Skin Changes and Diseases in Pregnancy: Introduction

|

Changes Commonly Associated with Pregnancy

Pregnancy is characterized by altered endocrine, metabolic, and immunologic milieus. These dramatic alterations result in multiple cutaneous changes, both physiologic and pathologic. A comprehensive list of physiologic alterations within the skin and appendages is provided in Table 108-1.1–3

Pigmentary

|

Hair

|

Nail

|

Glandular

|

Structural Changes

|

Vascular

|

Mucosa

|

Pigmentary disturbances are the most common of these physiologic changes (see Table 108-1). Hyperpigmentation of the areola, axillae, and genitalia is well documented in pregnancy. Linea nigra refers to the typically reversible darkening of the linea alba, a hypopigmented linear patch extending from the pubis symphysis to the xiphoid process of the sternum (Fig. 108-2). Melasma or chloasma is a related finding comprising irregular, blotchy, facial hyperpigmentation that occurs in up to 70% of pregnant women (see eFig. 108-2.1). This tendency is aggravated by sun exposure and by oral contraceptive intake by nonpregnant women. Melasma may regress postpartum, but oftentimes persists, posing a therapeutic challenge.1

Figure 108-1

Spider angiomata on the arm of a pregnant woman. These spider nevi, as they are also called, have a central “body” and small vessels (legs) extending out from it. In this example, they are part of a unilateral nevoid telangiectasia, linear grouping of spider angiomata that can become more prominent during pregnancy.

Changes in melanocytic nevi were historically deemed “normal” during pregnancy. However, few studies have objectively studied whether and how nevi evolve during pregnancy. Pennoyer et al4 photographically monitored 129 melanocytic nevi throughout the pregnancies of 22 healthy Caucasian women. Only eight nevi (6.2%) changed in diameter from the first to third trimester, with a mean change in size of zero. The authors concluded that significant change in nevus size (excluding nevi on the pregnant abdomen) does not appear to be a feature of most pregnancies.4 Until further controlled studies are performed, any pigmented lesion in a pregnant woman that undergoes change in morphology (size, color, or shape) or symptomatology (begins to itch, bleed, or scale) should be considered for histopathologic review. Recently, Chan et al identified characteristic histologic features unique to nevi excised during pregnancy, including increased mitotic index.5

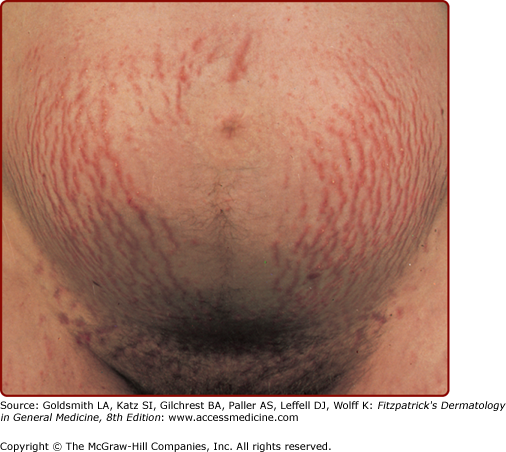

The most common structural change during pregnancy is striae distensae, also known as striae gravidarum or stretch marks (Fig. 108-3). Sites of predilection for striae include those areas most prone to stretch, including the abdomen, hips, buttocks, and breasts. Genetic factors as family history, personal history, and race are the strongest predictors of an individual’s risk of developing striae distensae, surpassing pregnancy weight gain or changes in body mass index.6 These findings strongly support a genetic predisposition to this condition.

Pruritus, a common complaint during pregnancy, may be physiologic, but may herald a flare of a preexisting dermatosis or onset of a specific dermatosis of pregnancy. The remainder of this chapter outlines the relatively rare conditions that may be specific to pregnancy. An overview of these conditions is provided in Table 108-2.

Morphology | Distribution | Usual Onset | Fetal Risk | Synonym(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis | Urticarial papules and plaques progress to vesicles and bullae | Begins on trunk, then progresses to generalized eruption Spares face, mucus membranes, palms, soles | Second or third trimester, or immediately postpartum | Small-for-gestational age births Preterm delivery Neonatal pemphigoid gestationis | Herpes gestationis |

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | Excoriations and excoriated papules ± jaundice | Localized to palms and soles or generalized | Third trimester | Preterm delivery Fetal distress Fetal death | Cholestasis of pregnancy Obstetric cholestasis Recurrent jaundice of pregnancy Cholestatic jaundice of pregnancy Idiopathic jaundice of pregnancy Prurigo gravidarum Icterus gravidarum |

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy | Erythematous patches with subcorneal pustules at their margins | Begins in flexures Generalizes demonstrating centrifugal spread | Third trimester | Placental insufficiency may lead to stillbirth or neonatal death | Impetigo herpetiformis |

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy | “Polymorphous” including urticarial papules and plaques ± vesicles | Begins within abdominal striae Spreads to remainder of trunk and then extremities Spares umbilicus | Third trimester or immediately postpartum | None | Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy Bourne’s toxemic rash of pregnancy Nurse’s late onset prurigo of pregnancy Toxemic erythema of pregnancy (Holmes) |

E-type Atopic eruption of pregnancy | Eczematous patches and plaques | Face, neck, chest, flexural extremities | Second or third (less commonly) trimester | None | Eczema in pregnancya |

P-type Atopic eruption of pregnancy | Excoriated or crusted papules | Extremities, occasionally trunk | Second or third (less commonly) trimester | None | Prurigo of pregnancya Besnier’s prurigo gestationis Nurse’s early onset prurigo of pregnancy Papular dermatitis of Spangler Atopic eruption of pregnancya |

Dermatoses Associated with Fetal Risk in Pregnancy

|

Pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis (PG; see Chapter 59) is an intensely pruritic, vesiculobullous eruption of mid- to late pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period. PG classically begins during the second or third trimester, and is manifest by the abrupt appearance of severely pruritic urticarial lesions on a background of normal or erythematous skin. PG is associated with an increased incidence of small-for-gestational age births and premature delivery. PG is immunologically mediated, and linear deposition of C3 with or without IgG are found at the dermal–epidermal junction by direct immunofluorescence (DIF).7

The terms obstetric cholestasis, cholestasis of pregnancy, recurrent jaundice of pregnancy, cholestatic jaundice of pregnancy, idiopathic jaundice of pregnancy, prurigo gravidarum, and icterus gravidarum all refer to the same clinical entity, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), characterized by a reversible form of cholestasis in late pregnancy. Svanborg and Ohlsson first recognized ICP as a distinct entity, separate from other causes of jaundice during pregnancy in 1939.8 Jaundice develops in approximately 1 in 1,500 pregnant women. With an estimated incidence of 70 cases per 10,000 pregnancies in the United States, ICP ranks second only to viral hepatitis in terms of etiology of jaundice in pregnant women.9 Mild cases of ICP, in which pruritus is not accompanied by jaundice, were previously referred to as prurigo gravidarum.

ICP is most common in Scandinavia and South America. The highest reported incidence rates are in Chile (14%–16%), whereas much lower rates are seen among pregnant women in the United States (less than 0.1%–0.7%), Canada (0.1%), Australia (0.2%–1.5%), and Central Europe (0.1%–1.5%).9

Although the precise pathogenesis remains unclear, the interplay of hormonal, genetic, environmental, and alimentary factors is thought to induce a biochemical cholestasis in susceptible individuals. A prominent role for hormonal alterations is suggested by the following observations: (1) ICP is a disease of late pregnancy (corresponding to the period of highest placental hormone levels); (2) ICP spontaneously remits at delivery when hormone concentrations normalize; (3) twin and triplet pregnancies, characterized by greater rises in hormone concentrations, have been linked to ICP; and, (4) ICP recurs during subsequent pregnancies in an estimated 45%–70% of patients.9,10

Geographic variation and familial clustering indicate a genetic predisposition. ICP appears to be a polygenetic condition. Candidate genes include those mutated in a variety of other forms of inherited cholestasis: ABCB4 (multidrug resistance gene3), ABCB11 (Bsep), and ATP8B1 (FIC1). A recent decline in prevalence rates in Chile, reports of higher incidence rates during the winter months, and reports of relative reductions of selenium levels in some ICP patients all point toward etiologic roles for environmental and alimentary factors.9,11 At least one study confirmed a higher risk of hepatitis C virus infection among women with ICP.12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree