Alopecia Areata

Paul M. Hoesly

Murad Alam

I. BACKGROUND

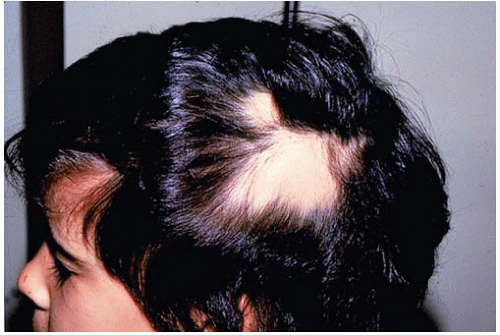

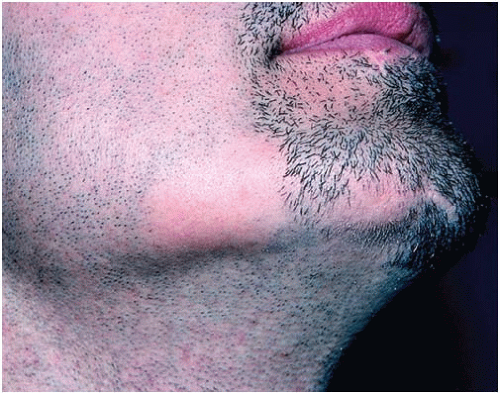

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune disease of the hair follicle. The prevalence in the United States is 0.1% to 0.2%, with a lifetime risk of 1.7%. AA is characterized by rapid and often complete hair loss in one or more patches of skin. It most commonly affects the scalp (90% of cases), but may also involve the eyebrows, eyelashes, face, and other hair-bearing parts of the body (Figs. 2-1 and 2-2). The hair loss is non-scarring, and spontaneous remission occurs in 34% to 50% of patients within 1 year of disease onset.1 While the exact etiology of AA remains unknown, evidence suggests that there is a T lymphocyte-mediated autoimmune reaction with antigens selectively expressed in the hair follicle. Environmental triggers have also been implicated in the pathogenesis.

AA appears to have a familial incidence of 10% to 30% and is highly associated with other disease processes. The most common of these comorbidities are autoimmune diseases, such as vitiligo, thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, and rheumatoid arthritis, and atopic diseases, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis. There is also a significant association with Trisomy 21.

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

AA most commonly affects the pediatric and young adult populations, but can occur at any age and has equal gender distribution. In most cases, there is rapid loss of hair in one or a few well-demarcated patches on the scalp. This is called patchy AA, which comprises 75% of cases. Active lesions are generally round or oval and are 1 to 5 cm in diameter with expanding margins characterized by “exclamation point” hairs—so called because the distal end of the hair shaft is of greater diameter than the proximal end. The skin at lesion sites usually shows no overt abnormalities, and there is complete preservation of the follicular ostia. Occasionally, lesions will show mild erythema and may be associated with pruritus and dysesthesia. However, the vast majority of cases are asymptomatic. In patients with lesions showing spontaneous remission, initial hair regrowth may appear as very fine vellus strands, which are often white. In approximately 10% of cases, patients will also develop uniform pitting of the nails in longitudinal or horizontal lines. Other acute nail involvement such as trachyonychia, periungual erythema, and red-spotted lunula may occur, but these are rare.

Aside from the more common patchy variant, AA may present as five other pattern subtypes:

Alopecia Reticularis: Multiple lesions that may be either active, stable, or recovering simultaneously. A mosaic pattern is often observed.

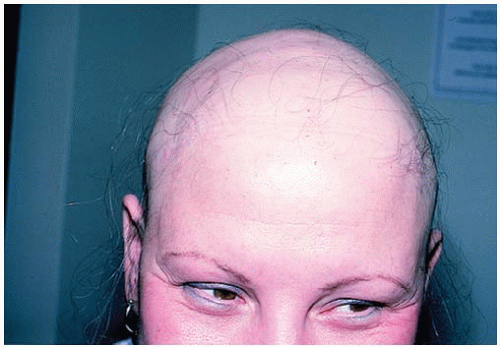

Alopecia Totalis (AT; 10% to 20%): Complete loss of scalp hair.

Alopecia Universalis (AU): Complete loss of scalp and body hair (Fig. 2-3).

Diffuse AA: Hair loss occurring in equal distribution throughout the scalp without the formation of discrete patches.

Ophiasis: Band of hair loss along the occipital hairline that extends to the temples.

III. WORKUP

The diagnosis of AA can usually be made based solely upon patient history and clinical presentation. In cases of uncertainty, dermoscopy may be useful, which will reveal yellow dots indicating keratotic plugs within follicular ostia. If the diagnosis is still in question, a biopsy may be required

to rule out pathology that may mimic AA (Table 2-1). Histology will show peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate (“swarm of bees”).

to rule out pathology that may mimic AA (Table 2-1). Histology will show peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate (“swarm of bees”).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|