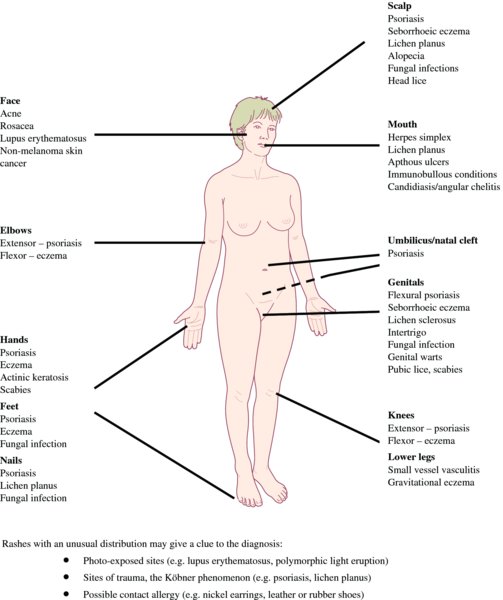

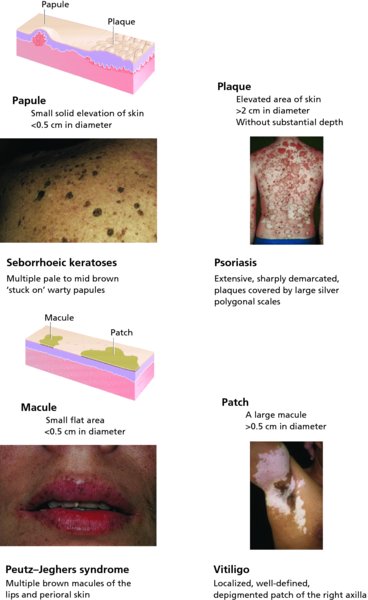

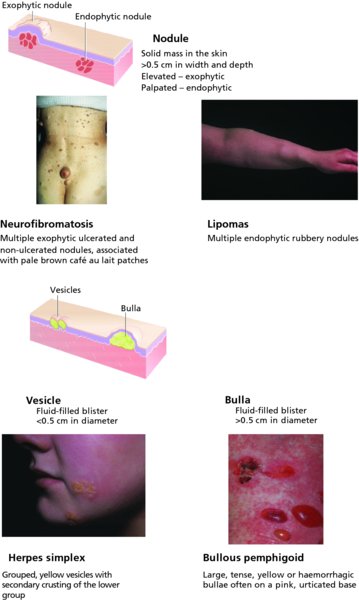

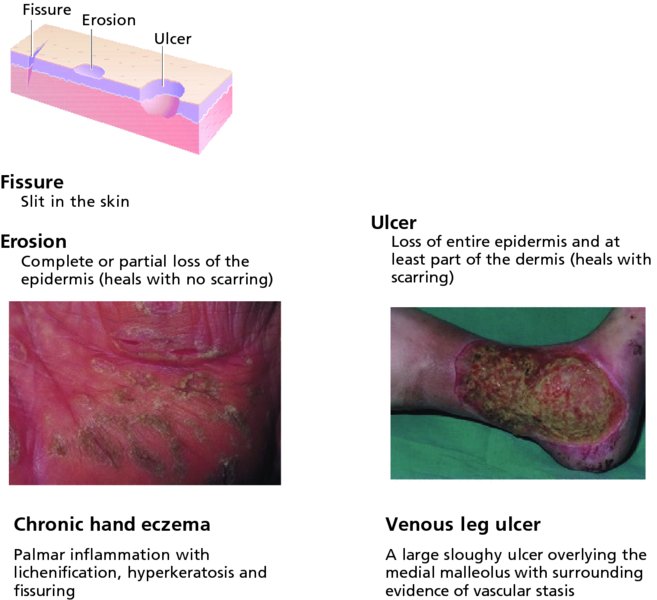

3 The key to successful treatment is an accurate diagnosis. You can look up treatments, but you cannot look up diagnoses. Without a proper diagnosis, you will be asking ‘What’s a good treatment for scaling feet?’ instead of ‘What’s good for tinea pedis?’ Would you ever ask yourself ‘What’s a good treatment for chest pain?’ Luckily, dermatology differs from other specialties as its diseases can easily be seen. Keen eyes and a magnifying glass are all that are needed for a complete examination of the skin. Sometimes it is best to examine the patient briefly before obtaining a full history: a quick look will often prompt the right questions. However, a careful history is important in every case, as is the intelligent use of the laboratory. The key points to be covered in the history are listed in Table 3.1 and should include descriptions of the events surrounding the onset of the skin lesions, of the progression of individual lesions and of the disease in general, including any responses to treatment. Many patients try a few salves before seeing a physician. Some try all the medications in their medicine cabinets, many of which can aggravate the problem. A careful enquiry into drugs taken for other conditions is often useful. Ask also about previous skin disorders, occupation, hobbies and disorders in the family. Table 3.1 Outline of dermatological history. To examine the skin properly, the lighting must be uniform and bright. Daylight is best. The patient should usually undress so that the whole skin can be examined, although sometimes this is neither desirable (e.g. hand warts) nor possible. Do not be put off this too easily by the elderly, the stubborn, the shy or the surroundings. The presence of a chaperone, ideally a nurse, is often sensible, and is essential if examination of the genitalia is necessary. Sometimes, make-up must be washed off or wigs removed. It is often important to remove adherent crust overlying the primary lesion to see and determine the underlying sign. There is nothing more embarrassing than missing the right diagnosis because an important sign has been hidden. A dermatological diagnosis is based both on the distribution of lesions and on their morphology and configuration. For example, an area of seborrhoeic dermatitis may look very like an area of atopic dermatitis; but the key to diagnosis lies in the location. Seborrhoeic dermatitis affects the scalp, forehead, eyebrows, nasolabial folds and central chest; atopic dermatitis typically affects the antecubital and popliteal fossae. Figure 3.1 shows the typical distribution of some common skin conditions. Figure 3.1 The typical distribution of some common skin conditions. See if the skin disease is localized, universal or symmetrical. Symmetry implies a systemic origin, whereas unilaterality or asymmetry implies an external cause. Depending on the disease suggested by the morphology, you may want to check special areas, like the feet in a patient with hand eczema, or the gluteal cleft in a patient who might have psoriasis. Examine as much of the skin as possible. Look in the mouth and remember to check the hair and the nails (see Chapter 13). Note negative as well as positive findings; for example, the way the shielded areas are spared in a photosensitive dermatitis (see Figure 18.7). Always keep your eyes open for incidental skin cancers which the patient may have ignored. After the distribution has been noted, next define the morphology of the primary lesions. Many skin diseases have a characteristic morphology, but scratching, ulceration and other events can change this. The rule is to find an early or ‘primary’ lesion and to inspect it closely. What is its shape? What is its size? What is its colour? What are its margins like? What are the surface characteristics? What does it feel like? Most types of primary lesion have one name if small, and a different one if large. The scheme is summarized in Table 3.2. Table 3.2 Terminology of primary lesions. There are many reasons why you should describe skin diseases properly. Figure 3.2 Terminology of skin lesions. The size in many of the definitions given below (e.g. papule, nodule, macule, patch) is arbitrary and it is often helpful to record the actual measurement. A papule is a small solid elevation of skin, less than 0.5 cm in diameter. A plaque is an elevated area of skin greater than 2 cm in diameter but without substantial depth. A macule is a small flat area, less than 0.5 cm in diameter, of altered colour or texture. A patch is a large macule. A vesicle is a circumscribed elevation of skin, less than 0.5 cm in diameter, and containing fluid. A bulla is a circumscribed elevation of skin over 0.5 cm in diameter and containing fluid. A pustule is a visible accumulation of pus in the skin. An abscess is a localized collection of pus in a cavity, more than 1 cm in diameter. Abscesses are usually nodules, and the term ‘purulent bulla’ is sometimes used to describe a pus-filled blister that is situated on top of the skin rather than within it. A furuncle or ‘boil’ is an infection of a single hair follicle and surrounding tissue. A carbuncle is an infection of a group of hair follicles and surrounding tissue. Folliculitis is inflammation of one or more hair follicles. A wheal is an elevated white compressible evanescent area produced by dermal oedema. It is often surrounded by a red axon-mediated flare. Although usually less than 2 cm in diameter, some wheals are huge. Angioedema is a diffuse swelling caused by oedema extending to the subcutaneous tissue. A nodule is a solid mass in the skin, usually greater than 0.5 cm in diameter, in both width and depth, which can be seen to be elevated (exophytic) or can be palpated (endophytic). A tumour is harder to define as the term is based more correctly on microscopic pathology than on clinical morphology. We keep it here as a convenient term to describe an enlargement of the tissues by normal or pathological material or cells that form a mass, usually more than 1 cm in diameter. Because the word ‘tumour’ can scare patients, tumours may courteously be called ‘large nodules’, especially if they are not malignant. A papilloma is a nipple-like projection from the skin. Petechiae are pinhead-sized macules of blood in the skin. The term purpura describes a larger macule or papule of blood in the skin. Such blood-filled lesions do not blanch if a glass lens is pushed against them (see below under Diascopy) An ecchymosis (bruise) is a larger extravasation of blood into the skin and deeper structures. A haematoma is a swelling from gross bleeding. A burrow is a linear or curvilinear papule, with some scaling, caused by a scabies mite. A comedo is a plug of greasy keratin wedged in a dilated pilosebaceous orifice. Open comedones are blackheads. The follicle opening of a closed comedo is nearly covered over by skin so that it looks like a pinhead-sized, ivory-coloured papule. Erythema is redness caused by vascular dilatation. Telangiectasia is the visible dilatation of small cutaneous blood vessels. Poikiloderma is a combination of atrophy, reticulate hyperpigmentation and telangiectasia. Horn is a keratin projection that is taller than it is broad. Erthyroderma is a generalized redness involving 90% or more of the skin, which may be scaling (exfoliative erythroderma) or smooth. These evolve from primary lesions. A scale is a flake arising from the horny layer. Scales may be seen on the surface of many primary lesions (e.g. macules, patches, nodules, plaques). A keratosis is a horn-like thickening of the stratum corneum. A crust may look like a scale, but is composed of dried blood or tissue fluid. An ulcer is an area of skin from which the whole of the epidermis and at least the upper part of the dermis has been lost. Ulcers may extend into subcutaneous fat, and heal with scarring. An erosion is an area of skin denuded by a complete or partial loss of only the epidermis. Erosions heal without scarring. An excoriation is an ulcer or erosion produced by scratching. A fissure is a slit in the skin. A sinus is a cavity or channel that permits the escape of pus or fluid. A scar is a result of healing, where normal structures are permanently replaced by fibrous tissue. Atrophy is a thinning of skin caused by diminution of the epidermis, dermis or subcutaneous fat. When the epidermis is atrophic it may crinkle like cigarette paper, appear thin and translucent, and lose normal surface markings. Blood vessels may be easy to see in both epidermal and dermal atrophy. Lichenification is an area of thickened skin with increased markings. A stria (stretch mark) is a streak-like linear atrophic pink, purple or white lesion of the skin caused by changes in the connective tissue. Pigmentation, either more (hyper) or less (hypo) than surrounding skin, can develop after lesions heal. Having identified the lesions as primary or secondary, adjectives can be used to describe them in terms of their other features.

Diagnosis of Skin Disorders

History

History of present skin condition

Duration

Site at onset, details of spread

Itch

Burning

Pain

Wet, dry, blisters, pustules

Exacerbating factors

Relationship of rash to work and holidays

Drugs used to treat present skin condition and clinical response

Topical

Systemic

Physician prescribed

Patient initiated

General health at present

Ask about fever, weight loss and night sweats

Past history of skin disorders

Past general medical history

Enquire specifically about asthma and hay fever (atopy)

Drugs prescribed for other disorders (including those taken before onset of skin disorder)

Any known drug allergies?

Family history of skin disorders

If positive, the disorder or the tendency to have it may be inherited. Sometimes, family members may be exposed to a common infectious agent or scabies or to a injurious chemical

Family history of other medical disorders

Social and occupational history

Alcohol intake

Smoking history

Hobbies

History of sun exposure:

Recent foreign travel

Examination

Distribution

Morphology

Small (<0.5 cm)

Large (>0.5 cm)

Elevated solid lesion

Papule

Nodule (>0.5 cm in both width and depth)

Plaque >2 cm in width but without substantial depth)

Flat area of altered colour or texture

Macule

Large macule (patch)

Fluid-filled blister

Vesicle

Bulla

Pus-filled lesion

Pustule

Abscess Furuncle/ carbuncle

Extravasation of blood into skin

Petechia (pinhead size)

Ecchymosis

Purpura (up to 2 mm in diameter)

Haematoma

Accumulation of dermal oedema

Wheal (can be any size)

Angioedema

Terminology of lesions (Figure 3.2)

Primary lesions

Secondary lesions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree