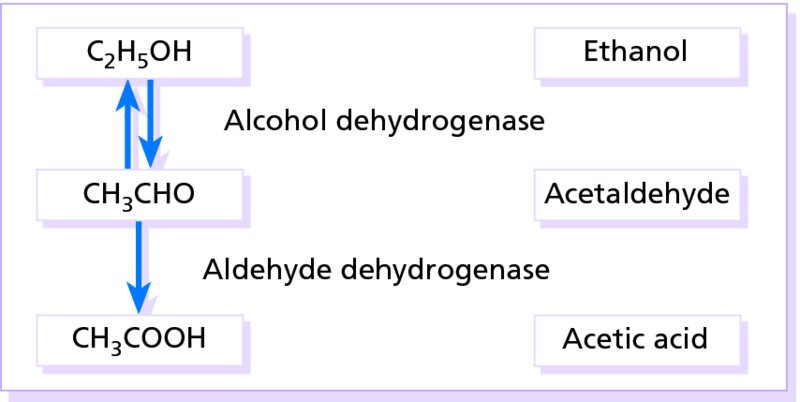

11 Disorders of blood vessels and lymphatics can be grouped into functional and structural diseases. In functional diseases, abnormalities of flow are reversible, and there is no vessel wall damage (e.g. in urticaria; discussed in Chapter 8). The diseases of structure include the many types of vasculitis, some of which, with an immunological basis, are also covered in Chapter 8. For convenience, disorders of the blood vessels are grouped according to the size and type of the vessels affected. This type of ‘poor circulation’, often familial, is more common in females than males. The hands, feet, nose, ears and cheeks become blue–red and cold. The palms are often cold and clammy. The condition is caused by arteriolar constriction and dilatation of the subpapillary venous plexus, and to cold-induced increases in blood viscosity. Patients have normal peripheral pulses, in contrast to those with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. The best answers are warm clothes and avoidance of cold. This occurs in fat, often young, women. Purple–red mottled discoloration is seen over the fatty areas such as the buttocks, thighs and lower legs. Cold provokes it and causes an unpleasant burning sensation. Most young people outgrow the condition, but an area of acrocyanosis or erythrocyanosis may be the site where other disorders will settle in the future (e.g. perniosis, erythema induratum, lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, cutaneous tuberculosis and leprosy). Weight reduction is often recommended. In this common, sometimes familial, condition, inflamed purple–pink swellings appear on the fingers, toes and, rarely, ears (Figure 11.1). They are painful, and itchy or burning on rewarming. Occasionally, they ulcerate. It tends to affect young to middle aged white women during winter, particularly on exposure to cold damp non-freezing temperatures. Chilblains are caused by a combination of arteriolar and venular constriction, the latter predominating on rewarming with exudation of fluid into the tissues. Lesions usually resolve in 1–3 weeks. Warm clothing and avoidance of precipitating conditions help. Topical remedies rarely work, but the oral calcium channel blocker nifedipine may be useful. The blood pressure should be monitored at the start of treatment and at return visits. The vasodilator nicotinamide (500 mg three times daily) may be helpful alone or in addition to calcium channel blockers. Sympathectomy may be advised in severe cases. Figure 11.1 The typical purplish swellings of chilblains. This is a rare paroxysmal condition in which the extremities (most commonly the feet) become red, hot, swollen and painful when exposed to heat, and relieved by cooling. The condition may be sporadic or familial. Secondary erythromelalgia is associated with a myeloproliferative disease (e.g. polycythaemia rubra vera or thrombocythaemia), lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, degenerative peripheral vascular disease or hypertension. Elevation and cooling of the extremities can be helpful. Small doses of aspirin give symptomatic relief. Topical therapies include capsaicin cream and lidocaine patch. Alternatives include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), gabapentin, beta-blockers, pentoxifylline and the serotonin re-uptake inhibitor venlafaxine. Erythema accompanies all inflammatory skin conditions, but the term ‘the erythemas’ is usually applied to a group of conditions with redness but without primary scaling. Such areas are seen in some bacterial and viral infections such as toxic shock syndrome and measles. Drugs are another common cause (see Chapter 25). If no cause is obvious, the rash is often called a ‘toxic’ or ‘reactive’ erythema. When erythema is associated with oedema (urticated erythema) it becomes palpable. These are chronic eruptions, made up of bizarre serpiginous and erythematous rings. In the past most carried Latin labels; happily, these eruptions are now grouped under the general term of figurate erythemas. Underlying malignancy, a connective tissue disorder, a bacterial, viral, fungal or yeast infection, parasitic and worm infestation, drug sensitivity and rheumatic heart disease should be excluded, but often the cause remains obscure. This may be an isolated finding in a normal person or be familial. It occurs in at least 30% of pregnant women. It can be associated with liver disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Often associated with spider telangiectases (see Telangiectases), it may be caused by increased circulating oestrogens. This term refers to permanently dilated and visible small vessels in the skin. They appear as linear, punctate or stellate crimson–purple markings. They can occur as a primary process or secondary to an underlying systemic disease or physical damage to the skin. The common causes are given in Table 11.1. Table 11.1 Causes of telangiectasia. These stellate telangiectases do look rather like spiders, with legs radiating from a central, often palpable, feeding vessel. If the diagnosis is in doubt, press on the central feeding vessel with the corner of a glass slide and the entire lesion will disappear. Spider naevi are seen frequently on the faces of normal children, and may erupt in pregnancy or be the presenting sign of liver disease, with many lesions on the upper trunk. Liver function should be checked in those with many spider naevi. The central vessel can be destroyed by electrodessication without local anaesthesia or with a vascular laser (p. 380). This cyanosis of the skin is net-like (reticulated) or marbled and caused by stasis in the capillaries furthest from their arterial supply: at the periphery of the inverted cone supplied by a dermal arteriole (see Figure 2.1). It may be widespread or localized. Cutis marmorata is the name given to the mottling of the skin seen in many normal children. It is a physiologic vasospastic response to cold exposure and disappears on warming, whereas true livedo reticularis remains. The causes of livedo reticularis are listed in Table 11.2. Livedo vasculitis and cutaneous polyarteritis are forms of vasculitis associated with livedo reticularis (see Chapter 8). Localized forms suggest localized blood vessel injury, for example from cholesterol emboli. Table 11.2 Common causes of livedo reticularis. Some patients with an apparently idiopathic livedo reticularis develop progressive disease in their peripheral, cerebral, coronary and renal arteries. Others, usually women, have multiple arterial or venous thrombo-embolic episodes accompanying livedo reticularis. Recurrent spontaneous abortions and intrauterine fetal growth retardation are also features. Prolongation of the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (either anticardiolipin antibody or lupus anticoagulant, or both) help to identify this syndrome. Systemic lupus erythematosus should be excluded (p. 126). This appearance is also determined by the underlying vascular network. Its brownish pigmented, reticulated erythema, with variable scaling, is caused by damage from long-term exposure to local heat or infrared source – usually from an open fire, hot water bottle, heating pad or, in recent years, laptop computer. If on one side of the leg, it gives a clue to the side of the fire on which granny likes to sit (Figure 11.2). The condition has become less common with the advent of central heating. Figure 11.2 Erythema ab igne: this patient persisted in sitting too close to an open fire and burned herself. This transient vasodilatation of the face may spread to the neck, upper chest and, more rarely, other parts of the body. There is no sharp distinction between flushing and blushing apart from the emotional provocation of the latter. The mechanism varies with the many causes that are listed in Table 11.3. Paroxysmal flushing (‘hot flushes’), common at the menopause, is associated with the pulsatile release of luteinizing hormone from the pituitary, as a consequence of low circulating oestrogens and failure of normal negative feedback. However, luteinizing hormone itself cannot be responsible for flushing as this can occur after hypophysectomy. It is possible that menopausal flushing is mediated by central mechanisms involving encephalins. Hot flushes can usually be helped by oestrogen replacement, clonidine or serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Table 11.3 Causes of flushing. Alcohol-induced flushing is caused by the vasodilatory effects of alcohol and accumulation of acetaldehyde. Ethanol is broken down to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase and acetaldehyde is metabolized to acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase (Figure 11.3). This condition is most prevalent in Japanese, Chinese and Koreans, as they have a high-activity variant of alcohol dehydrogenase and defective aldehyde dehydrogenase. Disulfiram (Antabuse) and, to a lesser extent, chlorpropamide inhibit aldehyde dehydrogenase so that some individuals taking these drugs may flush. Figure 11.3 The metabolism of ethanol. This is a common paroxysmal vasospasm of the digital arteries provoked by cold or, rarely, emotional stress. The result is a characteristic progression of white, blue and red discoloration of the fingers. At first, the top of one or more fingers becomes white due to vasoconstriction. A painful cyanosis then appears as the residual blood in the finger desaturates. On rewarming, the rapid reperfusion of the digit turns the area red before the hands return to their normal colour. Raynaud’s disease, often familial and typically affecting adolescent women, is the name given when no cause can be found. In contrast, secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon affects women over age 25 and is associated with an underlying systemic disease, usually scleroderma. The presence of other signs of connective tissue disease, including prominent dilated nailfold capillaries (see Figure 10.7), sclerodactyly and positive autoantibodies, can distinguish secondary from primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. In severe cases of secondary Raynaud’s, the fingers lose pulp substance, ulcerate or become gangrenous (Figure 11.4). Some causes are listed in Table 11.4. Table 11.4 Causes of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Figure 11.4 Digital gangrene. In this case caused by frostbite. The main treatment is to protect the vulnerable digits from cold. Warm clothing reduces the need for peripheral vasoconstriction to conserve heat. Smoking should be abandoned. Second-line therapy is with vasodilators, the most effective being calcium channel blockers (e.g. nifedipine 10–30 mg three times daily) for patients with primary Raynaud’s disease. Patients should be warned about dizziness caused by postural hypotension. Initially, it is worth giving nifedipine as a 5-mg test dose with monitoring of the blood pressure in the clinic. If this is tolerated satisfactorily the starting dosage should be 5 mg/day, increasing by 5 mg every 5 days until a therapeutic dose is achieved (e.g. 5–20 mg three times daily) or until intolerable side effects occur. The blood pressure should be monitored before each incremental increase in the dosage. Diltiazem (30–60 mg three times daily) is less effective than nifedipine but has fewer side effects. The systemic vasodilator inositol nicotinate may help, and a combination of low dose acetylsalicylic acid and the antiplatelet drug dipyridamole is also worth trying. Sustained release glycerol trinitrate patches, applied once daily, may reduce the severity and frequency of attacks and allow reduction in the dosage of calcium channel blockers and vasodilatators. Slow intravenous infusions with prostaglandin analogues, which are potent vasodilators and inhibitors of platelet aggregation, help some severe cases. Endothelin receptor antagonists (bosentan) and phosphodiesterase inhibitors (sildenafil) have also been used with varying success. This is discussed in Chapter 8, p. 110. This condition, also termed giant cell arteritis, is a vasculitis of the large and middle-sized blood vessels of the head and neck. It affects elderly people and may be associated with polymyalgia rheumatica. The classic site is the temporal arteries, which become tender and pulseless, in association with severe headaches, jaw claudication and constitutional symptoms (malaise, fever, weight loss). Rarely, necrotic ulcers appear on the scalp. Blindness may follow if the ophthalmic arteries are involved and, to reduce this risk, systemic steroids should be given as soon as the diagnosis has been made. A temporal artery biopsy is the gold standard test for diagnosis. In active phases the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is high and its level can be used to guide treatment, which is often prolonged. This occlusive disease, most common in developed countries, is not discussed in detail here, but involvement of the large arteries of the legs is of concern to dermatologists. It may cause intermittent claudication, nocturnal cramps, ulcers or gangrene. These may develop slowly over the years or within minutes if a thrombus forms on an atheromatous plaque. The feet are cold and pale, the skin is often atrophic, with little hair, and peripheral pulses are diminished or absent. Investigations should include urine testing to exclude diabetes mellitus. Fasting plasma lipids (cholesterol, triglycerides and lipoproteins) should be checked in the young, especially if there is a family history of vascular disease. Doppler ultrasound measurements help to distinguish atherosclerotic from venous leg ulcers in the elderly (see Venous hypertension: investigations). Complete assessment is best carried out by a specialist in peripheral vascular disease or a vascular surgeon.

Disorders of Blood Vessels and Lymphatics

Disorders involving small blood vessels

Acrocyanosis

Erythrocyanosis

Perniosis (chilblains)

Erythromelalgia

Erythemas

Figurate erythemas

Palmar erythema

Telangiectases

Primary telangiectasia

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia

Autosomal dominant

Nose and gastointestinal bleeds

Lesions on face, lips, and hands

Variable involvement of the lungs, liver and CNS

Ataxia telangiectasia

Autosomal recessive

Telangiectases develop between the ages of 3 and 5 years

Cerebellar ataxia

Recurrent respiratory infections

Immunological abnormalities

Generalized essential telangiectasia

Typically affects adult women, may commence in childhood

Multiple lesions on legs

Runs benign course

No other associations

Unilateral naevoid telangiectasia

Unilateral distribution of telangiectases

May occur in pregnancy or in females on oral contraceptive

Secondary telangiectasia

Rosacea

Associated with centrofacial erythema (erythematotelangiectatic subtype)

Sun-damaged skin

Atrophy

Seen on exposed skin of elderly, after topical steroid applications, after radiation therapy, and with poikiloderma

Connective tissue disorders

Always worth inspecting nail folds

Mat-like on the face in systemic sclerosis

Prolonged vasodilatation

For example, with venous hypertension

Mastocytosis

Accompanying a rare and diffuse variant

Liver disease

Multiple spider telangiectases are common

Drugs

Nifedipine

Tumours

A tell-tale sign in nodular basal cell carcinomas

Spider naevi

Livedo reticularis

Physiological

Cutis marmorata/ physiologic livedo reticularis

Vessel wall disease

Atherosclerosis

Connective tissue disorders (especially polyarteritis, livedo vasculitis and systemic lupus erythematosus)

Vessel obstruction

Embolic (cholesterol, septic emboli) Calciphylaxis

Hyperviscosity states

Polycythaemia/thrombocythaemia Macroglobulinaemia

Cryopathies

Cryoglobulinaemia

Cold agglutininaemia

Cryofibrinogenaemia

Hypercoagulability

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Sneddon’s syndrome

Medications

Amantadine, minocycline, quinidine, catecholamines

Congenital

Idiopathic

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Erythema ab igne

Flushing

Physiological

Emotional (blushing)

Menopausal (‘hot flushes’)

Exercise

Foods

Hot drinks

Spicy foods

Additives (monosodium glutamate)

Alcohol (especially in Oriental people)

Drugs

Vasodilatators including nicotinic acid, hydralazine

Nitrates and sildenafil

Calcium channel blockers including nifedipine

Disulfiram or chlorpropamide + alcohol

Cholinergic agents

Pathological

Mastocytosis

Carcinoid tumours – with asthma and diarrhoea

Phaeochromocytoma (type producing adrenaline) – with episodic headaches (caused by transient hypertension) and palpitations

Dumping syndrome

Migraine headaches

Arterial disease

Raynaud’s phenomenon

Familial

Raynaud’s disease (idiopathic)

Connective tissue diseases

Systemic sclerosis

Lupus erythematosus

Dermatomyositis

Mixed connective tissue disease

Arterial occlusion

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Atherosclerosis

Endarteritis obliterans (Buerger disease)

Repeated trauma

Pneumatic hammer/drill operators (‘vibration white finger’)

Hyperviscosity

Polycythaemia

Macroglobulinaemia

Cryopathies

Cryoglobulinaemia

Cryofibrinogenaemia

Cold agglutinaemia

Neurological disease

Peripheral neuropathy

Syringomyelia

Toxins

Ergot

Vinyl-chloride

Polyarteritis nodosa

Temporal arteritis

Atherosclerosis

Arterial emboli

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree