nasal process of the frontal bones superiorly. The inferior two-thirds of the nasal skeleton is cartilaginous, including the septum, paired upper lateral, lower lateral, and sesamoid cartilages. The quadrangular cartilaginous septum connects with the anterior bony skeleton through the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone superiorly, the vomer bone posteriorly, and the maxillary crest inferiorly. Supporting the dorsum lateral to the septum are the upper lateral cartilages, which attach to the undersurface of the nasal bones superiorly, the pyriform aperture laterally, and are continuous with the cartilaginous quadrangular septum medially. The inferior edge of the upper lateral cartilages join the lower lateral cartilages in the “scroll area” caudally. The lower lateral cartilages are paired arches that join medially by fibrous connections within the columella. Connections also exist between the medial crura and caudal cartilaginous septum.

Consideration of the entire face must not be ignored when evaluating a patient for rhinoplasty. The nose is the central feature of the face; and thus, should be reshaped in harmony with the overall facial dimensions and contours. The anatomic aesthetic subunits of the nose include the median structures (dorsum, tip, and columella) and paired lateral structures (nasal side walls, alae, and soft triangle facets). In contrast to Caucasians, Asians typically do not have a well-demarcated soft tissue triangle or nasal sill, and the lower dorsal profile tends to blend the sidewall into the cheek.6 Other differences include a lower lying radix, greater alar width, and more extreme nasolabial angles. The nasolabial angle is more obtuse in Asian females, but more acute in Asian males compared to Caucasians.7 The overall structural support in the Asian nose is weaker when compared to Caucasians. The lower lateral cartilages are weaker and the quadrangular cartilage is both thinner and smaller. Thus, septal cartilage alone as a source for augmentation grafting material is typically inadequate.

Technical steps

Cartilage harvest

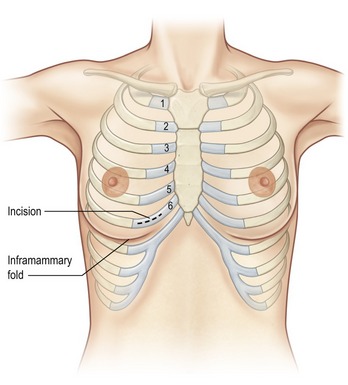

Costal cartilage harvest typically precedes the nasal surgery in order to maintain sterility and decrease the possibility of cross-contamination from the nose to the chest. Several choices exist when harvesting costal cartilage. Cadaveric studies have advocated harvesting the seventh rib as an ideal choice because of its superior length, greater thickness, and its location inferior to the lung pleura and lateral to the course of the internal mammary artery.8 The senior author prefers the sixth rib due to its close proximity to the inframammary crease (Fig. 44.1). Sometimes both sixth and seventh ribs are harvested through a single common incision when a large amount of grafting material is required (e.g. grafts for dorsal and premaxillary augmentation). The fifth rib has the benefit of fewer connections to neighboring ribs, but it tends to be more curved and shorter than the sixth rib. Selection of the rib is thus case specific and depends upon accessibility, presence of calcifications, volume of graft required, and rib configuration.

Preoperatively, a thorough history should include questions about previous chest surgery, breast augmentation, and type of breast implants if present. In the female patient, breast size can limit the surgeon’s ability to adequately expose the more superiorly situated ribs. Access is further complicated by the presence of implants that both increase the breast size and require a more inferior dissection path in order to avoid entering the implant capsule.

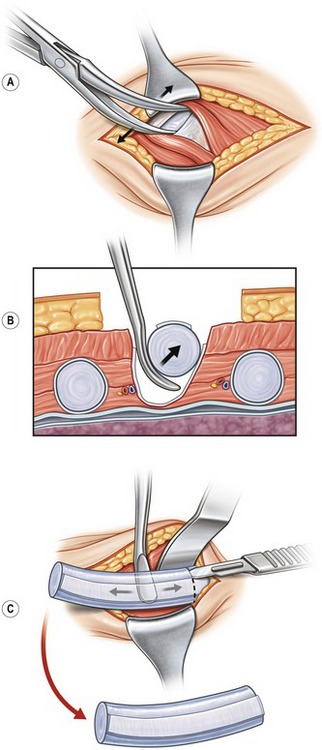

The harvesting procedure begins with the skin incision and sharp dissection through subcutaneous adipose and breast tissue down to the pectoralis muscle fascia. The fascia is sharply divided and the muscle fibers are bluntly spread using a hemostat (Fig. 44.2A). Blunt dissection with a cotton dissector clears the remaining soft tissue off the rib to expose the perichondrial surface. The osseous junction is confirmed using a 27-gauge needle, and this landmark marks the lateral most extent of the useful costal cartilage. The perichondrium is incised along the osseochondral junction and along the superior and inferior edge of the anterior surface of the rib to create a “window” through the perichondrium to the cartilage below. The strip of perichondrium within this window is elevated with a Freer elevator, excised in a 5–8 cm length, and stored in sterile saline for later use. Next, the rib is dissected away from the remaining perichondrium circumferentially, taking care to avoid injury to the deep perichondrium, which intimately overlies the lung pleura (Fig. 44.2B). An incision is made halfway through the rib just medial to the osseochondral junction. A medial incision is also made based on the length of cartilage required for the augmentation (Fig. 44.2C). A blunt-tipped Freer elevator is used to complete the cartilage incisions and dissect through the neighboring rib costal attachments. This isolates the dissected segment of costal cartilage, which is removed and set aside in sterile saline to soak. Attention is then directed to the medial and lateral margins of the in-situ rib. A rongeur is used to bevel the sharp edges, which prevents potential visibility or edge palpability. Irrigation solution is then instilled into the surgical bed and the anesthesiologist is asked to perform a Valsalva maneuver. If there were any openings into the pleural space, bubbles in the irrigation fluid would indicate an air leak. Closure of the wound is deferred until the end of the procedure in case additional rib or perichondrium is needed. The wound is lightly packed with a moistened cotton gauze and covered to maintain sterility.

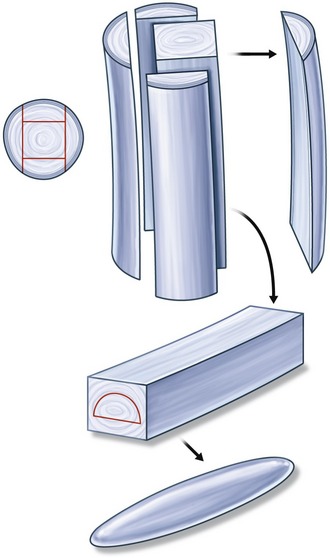

The most technically challenging aspect of augmentation rhinoplasty using costal cartilage is carving the grafts. Costal cartilage must be carved sequentially, over several hours, with frequent soaking periods to allow the natural warping tendencies of each piece to be declared. The dorsal graft must have minimal warping, and is best carved from the central core of the rib.9,10 (Fig. 44.3).