Chapter 2 Teamwork for total burn care

Burn centers and multidisciplinary burn teams

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Introduction

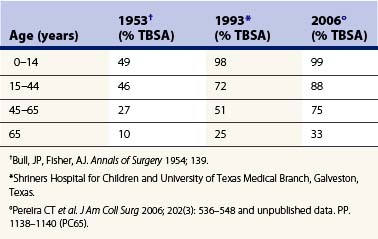

Severe burn injuries evoke strong emotional responses in most people, including health professionals, who are confronted by the specter of pain, deformity, and potential death. Intense pain and repeated episodes of sepsis, followed either by death or by survival encumbered by pronounced disfigurement and disability, have been the expected sequelae to serious burns for most of mankind’s history.1 However, these dire consequences have been ameliorated so that, although burn injury is still intensely painful and sad, the probability of death has been significantly diminished. During the decade prior to 1951, young adults (15–43 years of age) with total body surface area (TBSA) burns of 45% or greater had a 49% mortality rate (Table 2.1).2 Forty years later, statistics from the pediatric and adult burn units in Galveston, Texas, show that a 49% mortality rate is associated with TBSA burns of 70% or greater in this age group. Over the past decade, mortality figures have decreased even more dramatically, so that almost all infants and children can be expected to survive when resuscitated adequately and quickly.3 Although improved survival has been the primary focus of advances in burn treatment for many decades, that goal has now been virtually accomplished. The major goal is now rehabilitation of burn survivors to maximize quality of life and reduce morbidity.

Table 2.1 Percent total body surface area (TBSA) burn producing an expected mortality of 50% in 1952, 1993, and 2006

Such improvement in forestalling death is a direct result of the maturation of burn care science. Scientifically sound analyses of patient data have led to the development of formulas for fluid resuscitation4–6 and nutritional support.7,8 Clinical research has demonstrated the utility of topical antimicrobials in delaying the onset of sepsis, thereby contributing to decreased mortality in burn patients. Prospective randomized clinical trials have shown that early surgical therapy is efficacious in improving survival for many burned patients by reducing blood loss and diminishing the occurrence of sepsis.9–14 Basic science and clinical research have helped reduce mortality by characterizing the pathophysiological changes related to inhalation injury and suggesting treatment methods that have reduced the incidence of pulmonary edema and pneumonia.15–18 Scientific investigations of the hypermetabolic response to major burn injury have led to improved management of this life-threatening phenomenon, not only enhancing survival, but also promising an improved quality of life.19–32

Melding scientific research with clinical care has been promoted in recent burn care history, largely because of the aggregation of burn patients into single-purpose units staffed by dedicated healthcare personnel. Dedicated burn units were first established in Great Britain to facilitate nursing care. The first US burn center was established at the Medical College of Virginia in 1946. In the same year, the US Army Surgical Research Unit (later renamed the US Army Institute of Surgical Research) was established. Directors of both centers and later, the founders of the Burn Hospitals of Shriners Hospitals for Children, emphasized the importance of collaboration between clinical care and basic scientific disciplines.1

Findings from the group at the Army Surgical Research Institute point to the necessity of involving many disciplines in the treatment of patients with major burn injuries and stress the utility of a team concept.1 The International Society of Burn Injuries and its journal, Burns, as well as the American Burn Association and its publication, Journal of Burn Care and Research, have publicized the notion of successful multidisciplinary work by burn teams to widespread audiences.

Members of a burn team

Patients and their families are infrequently mentioned as members of the team but are obviously important in influencing the outcome of treatment. Persons with major burn injuries contribute actively to their own recovery, and each brings individual needs and agendas into the hospital setting that may influence the way treatment is provided by the professional care team.33 The patient’s family members often become active participants. This is obvious in the case of children, but also true in the case of adults. Family members become conduits of information from the professional staff to the patient. At times, they act as spokespersons for the patient, and at other times, they become advocates for the staff in encouraging the patient to cooperate with dreaded procedures.

With so many diverse personalities and specialists potentially involved, purporting to know what or who constitutes a burn team may seem absurd. Nevertheless, references to ‘burn team’ are plentiful, and there is agreement on the specialists and care providers whose expertise is required for optimal care of patients with significant burn injuries (Figure 2.1a and 2.1b).

Figure 2.1a, b Experts from diverse disciplines gather together with common goals and tasks, having overlapping values to achieve their objectives.

Burn surgeons

The ultimate responsibility and overall control for the care of a patient lies with the admitting burn surgeon. The burn surgeon is either a general surgeon or plastic surgeon with expertise in providing emergency and critical care, as well as in performing skin grafting and amputations. The burn surgeon provides leadership and guidance for the rest of the team, which may include several surgeons. This leadership is particularly important during the early phase of patient care, when moment-to-moment decisions must be made based on the surgeon’s knowledge of physiologic responses to injury, current scientific evidence, and appropriate medical/surgical treatments. The surgeon must not only possess knowledge and skill in medicine, but also be able to exchange information clearly with a diverse staff of experts in other disciplines. The surgeon alone cannot provide comprehensive care, but must be wise enough to know when and how to seek counsel as well as how to give clear and firm direction to activities surrounding patient care. The senior surgeon is accorded the most authority and control of any member of the team, and thus bears the responsibility and receives accolades for the success of the team as a whole.33