Skin Cancer

Fareesa Shuja

Zena W. Zoghbi

Over 2 million new cases of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) were diagnosed in 2012 in the United States. This number is greater than the annual number of all other newly diagnosed cancers combined. The etiologies of skin cancer include exogenous and endogenous factors that interact to lead to carcinogenesis. Endogenous factors include (i) skin type, (ii) immunosuppression (leukemia, HIV infection, etc.), and (iii) genetic predisposition (family history, basal cell nevus syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosum, etc.). The most important exogenous factor is ultraviolet radiation which promotes immunosuppression, damages chromosomes, and generates reactive oxygen species. Other exogenous factors include (i) ionizing radiation, (ii) chemical carcinogens (arsenic), (iii) human papillomavirus (HPV), and (iv) chronic irritation (ulcers and burns).

BASAL CELL CARCINOMA

I. BACKGROUND

Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) arise from a pluripotential cell in the basal layer of the epidermis. They make up 75% of all skin cancers.1 One in every five Americans will develop an NMSC, and 95% of these will be a BCC. They are more common in men and tend to grow very slowly with an extremely low rate of metastasis (0.0028% to 0.55%).2 About 80% of BCCs and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) occur on the head and neck.1 Individuals with an NMSC have a 10-fold increased risk for developing a second NMSC, with more than 40% developing a BCC within 3 years.2

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A. Nodular BCC. This subtype of BCC has rolled, easily defined borders (Fig. 40-1). The surface has a slightly translucent or pearly quality, often with central crust or ulceration and surface telangiectasias. Nodular BCCs make up 50% to 80% of all BCCs;2 85% to 90% are found on the head and neck.

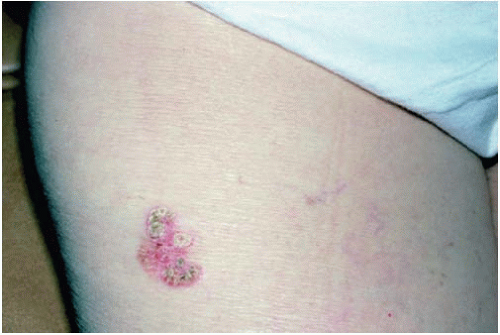

B. Superficial BCC. Superficial BCCs appear as erythematous scaly plaques with irregular, elevated, well-demarcated borders and variable telangiectasias (Fig. 40-2). They are commonly found on the trunk and extremities.2

III. WORKUP

All suspected skin cancers should be biopsied to confirm the diagnosis and to determine the necessary treatment. Most BCCs can be biopsied with a tangential shave technique. Larger lesions may require an incisional or excisional biopsy.

IV. TREATMENT

The age and health of the patient, size and location of the tumor, and pathology must be considered when planning therapy. Follow-up for NMSC should be on a 6- to 12-month basis.

A. Standard Excisional Surgery with 4-mm margins is curative in 98% of non-morpheaform BCCs that are <2 cm in size.1

B. Electrodesiccation and Curettage should be reserved for superficial tumors on non-facial areas. In this technique, the tumor is removed by curettage, and the site is then electrodesiccated with a 1- to 2-mm margin of normal skin. This process is then repeated for a total of three times. Cure rates approach 87% in experienced hands.

C. Cryotherapy by spray technique is also inferior to standard excision and should also be reserved for smaller superficial lesions. After injecting local anesthesia, two cycles of a 30-second full freeze with a thaw time of at least 90 seconds should be performed. The site will swell, become painful, and blister over 1 to 2 days. Permanent hypopigmentation is a common side effect.

D. Mohs Micrographic Surgery is an excisional surgical technique in which 100% of the margins are examined to determine whether residual tumor is present at the time of surgery. This tissue-sparing technique provides the highest possible cure rate for contiguous tumors such as BCCs and SCCs. Indications for Mohs surgery are sites requiring tissue preservation, highrisk locations, immunosuppression, aggressive pathology, tumors >2 cm, recurrent tumors, and poorly defined tumors. Cure rates for primary BCC are 98% to 99%.1

E. 5-Fluorouracil is a topical therapy for superficial, small BCCs. It is applied twice a day for 4 to 6 weeks. For nodular BCCs, topical treatment is effective only 65% of the time.2

F. Topical Imiquimod 5% cream is an immune response modifier that is indicated for the treatment of primary superficial BCCs that are less than 2 cm in diameter on low-risk areas. It is applied 5 times per week for at least 6 weeks with an 80% cure rate for superficial BCCs.2

G. Ionizing Radiation is usually reserved for individuals who are poor surgical candidates.

H. Vismodegib, an orally bioavailable inhibitor of Hedgehog signaling, was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic BCCs that are inoperable.3

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

I. BACKGROUND

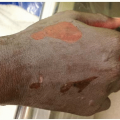

SCCs arise from epidermal keratinocytes, usually in the setting of moderate-to-severe actinic damage. SCCs make up 25% of all skin cancers.1 In dark-skinned patients, SCCs are 20% more common than BCCs.2 They tend to grow more rapidly than BCCs and may extend along nerves with a metastatic potential of 0.5% to 5.2%.2 Lesions on the ear, lip, penis, and dorsum of the hand have a higher metastatic rate; for instance, SCCs on the lower lip metastasize 10% to 15% of the time. In solid organ transplant patients, there is a 65-fold increase in the incidence of SCC.4 SCCs behave more aggressively in this group and have a higher rate of metastasis.

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

An SCC typically presents as an enlarging, scaling, dome-shaped nodule that often arises from an actinic keratosis (AK). An AK is a rough scaly papule that develops on sun-exposed areas. The rate of each AK developing into an SCC is 0.075% to 0.096% per lesion per year.1 Some variants of SCCs are discussed below.

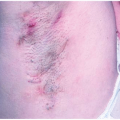

A. SCC In Situ aka Bowen disease appears as a well-demarcated, scaling plaque (Fig. 40-4).

B. Bowenoid Papulosis appears as multiple slightly verrucous papules on the genitalia. They are induced by HPV type 16 or 18 and, while considered premalignant, they are often indolent.1

C. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is Bowen disease on the glans penis and typically presents as a well-demarcated red plaque.

D. A Keratoacanthoma is a rapidly growing, well-demarcated nodule with a cup-shaped center filled with keratinous material (Fig. 40-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree