Most superficial fungal infections of the skin are caused by dermatophytes or yeasts. They rarely cause serious illness, but fungal infections are often recurrent or chronic in otherwise healthy people. The availability of effective over-the-counter antifungal medications has been helpful to people with actual fungal infections, but these medications are frequently used by people who actually have other skin diseases such as dermatitis. One of the main diagnostic problems with fungal infections is that they closely resemble dermatitis and other inflammatory disorders. Both clinicians and patients overdiagnose and underdiagnose fungal infections. A few simple clinical points can help avoid misdiagnoses:

Many inflammatory skin diseases such as nummular dermatitis present with an annular pattern and are often misdiagnosed as tinea corporis.

Dermatitis and dermatophyte infections on the feet have a very similar appearance. However, the presence of toe web scale and nail plate thickening is more characteristic of a fungal infection.

Half of all nail disorders are caused by fungus. The other causes of nail diseases such as psoriasis and lichen planus may appear very similar to fungal infections.

Fungal infections are rare on the hands, but when they do occur they are almost indistinguishable from irritant contact dermatitis or dry skin.

Fungal infections on the scalp are rare after puberty.

The diagnosis of a suspected fungal skin infection should be confirmed with a potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination or fungal culture.

Dermatophytes can penetrate and digest keratin present in the stratum corneum of the epidermis, hair, and nails. Superficial dermatophyte infections are a common cause of skin disease worldwide, especially in tropical areas. The names of the various dermatophyte infections begin with “tinea,” which is a Latin term for “worm.” The second word in the name is the Latin term for the affected body site:

Tinea capitis—scalp

Tinea barbae—beard

Tinea faciei—face

Tinea corporis—trunk and extremities

Tinea manuum—hands

Tinea cruris—groin

Tinea pedis—feet

Tinea unguium (onychomycosis)—nails

Three dermatophyte genera and 9 species are responsible for most infections in North America and Europe.

Trichophyton: rubrum, tonsurans, mentagrophytes, verrucosum, and schoenlenii

Microsporum: canis, audouinii, and gypseum

Epidermophyton: floccosum

The species within these genera may be further classified according to their host preferences:

Anthropophilic—human

Zoophilic—animal

Geophilic—soil

Infections can occur by direct contact with infected hosts or fomites.

Dermatophyte infections can mimic many common skin rashes. Therefore, it is important to confirm the diagnosis of a suspected fungal infection with a microscopic examination using KOH or with cultures.

Proper specimen collection is very important (Table 4-1). False-negative results can occur when specimens are taken from the wrong site or when insufficient volume is collected or when the patient has been using antifungal medications.

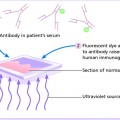

Most dermatophyte infections can be confirmed by performing a KOH examination (Table 4-1).

However, fungal cultures may be needed, especially in scalp and nail infections.

Cultures for dermatophytes are usually done on modified Sabouraud agar, such as dermatophyte test media (DTM) or MycoselTM or MycobioticTM. DTM contains an indicator dye that turns red within 7 to 14 days in the presence of dermatophytes. Identification of the specific species may be helpful in certain cases of tinea capitis and in the identification of zoophilic infections that may require treatment of the host animal. Specimens for culture can be placed in a sterile Petri dish or in a sterile urine cup and transported to the lab for placement on agar. If agar plates are available at the site of care, the specimens can be placed directly into the agar.

Tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) is a superficial dermatophyte infection of the hair shaft and scalp. It is most common in children 3 to 7 years old and it is uncommon after puberty. One study of 200 urban children showed a 4% overall incidence of asymptomatic colonization and a 12.7% incidence in African American girls.1 Tinea capitis is endemic in many developing countries, and can be associated with crowded living conditions.

Trichophyton tonsurans causes 90% of the cases in North America and in the United Kingdom.

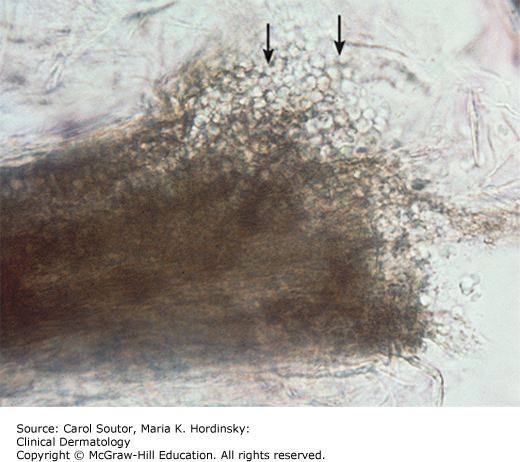

T. tonsurans fungal spores are confined within the hair shaft (endothrix) (Figure 10-1) and their presence can lead to hair breakage, creating “black dots” on the scalp. The spores are spread by person to person contact and by fomites such as combs, brushes, and pillows.

Microsporum canis is a more common pathogen in Europe, especially in the Mediterranean region.2 Its fungal spores are present primarily on the surface of the hair shaft (ectothrix). The spores are spread by contact with an infected animal, such as a dog or cat, or by contact with an infected person.

The clinical presentation depends on the pattern of tinea capitis. It may vary from mild pruritus, with flaking and no hair loss, to multiple scaly areas of alopecia, with erythema, pustules, or posterior cervical lymphadenopathy.

There are 6 patterns of tinea capitis:

Dandruff-like adherent scale, with no alopecia

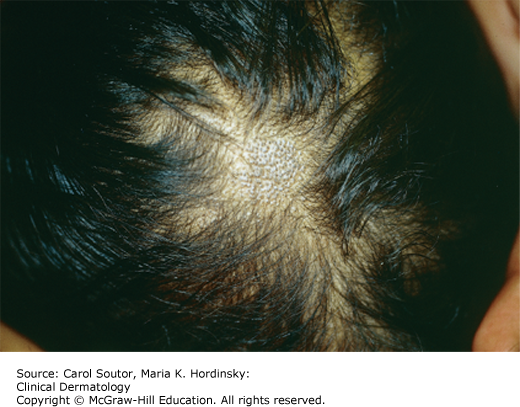

Areas of alopecia dotted with broken hair fibers that appear like black dots (Figure 10-2)

Circular patches of alopecia with marked gray scales. This is most commonly seen in Microsporum infections

“Moth-eaten” patches of alopecia with generalized scale

Alopecia with scattered pustules

Kerion, a boggy, thick, tender plaque with pustules (Figure 10-3) that is caused by a marked inflammatory response to the fungus. This is often misdiagnosed as a tumor or bacterial infection

Occipital lymphadenopathy is often present in tinea capitis. Green-blue fluorescence with Wood’s light is seen in Microsporum infections, due to the ectothrix nature of the dermatophyte. Wood’s light examination of tinea capitis caused by T. tonsurans is negative, because the fungal spores are within intact hair fibers.

KOH examination or cultures of the proximal hair fiber and scalp scales should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Table 4-1 lists some child-friendly techniques for specimen collection of scalp scales and techniques for collection of the proximal hair shaft.

KOH examination of the proximal hair fiber of T. tonsurans infections shows large spores within the hair shaft (endothrix) (Figure 10-1). Microsporum infections have smaller spores, primarily on the surface of the hair shaft (ectothrix). KOH evaluation of hair fiber specimens can be difficult, and interevaluator variability is common.

Use of DTM cultures is a nonspecific way of confirming dermatophyte infection. A color change in the media (from yellow to red) is usually noted within 2 weeks if a dermatophyte is present. However, this gives no information on the specific organism. Other agar-based cultures can take up to 4 to 6 weeks. Species identification can also be done if needed, especially if a pet animal is thought to be the source.

The key diagnostic clinical features of tinea capitis are patches of alopecia (with scale or black dots) or diffuse scaling with no alopecia. It occurs primarily in children and occipital lymphadenopathy is often present.

✓ Alopecia areata: Presents with alopecia, but there is no significant scale.

✓ Seborrheic dermatitis: Presents with mild pruritus, localized or diffuse scale on the scalp; typically there is no significant hair loss.

✓ Psoriasis: Presents with red, localized or diffuse silvery scaly plaques on the scalp. Similar plaques on the elbows and knees or elsewhere on the body are usually seen.

✓ Bacterial infections and tumors: These may closely resemble a kerion. However, tumors are rare in children and when they do occur, they should be biopsied to confirm the diagnosis.

✓ Other: Head lice, traction alopecia, trichotillomania, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Unlike other superficial fungal infections of the skin, tinea capitis does not respond to topical therapy alone. Systemic therapy is needed to penetrate the hair shaft and eradicate the infectious spores. Oral griseofulvin has been the gold standard of therapy for the past 45 years based on its cost and efficacy, and griseofulvin is the preferred antifungal medication for a kerion infection. It should be taken with a fatty meal or with whole milk or ice cream to improve absorption. Common side effects of griseofulvin include rash, headache, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Elevated liver function tests are rare. Table 10-1 contains the recommended pediatric dosage schedule for griseofulvin.

| Medication and Formulations | Pediatric Dosage | Duration |

|---|---|---|

Griseofulvin microsize (Grifulvin V) Available in 250 or 500 mg tablets or 125 mg/5 mL oral suspension | Package insert recommends 10-20 mg/kg/day, but 20-25 mg/kg/day in single or divided doses is more commonly used.3,4 Maximum dose is 1 g/day Dosage for children 2 years and younger has not been established | 4-8 weeks May need up to 12 weeks if not cleared |

Griseofulvin ultramicrosize (Gris-PEG) Available in 125 and 250 mg tablets | Package insert recommends approximately 5-10 mg/kg/day, but 10-15 mg/kg/day is more commonly used3,4 Maximum dose is 750 mg/day | 4 to 6 weeks Up to 12 weeks if not cleared |

Terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole are alternatives to griseofulvin5 (Table 10-2). These medications are more costly, may occasionally be hepatotoxic and have the potential for several drug interactions. However, the duration of treatment with these alternative medications is shorter and in some conditions, they are more effective. A recent meta-analysis suggested that terbinafine is more effective in Trichophyton infections, but griseofulvin is more effective in Microsporum infections.6 Baseline liver enzyme tests and a complete blood count are recommended in pediatric patients.

| Medications and Formulations | Pediatric Dose | Duration |

|---|---|---|

250 mg tablet | 62.5 mg daily for body weight of 10-20 kg 125 mg daily for body weight of 20-40 kg 250 mg daily for body weight greater than 40 kg | 2-4 weeks, up to 8 weeks for Microsporum infections |

Terbinafine (Lamisil) oral granules sprinkled into nonacid foods such as pudding 125 mg in a packet 187.5 mg in packet | 125 mg daily for body weight less than 25 kg 187.5 mg daily for body weight 25-35 kg 250 mg daily for body weight greater than 35 kg | 6 weeks |

100 mg capsule | Capsules: 5 mg/kg/daily | 2-6 weeks |

50, 100, 200 mg tablets or oral powder for suspension | 5-6 mg/kg/day | 3-6 weeks |

In addition, 2% ketoconazole (Nizoral) shampoo and 1% or 2.5% selenium sulfide (Selsun) shampoo should be used 2 to 3 times a week for 5 to 10 minutes during therapy to reduce surface fungal colony counts.

It is important to clean combs, brushes, and hats to prevent reinfection. Reinfection can also occur if household contacts or pets remain infected.

The use of oral steroids for a kerion infection remains controversial. However, if significant hair loss is noted, they should be considered, as the inflammation that occurs with a kerion can result in scarring alopecia.

Severe or persistent disease that does not respond to treatment.

PubMed Health: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001881/

Tinea corporis (ringworm) is a dermatophyte infection primarily of the skin of the trunk and limbs. It can occur at any age. Outbreaks are more frequent in day care facilities and schools. Epidemics can occur in wrestlers. It is more common in hot and humid areas, farming communities, and crowded living conditions.

Tinea corporis is caused most frequently by the anthromorphilic fungi, Trichophyton rubrum or Trichophyton mentagrophtes, or the zoophilic fungus, M. canis, which is spread by contact with cats and dogs and other mammals. These fungi can more easily infect inflamed or traumatized skin.

The patient usually complains of a mildly itchy, scaly papule that slowly expands to form a ring. Often there is history of another family member with a tinea infection.

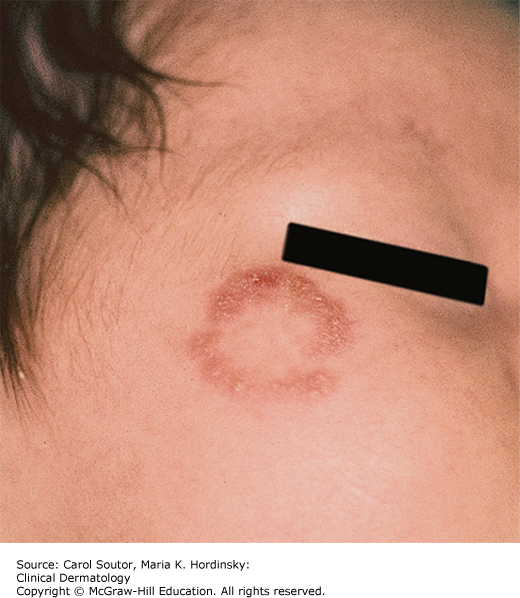

Tinea corporis presents initially as a red, scaly papule that spreads outward, eventually developing into an annular plaque with a scaly, slightly raised, well-demarcated border. The center of the lesion may partially clear resulting in a “ring” or “bull’s-eye” appearance (Figure 10-4).

Less common presentations include7:

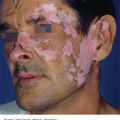

Tinea faciei: This is the term used for tinea infections that occur on the face, most often in children (Figure 10-5).

Majocchi granuloma: In rare instances, tinea corporis does not remain confined to the stratum corneum. Dermal invasion by hyphae following the hair follicle root can produce Majocchi granuloma, which presents as perifollicular granulomatous papules or pustules typically on the shins or arms.

Tinea incognito: This is an atypical presentation of tinea corporis that can occur when a dermatophyte infection has been treated with potent topical steroids or systemic steroids. It is characterized by dermal papules or kerion-like lesions with no inflammation, scaling, or pruritus.

KOH examination (Table 4-1) or cultures of scale from the active border of lesion(s) should be performed to confirm the diagnosis, as there are many diseases that present with red, scaly, annular skin lesions such as nummular dermatitis.

KOH examination of infected scale shows branched septate hyphae (Figure 4-1). DTM cultures are usually positive within 2 weeks. If indicated, a skin biopsy can be done to confirm the diagnosis. A periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain will show hyphae in the stratum corneum.

The key diagnostic clinical features of tinea corporis are annular, ring-like lesions with central clearing and a red, scaling border typically on the trunk or limbs.

✓ Nummular dermatitis: Presents with pruritic circular, coin-shaped, scaly plaques that have no central clearing.

✓ Atopic dermatitis: Presents with pruritic erythematous scaly plaques in patients with atopy.

✓ Tinea versicolor: Presents with multiple hyperpigmented or hypopigmented asymptomatic macular lesions with very fine powdery scales on the upper trunk with no central clearing. A KOH examination reveals both spores and hyphae.

✓ Granuloma annulare: Presents as skin-colored, smooth, dermal papules in a circular distribution that may coalesce into annular plaques. These plaques can vary from 1 to several centimeters and they typically occur on the dorsum of the hands and feet, and lower extremities. They usually spontaneously resolve over 1 to 2 years. The lack of scale is an important differentiating feature.

✓ Other: Candidiasis, psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, erythema multiforme, fixed drug eruption, subacute cutaneous lupus, secondary syphilis, and erythema migrans (Lyme disease).

Topical antifungal medications (Table 10-3) are effective for isolated lesions of tinea corporis.

| Medication | Nonprescription | Trade Name(s) Examples | Formulations | Dosing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allylamines | ||||

| Naftifine | No | Naftin | Cream, gel 1% | QD to BID |

| Terbinafine | Yes | Lamisil | Cream, spray 1% | BID |

| Imidazoles | ||||

| Clotrimazole | Yes | Lotrimin, Mycelex | Cream, lotion, solution 1% | BID |

| Econazole | No | Spectazole | Cream 1% | QD |

| Ketoconazole | No | Nizoral | Cream, shampoo 2% | BID |

| Miconazole | Yes | Micatin, Desenex, Monistat | Cream, ointment, lotion, spray Solution, powder 2% | BID |

| Oxiconazole | No | Oxistat | Cream, lotion 1% | QD to BID |

| Sertaconazole | No | Ertaczo | Cream 2% | BID |

| Sulconazole | No | Excelderm | Cream, solution 1% | QD to BID |

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| Butenafine | No | Mentax | Cream 1% | QD |

| Ciclopirox | No | Loprox | Cream, gel, solution 0.77% | BID |

| Tolnaftate | Yes | Tinactin | Cream, lotion, solution, spray, gel 1% | BID |

Topical antifungal medications should be applied at least 1 to 2 cm beyond the visible advancing edge of the lesions and treatment should be continued for 1 to 2 weeks after the lesions resolve. If the infection is extensive, or if it does not respond to topical therapy, oral griseofulvin can be used8 (Table 10-4).

| Medication and Formulations | Adult Dosing | Pediatric Dosing |

|---|---|---|

Microsized griseofulvin (Grifulvin V) Available in 250 and 500 mg tablets or 125 mg/5 mL oral suspension | 500 mg daily for 2-4 weeks | Approximately 125-250 mg/day for 2-4 weeks for body weight of 14-23 kg Approximately 250-500 mg/day for 2-4 weeks for body weight greater than 23 kg |

Ultramicrosized griseofulvin (Gris-Peg) Available in 125 and 250 mg tablets | 375 mg daily for 2-4 weeks | Approximately 125-187.5 mg/day for 2-4 weeks for body weight of 16-27 kg Approximately 187.5-375 mg/day for 2-4 weeks for body weight greater than 27 kg |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree