Type I

Incomplete fusion resembling a pseudarthosis

Type II

Fusion with a notch of varying depth

Type III

Complete fusion of lunate and triquetrum alone

Type IV

Complete fusion associated with other carpal anomalies

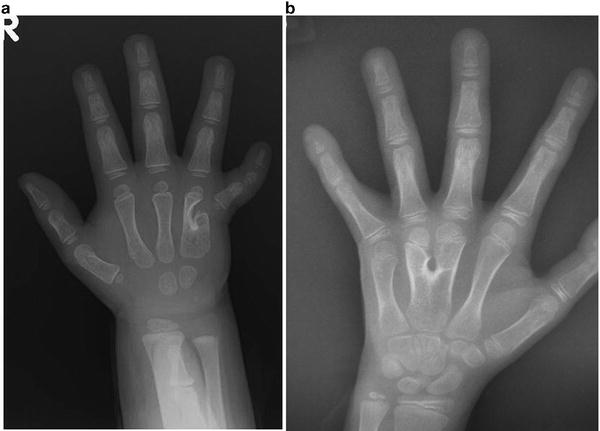

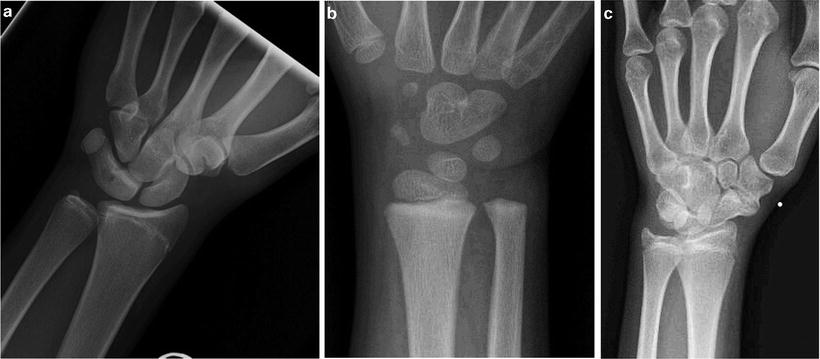

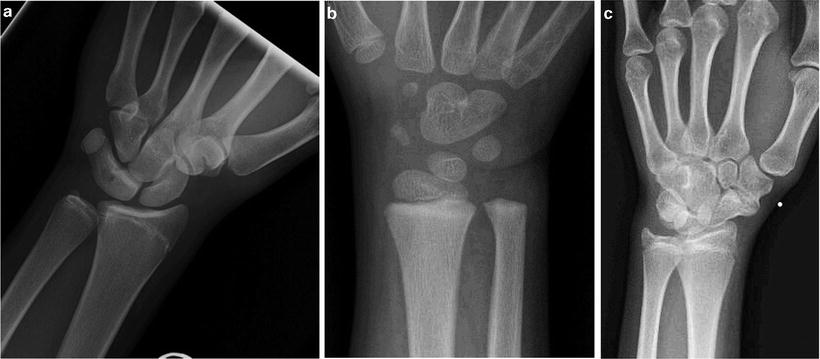

Carpal coalitions can occur in isolation or associated with syndromes. Isolated coalitions have been described between all adjacent carpal bones [3, 7, 8, 13, 21–28]. More commonly, the non-syndromic coalitions involve only two bones (Fig. 17.1a, b), usually within the same carpal row, while syndrome-associated coalitions often include multiple bones (see Fig. 17.1c).

Fig. 17.1

(a) Incomplete coalition between lunate and triquetrum (Minnaar type II). (b) Incomplete coalition between capitate and hamate. (c) Multiple coalitions—capitate and hamate; scaphoid and trapezium

Isolated Carpal Coalitions

The most common isolated carpal coalition is between the lunate and triquetrum [14, 29]. The majority of these coalitions are bilateral, asymptomatic, and incidental findings; most require no treatment. However, there is growing evidence that incomplete coalitions are more susceptible to injury and hence can become symptomatic [2, 5, 7, 14, 20]. Incomplete coalition is likely the result of a failure of separation during early fetal development, with the degree of cellular death dictating the type of coalition which will develop [5, 8, 13, 16]. Ritt et al. [14] believe that the incomplete coalitions are covered by a thin layer of articular cartilage that in time can wear down and lead to localized degenerative arthritis or be unusually susceptible to fracture. In patients who have symptomatic incomplete coalitions between the lunate and triquetrum, lunato-triquetrum (LT) fusion is recommended. LT fusion provides predictable improvement of symptoms, with little loss of motion [5, 12, 14, 20].

Less common is a coalition between the hamate and pisiform. The first case in the English literature was described by Cockshott as an isolated asymptomatic entity [9]. However, subsequent authors have reported ulnar side symptoms, including pain and/or parasthesias [7, 10, 11, 30, 31]. According to Burnett, ulnar neuropathy was more frequent in non-osseous hamate-pisiform coalitions compared to those displaying an osseous coalition [10, 31]. In addition, non-osseous coalitions may be more susceptible to degenerative arthritis given the abnormal joint mechanics and the thin cartilage surfaces between the affected carpals [10, 30]. The literature suggests that patients with an osseous hamate-pisiform coalition are predisposed to fracture [7, 10, 30]. An acute symptomatic hamate-pisiform coalition should be initially treated by conservative therapy (typically immobilization). If immobilization does not resolve the pain, then treatment should consist of excision of the pisiform and accompanying coalition [7, 10, 11].

Syndromes Associated with Coalitions

Carpal coalitions are seen in patients with a variety of syndromes:

1.

Arthrogryposis

2.

Diastrophic dwarfism

3.

Dyschondrosteosis

4.

Ellis–Van Creveld syndrome

5.

Hand-foot-genital syndrome

6.

Fetal alcohol syndrome

7.

Oto-palato-digital syndrome

8.

Turner syndrome

Typically, the syndrome-associated coalitions involve multiple carpal bones, cross-carpal rows, and are often associated with other anomalies in the involved extremity as well as anomalies of other organ systems [5, 22, 29].

Ellis–van Creveld Syndrome

Also known as chondro-ectodermal dysplasia, Ellis–van Creveld syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder with characteristics of disproportionate dwarfism, congenital heart disease, dysplastic nails and teeth, polydactyly, and other hand anomalies [22, 32–35]. The disorder has variable expression with genetic defects in the EVC1 and EVC2 genes, which are located on chromosome 4p16 [33, 35].

The incidence of Ellis–van Crevald Syndrome is estimated to be 1 in 60,000 live births, with boys and girls equally affected. The radiographic findings include delayed bone maturation and particularly involve the lateral tibial condyle, leading to genu valgum [35, 36]. Additional radiographic findings include shortened ribs, a trident acetabular roof, and premature ossification of the femoral heads. Although not specific for Ellis–van Creveld syndrome, findings on hand radiographs include coalition of the hamate and capitate, postaxial polydactyly, fusion of metacarpals, and clinodactyly of the small finger.

Treatment focuses on the congenital heart disease and respiratory changes secondary to the thoracic insufficiency. These children typically require early removal of neonatal teeth to help with feeding. The postaxial polydactyly is treated based on the physical findings [35]. No treatment is required for the carpal coalition.

Syndromes with Carpal and Tarsal Coalitions

The combination of carpal and tarsal coalitions can occur in several conditions, including: hand-foot-genital syndrome, symphalangism, and arthrogryposis.

Hand-Foot-Genital Syndrome

Hand-foot-genital syndrome (formerly hand-foot-uterus syndrome) was first described in 1970 in four generations of a single family [37]. Hand-foot-genital syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by a nonsense mutation in HOXA13 [38]. Both males and females can be affected. In females there may be duplication of the genital tract and other abnormalities involving the ureters and urethra. Males may present with hypospadias of variable severity [39, 40]. Abnormalities in the lower limb consist of small feet with short great toes and tarsal coalitions. The upper extremity includes shortened, somewhat stiff thumbs. Clinically the thumb is proximally placed with a hypoplastic thenar eminence; the index finger is ulnarly deviated, while the small finger often demonstrates clinodactyly and brachydactyly. Delayed ossification and coalition of the carpal bones, specifically the scaphoid and trapezium may be noted. Surgical intervention for the limb deformities is usually not necessary, but these patients do need urologic evaluation [40].

Symphalangism

Symphalangism is an uncommon condition characterized by fusion of the interphalangeal joints of the hands and feet [41, 42]. The term was first used by Harvey Cushing in 1916 to describe a family with ankylosis of the interphalangeal joints of the hand [43, 44]. Two types of symphalangism are recognized: proximal and distal. This refers to the proximal interphalangeal joint (most common) or the distal interphalangeal joint; either form is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern [41, 42, 45]. Clinically, patients will have limited or no motion across the interphalangeal joint without flexion creases. Radiographs prior to skeletal maturity may suggest a joint space but as the cartilaginous bridge between phalanges ossifies as the skeleton matures, bony continuity across the joint will be apparent [42].

Flatt and Wood described three forms of symphalangism [45]:

1.

True symphalangism without additional skeletal abnormalities

2.

Symphalangism associated with symbrachydactyly

3.

Symphalangism with syndactyly

The small finger is most commonly affected, followed by the ring, long, and index fingers [41, 45, 46].

Multiple additional skeletal abnormalities have been reported in association with symphalangism, including: brachydactyly, camptodactyly, clinodactyly, syndactyly, radiohumeral fusion, carpal coalitions, pes planus, bilateral hip dislocation, tarsal coalitions, cervical and thoracic spinal fusions [41, 42]. The most common carpal coalition occurring in association with symphalangism is triquetrum-hamate; capitate-hamate and capitate-trapezium, triquetrum-lunate, and scaphoid-trapezium coalitions have also been reported [22, 44, 47]. Despite the radiographic appearance, fusion of the phalanges in symphalangism rarely impairs hand function.

Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita

Arthrogryposis multiplex congenital encompasses several conditions of differing etiology and mixed clinical features. Common to each type are multiple congenital contractures in multiple body areas [48, 49]. The term “arthrogryposis” is more of a description of clinical findings than a specific diagnosis, with the overall prevalence being one in 3,000 live births [49, 50]. The etiology of arthrogrypotic syndromes is presumed to be multifactorial resulting in limitation of fetal movement. The resultant effect is loss of muscle mass with imbalance of muscle power across joints, which provokes a collagen response. This in turn leads to partial replacement of muscle volume and collagenous thickening of joint capsules and finally joint fixation [51].

Although tarsal coalitions can occur in arthrogryposis, carpal coalitions are more common [22]. The coalitions can be variable, with the proximal carpals involved first and then more extensive involvement between rows [22]. Newcombe et al. [52] reported that these carpal coalitions seen in arthrogryposis are likely acquired rather than congenital. They dissected specimens and found evidence of some remnants of joint space. Another theory is that the continued stretching and splinting in these patients causes fractures which lead to eventual coalitions.

The typical patient with arthrogryposis will have a flexed and ulnarly deviated wrist. Most of these patients will have a rigid flexion deformity and are resistant to nonoperative treatment. [53]. As these patients mature, the midcarpal joint can become obliterated from the multiple carpal coalitions. Coalition between the scaphoid and capitate is frequently observed. The presence of this coalition makes proximal row carpectomy impossible in these children [53]. Ezaki and Carter [53] describe a biplanar wedge resection of the carpus designed to extend the wrist and correct the ulnar deviation. Timing of surgery is recommended before the child reaches preschool age.

Isolated carpal coalitions are usually asymptomatic; however, when they form partial coalitions, they are more susceptible to injury. Partial coalitions, refractory to conservative treatment, can be either excised or fused (depending on their location) with good success. Syndrome-associated carpal coalitions tend to involve both carpal rows, though few require surgical intervention.

Metacarpal Synostosis

Metacarpal synostosis is an uncommon congenital hand malformation characterized by the coalescence of adjacent metacarpals [54]. It most often involves the ring and little finger metacarpals. The condition can be found in isolation or in association with other hand abnormalities, including: polydactyly, radial and ulnar deficiencies, cleft hand, and Apert syndrome [54–57]. Isolated metacarpal synostosis is most often sporadic, though cases have been described that suggest familial inheritance in either X-linked recessive [55, 58] or autosomal dominant patterns [59]. In patients with X-linked recessive inheritance, recent exome sequencing detected a nonsense mutation in exon 3 of FGF16, which is part of the Xq21.1 chromosome [58]. Jamsheer et al. [58] also concluded that FGF16 may play a role in fine tuning the human skeleton of the hand.

Physical Findings

The condition most commonly occurs between the ring and little finger metacarpals (Fig. 17.2). Typically the little finger is short, hypoplastic, with limited range of motion, and held in an abducted position. This awkward abducted position limits digital dexterity and may disturb hand function, for example: getting the digit caught in pockets and other enclosed spaces [54, 55, 60]. In addition, some patients have noticed that small objects may fall through their hands, more commonly seen in middle-ring finger metacarpal synostosis [54].